I will never forget the first time I saw someone with vitiligo. Because it is a moment I am deeply ashamed of. It was the first day of seventh grade and our class had been given a fun, “get to know each other” game: we were to stand back to back, and then turn around and make funny faces at each other. I swooped around and saw my partner and the splotches of rosebud-pink, messy circles dotting his skin. I jumped back in fear. “Haha, I scared you,” he said with a laugh, thinking it was his silly monster face that had frightened me. I threw out a shaky chuckle, secretly wondering if I had caught whatever “rash” I mistakenly thought he had. I ran to my desk.

I told my mom about the classmate on the way to school the next day, asking what was “wrong” with him. “He was born like that,” she told me, explaining what vitiligo was. “It’s not a rash.” It was a lot for my 12-year-old brain to process and, to be honest, it was not until seeing Winnie Harlow on America’s Next Top Model that the overlooked beauty in those butterfly-esque, asymmetrical patterns dawned on me. Unfortunately, ignorance and unwarranted fear towards vitiligo runs rampant in our world. Michael Jackson, the most famous person with the skin condition in popular culture, died with most of the public still not understanding or believing he had vitiligo, and it being the chief factor behind his skin bleaching. They thought he wanted to be white.

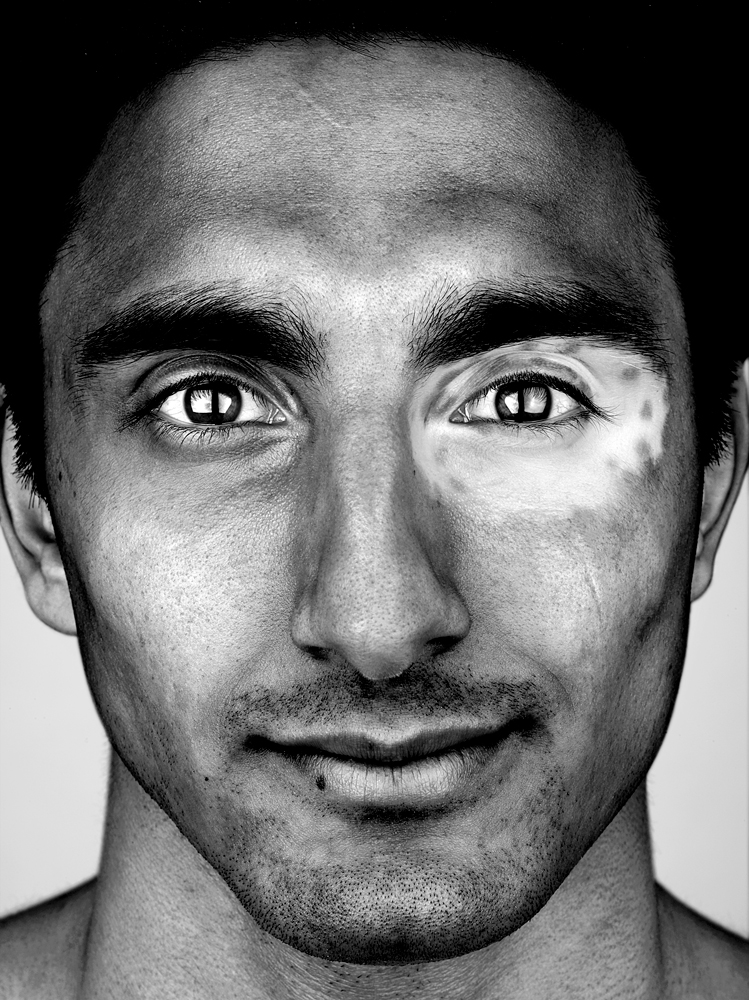

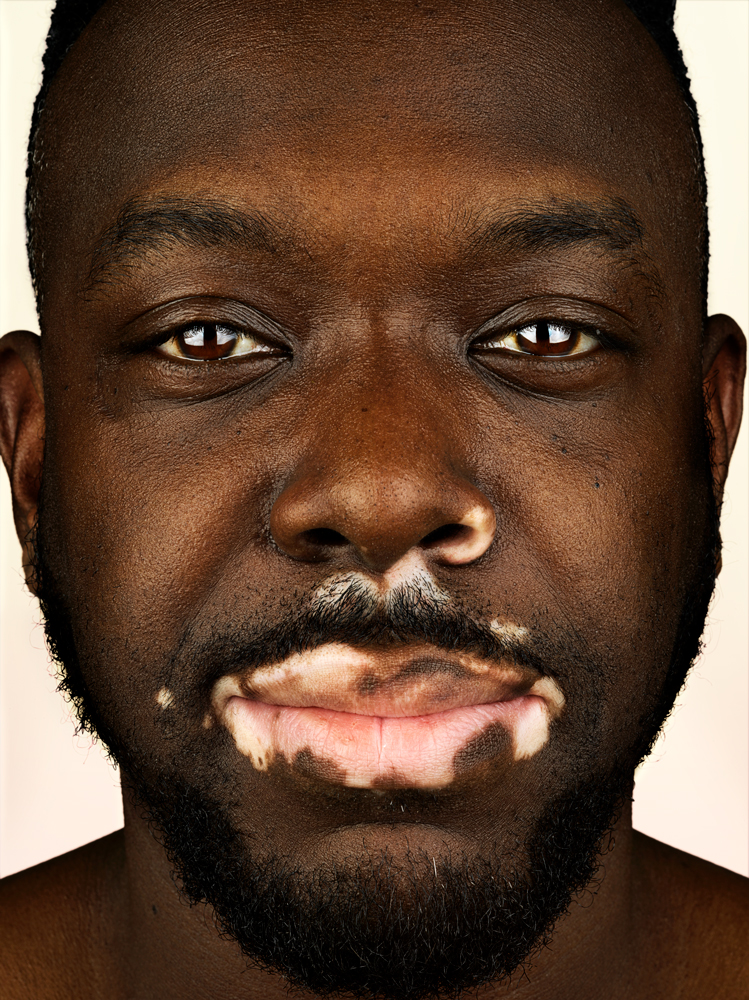

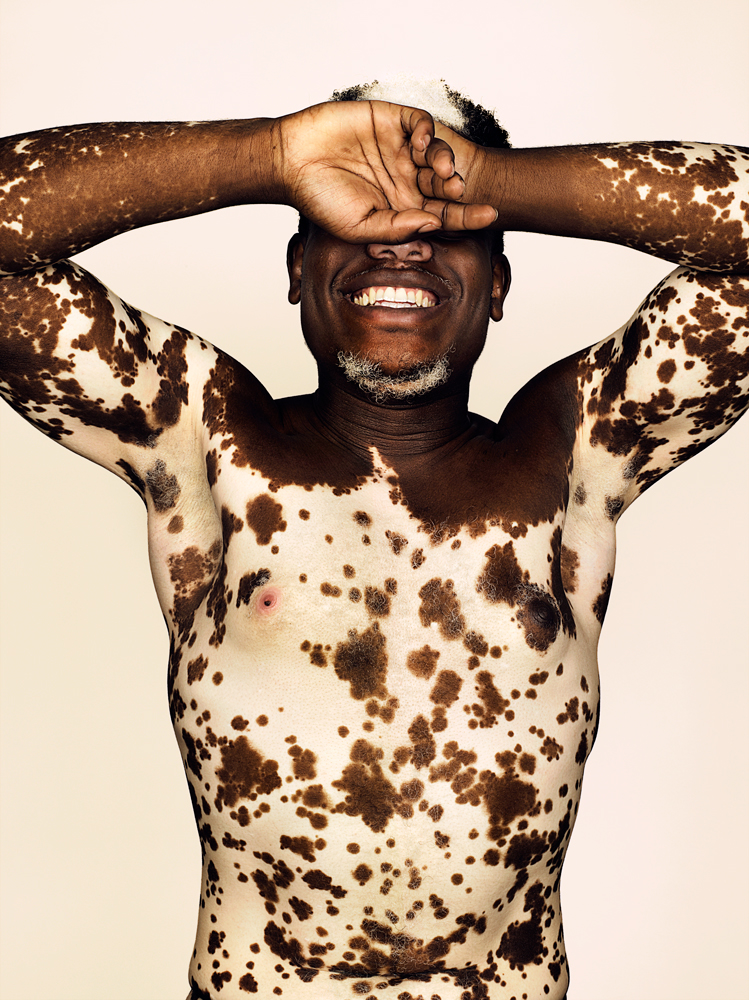

