In the course of seven years, cinema’s most persevering director Paul Schrader has pieced together an informal trilogy of films that have both administered brutal last rites to a planet killing itself, and restored his own reputation. He’s tackled pollution (First Reformed), war (The Card Counter), and homegrown hatred (Master Gardener), but for the moment, Schrader has put the apocalypse on hold, shifting his attention from macro-destruction to the micro- with his latest film.

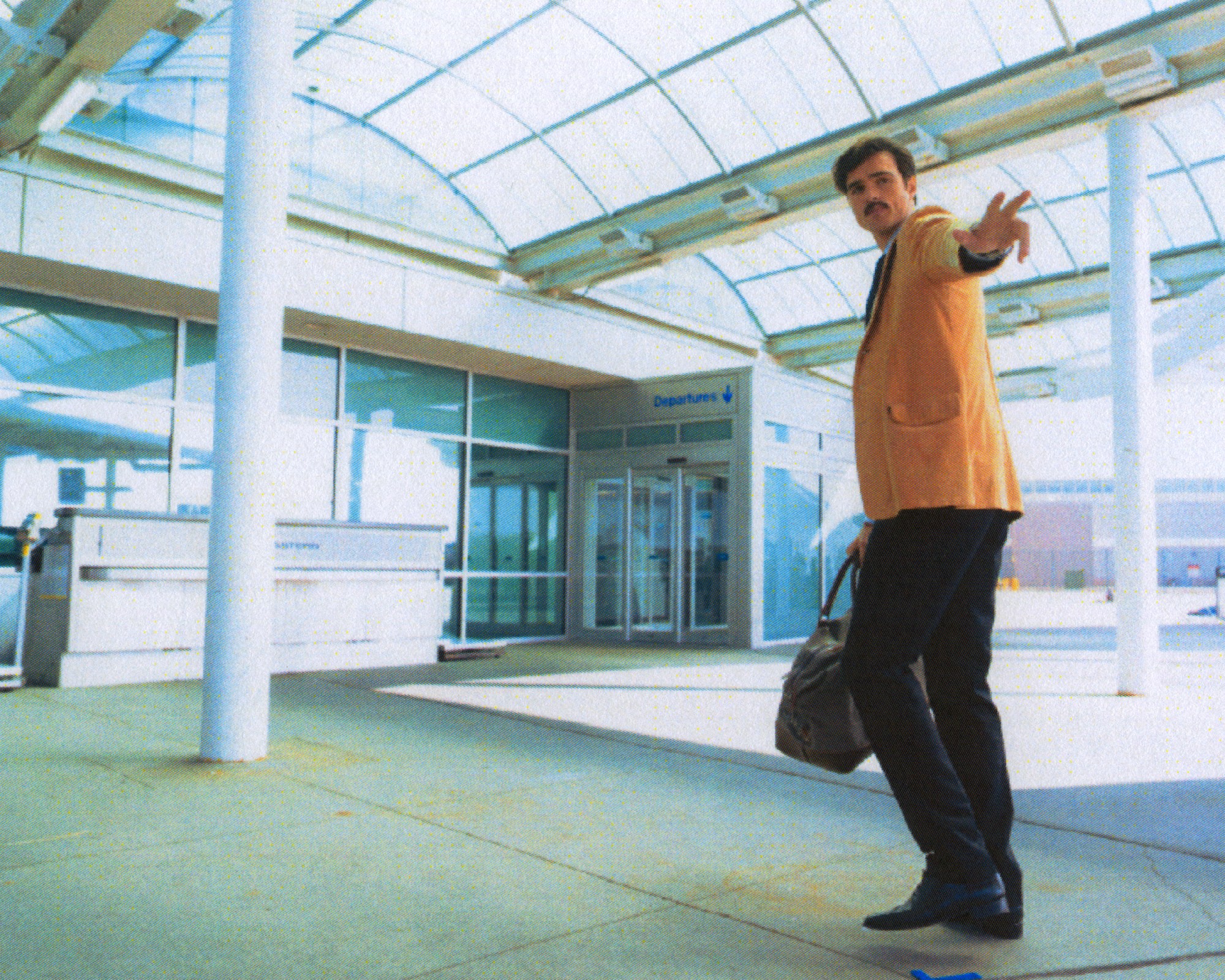

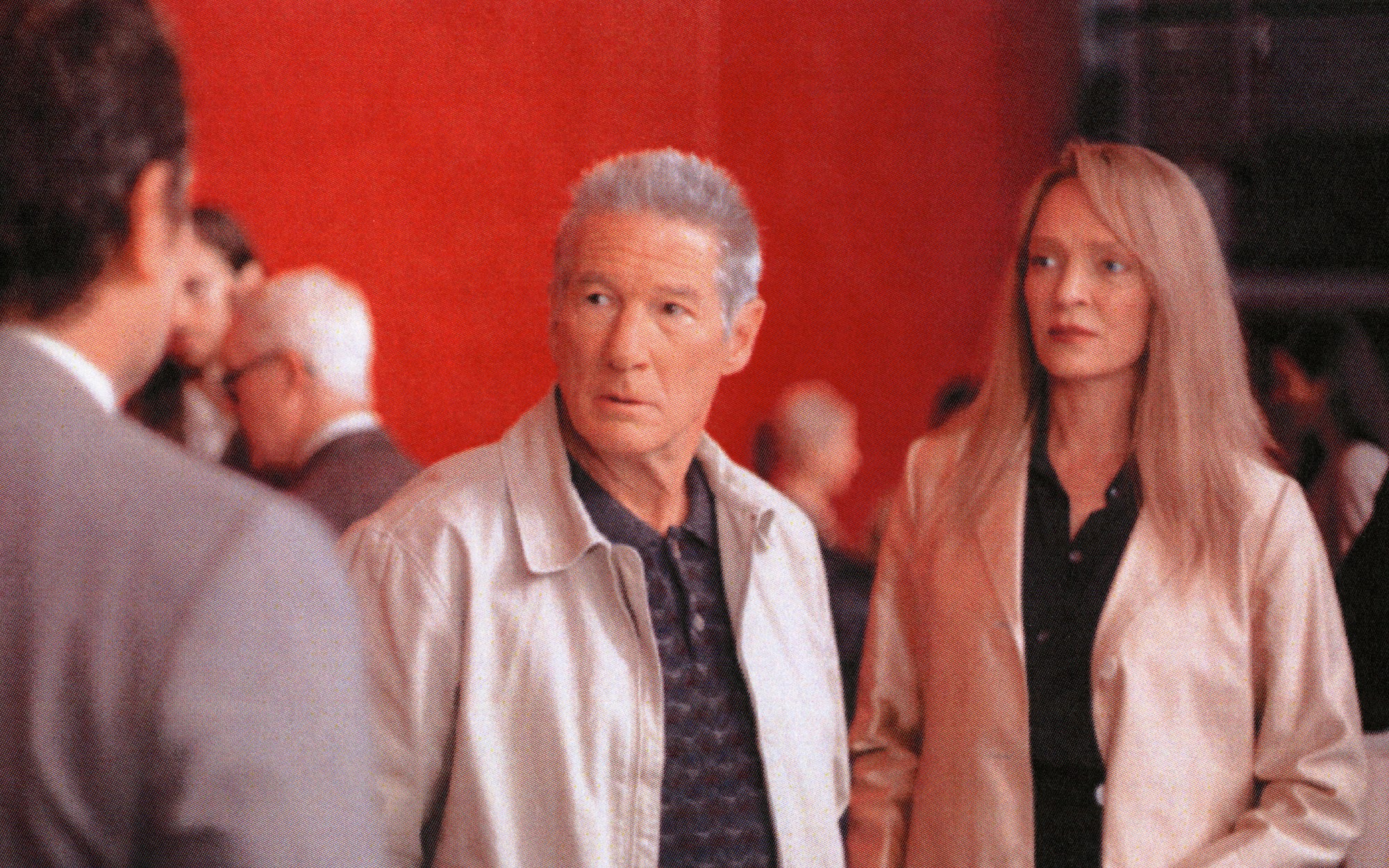

