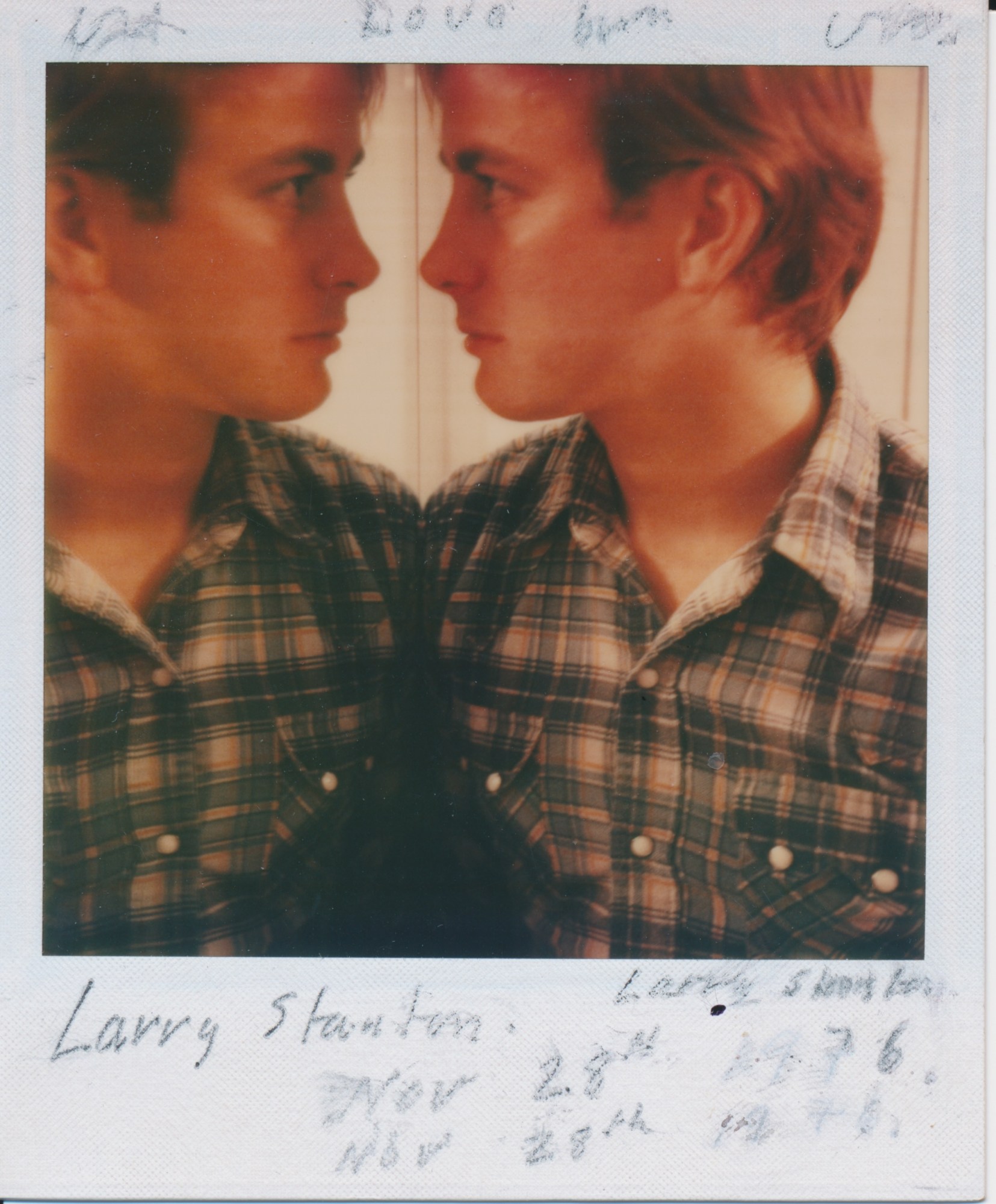

In the years before the Stonewall Uprising, New York’s LGBTQ scene was ensconced underground, flourishing in secret sanctuaries like the Fire Island Pines. It was here, back in the summer of 1967, that Arthur Lambert first crossed paths with Larry Stanton, a new kid on the block who was the talk of the town.

