Nothing could be more emblematic of a new era in fashion consumption than Kering’s announcement this week that Balenciaga’s growing sales are largely the result of men and millennials, two consumer groups luxury brands have traditionally struggled to crack. While other luxury brands continue to struggle to find a foothold in the men/millennial market, pushing against a congestion of streetwear brands offering the relaxed fashionability of easy-to-wear hoodies and tees, Demna Gvasalia’s era-defining aesthetic has bridged the gap in a way few storied fashion houses have managed to. According to the group’s CEO, Francois-Henri Pinault, Balenciaga has the highest growth rates in the whole of the Kering group — even more so than the jewel in its crown, Gucci. And, while the brand doesn’t publish earnings, Pinault announced the 99-year-old house is on track to reach the €1 billion revenue mark in the not too distant future.

So, what is it about Balenciaga that resonates with millennial and male consumers so much? Well, firstly men’s luxury fashion is — in general — on the rise, with retail analytics company Edited forecasting menswear to grow at a faster rate than womenswear between 2017-2020. Balenciaga’s newfound emphasis on casual-wear — long the staple of a young man’s wardrobe — has played nicely into this growing trend. A trend that extends beyond millennials, to older male consumers as well, for whom it is more socially acceptable now to dress fashionably than it was ever before.

Paradoxically, Men’s Fashion Weeks are hardly at their apex right now, with an increasing number of brands — Balenciaga included — combining collections and showing at Women’s, but Demna’s unpredictable, subversive offerings in Paris have made a huge impact over the last few seasons, and an impact that stretches beyond the cloistered world of high fashion and into the wider cultural sphere.

To uncover the success of any label, however, we shouldn’t look just to the runway for our answers. For many years now, these eye-wateringly large revenue figures of major fashion houses haven’t been driven by the ambitious, visionary designs shown at Fashion Week. For the 2015 fiscal year (when Gvasalia was installed at Balenciaga) ready-to-wear accounted for only 16 percent of the €7.9 billion Kering’s luxury division earned in revenue. A fashion show is an opportunity to present a dream, not a reality. Profit comes from the astronomical sales of accessories, fragrances, make-up, leather goods and shoes.

“While not cheap, the already-iconic silhouette of the Triple S is, in some ways, the equivalent luxury status symbol of the LV handbag, only refigured for the millennial male hypebeast.”

Research conducted by Exane BNP Paribas and the fashion consultancy VR Fashion Luxury Expertise last year claimed some brands actually lose money creating clothing collections, with the expense chalked up as are nothing more than marketing, spent in order to maintain its image. What this essentially means is that Louis Vuitton bags and Chanel No. 5 perfume are the lifeblood of the fashion industry. Hardly surprising, really. Old Parisien aristocrats picking up a few à la carte gowns every so often don’t hurt the labels with couturiers attached, but this-season’s-hottest-runway-trend at any fashion week rarely directly spikes a huge revenue growth.

