When Ed Templeton discovered skateboarding as a middle schooler in the mid-1980s, being part of one subcultural youth tribe unexpectedly granted him entrée into another: the punk scene.

“Just having a skateboard gave me access to these kids that, up until that point, I would avoid. They looked badass, but they scared the hell out of me,” Templeton tells me of Huntington Beach’s punk contingent. “Suddenly, they were like, ‘You skate, right? Come hang out with us.’ It opened up a whole new world. They started giving me tapes of stuff like Dead Kennedys. I started skateboarding a lot more. I remember being taken under a wing by these punk kids, and it all went from there.”

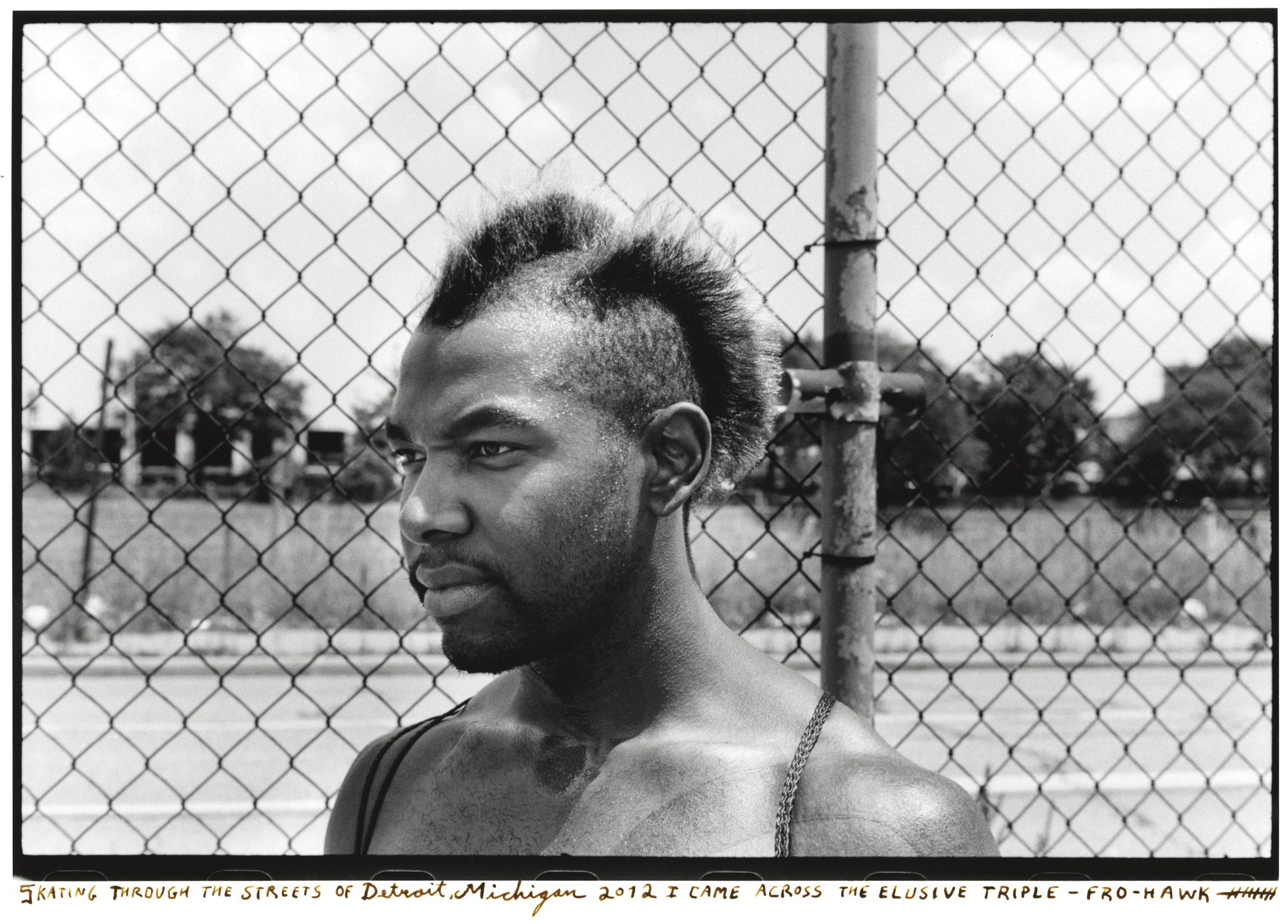

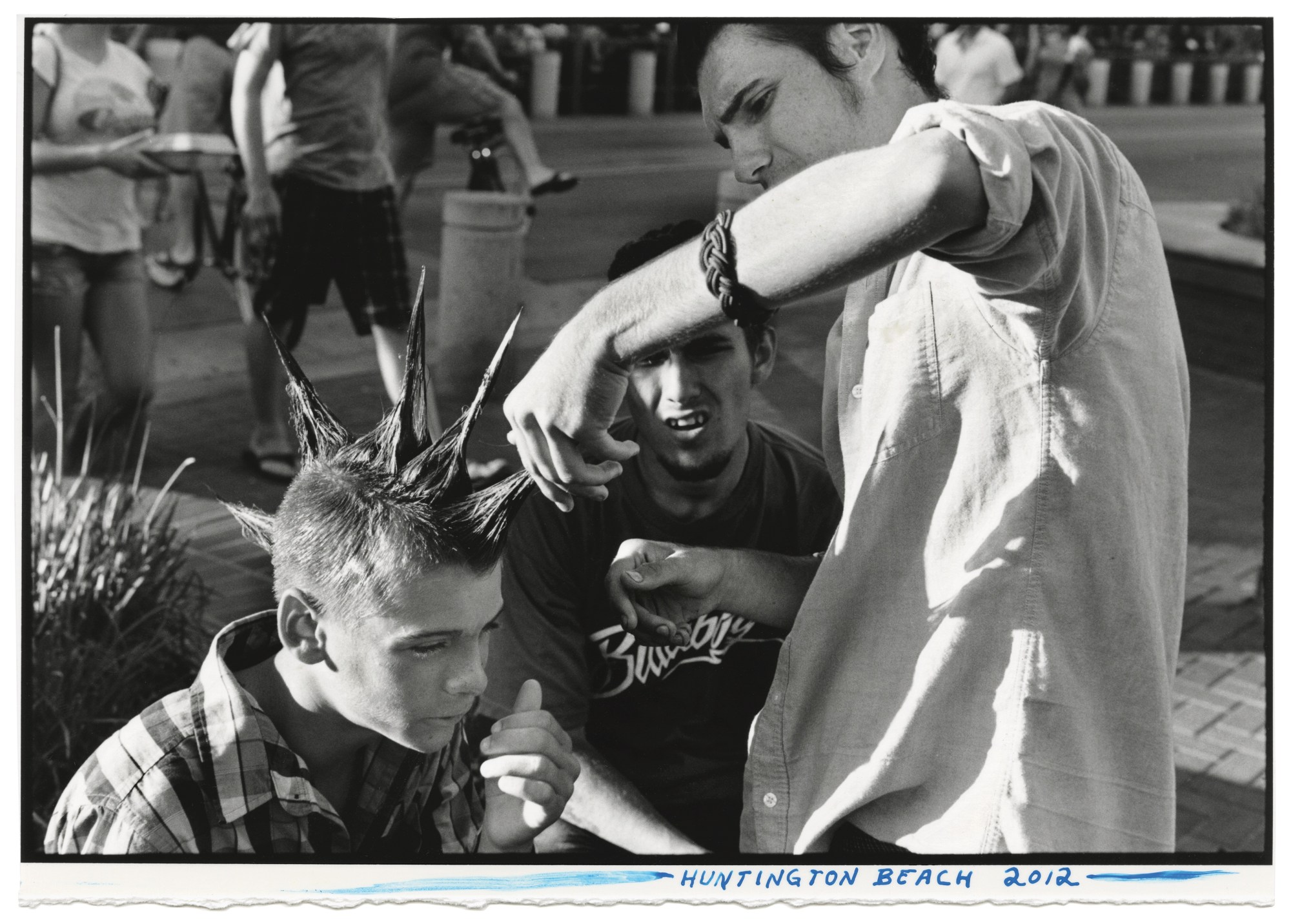

In the press release of his new exhibition, Hairdos of Defiance, Templeton recalls a morning where one of his teenage punk pals, Ron Hanstein, walked into Ethel Dwyer Middle School with his otherwise shaggy mohawk fully spiked. “I asked him how he got it so rigid and he told me, ‘egg whites and Knox gelatin.’ Later that day he was kicked out of school for it.”

