Domino sugar, lottery tickets, old-school paper coffee cups, and plantain chips. These items, commonly be found in your local New York City bodega, are also featured in Dominican-American artist Lucia Hierro’s current work.

Born and raised in the Inwood/Washington Heights section of New York City, Lucia’s creations mine consumer products to cultivate a conversation focused on class, race, and identity. During her first NYC solo exhibition at Elizabeth Dee Gallery in Harlem this past February, Lucia introduced viewers to Mercado, a collection of intricately constructed, larger-than-life bags filled with everyday ephemera in the form of soft-assemblage objects. Through these works she confronts cultural and economic privilege, and their relations to material objects as well as intangibles.

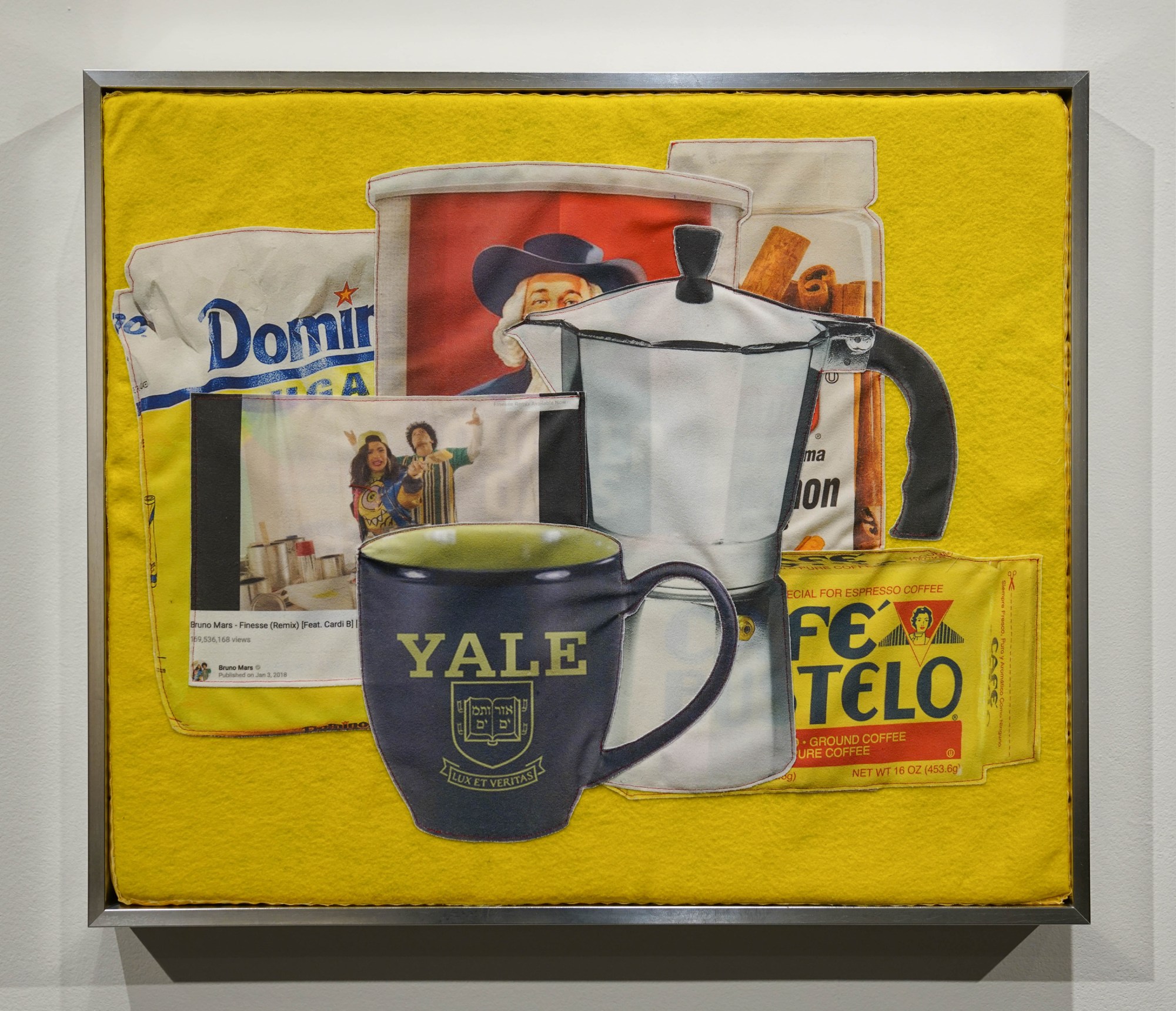

