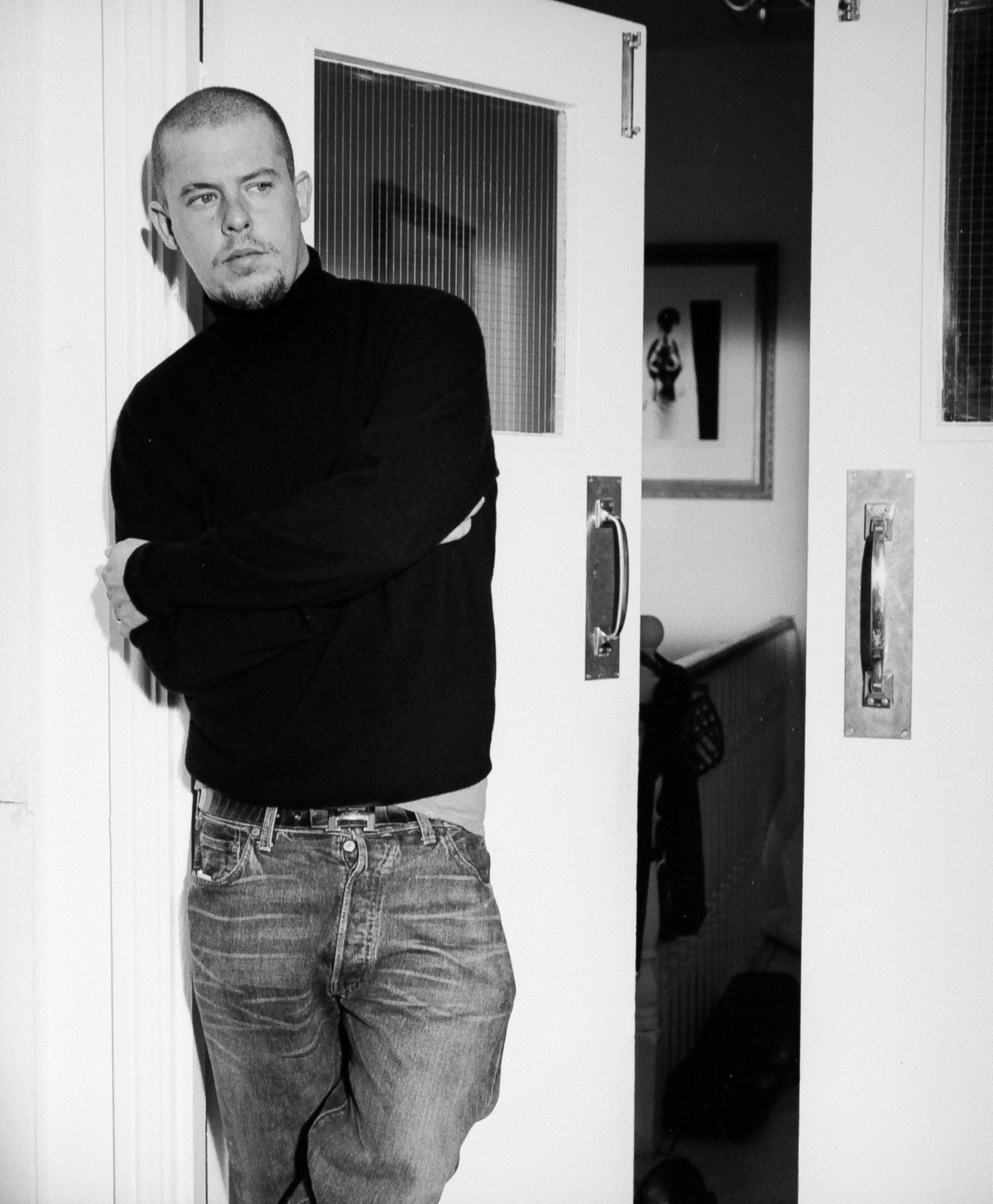

Creative people are supposed to be the least afraid of death. Artistic legacy, apparently, allows the author eternal life. It’s easier to go if you’ve left something behind. Since Alexander McQueen’s own death in 2010, his fascination with the afterlife has been the subject of our own morbid obsession, often obfuscating his life-affirming idiosyncrasies. The portrait of the legend offered in McQueen is as vivacious as it is tortured, revealing the unparalleled punk poet who defined youth culture in 90s post-Thatcher London. The image that stays with you after the credits roll is Lee as a pudgy East End kid dropping F-bombs in the atelier of Hubert de Givenchy, or shooting the shit with his soulmate Isabella “Issie” Blow.

