For a brief, shining moment, Mark Morrisroe (1959–1989) transformed the landscape of photography and performance art, carving a singular path through the American avant-garde. While his biography is the stuff of a Ryan Murphy limited series, Mark didn’t let circumstance define his life; instead, he practiced alchemy, using it as raw fuel to create a space where he could explore tender feelings of love, longing, and loss.

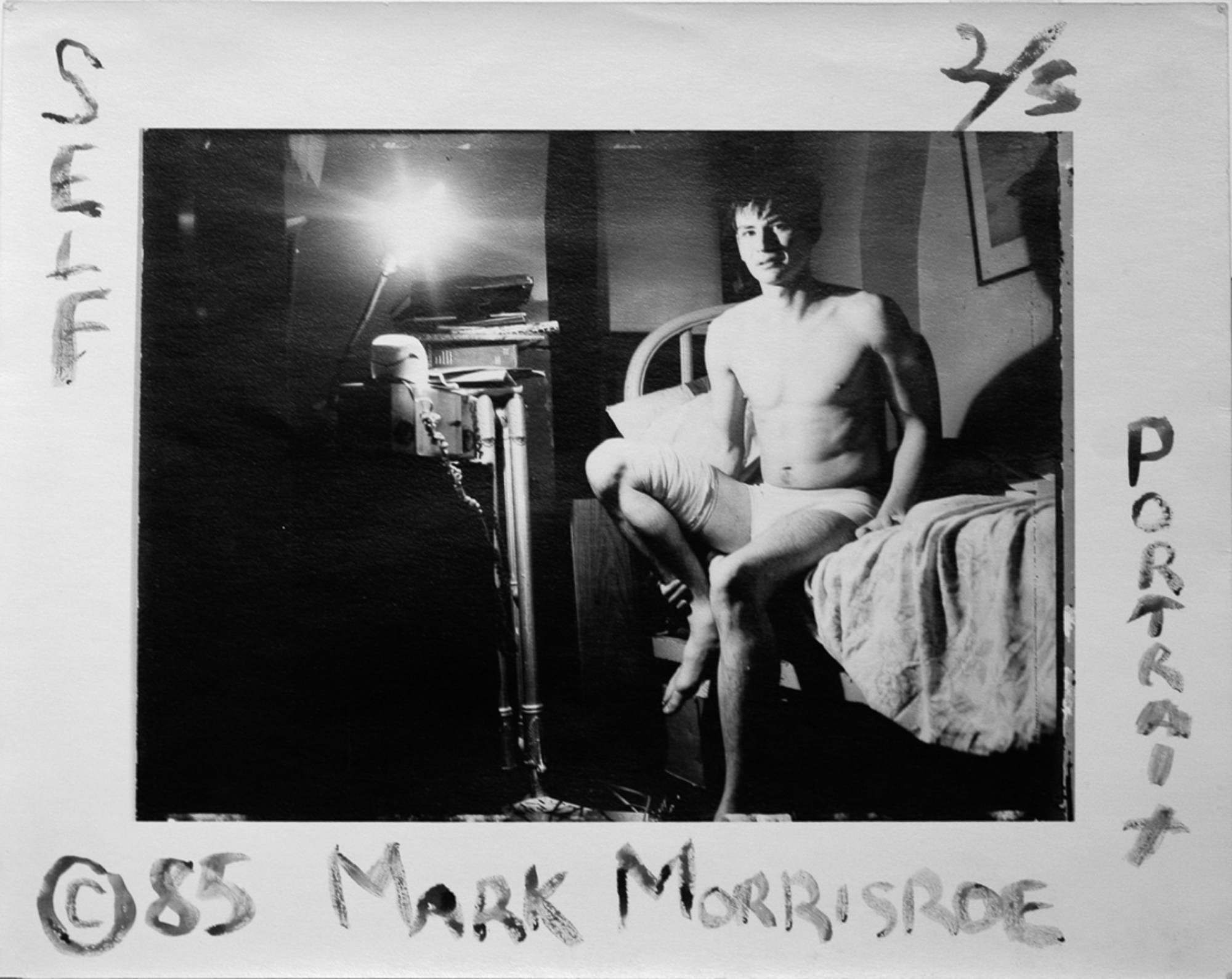

“It kills me to look at my old photographs of myself and my friends,” Mark revealed in the landmark 1999 Twin Palms monograph. “We were such beautiful, sexy kids but we always felt bad because we thought we were ugly at the time. It was because we were such outcasts in high school and so unpopular. We believed what other people said. If any one of us could have seen how attractive we really were we might have made something better of our lives.”