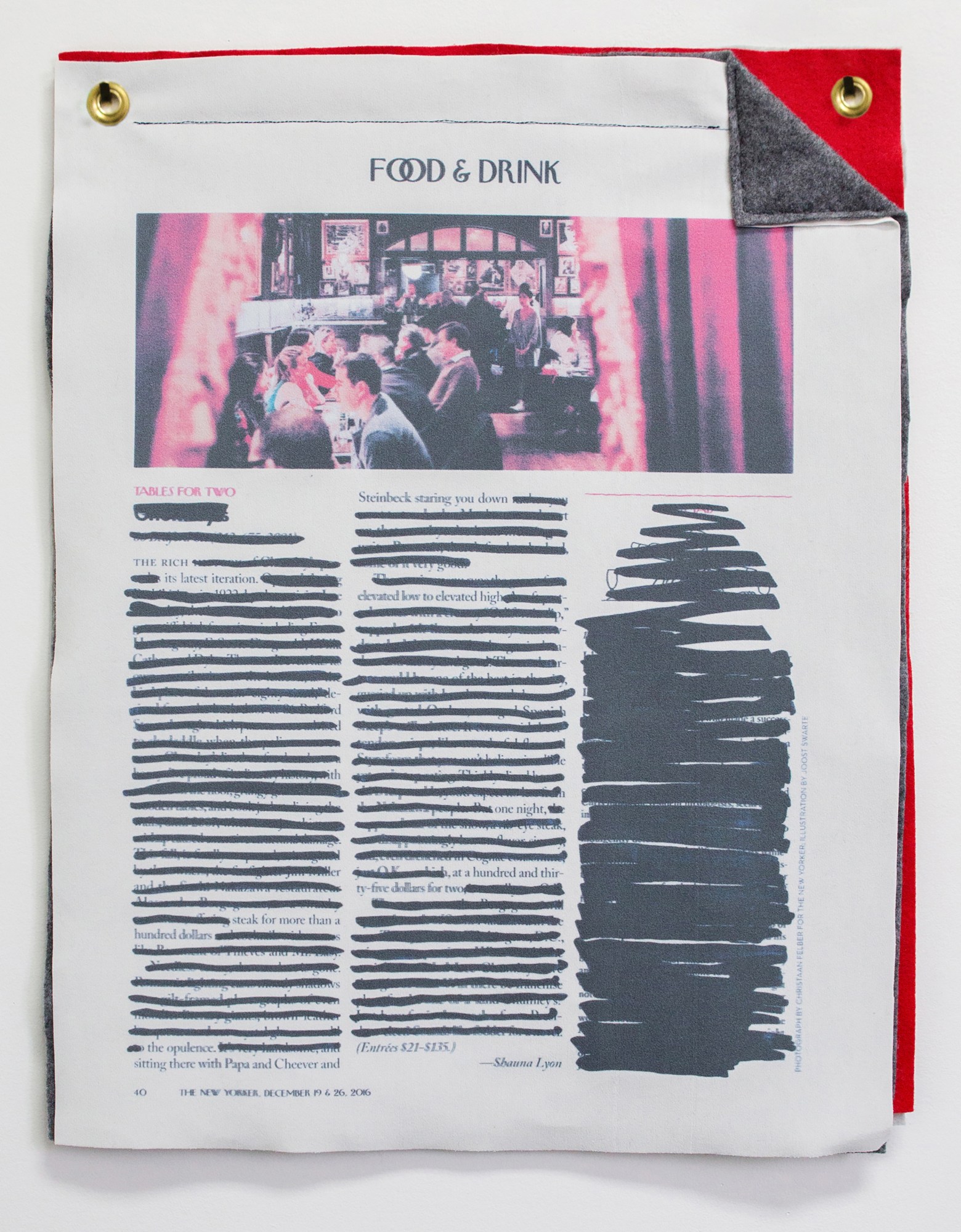

Now in residence at Red Bull House of Art in Detroit, Lucia has reimagined Mercado as a series of still-life pieces, further exploring these notions. Items such as Café Bustelo, Queso de Papa, and bodega sandwiches contrast sharply with visions of Glossier lip balm, green juice, and magazines, creating an intersection of capitalism, culture, and identity. In a time of rapid change and hyper-gentrification of cities, Lucia’s work asks us to meditate on goods and the “chicken and the egg” effect they may hold: What is our relation to that which we consume? Just how much is capitalism integrated into our identities? And, most importantly, can we hold conflicting preferences?

i-D recently spoke with the artist about growing up in a changing city, and the importance of community inclusion.