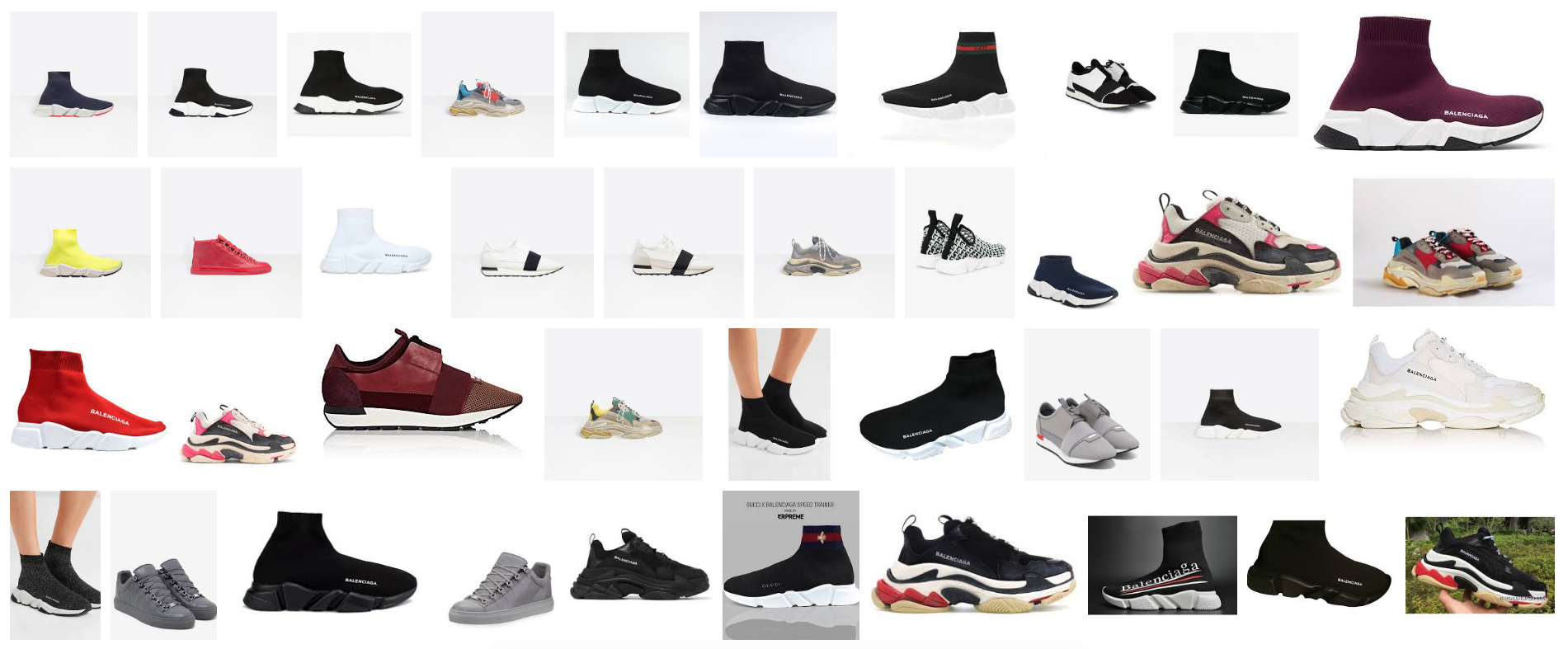

For Balenciaga, it’s not about bags or perfumes right now, it’s trainers. The Speed Sneaker and the Triple S have become two of fashion’s most instantly recognisable shoes in the past two years — the latter sparking a growing trend among big fashion houses for “ugly” styles (see: Louis Vuitton, Yeezy, Gucci). Even the infamous platformed Croc, debuted for spring/summer 18, sold out instantly. While not cheap, the already-iconic silhouette of the Triple S is, in some ways, the equivalent luxury status symbol of the LV handbag, only refigured for the millennial male hypebeast.

Search the hashtag #balenciaga on Instagram and you’ll be confronted almost exclusively with images of the trainer. Search specifically #balenciagatriples and you’ll find over 125,000 different results. Flexing on the ‘gram isn’t a comprehensive measure of a brand’s success — but it does shed light on what younger consumers are coveting most. (See: Gucci). Even Google image searching “Balenciaga” yields exclusive images of trainers. For a century-old fashion house famed for its structural couture dresses, this is quite a development.

What Demna has done here — the genesis of which he began with Vetements — is to cleverly create, season after season, a small number of singular “it” items, but for a broader audience. “It bags”, but make it unisex, or make them so over-the-top that they practically beg for incredulous column inches. Trainers have long been the meeting point for high fashion and male consumers, but few labels have created a trainer like the Triple S or Speed Sneaker that speaks as loudly as a Chanel handbag. “The rise of ‘it’ items are not limited to bags,” wrote The Fashion Law last year. “Hoodies, bomber jackets, statement jeans, and other eye-catching garments have taken center stage in street style shots.” In essence, he’s taken a tried and tested model that targets older female shoppers, and broadened it to appeal to young men as well. Combine this with the lower price-point of T-shirts, and a growing demand for luxury fashion amongst men, et voila.

“Trainers have long been the meeting point for high fashion and male consumers, but few labels have created a trainer like the Triple S or Speed Sneaker that speaks as loudly as a Chanel handbag.”

The model isn’t employed by all labels, however. The widespread ubiquity and recognition of brands like Chanel, Prada or Gucci invariably contributes to mass demand for an instantly recognisable look, logo or shape. The ultimate symbol of luxury in a mass market remains two entwined Cs, and this mass visibility paradoxically decreases its exclusivity . Balenciaga may be growing in size, but is far from reaching the dizzying heights of these fashion behemoths; there’s still something comparatively underground and subversively edgy about its luxury status. But, for independent brands like Dries Van Noten and Rick Owens, success is defined much more by the clothing.

Speaking to i-D in 2016, Rick himself spoke of his desire to push back on homogenisation of luxury fashion with a more daring collection. “I was reacting to what’s going on in fashion now: conservative and careful and commercial. The fact that I was doing things that were fragile and hard to produce and hard to ship and hard to show in a store, was an emotional reaction to the straight world we live in now.” Rick’s business is funded almost entirely by pre-collections, allowing him the freedom to exhibit whatever he wants when shows come around. “This is not a compromise. I’m not making stuff that I don’t like or that I’m ashamed of. I’m making simple things that are made the way I want them to be. The runway clothes aren’t going to be on the floor very long before the sale. So I can go bonkers. I can kind of do anything. And I should.” Conversely, it shouldn’t go unmentioned that the ugly sneaker was on Rick’s agenda long before Demna was a twinkle in Kering’s eye.

The tides are certainly changing, with Hedi Slimane soon to debut the first Céline menswear collection, and Virgil Abloh taking the helm for Louis Vuitton men’s, menswear will only grow in relevance over the coming seasons. Both designers have been at the forefront of their respective fashion revolutions in the past — Hedi pioneering the prominence of the skinny-framed man; Virgil the blurring of lines between streetwear and luxury. But it’s what they will do next that will cement them in history. If the oversized, restructured trainer fits, that is.