This article originally appeared in The Radical Issue, no. 351, Spring 2018.

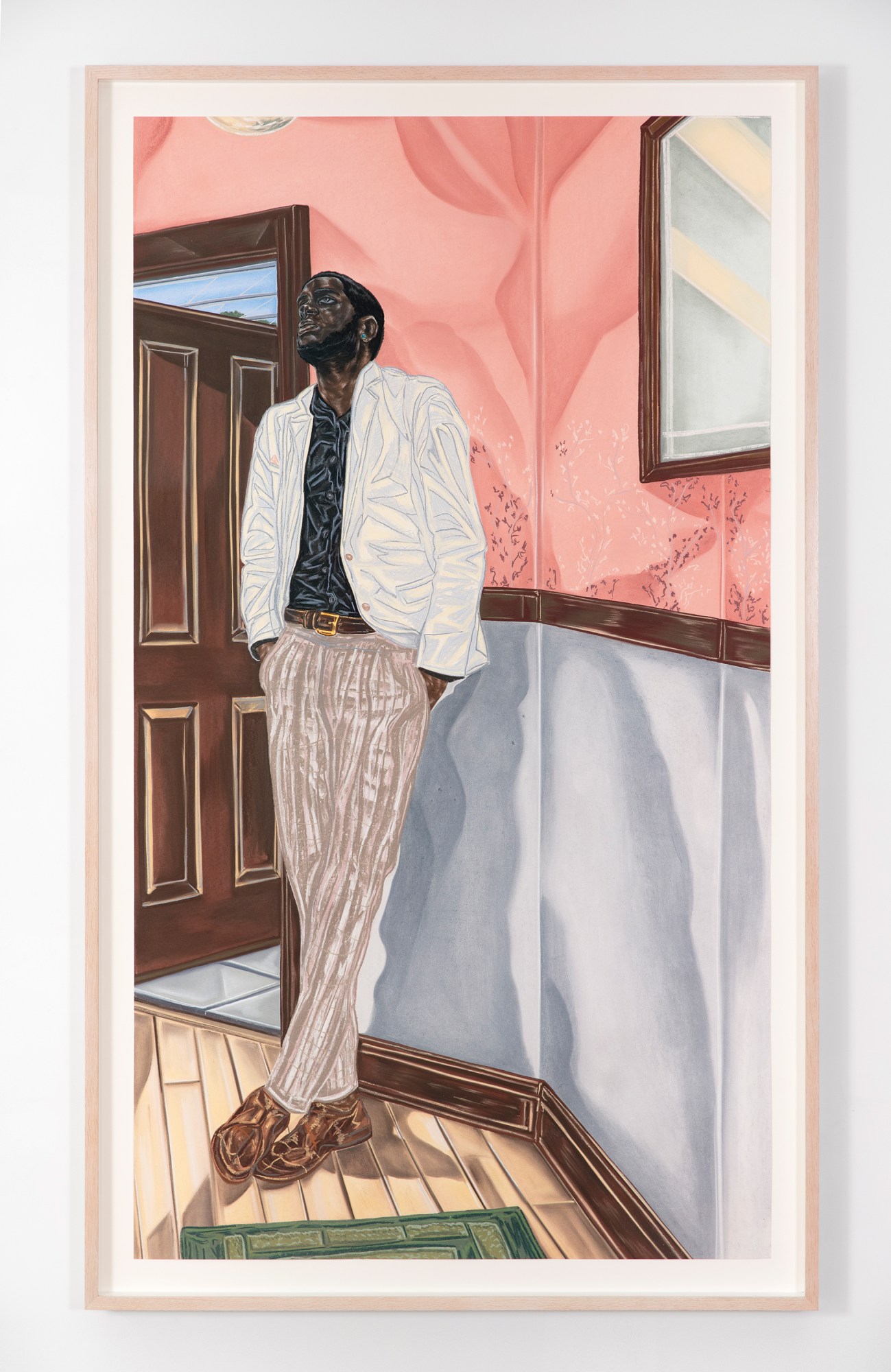

Toyin Ojih Odutola is taking in the radically soft, life-sized portraits of a fictional aristocratic family she’s created. These mothers, fathers and sisters are visions of black excellence — wearing gentle pastels, sheer fabrics, and thigh-high go-go boots — and they live in a lush Nigeria where the past and present are indistinguishable from each other. “It’s almost like we don’t get the right to imagine what black wealth looked like,” the Nigeria-born, America-raised artist begins. She looks at her character’s chiffon shirts with a sense of longing. “For me, it’s tricky. With Afrofuturism, we always say the future is going to get better. But what if all of these things we’re imagining have happened?” Toyin points to a painting of her protagonists embracing each other. The two dark-skinned men seem uninhibited, despite being fictional royals of a country with very real anti-gay laws. It feels like a piece of magical realism: Toyin imagining a Nigeria in which queer love is free of stigma. But it’s not, she says. The painting is rooted in the past, not the future. It’s a reminder that queer love stories have flowered in Nigeria for centuries, and will continue to flourish. “If you want to claim Nigeria, then you have to claim them. You can’t separate the two,” the artist says.

When we talk, Toyin’s exhibition at the Whitney Museum, To Wander Determined, is nearing the end of its four-month run. Staging her first solo exhibition in NYC – and at the same museum that houses work by modern greats such as Edward Hopper and Elizabeth Murray – was a big deal for the artist. Toyin put the show together in just a few months, after the Whitney approached her. “At first I was like, ‘I’ve done this before, but I’m a little older and have a crick in my back,’” she jokes, her laugh bouncing off the walls before she turns serious. “But I knew this was important because of the institution and how it positions my work in the space.”

Toyin has been making her mark on pop culture for years now. Solange is a long-time collector, poet Claudia Rankine wrote an in-depth essay about her work, and one of her chalk-drawn portraits appeared in an episode of Empire (hanging in Cookie Lyon’s living room). She first became famous for highlighting the shimmer and magic of black skin with her intricate ink pen and chalk dots that, in her words, “break the skin up into facets”. But her portraits of this fictional family on display at the Whitney seem to suggest a new focus: highlighting the shimmer and magic of black lives.