Arthur spotted the dashing young blonde strolling across the boardwalk with singular aplomb while lunching with some friends at a restaurant on the harbour. In an instant, Arthur was on his feet and out the door, introducing himself with a breathless mix of nerves and desire. Fearlessly shooting his shot, Arthur invited Larry to stay in his apartment — and from those modest arrangements, a lifelong bond was forged.

Now in his late 80s, Arthur looks back at their relationship with tenderness and care, still brought to tears as he remembers a generation of gay men — including Larry — who perished in the early years of the AIDS epidemic. On 19 January, Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York presents a new exhibition, Larry Stanton Drawings and Paintings 1974–84, which celebrates a cadre of bright young things just getting their start in the world only to die before they had the chance to truly live.

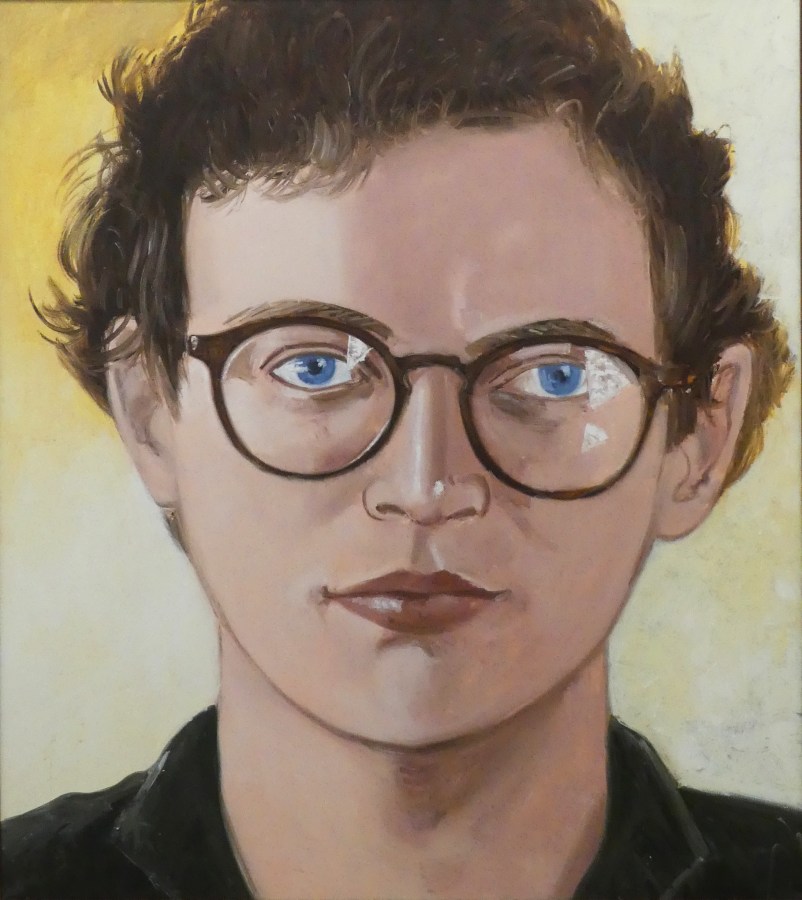

“This is not just the story of Larry; it’s the story of that period when so many people died,” Arthur says. “It was so tragic. Many years ago, I was looking through a book in the library, pictures of Jews in 1939, and I felt the same way about [Larry’s portraits of] the kids — they had no time to make their mark or develop real character in their faces. Larry caught their youth and enthusiasm. It’s amazing to me that he got so many kids to come sit for him. His portraits were the only record that they passed through this way.”

As the first generation to come of age after the war, Larry grew up amid the narrow cis-heteronormative roles that dominated mid-20th-century life, never quite fitting into the archetypical image of American youth farmed out to the world. “They left their hometowns because they were small, and they didn’t have much affection for gay people,” Arthur says. “They felt frozen, and so they came to New York.” After graduating high school, Larry did just this, arriving in Manhattan to study at The Cooper Union on scholarship, only to drop out after a single semester. He took a job at Serendipity, the fabled ice cream parlour on East 60th Street at the heart of the city’s gay scene.