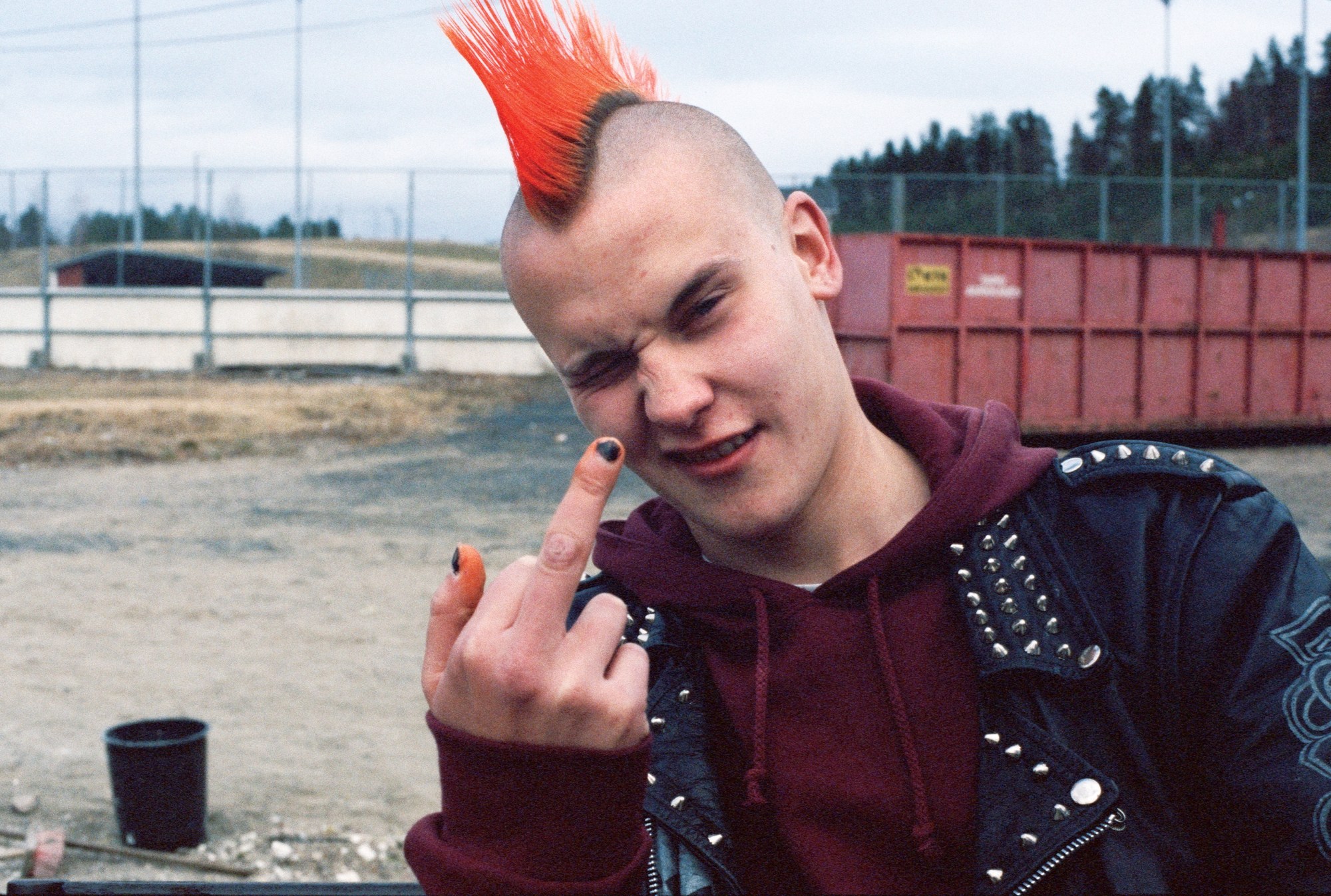

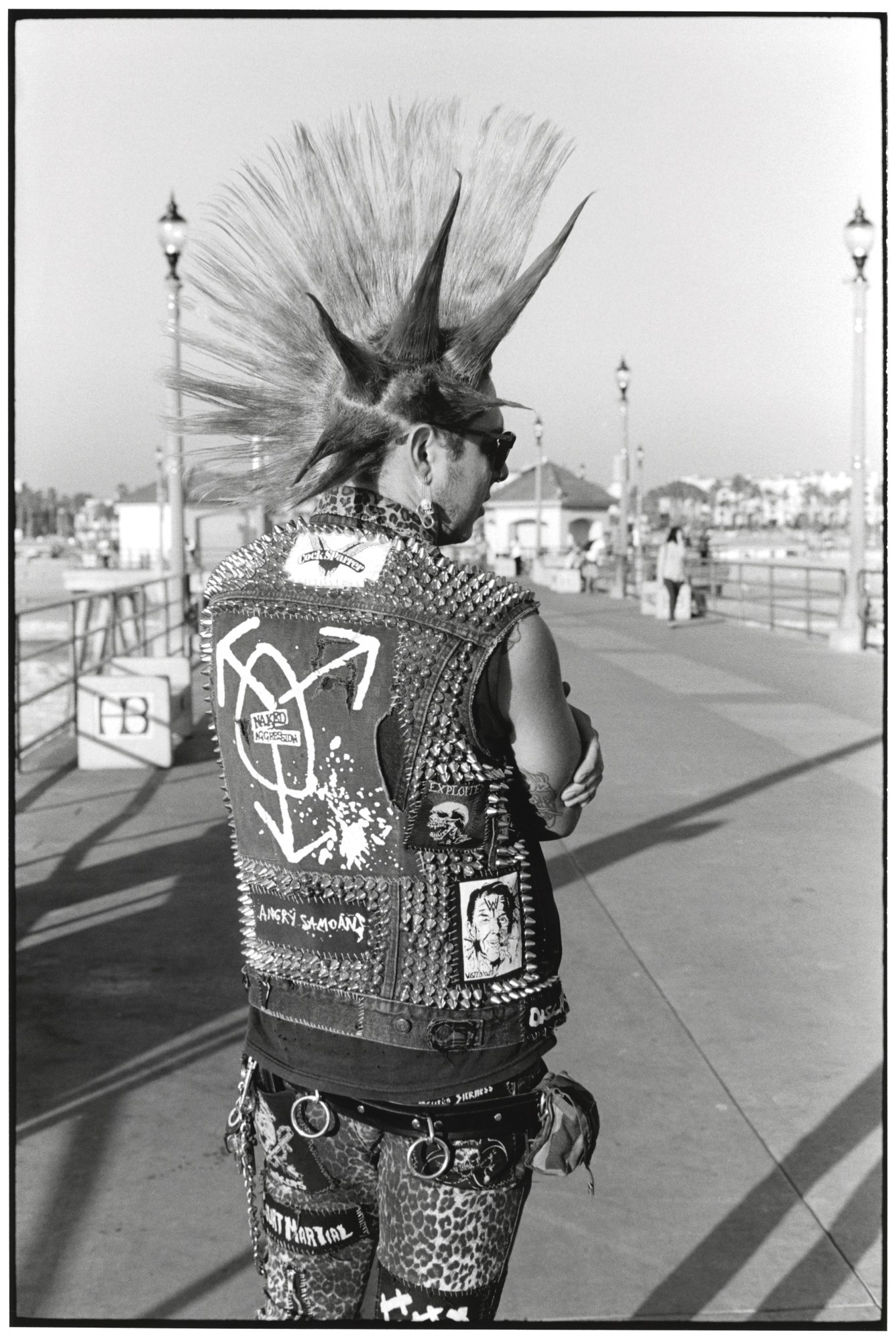

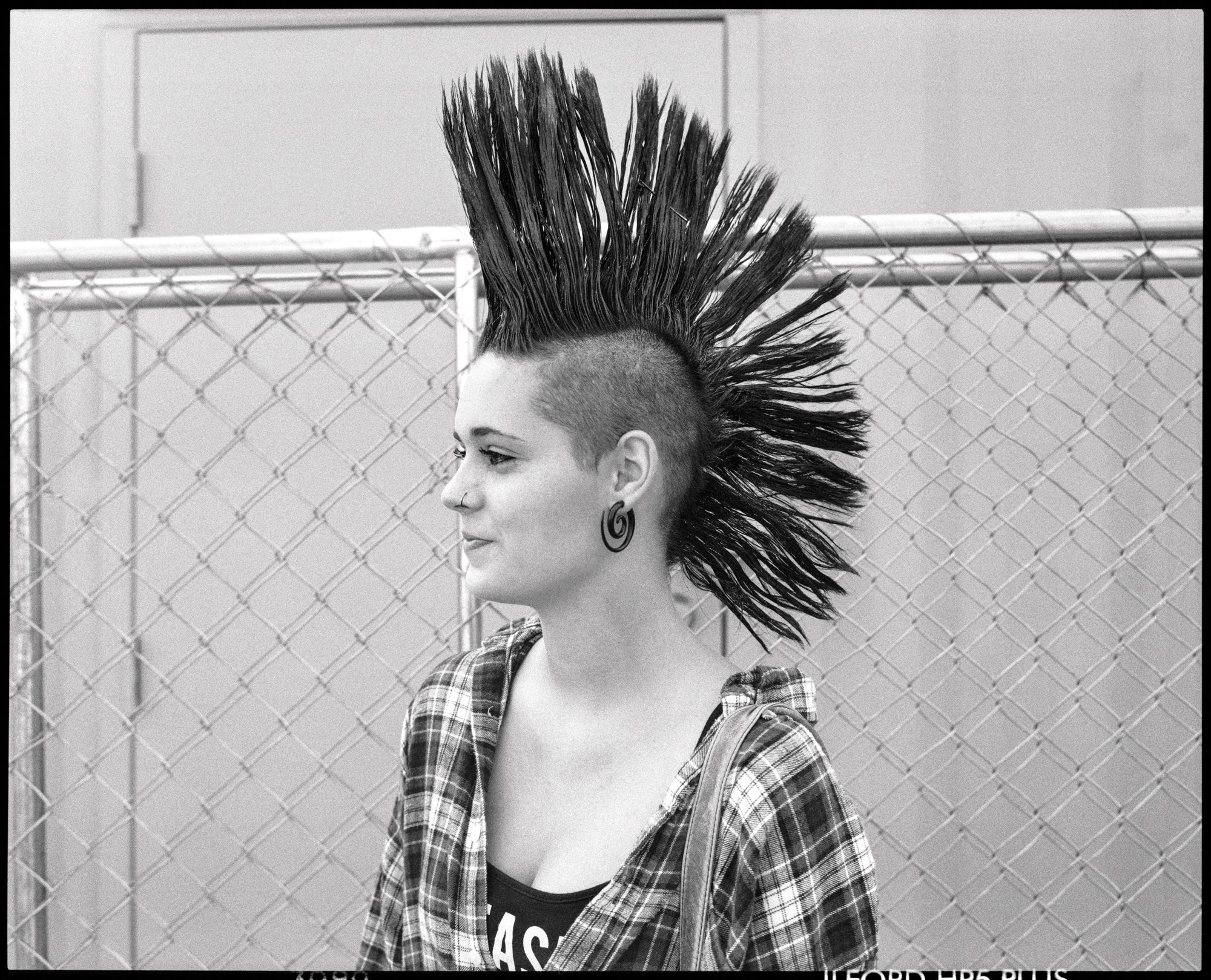

Similar to the way Templeton’s much-loved projects Teenage Smokers and Teenage Kissers focused exclusively on adolescent cigarette puffers and sloppy-yet-self-assured makeouts, Hairdos of Defiance is a collection of strictly mohawk pictures. These portraits of follicular rebellion were made over the past two decades, during Templeton’s daily trips to the Huntington Beach Pier, as well as his travels around the world. Like all of his best photographs, they capture everyday eccentricities with a mix of humor and empathy.

Ahead of the show’s opening tomorrow evening at Roberts Projects in Los Angeles, Templeton tells us why he’d never rock a ‘hawk (but admires those who do).

Why a show of mohawk pictures?

The name came first. My friend Mike Burnett is a photographer for Thrasher magazine. We go on skate tours together all the time. Once, we saw some kids with mohawks. Mike said, “Look at those, hairdos of defiance.” I just loved the way he delivered it, and I’ve always remembered that term, “hairdos of defiance.” So every time I saw someone with a mohawk, I thought, ‘There’s a hairdo of defiance.’ When Roberts Projects approached me about doing a show in their project room, I started thinking about what I could put in there, and that name popped into my head. I began looking through my archive and realized that, over the years, I’d gravitated towards kids with mohawks. If I saw them on the street, I’d talk to them, or pull them aside and get a portrait. I don’t think I ever imagined I’d collect it as a series, it’s just something I did as I’d be shooting around in the street.

Many of your street photographs were made with an approach that’s more covert, spontaneous, and situational. But these kids seem to know you’re photographing them.