Long before conversations on trauma, drug addiction, sex work and gun violence were a part of the public discourse, Mark spoke openly about his harrowing past growing up just five miles north of Boston. “Mark liked telling the details of his childhood,” says gallerist Brian Clamp, who will be exhibiting Mark’s work at the Clamp booth during The Photography Show in New York from March 31–April 2, 2023.

Born to a single mother struggling with alcohol and drug dependency, Mark kept a crumpled photograph of Albert de Salvo, aka “The Boston Strangler” pinned to the wall of his childhood bedroom, imagining that Albert — who just so happened to his mother’s close neighbor and landlord at the time Mark was conceived — was his biological father.

Burning with unanswered questions about his identity, Mark’s fascination with persona, performance, and photography began to take shape, forging inextricable connections between his life and art. “Mark was an outlaw on every front—sexually, socially, and artistically. He was marked by his dramatic and violent adolescence as a teenage prostitute with a deep distrust and a fierce sense of his uniqueness,” Nan Goldin said in 1993.

At age 13, Mark began hustling to support himself; a few years later a disgruntled client shot him in the chest. The bullet lodged too close to his spine to be removed, causing him to walk with a severe limp for the remainder of his life.

“It also influenced his art. Mark did some chest X-ray prints where you can actually see the bullet, so you see his biography lacing in and out of the work,” says Brian. “Mark was a rebel. He had a big personality and he liked making people feel uncomfortable, not only with his behavior but also with his artwork.”

With sex, disability, survival and death intertwined from a young age, Mark cultivated personae he could embody and perform. In 1975, he and high school friend Lynelle White started publishing Dirt, a hand-colored zine filled with celebrity gossip and fanfic they peddled at underground nightclubs across Boston.