“You can overdo the rags to riches thing — but that working class background is not normally where fashion designers come from,” explains writer Peter Ettedgui, whose father Joseph was one of McQueen’s first stockists. “It’s such an extraordinary journey to go from working class kid to, ten years later, the head of Givenchy.” McQueen also stood out for never dulling his anarchistic tendencies once he infiltrated fashion’s top ranks: impulsively wrapping one model in a discarded roll of bubble wrap and sending her down the runway; shattering a mirrored box inside his spring/summer 2001 “mental hospital” spectacular to reveal a nude plus-size model, writhing around in moths.

The supporting cast of McQueen is the designer’s closest friends and family members, including his sister Janet, stylist Mira Chai, Issie’s widower Detmar Blow, and assistant designer Sebastian Pons. Obviously it wasn’t easy to get everyone on board. “We had a lot of tears,” director Ian Bonhôte recalls. “People suddenly had to delve back into their emotional connection to those moments. We saw some moments that brought us to tears. Peter would be breaking up so I’d take over, or the other way around.” Ettedgui adds, “You’re not dealing with a story, you’re dealing with real lives.”

Their memories are interspersed with unseen archival footage of McQueen himself, and set to a swirling orchestral soundtrack by McQueen collaborator Michael Nyman. “Having orchestral music against these fashion shows lifted what was often quite a crappy archive into another zone,” Ettedgui explains.

i-D talked to Bonhôte and Ettedgui about creating their haunting film.

Why did you want to make a documentary about Alexander McQueen, and why was now the right time to do it?

Bonhôte: It was the right time because when we set up to get the financing, we managed to finance the film pretty quickly, so that meant there was a desire or hunger for a film about McQueen. We were aware that there were other projects about McQueen being floated, but we were not aware of a documentary. Lee’s anniversary of his passing is a year and a half away, but we didn’t set out to mark a date. Everything happened quite organically.

Ettedgui: I’d made a film a couple of years back about Marlon Brando. That was an extraordinary film to work on, so after that, I was hooked to the idea of working in this genre. But it’s very difficult to identify the right kind of personality or character who makes the film stand up, who can take you on a proper emotional journey. I grew up with a fashion background. My father was Joseph Ettedgui, the owner of the Joseph stores. He was one of the first retailers to buy McQueen’s very early collections.

Bonhôte: I always find it amazing that, after Galliano, Lee took over from Hubert de Givenchy. It was noble, upper-class French haute couture. John Galliano is working class but still flamboyant. Lee wasn’t. It’s really interesting that those French houses were opening up to creativity. They wanted to re-energize all those houses. It was the right time of energy.

What was your experience of London in the 90s like? Especially during the explosion of Cool Britannia , the period of increased U.K. pride that followed Labour’s landslide election victory?

Bonhôte: I came to London in September ‘97. Tony Blair just got elected, and people went to London — I’m half French, half Swiss — because there was this Cool Britannia. It was a very exciting time to be in London. I wouldn’t say Lee was right in the center of it, but he was among the central figures that were making London Cool Britannia. Lee collaborated with a lot of artists in music, in art, in photography — but he didn’t care if people were established. He just did stuff with people that inspired him. It was a time of crossover where art, music, fashion, imagery were just blending into one another. He was right in the middle of that.

Ettedgui: During that period, Ian was working at a very famous nightclub called the Blue Note in Hoxton. It was literally right opposite to where Lee and Mira were living. Mira said, “Oh, so you guys were responsible for keeping us up all night!”

Bonhôte: They came a lot to that club. They were hanging around there all the time.

What was your impression of him at that time?