New York City, like many big cities around the world, has been changing at what seems to be a hyper-speed rate. Can you tell us a bit about how it was for you growing up there?

Growing up in New York was such a great experience, specifically the area I grew up in, Inwood/Washington Heights. My family was always at a couple block radius and walking down the street with my mom meant stopping to talk to someone at every corner. There was a real sense that we were in on something together – I understood early on that it had to do with preserving the cultural/economic sanctuary we had created for ourselves and there was a sense of responsibility for your neighbors and loved ones.

I lived in a basement apartment and my father had a recording studio adjacent to it. My memories of home are closely tied to that apartment and all the musicians that came in and out of there. All of my friends have stories about playing some sort of instrument when coming over. Some have moved on to become great musicians. It wasn’t all easy but the good memories definitely outweigh the tough ones.

How has New York City influenced your art practice?

I think I was able to note the income disparities and ties to class and access as a kid – I always mention how train rides are intense meeting places for different folks across the spectrum of wealth, cultural backgrounds, you name it. When rush hour hits and the train is the fastest way across town, everyone is pushed to share space. This push and shove is something I think about a lot when in the studio – the chaos, the intimacy, the shared moments of humanity.

What are some of the main inspirations behind Mercado ?

Mercado came at a time when I was thinking about my place as an artist within the capitalist framework, art fairs, my aspirations, Latinx artists’ place in the global art economy… not being considered “American” enough or “Dominican” enough but refusing to be invisible, my own experience of the exchange of culture and goods between the two places. All of these ideas sort of jumbled in my head. I have so many tote bags filled with everything from a book on art criticism to magazines and lipstick – some things get lost in the mess and resurface when least expected. It felt like the perfect container for all these ideas.

How did the idea come about?

I started off making the Bodegon (Still-Life series) as a way to better understand the concepts that drive my practice. The objects went from being 2D to 3D and I knew that I was entering uncharted “sculptural” territory. My mother has been a part of my studio practice the last couple of years – I really came into sewing because of her. We made a small, life-size version of the object and she suggested we go bigger. Larry Ossei-Mensah, the curator of Mercado, had also suggested a larger scale. I was scared to go there but realized these things weren’t going to confront the viewer the way I intended unless I went big.

For your Red Bull House of Art Residency you have reimagined the Mercado series. Can you tell us a bit more about this?

I went back to the Bodegon pieces that had inspired the Mercado exhibition and isolated some of the objects – the plantain and pork rind chip bags – into the Racks, a play on the Donald Judd Stacks series, one of which I went to see at the Detroit Institute of Art. I worked with a Detroit artist and metal fabricator, Chris Turner, on the chip rack design and went to Michigan Sandblasting Inc. to get the final piece powder-coated. It was this great collaborative effort that really spoke to the conceptual ideas behind the work of the many hands and minds that work together to make a final product.

In these works you incorporate many classic NYC-centric items – such as the bodega bacon, egg, and cheese in one piece, and products such as green juice and Glossier lip balm in another. Can you talk a bit on the imagery included and how they interact with each other?

One of the ideas that seems to keep popping up while choosing images is how things are marketed to us and how we either conform to or subvert those tactics. For the most part the decision process is free associative, I let my mind wander. I look through notes I take on the subway, pictures, and screen grabs, and I try to bring them together in ways that feel like it could really be a specific person’s space. The rest is based on projections of ourselves in relation to those objects. The New York City-centric items speak to my upbringing and that of those around me, those objects have a real personal resonance. The Glossier and green juice are imagined nightstand objects that I associate with my studio assistant, really based on our conversations, her likes, and overall vibe.

What do you hope viewers take away from your work?

I’d like the take away to be that culture doesn’t exist in a vacuum, our lives are interconnected, there are all these ripple effects and moments we share. Although notions of “highbrow” and “lowbrow” are social constructs, that does not preclude their real world implications; perception has legs. I recently was part of a panel in which an audience member asked how to reach the intended viewer of the work – how can these insular conversations reach the communities we say are not attending these cultural institutions enough, and I responded something to the effect that if we include artists, such as myself, into these spaces, we bring with us our friends, family and communities. I love when young Dominican or New York Dominican viewers feel a connection to the objects, they see these little secrets hidden in the work. I don’t have answers but rather a jumbled mess of questions, and I hope the broader audience encounters the work and walks away with this same feeling.