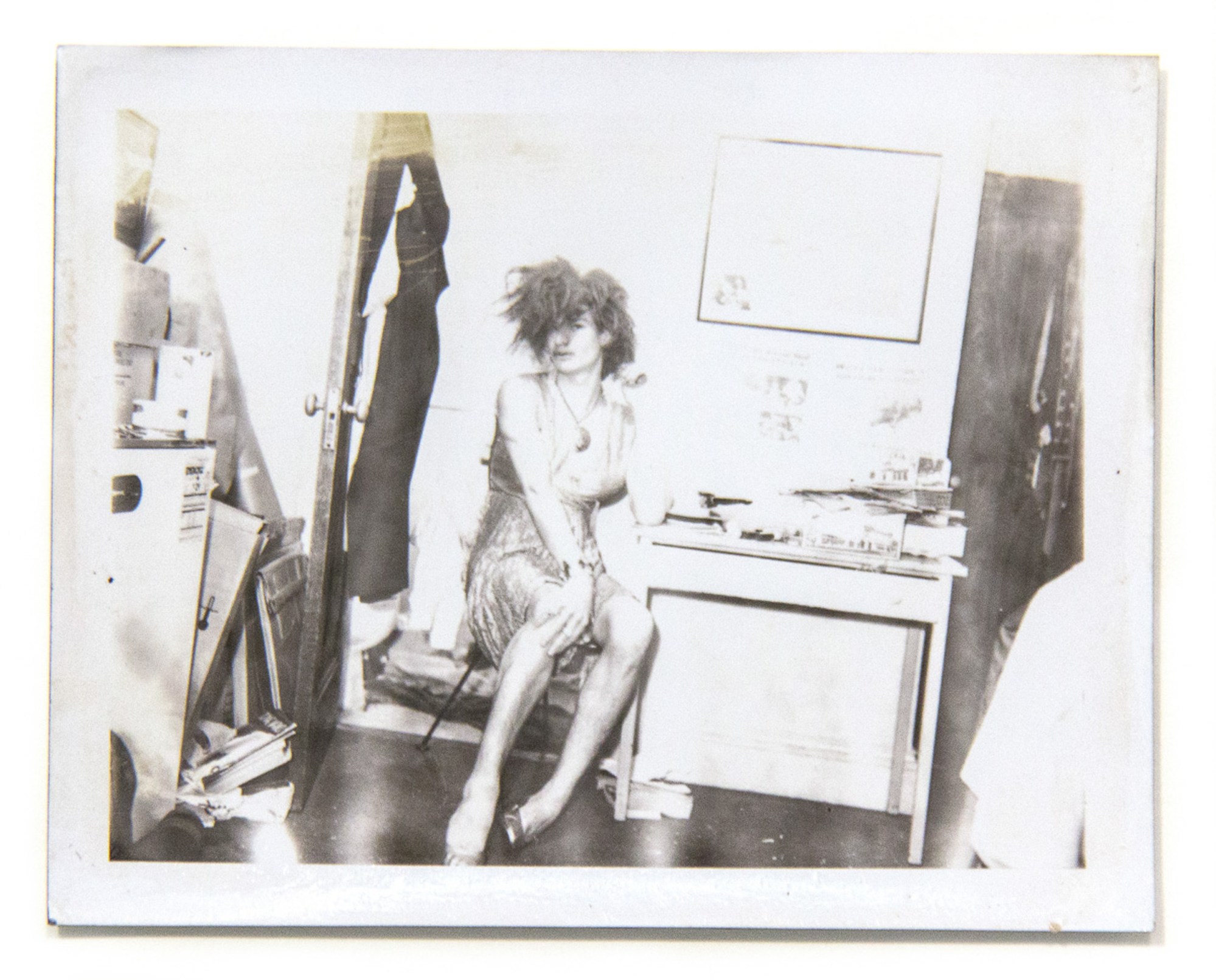

At the time, the Boston School was coming into its own as a new generation of artists, performers, and photographers arrived on the scene. After enrolling in the prestigious School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Mark was firmly in the mix, developing friendships with soon-to-be-art-stars like Jack Pierson, Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Stephen Tashjian (aka Tabboo!), Gail Thacker, Pat Hearn and Doug and Mike Starn.

“I met him in Art School in 1977; he left shit in my mailbox as a gesture of friendship,” Nan Goldin said in 1993. “Limping wildly down the halls in his torn t-shirts, calling himself Mark Dirt, he was Boston’s first punk. He developed into a photographer with a completely distinctive artistic vision and signature. Both his pictures of his lovers, close friends, and objects of desire, and his touching stilllifes of rooms, dead flowers, and dream images stand as timeless fragments of his life, resonating with sexual longing, loneliness, and loss.”