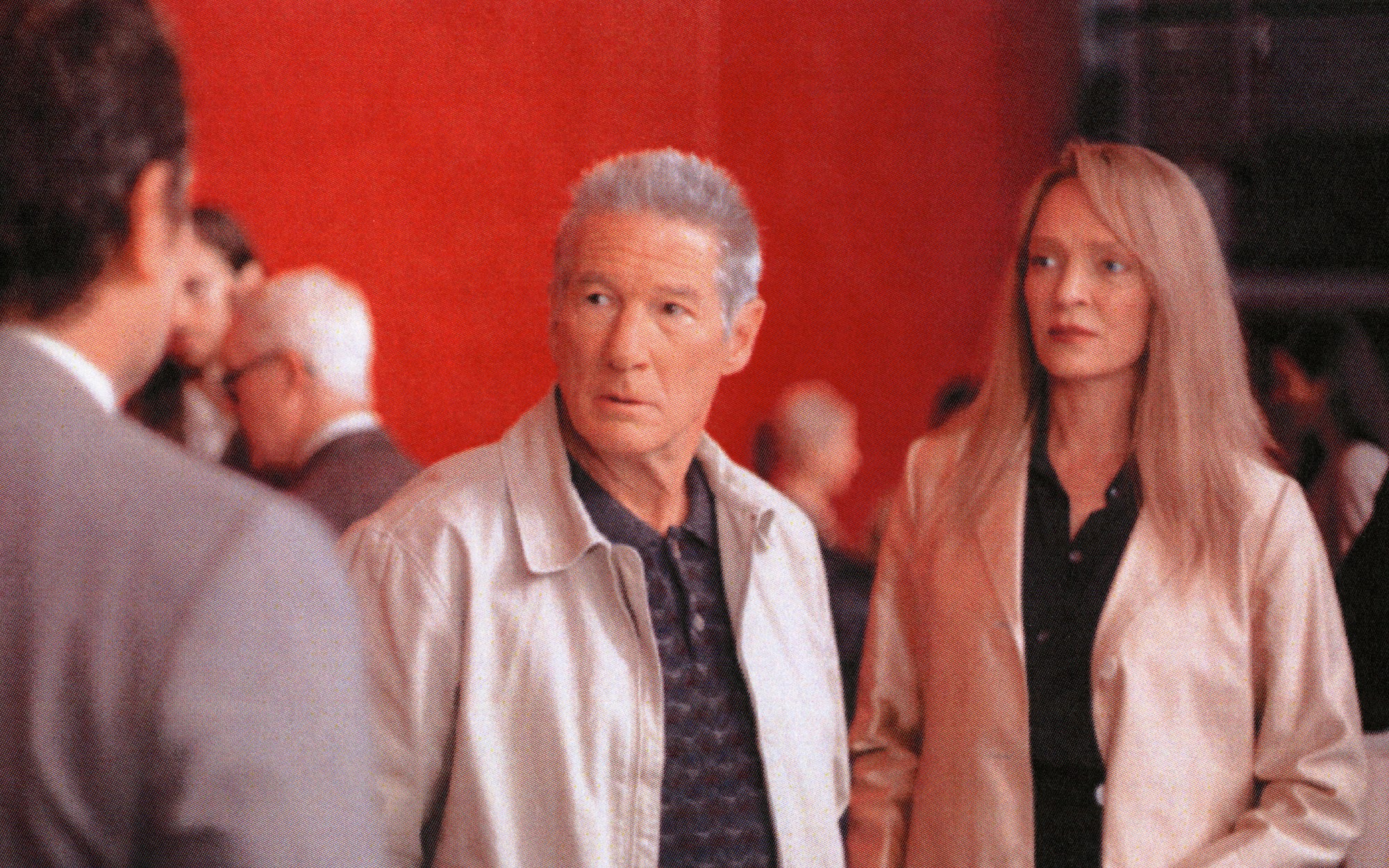

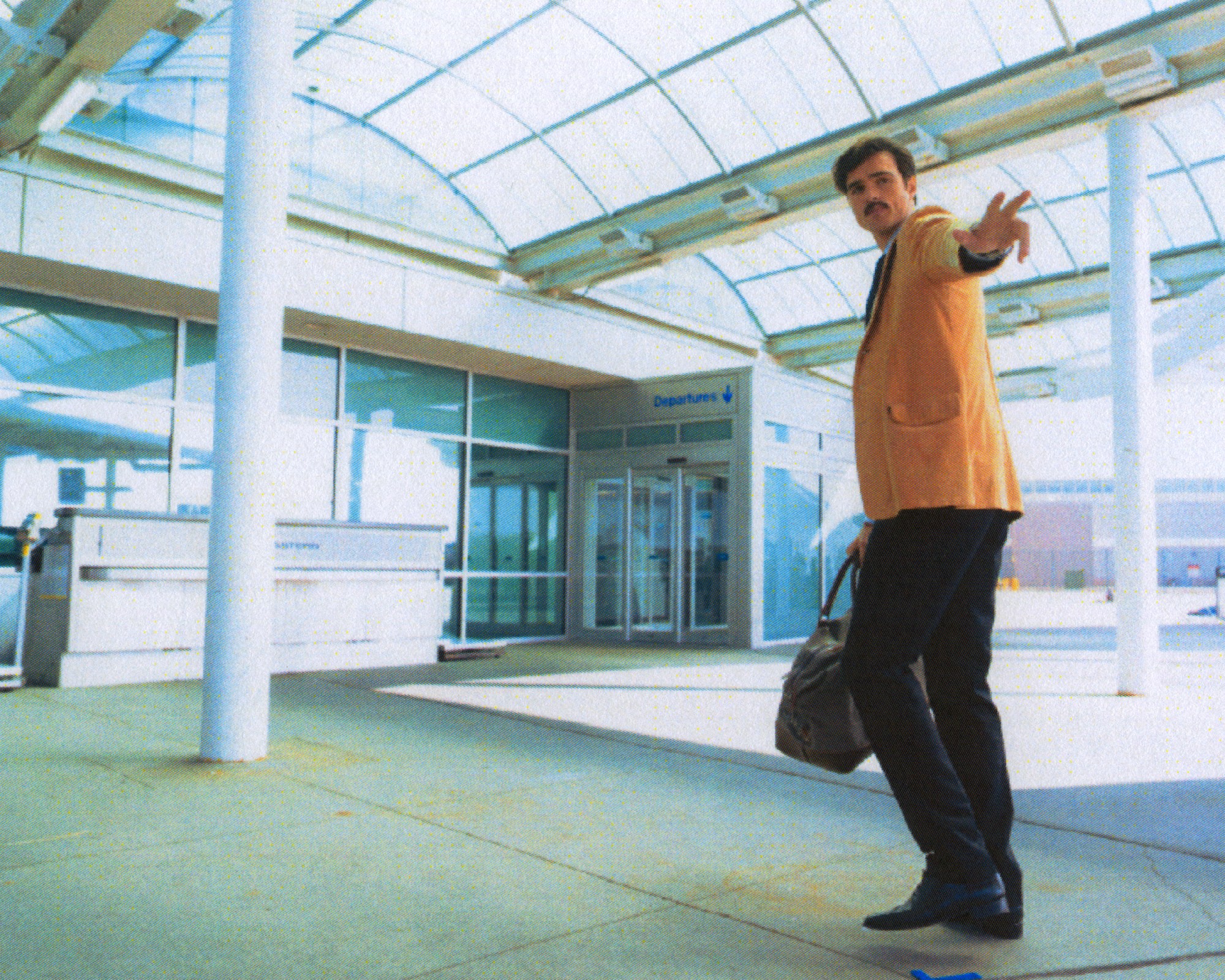

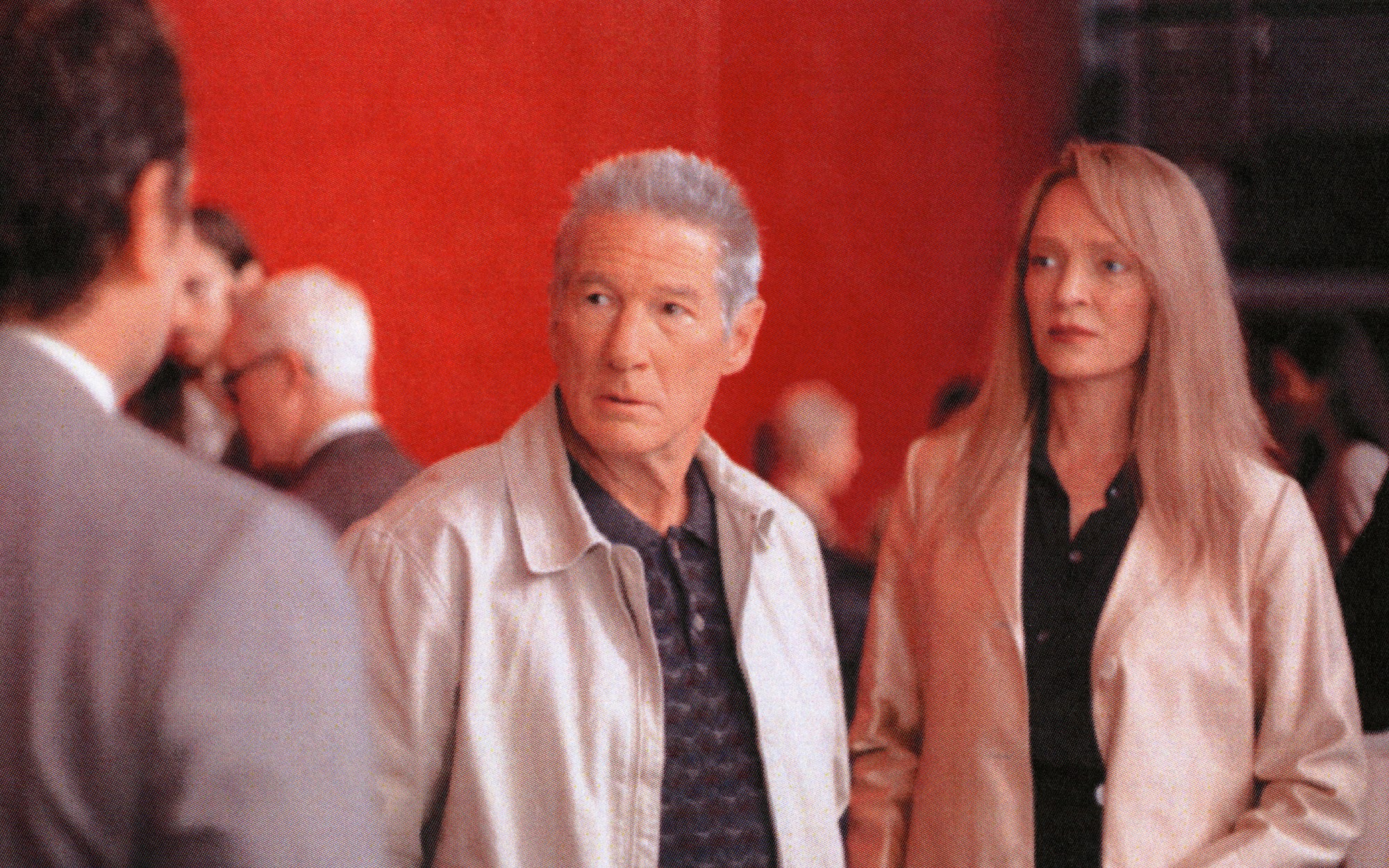

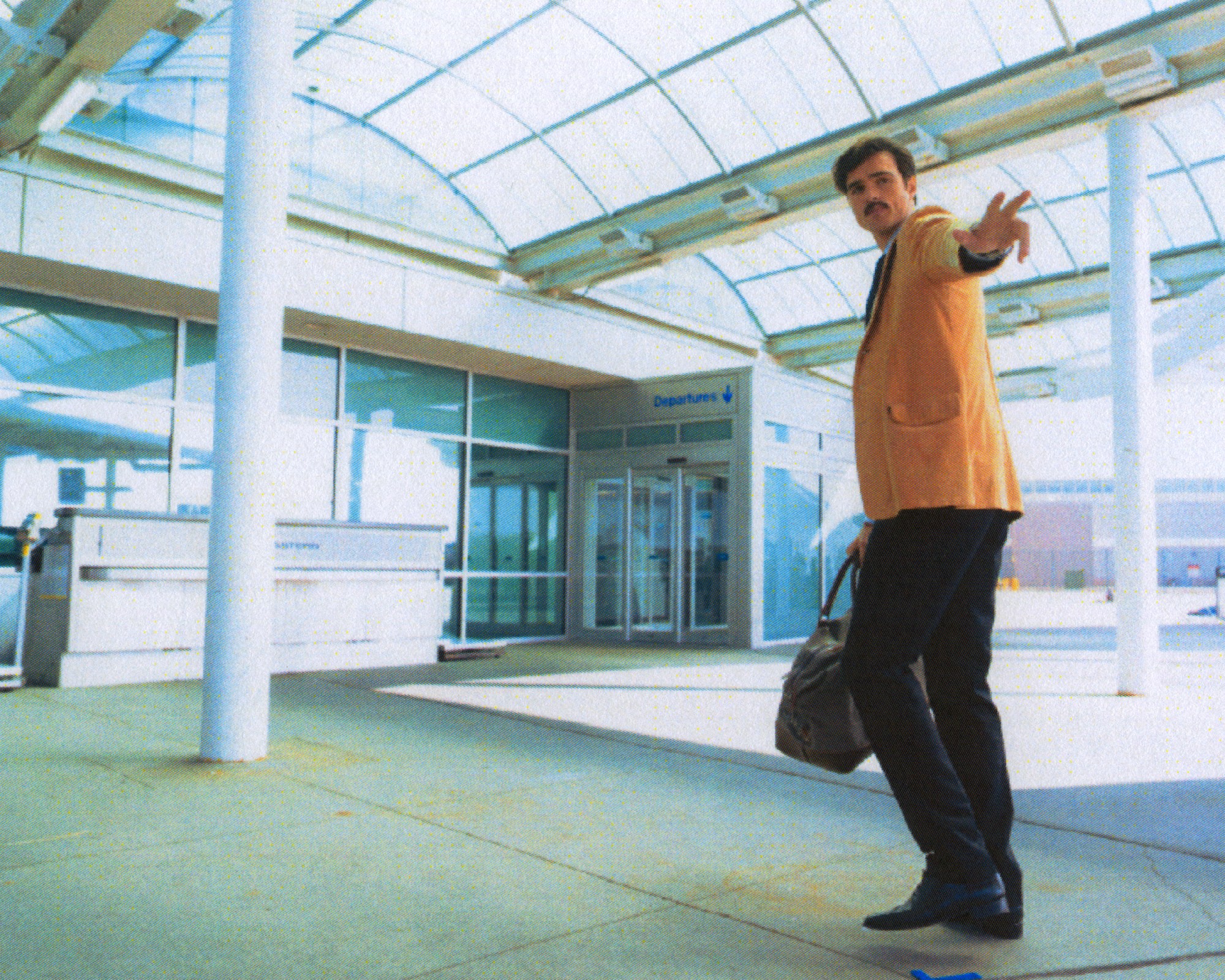

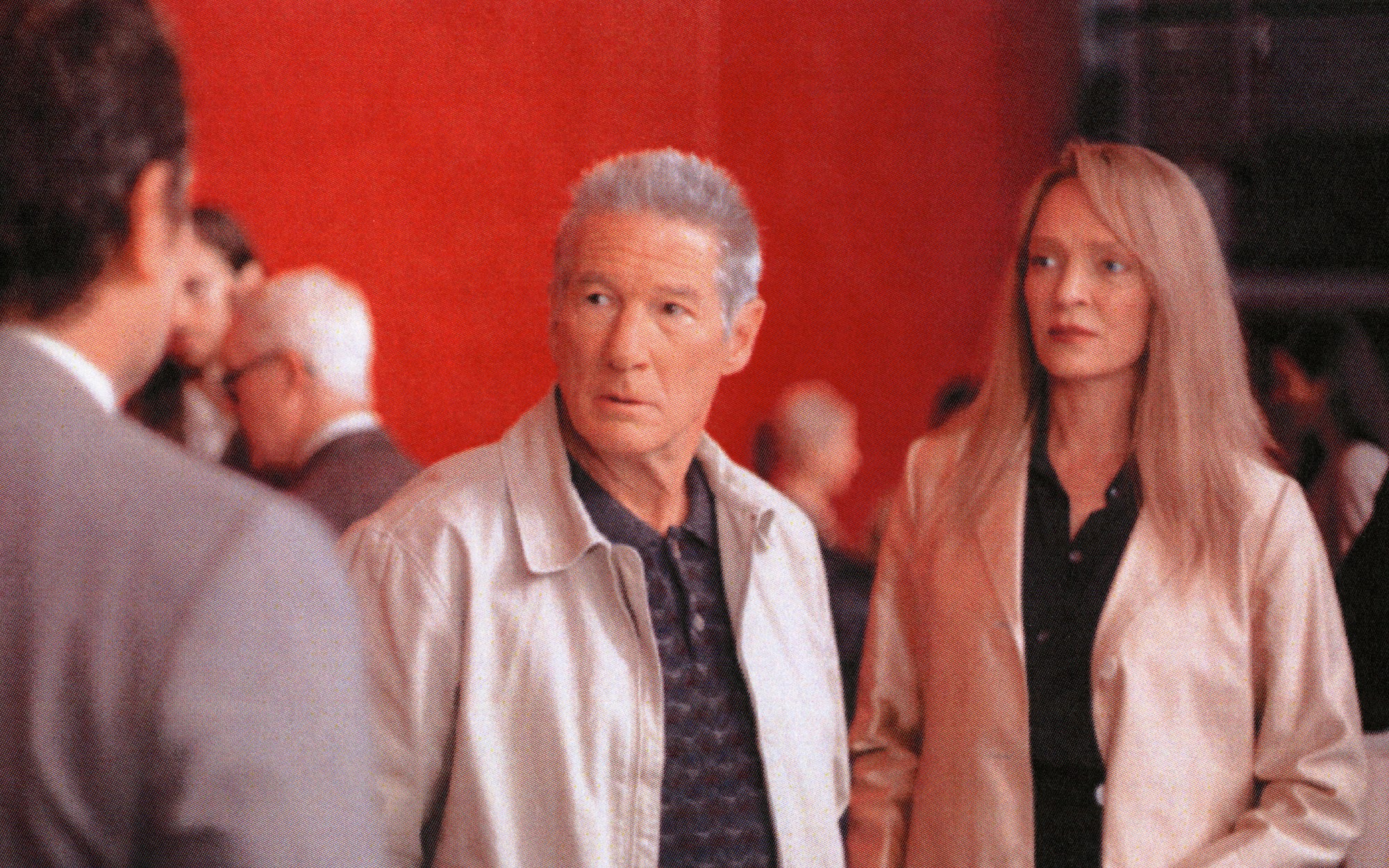

Oh, Canada, based on the novel Foregone by Schrader’s previous collaborator and late personal friend Russell Banks, is a prismatic tour through the tortured memory of an ailing Vietnam War draft-dodger. Schrader’s one-time American Gigolo star Richard Gere portrays the protagonist, Leonard Fife, in old age; a moustachioed, occasionally jock-strapped Jacob Elordi assumes the role in flashbacks. As Leonard commandeers a former student’s tribute video for his final confession, his personage unravels in a stream of guilty consciousness, the purging of a soul weighted with a lifetime of infidelity, cowardice and sin.

