The revolution began, as all good revolutions should, with four British lads from the suburbs boarding a flight to Ibiza. DJs Paul Oakenfold, Johnny Walker, Danny Rampling and Nicky Holloway, headed to the Balearic island in 1987 in search of something more than sun, sand and frosty jugs of ice cold cerveza.

Out there in San Antonio, before the town became the alcopop-soaked destination it is today, they bumped into another DJ, Trevor Fung. Fung had been playing on the island for several years at that point, ping-ponging between there and Streatham, of all places.

An Ibizan fixture, he introduced his fellow countrymen to two things that, when combined, would change the face of British youth culture: the open-air superclub Amnesia, and the drug ecstasy.

The combination of balmy Balearic air, very strong narcotics and the freewheeling music policy adopted by the club’s most notable resident, Argentinian selector Alfredo, was a revelation. The foursome tottered onto flights back to Britain, brains bulging with ideas, and within a few months the UK’s club scene had been revamped, re-energised and revitalised.

What happened after — the birth of the rave movement, the introduction of ecstasy to the general population, the tie-dye T-shirts and the eventual scene-dismantling implications of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 — was nothing short of miraculous. It was 1988. It was the Second Summer of Love. It was Great Britain loosening its tie, and its reverberations are being felt to this very day.

88 is the moment when a nation took cultural ownership of a scene that’d been birthed by our transatlantic cousins. We took the technoid fantasies of post-industrial Detroit and plonked them in an airhanger just off the M4, wrapped them in baggy Stussy t-shirts and made a solemn vow to never forget exactly just how that first pinger felt.

In a way it is a perfect distillation of how subcultural scenes can have incredible, potent and near-permanent ramifications outside of their inner-inhabitants, reshaping lives in perpetuity. It is a moment in history where history itself was being rewritten every night of the week, in bedsits in Hulme and in fields far from the madding crowd.

It is also a moment in time that we’ve found ourselves stuck in. But maybe now, 30 years on, we need to think about leaving it behind.

“It is tempting to see the present as a place where possibility has been made null and void. Except culture doesn’t have to by cyclical.”

“The culture of acid house and rave permeated everything in the northwest back then,” says director, Rig Out boss and rave aficionado Glenn Kitson. “My older cousin went to all the Blackburn acid parties in 88 and 89. All the older lot were going raving and doing E’s and all the younger lot where hanging around the park listening to house and acid and taking trips and smoking draw.”

Kitson’s experiences — he went to his first “semi-rave” at Manchester’s GMEX in 1990 at the age of 14 — aren’t a localised incident. And it wasn’t just localised to music either. “It had a palpable energy that filtered into art, design, architecture, writing and culture,” Kitson says of the years that immediately followed 88’s acid explosion.

Three decades down the line, that energy is spent. You can get a sense of it, of course, by delving back into the past. You can flick through Gavin Watson’s Raving ‘89. You can spend an evening clicking through grainy video after grainy video of long-forgotten nights at Quadrant Park in Bootle. You can even, if you so wish, head to festivals like M25 where club culture is preserved in aspic and nothing of worth has happened since John Major walked into 10 Downing Street. The rave nostalgia complex is running riot.

What, you might ask, is so wrong about that? Why shouldn’t clubbers young and old — the ravers themselves and the children conceived on long, languorous summer afternoons after the parties and the after-parties had ended — look back on a past that seems so perfect, so at odds with the here and now? What’s the problem with indulging in a dose of dancing into history?

The problem with looking back too often is that it makes the present seem fatiguing and the future a near impossibility. This is a problem that club culture struggles with, and seemingly has done ever since some bright spark — and there’s a painfully compelling case to be made that said spark was Jimmy Saville — realised that playing one record after another was a good way to make money.

And it is a problem that clubbing needs to address if it’s to ever have a Third Summer of Love.

“That way of life is still possible. But things change, clubs change and we need to change with them.”