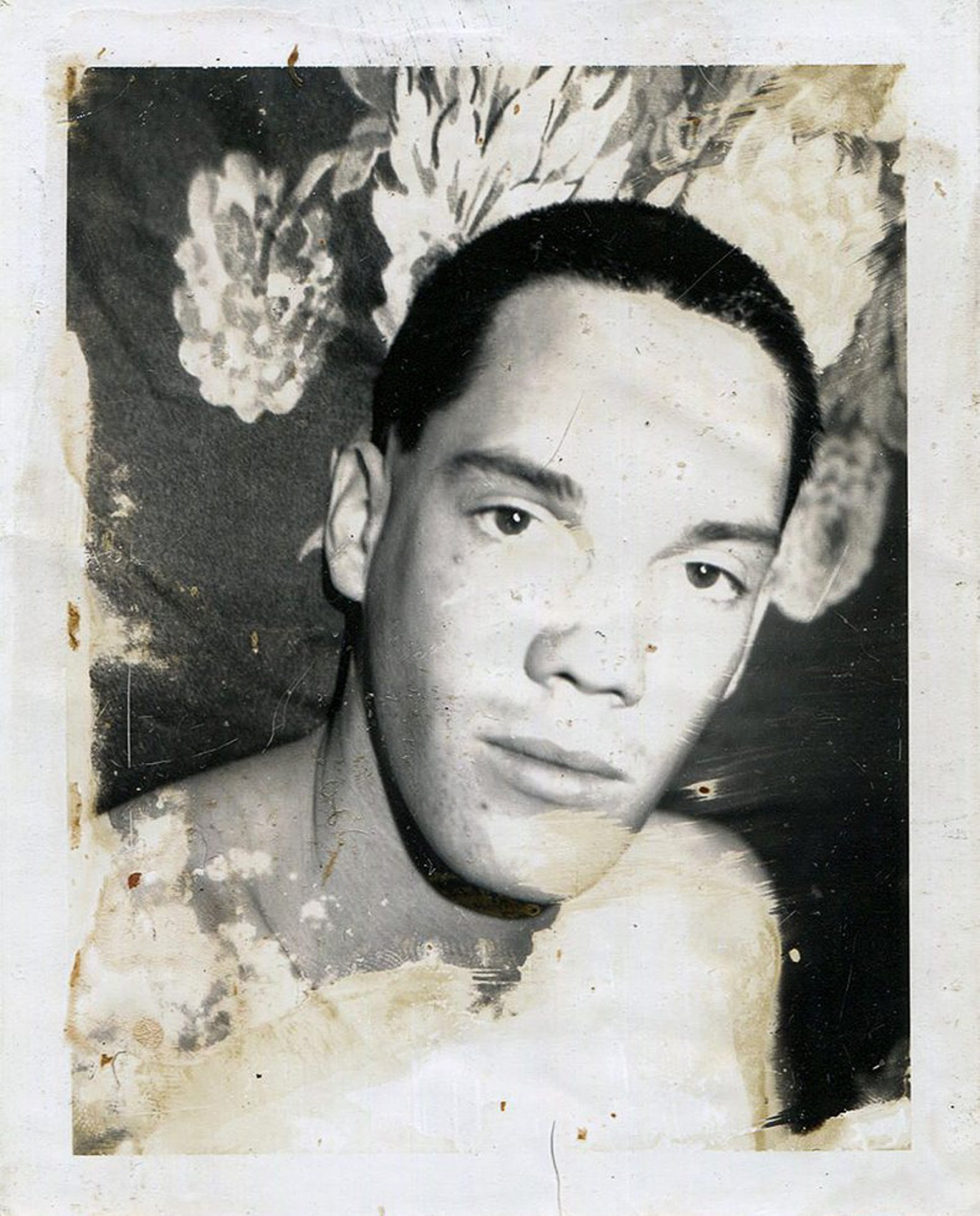

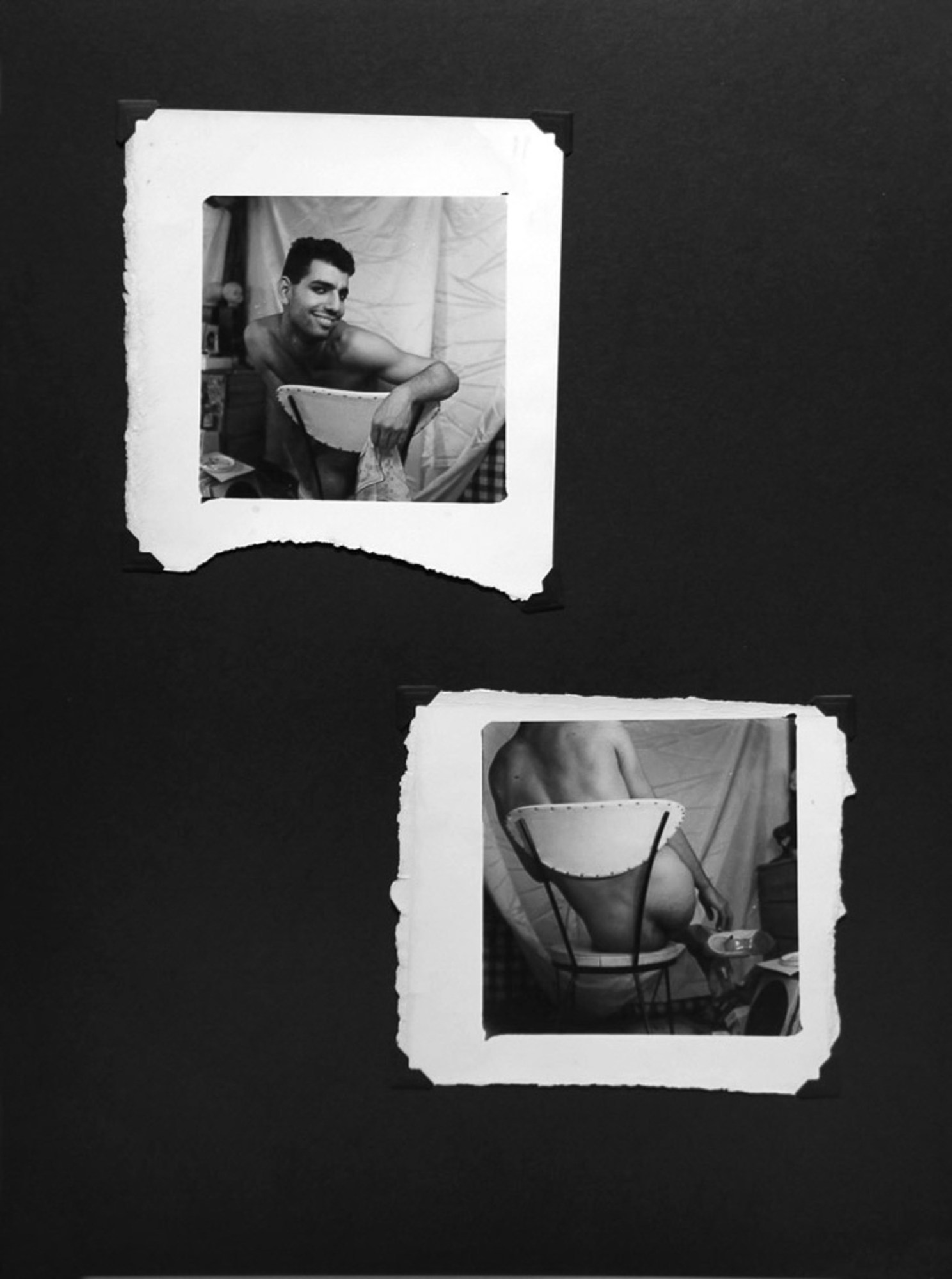

For Mark, the Polaroid 195 Land Camera was the medium of choice, given the ways in which he could manipulate the negatives and prints, treating them as originals rather than a pristine image. Seizing the opportunity to push the medium into new realms, Mark created the “sandwich print” process. He made a color print, photographed it in black and white, and then paired the negatives together to create a single image.

The result was hazy and ethereal, disembodied from the flesh and occupying the place of memory and spirit. The photographs feel far away, from another time and place, like artifacts that we may return to with a sense of wonder and awe. Their physicality is visceral, almost as though Mark had only just dashed off the handwritten notes around the frame of the photograph detailing who, what, when.

But the Polaroids were just one on Mark’s media of choice, as he also worked in photogravure, cyanotypes, lithography, and transferred Super 8 film, exploring ways to deconstruct and reconstruct the image. He highlighted the technical imperfections of the work, while leaving the scratches, dust, and fingerprints from the developing process intact, giving the prints a physicality that ran counter to the intangible sensation of the images.

Mark’s forays beneath the surface of the picture reflected the way he lived life. “He wasn’t afraid of anything and intimacy didn’t scare him,” says Brian. “He had that sort of brutal honesty with himself and that helped his friends to let down their guard and participate. That intimacy with people like Jack Pierson, Tabboo!, and Gail Thacker allowed them to push and challenge each other, and create another level of trust.”

