Sometime in the 60s, the often-misunderstood, visionary German philosopher Theodor Adorno claimed that “great artists since Baudelaire were in conspiracy with fashion,” pointing to the emergence of fashion as part of the modernist project. He wasn’t all wrong. Today, crossover collaborations between art and fashion have achieved unprecedented attention, from Louis Vuitton’s Jeff Koons-designed Monet bags to Calvin Klein’s Americana-themed flagship store by Sterling Ruby – and let’s leave aside the fashion-sponsored exhibitions or blockbuster shows à la Alexander McQueen at the Met (that’s a whole other article).

But what’s often overlooked are the efforts of artists and designers to truly examine, subvert, and disrupt the fashion industry’s politics of labour and production. This is the ambition of the exhibition Fashion Work, Fashion Workers, at CCS Bard Hessel Museum of Art, in Upstate New York. “It is the result of a prolonged period of thinking about the relationship between art and fashion,” explains curator Jeppe Ugelvig of his show, which gathers garments, archival material, and films from four radical projects spanning two decades from the mid-90s to today, including the ultimate meta-brand Bernadette Corporation, designer-turned-artist Susan Cianciolo, alternative label Bless, and post-internet sensation DIS. “What goes through all of [the projects] is an attempt to disrupt fashion,” continues the Danish-born curator and critic, who’s currently finishing his MA at CCS Bard, “while embracing fashion’s rules, they constantly try to break away from them.”

Infused with a certain postmodern irony, the cryptic, semi-anonymous NY collective Bernadette Corporation had a crack at pretty much every form of cultural production you can think of: party promoting, fashion designing, magazine editing, and filmmaking. They came together in 1994 as part the downtown party scene, when the then-23 year old Bernadette Van-Huy, a recent economics graduate, was circumstantially poached by the manager of the notorious Club USA to throw a party with her friends alongside Michael Alig and his Club Kids.