The year after they met, Arthur and Larry moved to Los Angeles, where they maintained an open relationship. “I bought him a little Volkswagen,” Arthur remembers. “Every night, he went down to a non-alcohol bar called Gino’s, which was mostly for people his age and often brought someone home, which didn’t bother me. Actually, it was very nice. I got to meet a lot of people I wouldn’t have otherwise met.”

Then 34, Arthur felt a sense of responsibility to help guide 20-year-old Larry during this formative time in his life. After learning the young man dreamed of becoming an artist, Arthur enrolled Larry in the Art Center College of Design, then the best art school in Southern California. They began connecting with luminaries like David Hockney, Christopher Isherwood, Don Bachardy, and Henry Geldzahler, Curator of Contemporary Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who was one of the most influential figures of the time.

Henry, who first met Larry one night at Gino’s, described his beauty as akin to looking at the sun. The intrigue was mutual. “Henry was quite a character,” Arthur says. “He spent almost every day at artists’ studios and knew more about the art world in New York than anyone else. Larry was fascinated by Henry because he had access to the art world that Larry wanted to invade.”

In 1969, Larry returned to New York alone, took over his father’s rent-controlled apartment in Greenwich Village and began visiting the Met every day. Through his connections with Henry, Larry became deeply immersed in the scene, making a strong impression on all he encountered and fostering new bonds with artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Barnett Newman. “When I got back to New York in 1972, Larry had made a lot of friends — older men that wanted to take him various places. He went through Africa on safari, to Paris and Rome,” Arthur says.

Larry had his first exhibition at Gotham Gallery and secured a basement studio in Soho where he could paint. But everything turned upside down when his beloved mother was diagnosed with cancer in 1975. “He loved her so much, but he couldn’t go see her in the hospital very often,” Arthur says. “When she died in 1978, he felt incredibly guilty. She was the only one in the family who had faith in him, and he wanted to prove that he was worth something.”

Larry suffered a mental breakdown and was hospitalised for a year at St. Vincent’s Hospital. “When he went in, I was told that the doctors said he was hopeless and he couldn’t be cured, but he had a marvellous therapist named Dr. Mayo,” Arthur says. “She was a Black woman who was the head of the psychiatry department at St. Vincent’s, and she took a loving for Larry. Her son, who was 14 at the time, fell off the roof of her building and died. She saw Larry as a kind of replacement son.”