“Dance music for has always been about freeing your mind, surrounding yourself with open, free-minded, friendly people,” Rupert Cogan tells us. Cogan, better known as DJ Haus, is a prolific producer and DJ who runs the Unknown to the Unknown and Hot Haus labels, imprints that thrive off the DIY ethos and ecstatic energy of early rave parties and records, rejigged for the 21st century. That, he thinks, is still the case now. “Whether you’re dancing to digi dub, trance or jungle it makes no difference — if you are there for the right reason.”

Cogan has a point. The ‘reason’ hasn’t changed; not since disco, not since acid house, not since dubstep or moombahton or aquacrunk, or skweee. But if the reason has remained constant — escaping reality for a night — why are we bombarded with recycling and rehashing?

This is, of course, the post-postmodern condition. We no longer know or care what our sources are, and if we do know, we certainly don’t care about ripping them off.

You hear it in the endless rave revivalism clogging up record shop shelves and the digital cascades of streaming services. It is as if the last 30 years counted for nothing, and the dreams of dank warehouses strangled the life out of the thrill of the future.

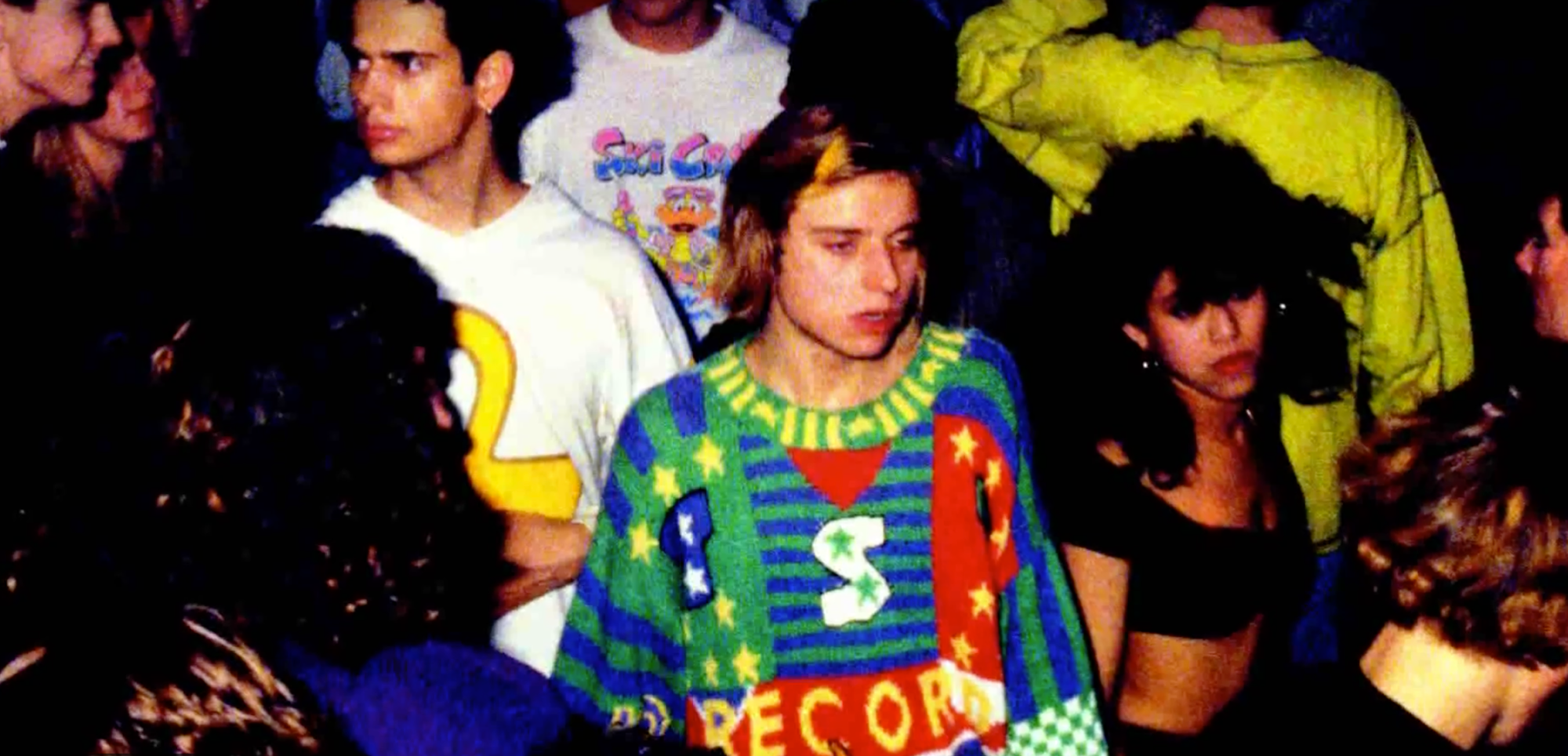

You see that too, in the way Depop or Too Hot are stuffed to the gills with clothes pulled from the wardrobes of original ravers, sold on to the Warehouse Project contingent for another Saturday stroll down memory lane by people who weren’t alive when Altern 8 were on Top of the Pops. It is rave attire as both fancy dress, homage, and a desperate link to the past — that allegedly perfect time, when skies were blue, the grass was green, and a gary cost six pence and lasted a fortnight.

“I was on Kensington High St this afternoon,” Kitson says, “and I saw a girl wearing an oversized beige corduroy jacket, white jeans and Kicker boots. She could have dressed like that 28 years ago and would have fit right in. I liked it.”

Whether or not that speaks of a kind of generational conservatism, I’ll let you decide.

When Kitson — whose Instagram page is a goldmine for anyone looking to rejig rarer looks from the rave days — tells me that back in the day “it felt like anything was possible, even if it was just for the weekend”. I know what he’s getting at: when a night out has become little more than an opportunity to post a few Instagram stories and a boast or two on Twitter the day after, it is tempting to see the present as a place where possibility has been made null and void. Except this isn’t actually the case. Culture doesn’t have to by cyclical.

“There are nights and parties that want to sever that link to the much-discussed past. They could change your life if you just let them.”