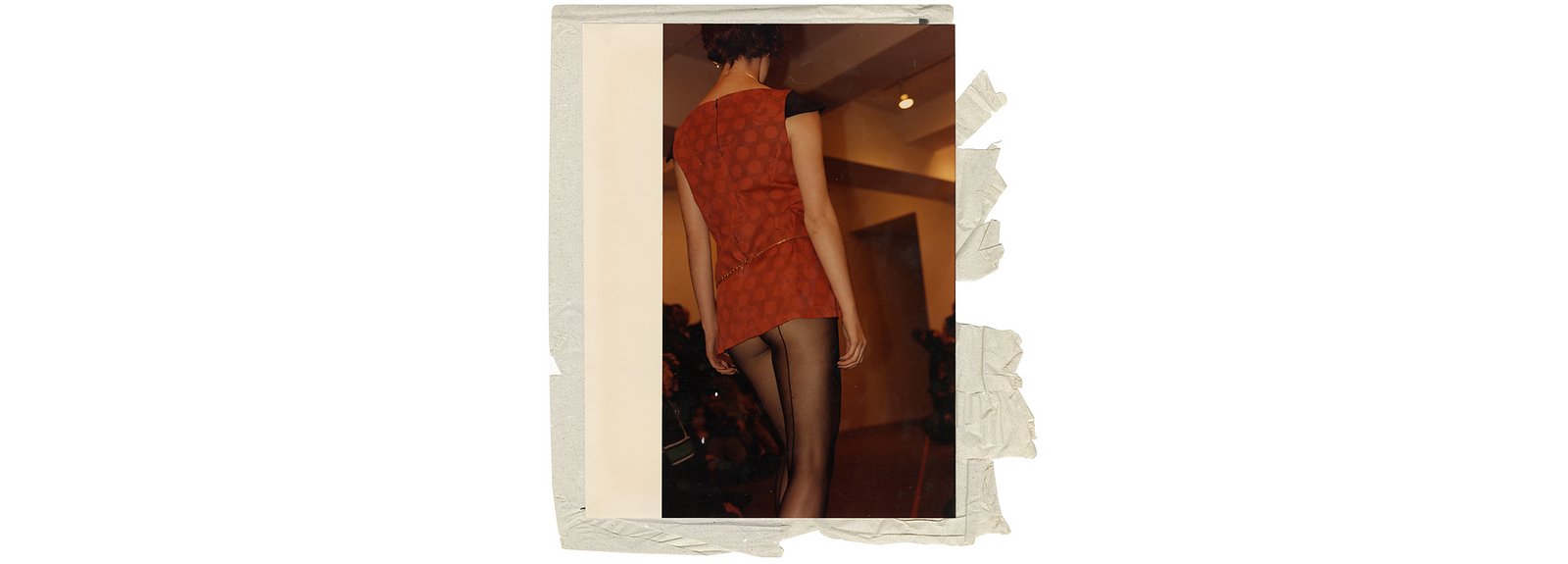

The following year, and just as circumstantially, Bernadette and her newly-formed clique of cultural rebels ventured into what became their cult fashion line. For three years only, Bernadette Corporation (who have since received retrospectives at New York’s Artists Space and London’s ICA) operated as a ready-to-wear brand, staging catwalks and releasing nonsensical, biannual collections, often complemented by thrift shop clothes with their logo stitched to them. “They broke all the rules,” comments Ugelvig, as we look at archival pictures of cozy-looking, DIY runway shows shot by Wolfgang Tillmans. “Identity was becoming something you could buy in a store, and they were interested in mining that.”

