This article originally appeared in The Radical Issue, no. 351, Spring 2018.

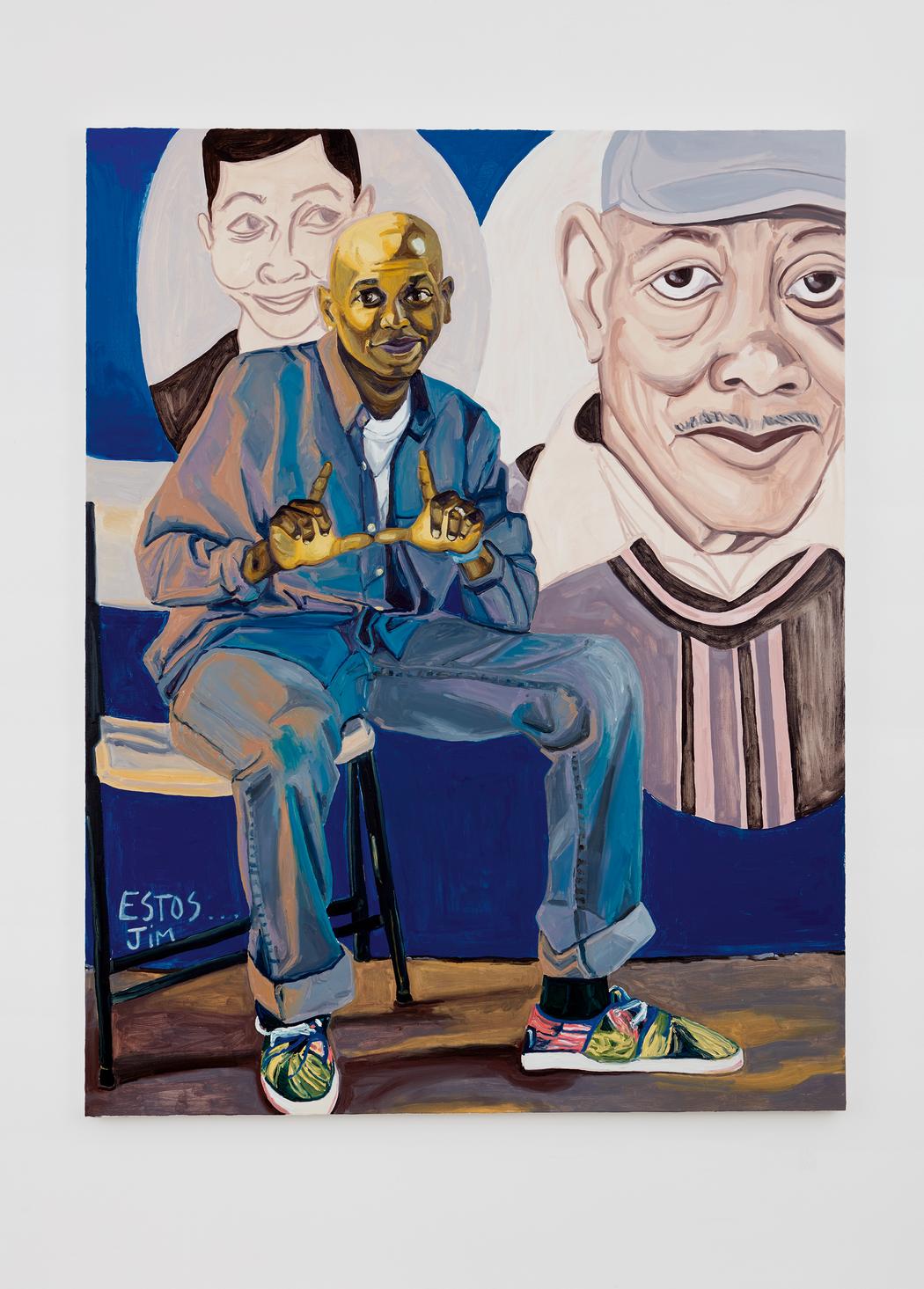

Black masculinity escapes concrete definition. You just know it when you see it. A distinctive fire in the eyes. A particular way of walking through life. A head held high. Last year Moonlight masterfully illustrated the dueling hardness and softness of black masculinity through its striking, neon-lit headshots. Jordan Casteel’s portraits operate in a similar vein, capturing her real-life subjects staring straight at the viewer and gifting us quick, personal glimpses into their inner worlds.