Toyin says this was the driving question for her Whitney exhibition: What if you claimed everywhere you go as a home? Some black people avoid travelling because they (reasonably) fear they’ll encounter racism. Toyin wanted to help ease this hesitation by depicting black people outside, in nature, swimming in lagoons, chilling on the beach, taking in the sunset.

“I wanted to tackle a family that was out in the world,” she says, frustrated by the lack of representation in art and pop culture. “So much black imagery is about this idea that black families only in exist in certain hubs like Chicago and Harlem. And you find these old Jet magazines where black people are like, ‘Okay, we’re gonna go on a little trip, but it’s going to be tricky!’ Never going into unknown territories, or, if you do, feeling like you should be afraid from the onset.”

Toyin’s latest portraits illustrate a non-performative blackness. Her subjects are captured in states of leisure and, therefore, let us see their most unbothered selves. It’s the black body safe from the slew of day-to-day microaggressions. “It can be in an office space or on the subway, but someone can just shift when you sit down and that triggers something,” Toyin reflects. “It’s really hard to describe that for other people. So, for once, I wanted to see figures that – and I know this phrase is misused a lot – just happen to be black.” Toyin doesn’t want her paintings to simply provide us with new forms of representation; she wants them to suggest new ways of existing.

Toyin is quietly getting ready for her next exhibition. This one will also explore the lives of her complex, liberated and elegant characters. But after that she’ll take a break from them. “I’ve been too deep into it,” she jokes, reflecting on the time she’s spent writing out detailed narratives for these fictional subjects (Toyin, a self-described fangirl, says graphic novels and comic books inspired her creative process).

“Really, at the end of the day, you’re walking through a show about two gay men and their lives,” Toyin says, a pleased smile spreading across her face. “A lot of people don’t realise it, because you’re not just seeing them. It’s their aunts, their mothers, their fathers. These two men are entrenched in the Nigerian community. You can’t extract them from it.” It feels like that’s exactly the point that Toyin is trying to make: every life touches another. Therefore – white or black, gay or straight – we must own the spaces we enter, travel the world, and embrace each other.

Credits

Photography Tyler Mitchell

Styling Jason Rider

Make-up Yui Ishibashi. Set design Lauren Nikrooz. Photography assistance Owen Smith-Clark. Styling assistance Jeremy Anderegg. Set design assistance Alvin Manalo.