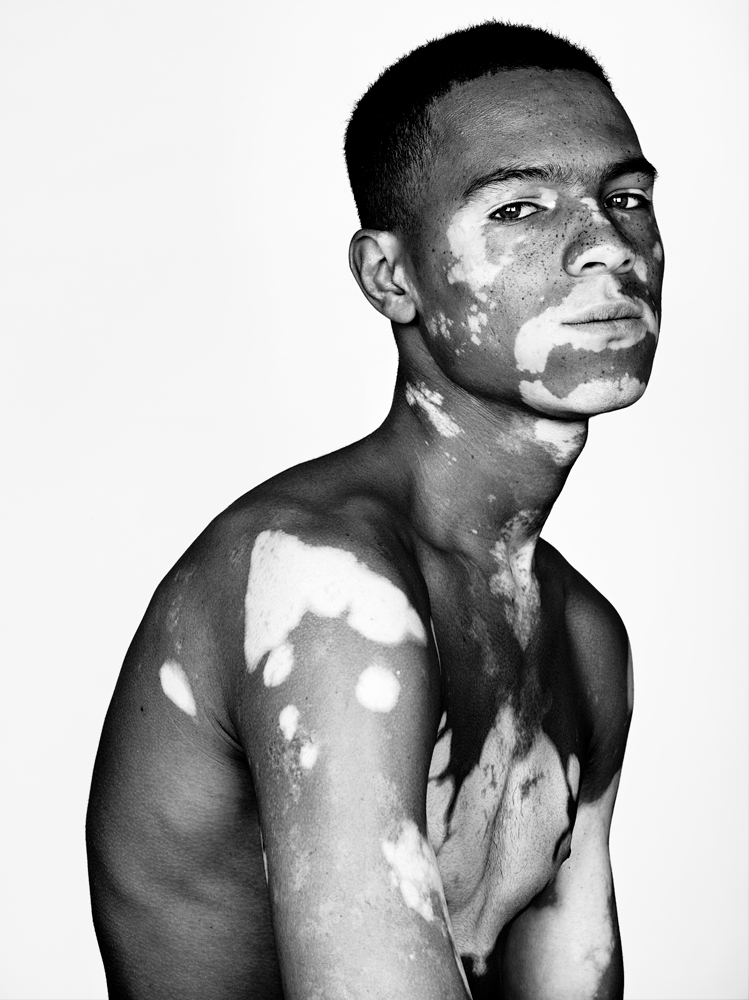

Brock Elbank is working to highlight the beauty of vitiligo with his ongoing photo series. The London-based photographer captures a mix of models and non-models with vitiligo that he finds primarily through Instagram. His brightly lit glamor shots of them strives to undo the stigma many of these subjects have encountered throughout their life, putting their identities and physical features on full display. And rightly so. They have nothing to hide.

“A lot of the times the photoshoots end up being therapy sessions,” Brock tells me over the phone. “Because we’re talking about deep stuff. I shot a girl from Trinidad and Tobago, who is black, and she lost all her pigmentation. She was whiter than I am. She said to me that it took her 15 years to get use to being her shade of white.” A lot of Brock’s subjects have taken part in the project not for vanity, but to feel part of a community. “This one guy was 50 years old and had went on vacation, got sunburned, and it triggered the vitiligo. Half of his face lost pigmentation. At 50, it was a challenging thing for him to deal with. He saw the series and thought, ‘I don’t know anyone with vitiligo and I kind of just want to do it for me and meet other people who have it.’”

Brock has shined a light on how certain physical features help us form tribes with others and shape our identities and life experiences throughout his career. Before this series, he photographed people from around the world with freckles and, before that, with beards. “I’m just always drawn to people that stand out from the crowd,” Brock tells me. “The media perceives beauty as being X, Y, Z. I find that quite dull. If you go into a model agency — don’t get me wrong these people are all incredible specimens of the human race — but they all have the six-pack, legs up to their armpits, tight bums. It gets a little beige for me.”

Finding and capturing subjects with vitiligo has been a large-scale effort for Brock, seeing as it is much rarer than beards or freckles. He finds himself most drawn to people who haven’t achieved modeling contracts or acting jobs. Because he desires to do more than simply take a beautiful photo — he wants the subjects to walk away feeling beautiful too. “I tend to find people that aren’t used to being photographed are easier to photograph,” Brock explains, preferring to forgo the industry’s standard imitable, industrial sets and shoot his subjects in his intimate home studio. “I want people to have a positive experience and be relaxed. I need to get to know that person. So I chat with them for about 60-90 minutes before shooting them.”

Brock has shot a staggering number of 35 people (and one dog) over the course of a year for this series. He is far from done, he says. “I hopefully want to do between 60 and 90, and I will probably shoot until spring next year,” he says, hoping to stage an exhibit once he’s done. If Brock has his way, that will be a lot more people in this world with more than great material for their Insta. They will have a higher-level of self confidence. “What they see as their weakness I see as their strength.”