For the last few years, and it is understandably and justly linked closely and accurately to the spate of club and venue closures across the UK, the commonly peddled myth is that nightlife is dead, or dying, or at least sort of convulsing quietly in the corner of a party somewhere.

The rise of the festival, the increasingly prevalent distrust of late licenses from the perspective of local councils and post-austerity lack of disposable income for the bulk of the punters who make up clubland’s population — all these things, we were told, were going to kill the nightclub. This hasn’t happened yet. Why? Because that desire — ”you’ll always find people wanting to free their minds,” as Cogan puts it — has not been lost.

It is important to remember that 88 didn’t emerge out of nowhere — it was, like punk, like the hippy movement, like dadaism or surrealism or the majority of cultural movements in the history of humankind — an oppositional thing. A reaction. It stemmed from the drudgery of the tailend of Thatcher’s Britain and a desperate unconscious need to disconnect from reality, weekend after weekend. It offered a way of life, outside of conventionality.

That way of life is still possible. Not, perhaps, in the way it was when the world was shaped like a mitsubishi and everyone held hands as Voodoo Ray became the national anthem. But things change, clubs change, and we need to change with them. The acceptance and openness of rave culture at its very best still exists; its just been forced to hide underground where it came from. At vogue balls and club music parties, in record shops and on catwalks, you’ll find, if you’re willing to look and listen hard enough. It nods to 88, but doesn’t swallow it whole. “Concentrate on the here and now,” Kitson says. “Referencing the past doesn’t mean it has to be retro.”

This summer, do yourself a favour. Do not perpetuate the myth that nothing has been good since Terry Farley was in short trousers and the Berlin Wall was still erect. Do not believe everything you hear about what happens when 200,000 people danced for days on end in fields. Look around you and take stock of what is happening here in the now.

Clubbing has been through its boom and bust phase, and is rebuilding itself up from the ground. Visit venues like the White Hotel in Manchester and go to parties like Come Thru in Leeds, listen intently to what producers like Finn and DJs like Amy Becker are doing — step back and watch culture unfurling in front of your very eyes. Night after night, weekend after weekend, there are nights and parties that want to sever that link to the much-discussed past. They could change your life if you just let them.

So dive in, headfirst, seeing what works and what doesn’t, discovering the things that you’ll be looking back on in 30 years time like they were the best thing in the world. Because they might just be.