Bonhôte: He was a chubby… [Laughs]. I think my memory of seeing him and seeing the work, there was such a contrast between the man and what he would produce. He had just got Givenchy at the time, and literally was the talk of the time. He was on the front of i-D, he was on the front of The Face, he was on the front of all the magazines born from the late 80s, early 90s. All those stylists and photographers at the time are now the establishment.

Ettedgui: I was shooting fashion shows for Joseph, while I was in school trying to get into film. It was interesting because the 80s had been such a beige time in London fashion. Suddenly, we had Galliano, McQueen, and Sensation, the huge exhibition at the Royal Academy that brought together Damien Hirst, the Chapman brothers, Tracy Emin. That’s all happening, and those connections are all happening, and they’re all feeding each other in a way.

Bonhôte: People were buying and consuming really creative art of all kinds. Suddenly the people with the money would realize, and would invest in that.

As you mentioned earlier, there are a few other projects about McQueen either wrapping or in the works. Why do you think he’s so present in our minds right now?

Ettedgui: You can’t get around the fact that, as a culture, we’re always attracted to the doomed artist as an archetype. A certain amount of Lee’s attraction to artists and writers is because of that. I hate saying it. We wanted to explore why he took his life at the peak of his powers and his success, but the story was how he got from the East End to Paris during that time. Those two questions — how he did it, and why he ended it there — those are very powerful questions for any dramatist or storyteller to look at. It’s also the fact that he was a rebel, and he was a provocateur, and he was a maverick. He’d got this incredible group of collaborators around him and they went on this incredible ride, sticking two fingers up to the establishment and revelling in it, and that’s fun. Then there’s the work. You have these spectacular visual fashion shows that are dramatic and are very different to anything that’s being done now.

We seem to have developed a taste for the opposite now, if you look at the reaction to Marc Jacobs’s silent Armory show .

Ettedgui: That’s my general sense. Whereas Lee was doing something that was raw. And autobiographical — it sounds weird to say that a fashion show is autobiographical, but it was with him.

Is that why you chose to present the film in five parts, with each represented by a different fashion show?

Bonhôte: We went through the shows and could see threads to his life. But Lee really shifted the way women dress. Lee wasn’t on point — he shifted the point. The bumster has been a joke, but within two or three years of the bumster, suddenly all the jeans companies brought down their waistbands. For five or ten years you couldn’t find jeans above a certain height. He did that as well with some of his silhouettes. Lee didn’t dress women for men to buy them clothes. He made clothes for women to dress the way they fucking want. He dressed a woman who was independent. The women in his life were strong women.

Ettedgui: We’re all interested in genius. It’s an overused word, but in his case, it holds true. He worked really, really hard at his craft. But he could take it in any direction he wanted. The number of stories we heard — he’d turn up with a roll of fabric and make you up with his eye. He’d have a pair of trousers for you within the hour.

There’s that scene where he’s backstage and sees a roll of bubble wrap. He puts a zip in it and sends it down the runway.

Ettedgui: There are very few people we meet in our lives who have that kind of quality.

Bonhôte: We were talking earlier about why the young generation adores him, and we love that first period in his life of improvising with anything he can find. There’s an amazing story in that. If you go to your fashion college, don’t think about spending money on the most expensive material. Think about the ideas and the concept. Use cotton you find in the street, or use your mother’s curtains while she’s looking away.

Ettedgui: That reminds me — he had some friends who owned this little patisserie café around the corner. Everyone from Central Saint Martins used to go there and have croissants in the morning, and they used to go clubbing in Soho on Saturday nights. Talia, one of the sisters who owned the café, told us that Lee was supposed to come over with fabric to make something for her to go clubbing in. He arrived on her doorstep, and she asked where the fabric was. He was like, “Oh, shit…. Don’t worry, we’ll find something.” He made a brilliant dress out of her bed cover.

Bonhôte: That was the happy times. Everything that happened in his life led to great things. People said, “You shouldn’t have gone to Givenchy, that was too much,” but maybe without Givenchy he wouldn’t have been able to afford to finance McQueen. But that early period of time, that chapter two, was a very inspiring time. Before some other forces come in.

Ettedgui: The story starts to darken. But there’s a certain innocence, and joy, and purity in those first two chapters.

Bonhôte: We always tried to bring back some light into those darker moments.