The details of Schrader’s biography are often recited for how cleanly they map onto his creative sensibility: out of a strictly ascetic Calvinist upbringing, he heeded the call from the great Pauline Kael to become a film critic, later authoring the essential film-theory tome Transcendental Style in Film in part as a statement of artistic purpose. He went on to write the script for Taxi Driver that won Martin Scorsese the Palme d’Or, soon afterward taking the director’s chair himself, launching a half-century career consistent in its uncompromising view of human imperfection. Schrader spent years alternately struggling and thriving under addiction, and while his work ethic hasn’t slowed a bit, he’s eased into an elder-statesman role in which he issues his proclamations in the form of rough-edged Facebook posts giving studio PR reps regular conniptions. (From March of this year: “Will Dune 3 be made by AI? And, if it is, how will we know?”)

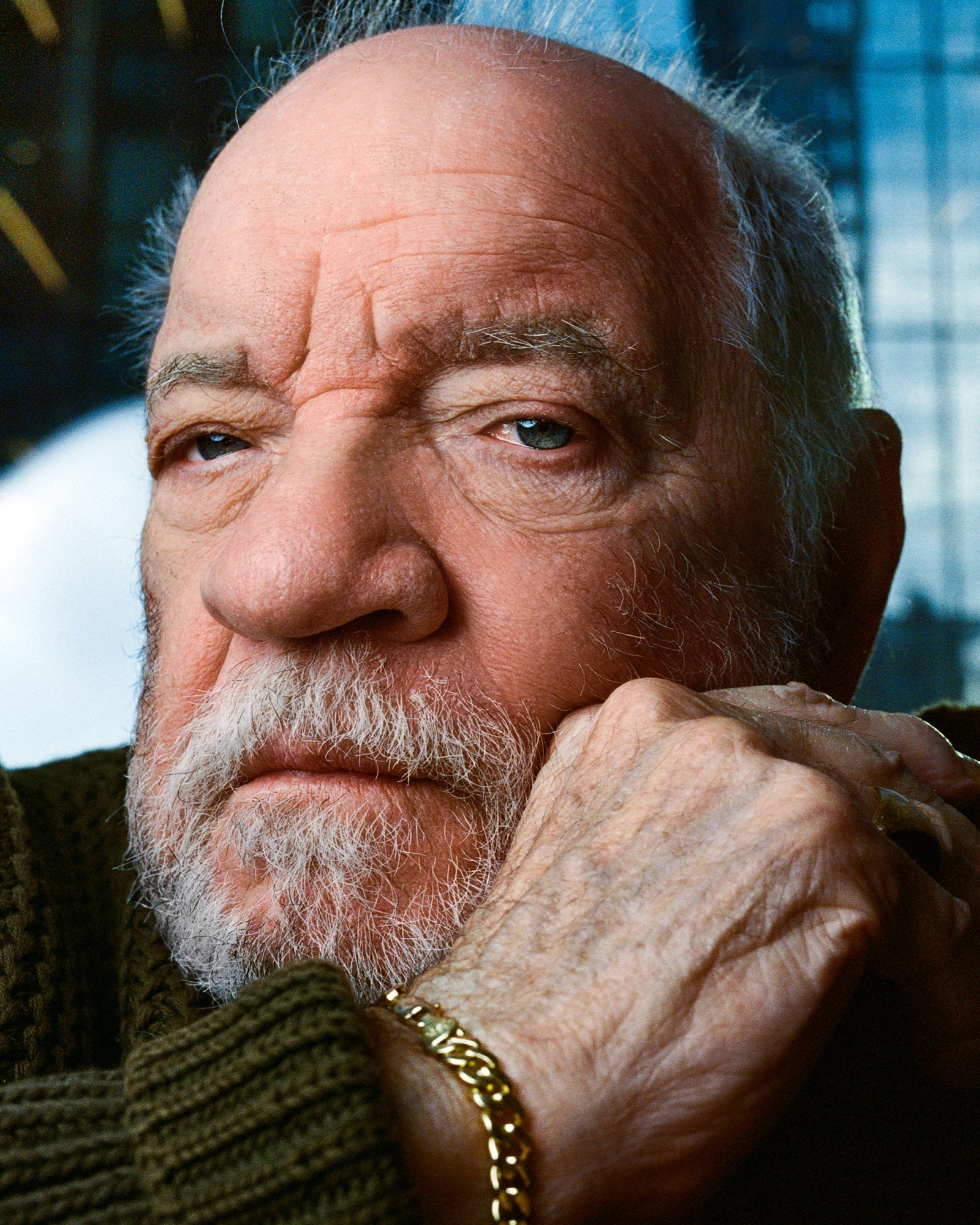

In light of Schrader’s many ups and downs, the personal significance in the story of an aged man looking back to catalogue his transgressions may seem clear-cut. But even though he lives in one of New York’s toniest retirement communities, his wife Mary Beth receiving Alzheimer’s care just downstairs from his apartment, he cultivates a complex relationship to his own mortality neither blithe nor fearful. As he holds court from his usual table at the Coterie Hudson Yards’ penthouse restaurant, his skin a little more weathered compared to when I saw him last, Schrader remains inquisitive, stubborn, irreverent and utterly unconcerned with what anyone else might think of him.

While sharing his thoughts on a Hollywood in shambles, Elordi’s movie star potential, the good ol’ days of porno cinemas, and death in all its forms, Schrader displays a bleak yet undespairing sureness of dark days to come – together with the equal, unbothered certainty that there’s nothing for us to do but get back out there and continue the work.

Discussing Oh, Canada, you’ve mentioned the summers you spent visiting writer Russell Banks upstate at his home in Keene Valley. What were those times like?