Generally, I’m not overtly brave. I have my methods that get me close to people, but usually I don’t try to engage in conversation because I’m not the greatest with banter. There are a few [mohawk pictures] that were taken on the fly, but yeah, for the most part, it’s hard to get a good photo of a mohawk unless you have someone standing still. So if I saw someone that had a particularly cool one, I’d go up and ask them for a photo. In doing that, I realized that I’m coming from a generation where a mohawk was something to be scared of. In 1985, when I started skateboarding and listening to punk music, a mohawk meant “Leave me the fuck alone.” But now, in the 2000s, a mohawk is almost like, “Hey, check me out,” you know? When I approached these kids, some of them looked a little scary, but I realized they want to be photographed — they love it. That’s why they spent all this time fixing their hair up. I found most people were more than happy to have their photo taken. After a while, I got more brave.

In the show’s release, you talk about your friend who got kicked out of school for his mohawk. It makes “hairdos of defiance” ring so true. Agitating authority so much that they’d kick you out, without even saying a word.

Sure, mohawks have held that meaning forever. Native American tribes wore mohawks to intimidate people when going into battle. There was a battalion of U.S. paratroopers in World War II that shaved mohawks to make themselves look crazy. When the punks in the 70s in London started adopting them, it was the ultimate antisocial behavior. An eyesore, a fuck you. It’s always been a haircut that’s meant to be antagonistic.

How did you go about selecting the photographs for the show?

A major project has been trying to digitize my entire archive. Everything I do is on film, so I’ve been scanning all the proof sheets and putting tags on everything. It’s pretty close to being completely digitally archived to the point where I’m able to search for the word “mohawk” and find photos from as far back as 1998. A lot of my projects come after the fact. I don’t set out to shoot any series. And because of that, I think there’s more depth. Sometimes people conceive of a project idea, and they do it for maybe two years. It might be great, but it’s only two years of work. This goes back decades. Once I collected all the photos I’d tagged “mohawk,” or “crazy haircut,” I just picked the best ones. Some weren’t as sharp, or I didn’t really capture the moment. Some mohawks were just cooler than others.

Did you photograph anyone repeatedly over the years?

There’s a guy in Huntington Beach who wears a mohawk, and he sometimes lays out on the beach reading books with it fully spiked up. I’ve shot him a bunch of times over the years without even realizing it was the same guy. I think he ends up in the book twice. There’s also a guy with green Liberty spikes I’ve seen a bunch of times. He’s in the book twice, too.

You and Deanna walk around London a ton when you’re there. Have you noticed any regional differences in mohawks?

I hadn’t really thought about it until you asked, but in London, I see very clean mohawks. There’s two in London I can recall off the top of my head, and both were really immaculate. Super combed, almost space-age. Here in California, they’re sort of ragged. You can tell they sort of pushed it together with their hands.

Tell me about the installation component of this show.

Generally, I try to make my exhibitions a little more homey if I can. I paint walls blue or green — colors that someone might use in their house. Just to have something different than a sterile white wall. Last year, I did a show in Japan in this surf shop. There was a sort of plywood component where I was hanging unframed prints. I remember thinking how cool that looked. So when this show came along, I wanted to try something similar. The project room at Roberts is a smaller room on the side of the main gallery that feels more intimate. We’re putting wood paneling around the space, and most of the prints are unframed. I ripped the edges off some of the prints, so there’s a bit of roughness to things as well. I painted on some of the photographs and wrote on a lot of them. The plan is to pin them up haphazardly, so that it’ll look sort of like some weird garage, or like someone’s room with things tacked up all over the place. Makes it a little more informal, and punk in a way.

Have you ever done anything crazy with your hair?

No, and part of the reason I think I’m attracted to these kids that do this is that it’s something I could never do personally. There’s two reasons why: one is that my perception of punk was the opposite of putting a mohawk up. The idea that you’d spend an hour fixing your hair up, working on a meticulous look to be punk kind of didn’t make sense to me. I come from the Fugazi side where it’s more about dressing plainly, and not spending a lot of time thinking about your hair. But on the other side, I don’t think I have the bravery to do it! I’m kind of in awe that people walk out of the house and interact with society on a daily basis with that haircut. I’m in awe of them as much as I don’t want to, or couldn’t do it myself.

Ed Templeton, ‘Hairdos of Defiance’ is on view at Roberts Projects from March 17 – April 21, 2018. An accompanying catalog , published by Deadbeat Club, contains an essay written by Templeton. More information here.