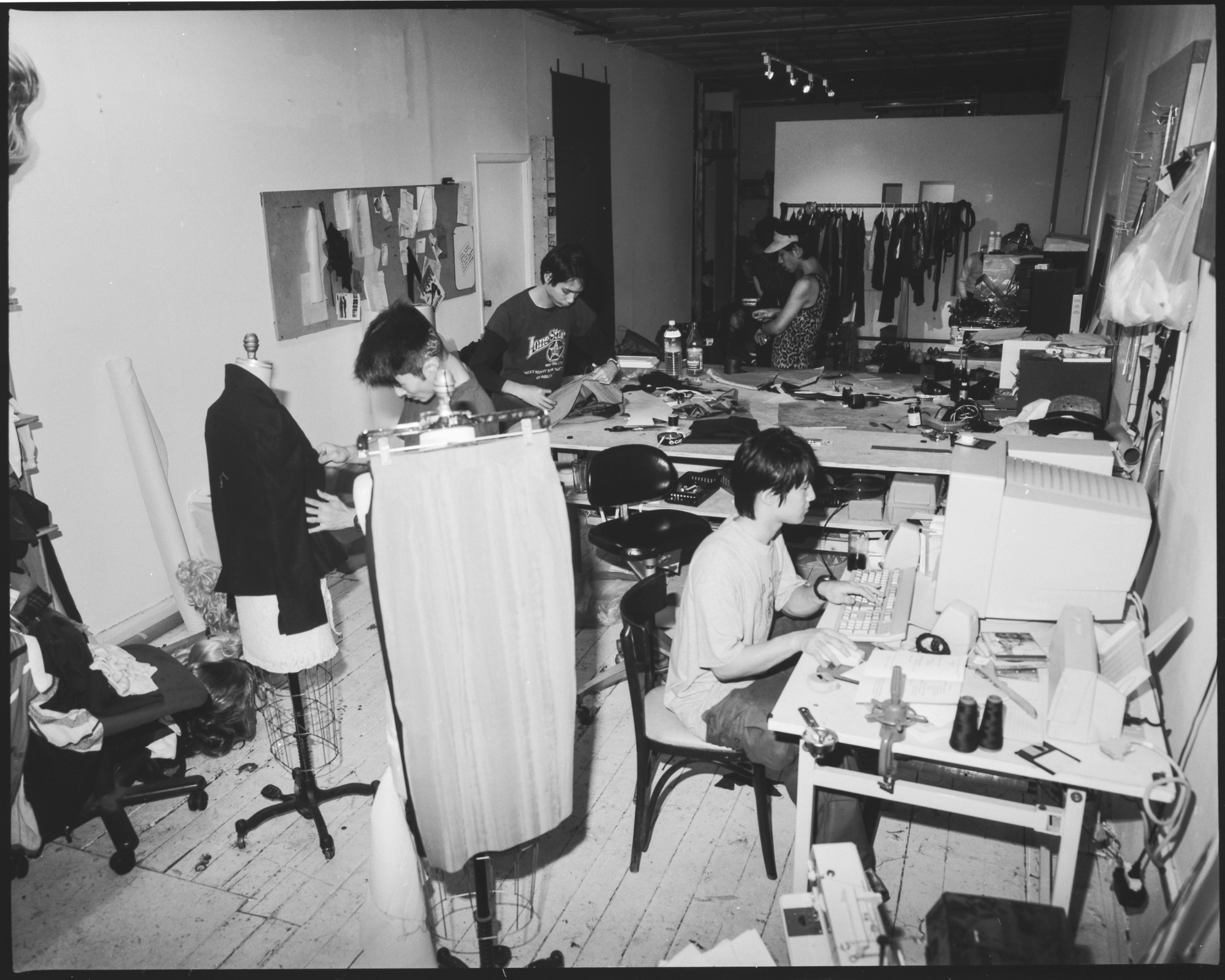

Around that time, Parsons graduate Susan Cianciolo operated at the intersection of New York’s art and fashion scenes, staging conceptually rigorous presentations with her eponymous label Run. Launched in 1995, while Cianciolo still worked part-time at Kim Gordon’s fashion brand X-Girl, Run’s first collection (simply called “Run 1”) took place at Andrea Rosen Gallery on Prince Street, and was put together with the help of artist friends Rita Ackermann and Bernadette Van-Huy (that’s right, from Bernadette Corporation). Combining elements of garment design, fine art, and performance, the label quickly gained a cult following, praised for its raw, unique designs. Until closing shop in 2001, Run engaged in original forms of production, often involving the designer’s friends and family members – partly out of financial necessity, but more importantly out of a desire to create a community around the project.

“I probably needed to end for physical and mental rest and rewiring after years of nonstop output and production,” recounts Cianciolo, who is now best-known in contemporary art circles, having participated in the Whitney Biennial last year and exhibited internationally. Yet, she explains that she finds a sense of belonging in both art and fashion, “perhaps because they seem the same to me,” she continues, “as I am making the work, it uses many mediums that have and still fit into both.”

The 90s represented a shift in the fashion industry, profoundly shaped by the neo-liberal turn. This culminated in the advent of fast fashion, expansion of luxury conglomerates, outsourcing of subcontractors to developing countries, and ultimately, the overt marketing of cultural symbols in the form of globally recognized brands (a nightmarish vision predicted as early as 1944 by Theodor Adorno under his notion of “culture industry”). In that context, Bernadette Corporation’s cultural eccentricities and Cianciolo’s lo-fi, community-driven production model appear less like a satire than a political statement.