Russell had a home up there, about halfway between Lake Placid and the Hudson River, really beautiful. He was a great guy, a great raconteur, which meant he had great friends. He had a compound with a house, an office, and a guest house that took the pressure off of hosting. During the summers, he’d make his home available to whoever wanted to come up: Paul Theroux, William Kennedy, Joyce Carol Oates, interesting people. About a year and a half ago, maybe more, I called to ask when would be a good week for another one of these visits, and he said, “Maybe not this year,” because he was in chemo. I knew he’d written a book about the death process, though I hadn’t read it. He’d sent it to me, but I hadn’t cracked it. But I knew now was the time for me to write and direct my death film, because you can’t do that on your deathbed. Maybe you can write a poem, but you can’t make a whole film while you’re dying. It’s best to do this sooner than later.

Do you feel, having completed this film, that you’ve said some things you’ve been waiting to say?

Well, you never run out of those, at least hopefully not. There are more death films to be made. The issue was that I’d tried unsuccessfully to do a dementia film, but that was taken away from me and recut, (Dying of the Light, with Nic Cage). And I noticed, in the years after, as several other dementia films came out, that they were all sort of better than mine. I realized that I hadn’t really stuck the subject matter, and that was one of the problems I had with the cut of the film: I didn’t think I’d gone far enough. I went back to the producers on Dying of the Light, asked for reshoots. That’s when they told me – and at this point, I’m dealing with hedge fund investors instead of studio guys – that I had already shot this action film with Nic Cage, I’d come in on budget, shot five good action scenes, so they said they expected a 17% return.

The math is that precise?

Theirs is. “Why would we pay to reshoot? We’ll get even less than 17%!” That was when I saw that the old unstated contract between artists and studios had fractured. When I began, you didn’t really have to fight for final cut, because you were working with people who understood movies and liked movies and wanted to make the kind of movies they liked. The movie gets made, you have a difference of opinion, you work it out. Sometimes this makes the film better, sometimes worse, but that’s the process. Then there was a change, the collapse of the studio system and equity money rushing in. These people don’t particularly like movies, but more than that, they don’t really see them. That’s when I understood that I had to keep final cut, that the day had come. Then I used Nic to get it on the next film, Dog Eat Dog. “Tell them you can’t work with Paul Schrader again unless he gets final cut.”

And that worked. Once we’d shot, they wanted me to change the ending, because they didn’t like Nic kind of doing Humphrey Bogart. They asked if I’d recorded another option for the ending, and I told them I hadn’t, and they told me that was unacceptable, and I told them, “But you forget! You have final consultation. The cut is mine.”

“I think my death will have as much meaning as my dog’s”

To whatever extent a person might be pessimistic about the state of filmmaking, the outlook must be even more dismal on criticism.

Cineaste is still around, they’re good. There are still publications out there, it’s just that— [A small man approaches the table and tells Schrader, “Nice to see you again! Thank you for what you did!”] Yes, yes, thank you. The publications are out there in a social media sphere. In the heyday of good criticism, there were maybe a hundred good critics, and ten important ones. The number of good critics has risen, but the number of important critics is, I don’t know, maybe two or three.

Is it ever unsettling how prescient the doomsaying of First Reformed turned out to be? You’ve got a guy talking about “opportunistic diseases” we will live to see in our lifetime, and that wasn’t even three years out from COVID.

That wasn’t very prophetic. It’s just common knowledge. How old are you?

31.

So you’re starting to get this. I’ve got two children around your age. I grew up believing in the future, as did my father; my children have no belief in the future. That’s a seismic change. This idea that if you work hard, America will provide you and your children with a good life, things will improve — that’s gone.

I have no reason to believe the rest of my life will be as prosperous as my parents’, yeah.

Right. So, neither of my children have chosen to bring new life into this world, though I wonder how I’d like being a grandparent. Still, I understand the choice, and that’s the precipitating question of First Reformed. Do I send a child into this world, knowing what’s waiting for them? I was interested in that reluctance. The current Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are climate change, global viruses, nuclear holocaust, and now the newest one, A.I. They’re all in the backstretch, and it feels like humanity’s coming along the final turn.

Oh, Canada tightens its aperture to one man on that final turn. What do you think happens after we die?

Even though I was raised to believe otherwise, I now think my death will have about as much meaning as my dog’s. And I like my dog! I miss my dog, and I’ll miss the current one when she dies, but I don’t think my death will have any more meaning than theirs.

Working with Jacob Elordi may bring this project to the attention of people who aren’t familiar with your films.

Because of Euphoria, yeah.

Have you checked it out since the shoot?

I watched a few episodes, yeah. I liked it! It’s not a regular experience for me, but I enjoyed them. There was one day on set when a group of admirers had gathered nearby, and Richard walked out to say hello to them, assuming they were for him, only to find out they were all here to see Jake. He’s going to do well. Doing this was a good move for him, but now he’s got one big test left as a movie star, and that’s Heathcliff. If he can play Heathcliff in this new Wuthering Heights, he can do it all.

Seeing photos of you from over the years, you’ve always been a fashion-conscious sort of person. How would you describe your personal sartorial sensibility?

Well, I’ve had to tone it down. I’m going to a dinner party tonight, so I’m putting on the navy suit. I remember saying to Richard [Gere] on American Gigolo, “I think American men are getting sick of looking like bums. Brando, Saturday Night Fever, I think we’re gonna see people looking a little better. We’re on the cusp of a neo-Edwardianism.” Richard did not agree with me at the time, but once the film was over, he came around. And now that everyone has a camera and tape recorder that they can activate in seconds, I can take a picture of you and you can’t stop me. So people dress for that.