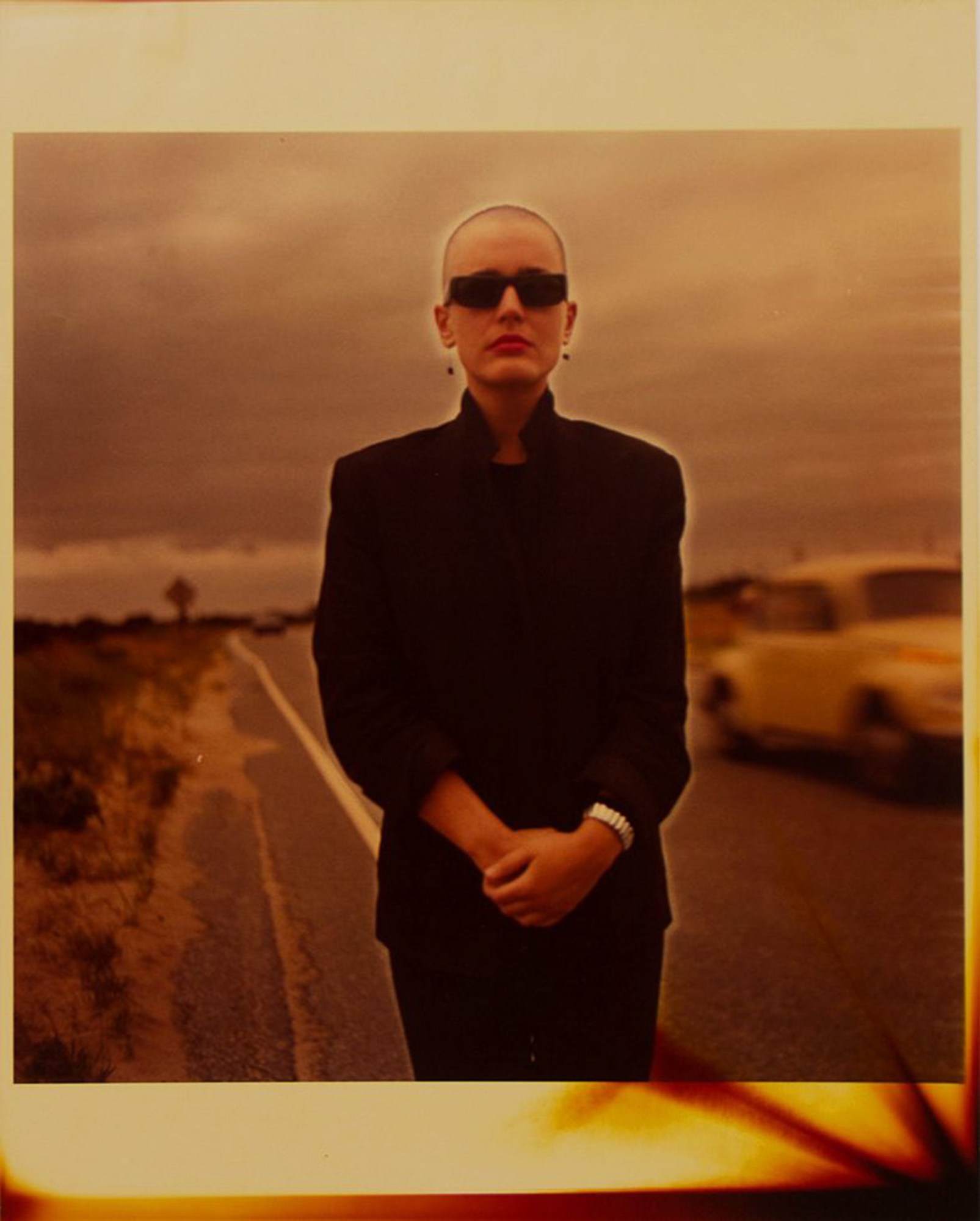

In 1985, Mark moved to Jersey City and began frequenting the downtown New York scene centered in the East Village. During the final decade of his life, Mark was intensely prolific, using the little time he had left to create a body of work playing with gender, sexuality, identity, and community that would go on to inspire generation of queer image makers.

The following year, Mark was diagnosed with HIV – the same year he had his first solo exhibition at Pat Hearn’s fabled East Village gallery. After his death in 1989, Pat continued forth, presenting a series of memorial exhibitions during the ‘90s until her own untimely death in 2000. More recently, Brian has been integral to the preservation of Mark’s singular legacy.

“Mark was making all these statements about sexuality at a time when not a lot of other people were doing so, and it was very brave and unusual,” says Brian. “He was very loud about it and never censored himself. He had come out early and was comfortable with his own sexuality, which put him at an advantage. The AIDS crisis entered his work and he wasn’t afraid of showing himself in a compromised light. Up until his last day, he was taking pictures of his emaciated body in an in-your-face sort of manner.”

Mark’s final years were marked by a sense of urgency, knowing the end was near. Although his life was cut short, his work lives on, prefiguring the times in which we live today. “There‘s always a nostalgia for the past but I think it’s deeper than that,” says Brian. “There is a need for change and people are willing to raise their voices, stand up and fight.”

Works by Mark Morrisroe are on view March 31–April 2, 2023, at the Clamp booth during The Photography Show in New York.

Credits

All images courtesy of CLAMP, New York. © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur.