“I could carry on doing amazing shows, getting lots of street cred. But it doesn’t put dinner on plates. Everyone has to grow up. I’m not Rod Stewart,” said Alexander McQueen speaking to i-D back in 2002. At the time, McQueen had recently sold 51% of his namesake brand to Gucci, in order to keep it financially afloat. Consequently, his time as creative director at the LVMH-owned Givenchy was now over, stepping quietly out the backdoor with two off-schedule presentations to buyers, rather than a final elaborate show.

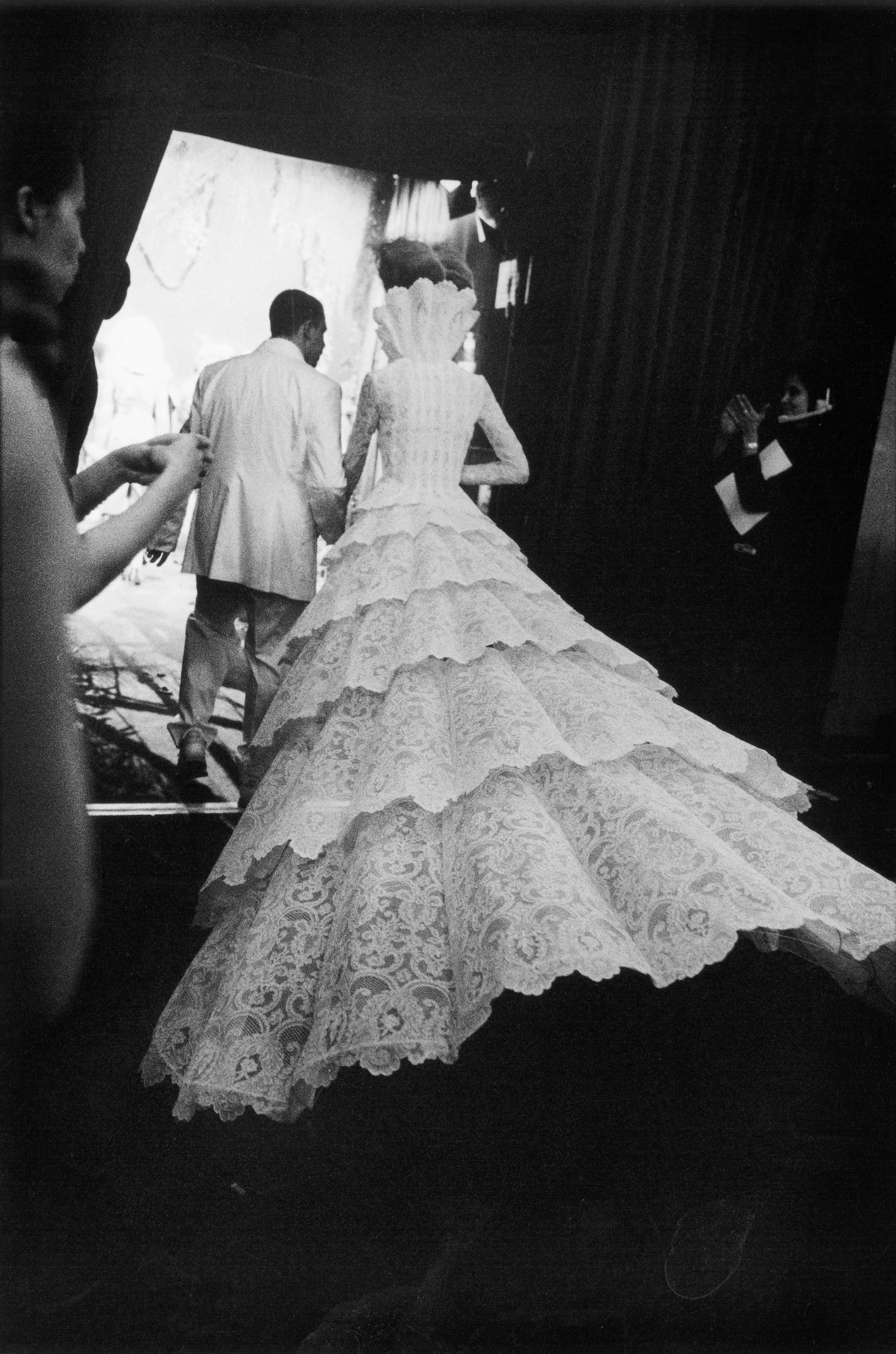

This conflict between creativity and commercial viability detailed in his i-D interview is a central pillar of Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui’s McQueen, the new documentary examining the titular designer’s ascent to glory, and descent into depression. Divided into six chapters, each pinned to an iconic collection of his, the film contextualises the unparalleled glamour of Lee’s designs within the often difficult climate in which the clothes were created and presented. From his graduate collection at CSM, to his appointment at the Givenchy couturier in Paris, to his final show, McQueen patches together handheld camera footage, TV interviews and interviews with those who knew him, to paint a picture of Lee’s career beyond the catwalk.

In emphasising the physical and mental strain of the business side of fashion, McQueen avoids dwelling on the usual tropes of working class to haute couture. The painful juxtaposition of grit and glamour that a talented young designer like Lee experienced is something that, two decades later, will resonate just as much with those forging a creative career in London. Amongst the extravagant archive footage of one of Lee’s most ambitious, celebrated collections — his infamous Highland Rape show — ex-boyfriend Andrew Groves remembers the pair eating McDonald’s afterwards, a meal they couldn’t afford to replace after dropping the tray on the floor. At a time when the financial reality of starting a brand in London couldn’t be harder, it’s a conflicting reality many know all too well.

As the film progresses, and the financial constraints that prohibited his earlier career are lifted by his appointment at Givenchy, the second wave of problems arises: the stress and exhaustion that comes with creating so many seasonal collections for a huge fashion house. In the perennial news cycle of ‘creative director steps down from top position at the industry’s biggest brand’, the narrative here also remains largely the same in 2018. From Raf to Riccardo, there are smalls signs of change, as creative directors begin to push back on the system. Yet we still attach a certain glamour to the idea of being overworked — an industry where “so stressed” acts as a marker of success. Seldom do we get to see behind-the-scenes realities of this, of the darkness brought on by this unforgiving system, as we do in McQueen.

The most literal embodiment of this feeling can be found in Chapter Four, a look at his spring/summer 01 collection, VOSS. The show took place within a giant mirrored box; one that at first reflected the audience back on themselves. As the two-way mirror switched, a set resembling a psychiatric ward was revealed. As the show ends, the walls of a smaller cubic structure in the centre of the glass box come crashing down. Inside lay Lee’s latest muse, fetish writer Michelle Olley, naked but for a breathing mask on her face, and hundreds of moths around her. The effect is powerful, sinister and a visceral representation of the state his mind was in.

But while McQueen celebrates Lee’s sheer creativity, wicked sense of humour, his empathy and his charm, the questions that it ultimately asks are: What happens when a highly talented individual suffers from a mental health problem? Is HIV+? And feels the weight of an entire company’s employees upon their shoulders? For as much as McQueen extols the talents of one of the most singular fashion visionaries of our generation, ultimately it lays bare how the fashion industry can eat up and spit out its most creative minds. What Lee accomplished was epic, but at the cost of his life. After all, as he himself says — ripping a Givenchy couture dress to create a slit down the back — “It’s just clothes.”