Your work always addresses the moment; has the re-election of Trump changed what you want to say with the next four years of your career?

Today is Monday? That means I’m on day seventeen of sobriety. The Trump thing and a few other things combined, and I’d started self-medicating too heavily. I’ve done it in the past, so I recognised my routine. So I went back to the rooms – that’s AA slang for going to meetings – and I’ve been going for the past few weeks. I’d become a daytime drunk, but it turned out I couldn’t drink him away, so I thought I should make a change.

I don’t think he was elected by mistake. I think he was elected by choice. But what does this mean? Democracy is the only form of government that can vote itself out of existence. When you vote for a strongman, your assumption is that he’ll ‘take care’ of those other people, and that his strength will benefit you in some way. But you’re just gonna end up on a list. Everyone does.

Do young people give you any hope for the future? I know you’re working with your former assistant on her first film right now.

My former assistant, yes. And I’m meeting with my new assistant later today to work on a new script. I’ll finish the one I’m working on now – I interrupted my writing to come here – so yeah, I’ll probably finish that one tomorrow. And then the next film, Non Compos Mentis, which was going to start pre-production in December, has been pushed back a couple months. We’re looking at an April shoot now. Because of that delay, in between writing Non Compos Mentis, I’ve been able to start on this new script. I’ll give you the title, and that’s all: My Betrayal. Leaves the question of whether you’re betraying or being betrayed. By the time spring rolls around, I might even be in a place where I’d rather do one of the new ones and sell off Non Compos Mentis. I wrote it for me to direct, but it’s a genre piece. It’s noir. First one I’ve done in quite a while where I was able to raise financing without cast; that means you’ve got a good strong story. Maybe I’ll leave that for someone else to direct, and pursue one of my other ideas. At a certain point, you gotta start thinking about how many bullets are left in the gun.

I used to have a big poster of Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle with guns blazing in my bedroom. I felt some connection to him, though a 13-year-old in the suburbs really has nothing in common with him. What is it about Travis that young men are drawn to?

Well, anger, amorphous anger looking for a home. It can be your parents, but sometimes that’s tough, because some people have good parents. Some people put it on people of colour, that’s a convenient way to unload that anger. Young men feel this – I’ve felt it – and the reason I wrote that script was because I could feel that hostility in me. I owned a gun, and I realised I was in danger of becoming someone like Travis. Fortunately, for me, I was functional at the time. By creating metaphors, one could sidestep this inevitability of fate, if only for a moment.

The last time I interviewed Abel Ferrara, upon learning I live in New York, he told me I better buy a gun.

What are you going to do with a gun? If death is the goal, there are easier and more convenient ways to do it.

You know, when he told me to get a gun, I assumed he meant for protection.

I don’t know how a gun’s supposed to protect you from jack shit. A gun only protects you from someone who doesn’t have a gun.

Are you aware that you live next to the suicide capital of Manhattan?

The Vessel, yeah. They just reopened it after shutting it down for about two years.

With brand-new safety netting. What is it about the place that makes people want to fling themselves off of it?

I think that’s common to anybody who stands on something tall. You just feel an urge, a weird thing when you get close to the edge. When I’m in a high space, I try not to go too close to the ledge.

Do you have any fond memories from the heyday of Times Square’s porno cinemas?

More the L.A. ones, because that’s where I was living. I’d go to the Pussycat a lot, because at that time, they were open 24 hours a day. Transients would go in there to sleep, right up on the balcony. Warm, dry place to spend the night. You fall asleep, and the images blur in front of you in this pleasing way. That period before Taxi Driver was marked by restlessness and rootlessness, and a lot of my nights went that way, sleeping at the Pussycat. Not for the arousal, but for the cushy seats and the privacy. In the dark, no one could see you, and you’d just conk out.

There was something cool about that, and there was also something cool about the surreptitiousness. When you actually had to go to a store to buy a pornography magazine, people could see you do that. There was a place in Santa Monica that was a regular bookshop, and then in the back, they had pornos. So you’d make a show of perusing the regular bookshop, and make your way over to the other section. There was always an illicit thrill, going down the sidewalk afterward. That era of the porn stash, the hidden stash and forbidden bookshops and secret peep shows, it had a charm that’s lost when everything is four keystrokes away. Hardcore was about the end of this era.

I’ve been reminded of Hardcore as OnlyFans has gotten more popular. Are you familiar?

And there are many different OnlyFans type web sites. The idea that someone, probably a female person, can monetise their sexuality without a pimp, from their home, and collect money from it – I can’t see that as healthy for any young person, to be that close to monetising sexuality.

I worry more about customers than performers. Watching a porno, you’re here and the performers are there, in the screen. But cultivating a virtual relationship, that can start to blur things.

I recently went to Horizon of Khufu, day before yesterday. It’s on 57th street, it’s a VR interactive experience, and you’re on the pyramid in Egypt. It’s photoreal, so you’re right there. And you’ve got this guide, who occasionally gets a little handsy.

The mind swims with pornographic applications.

And horrors. You’re standing there on the top of the pyramid, looking out over this great plateau, and you really feel like you could jump off. Even though you know that if you did, you’d just hit the next piece of ground. There is no fall. And I realized while I was there, that we can finally give someone a heart attack with a movie. You just put them in an environment where they are so frightened, more than a two-dimensional movie, and they’ll actually feel they’re falling, or getting stabbed, or having a seizure.

This worries me. We’re getting reckless with some of these advances.

Yes, but that’s your problem and not mine.

‘Oh, Canada’ opens in US cinemas on 6 December

Credits

Writer: Charles Bramesco

Photography: Bobby Doherty