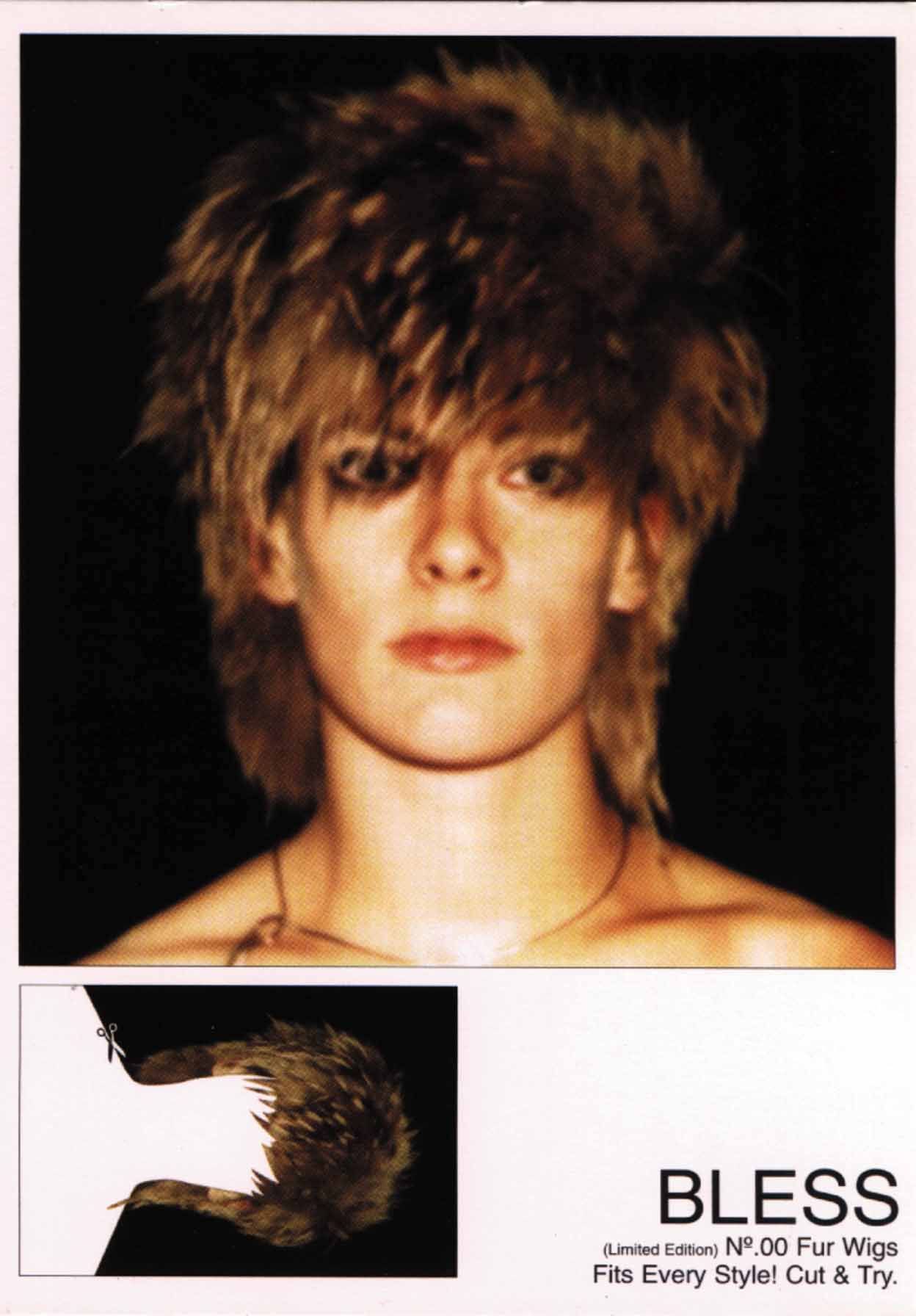

On the other side of the pond, the Paris and Berlin-based duo BLESS has spent the past two decades rethinking conventions of fashion production and presentation. Transcending the traditional categorisation of art, design, and ready-to-wear, the studio (formed by Desiree Heiss and Ines Kaag) has defined an idealist approach which, in their own words, functions as “a visionary substitute to make the near future worth living for.” They present their interdisciplinary work exclusively through “services,” which they display concurrently in museums, art biennials, and fashion stores around the world. “They’re an interesting model,” argues Ugelvig of the pair, who were discovered by Margiela circa 1996 after taking out an advert in i-D to promote their fur wigs, with money borrowed from their parents. “It’s like an open-ended process.”

But in the following decades, the advent of the digital age somewhat spoiled the party. Online shopping, algorithm marketing, and Instagram influencers are the new protagonists of an increasingly problematic industry that won’t stop mutating — faster and furiouser. Since its founding in 2010, New York-based collective DIS has examined the status and politics of the image in a post-digital consumer society, operating simultaneously (not dissimilarly to Bernadette Corporation) as an online magazine, curatorial platform, a party promoter, and art producer.

For Watermarked , a 2012 campaign commissioned by Kenzo (featured in the exhibition), DIS created a short film populated by traditionally handsome male models of different races (a nod to the legacy of Benetton’s somewhat culturally clumsy representation of racial diversity) and embellished with elevator-like music. The young men act out stock photography vignettes — shaking hands, sipping on a cup of coffee, hugging — in what appears to be a highly corporate environment, creating at once a sense of irony and discomfort. While the video was purposely licensed under a Creative Commons license, enabling its free use and circulation, it is adorned by a large corporate watermark of the Kenzo logo.

“For the brand it functions as a promotional campaign,” explains Ugelvig as we watch the video, which was recently featured at the ICA Boston’s group show, Art In The Age Of The Internet, 1989 To Today, “but for DIS this constitutes a work of art. That doubleness is very interesting,” he affirms.

A number of other artists spring to mind as relevant candidates to contribute to this discourse. Kim Gordon with her DIY label X-Girl, Canadian artist Chloe Wise and her subversive Chanel bagel bags, and Mexican artist Pia Camil with her art fairs ponchos and second-hand t-shirts installations — perhaps a less western-centric commentary on post-NAFTA, cross-border commerce. But Ugelvig insists that Fashion Work, Fashion Workers doesn’t have the ambition of a survey, at least not until it has a potential future destination.

“A lot of people, especially in the art world, are quite allergic to fashion,” jokes Ugelvig, as we discuss the everlasting, restrictive perceptions on high-brow versus low-brow culture. But with such abundance of thriving practices — old and new — constantly pushing the boundaries of what constitutes artistic and fashion work, how much of that compartmentalization still makes sense? “The fashion industry is horribly problematic,” asserts the curator, “which is why it’s urgent that the art world begins to embrace practices that would thrive much better outside of it.”

“Fashion Work, Fashion Workers” is up until May 27th at CCS Bard Hessel Museum of Art.