“The magic rests in the moment,” Jordan says about documenting black men in the sacred spaces of barbershops, bedrooms, and kitchens. “My intent is to highlight the magic of our existence as black bodies, and the physical spaces we occupy. I want to encourage viewers to slow down enough that they notice something they might not have before. Like, for example, someone’s humanity.”

The Denver-born artist spends her days shooting photos of black men hanging around her adopted neighbourhood of Harlem, and then transforms her favorites into warm, oversaturated paintings. The scenes she captures are instantly recognizable: a young man chilling on the steps of his apartment building, an older gentlemen dressed in Sunday best and rocking a suave brown fedora. Two boys, both wearing slides with socks, sitting on a twin bed and holding a basketball. “I can spend weeks just walking around Harlem, and sometimes it’ll be days until I meet my next subject,” Jordan says, sharing her creative process. “Other times, I can find three subjects in a matter of hours. I’ll take up to 100 photographs in ten to 15 minutes, hoping to capture the essence of the person and their environment.”

Jordan is fiercely protective of her subjects. In her nude portraits — her subjects’ skin colored psychedelic hues of emerald, plum, and crimson — she makes a conscious decision not to show genitalia. Black men have been, and continue to be, fetishized by the white gaze. The omission is a meaningful one. It keeps our focus on the vulnerability these men are showing us. In the beginning of her career, Jordan experienced some resistance from critics for this choice. But she stood her ground.

“I feel an immense amount of responsibility toward my subjects,” she says. “They’ve given me permission to translate their image and then share it with a wider audience. So it’s imperative that everyone who took the time to share themselves with me is respected.”

Jordan has made a name for herself in the art world with incredible speed. She obtained an MFA from Yale (her classmates included fellow black artists Awol Erizku, Brandon Cox, and Samantha Vernon) and then in 2015 became an artist in residence at The Studio Museum in Harlem, receiving funding and support from the black institution. (“Harlem was immediately a breath of fresh air. I felt like there was room for me.”) And now, Jordan is busy teaching painting at Rutgers University and staging solo exhibitions across New York.

Despite her critical success, Jordan feels the world has been too focused on her and not her work. Often, people of color are expected to talk about their feelings of disenfranchisement over and over again. But at this point in her career, Jordan wants her technical craft to receive equal attention. “It’s not uncommon for a historically marginalized artist’s biography to rise to the forefront,” she says. “However, I am noticing that the biographical take is increasingly common for me. Don’t get me wrong — my past very much informs my present and the work I choose to make — but it does seem to be a focus.”

Jordan paints with intuition. She starts each work by laying out color swatches and immediately picking up whichever shades she’s drawn to. “I sort through, pick up, and put down colors until I get to a place that feels right,” she says. “I suppose it’s an almost unconscious decision.” She says she paints her subjects’ skin in a variety of sherbet hues to “push the boundaries of expression” when it comes to bodies of color. For example, highlighting the range of shades that can exist in a single family. And for her recent exhibition at Casey Kaplan Gallery in New York, Jordan captured men during the nighttime — lit by amber street lights and glowing smartphones — to create a sense of depth and interaction with viewers. In America, black men walking around at night are unjustly perceived to be dangerous. It feels refreshing to see their softness in darkness.

Jordan’s talent for extracting the emotionality of black men deserves as much attention as her biography. Because only an artist deeply familiar with her subjects, and community, can accomplish that. “I hope 2018 brings balance,” Jordan tells i-D, speaking about what she wants to accomplish this year. “The past few years have been such a whirlwind, and I think it’s so important to practice self-care.” Jordan commonly paints her subjects in moments of deep introspection, and now she is planning to do some herself. “I think through self-reflection, celebration and rest, the work will be given room to manifest itself in exciting ways I can’t predict,” she says. “Maintaining the space, and time, to take risks and fail is priceless.”

Credits

Photography Zora Sicher

Styling Lana Jay Lackey

Makeup Marcelo Gutierrez. Styling assistance Carlos Acevedo.