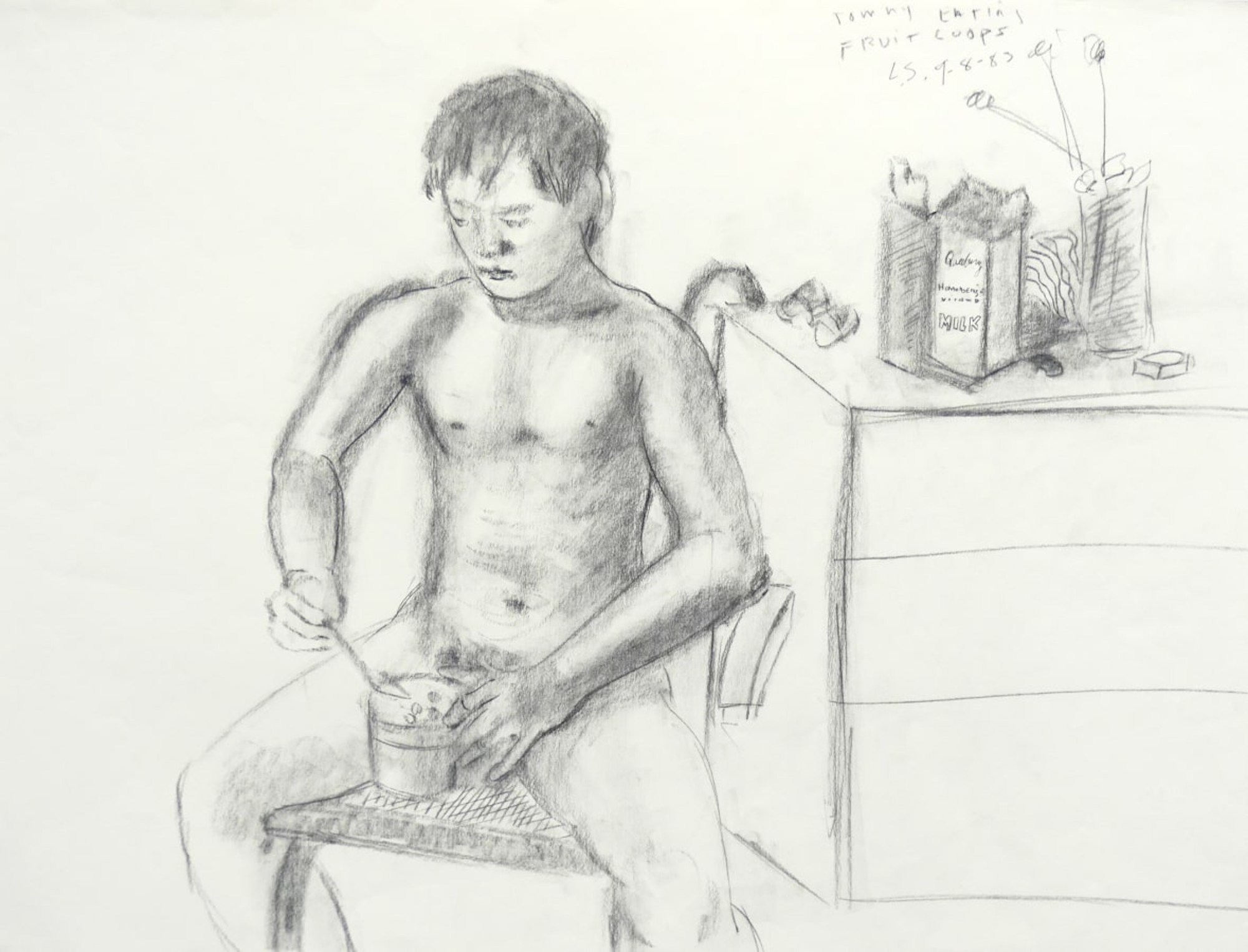

Under Dr. Mayo’s care, Larry’s condition improved. After he was released, he devoted himself to the task at hand: building his practice as a portrait painter. He moved into a new studio, which became a popular destination for young writers, poets, and artists coming of age and seeking community. Fuelled by passion and purpose, Larry made portraits in charcoal, oil crayon, pencil, pen, and paint of drawing friends, familial relations, and people he met while wandering the streets of New York.

David Hockney, Larry’s lifelong friend and contemporary, astutely observed in the 1986 book Larry Stanton Painting and Drawing, “The portraitist is an observer of people, his attitudes and feelings will be reflected in his observations and, usually, the interest in personality makes one study faces, other aspects of personality show in the body; posture, ways of moving, etc., but most is revealed in the face. People make their own faces, and Larry knew this instinctively.”

In the recently published book, Larry Stanton: Think of Me When It Thunders, Arthur explains Larry’s portrait process. “He would find [models] mostly in gay bars, take them back to his apartment and draw them.” Although he did not know it at the time, Larry was creating a memorial to those who would share his same fate just as he was finally receiving recognition as an artist. In April 1984, his work was featured in a major group exhibition at PS 1 in Queens, but shortly thereafter, he was hospitalised for PCP pneumonia and then recognised as among AIDS patients at a time when there were no tests or treatments for HIV.

Larry spent the first 10 days in the hospital drawing with fervour. As his condition worsened, his work became the primary way to express his terror, rage, pain, and hope. “The nurses asked me, ‘Doesn’t he realise he is dying?’” Arthur remembers. “But it was so important to him. He just couldn’t stop. Even though he was dying, there was nothing wrong with him mentally.”

Four weeks after he was admitted to the hospital, Larry was dead, and Arthur inherited the estate. “He left me everything — 300 paintings and 450 drawings, and I couldn’t sell anything,” Arthur says, “Larry only sold about seven paintings in his life. People weren’t interested in portraits of boys, but it’s completely changed now. It’s taken over 30 years for people to recognise his work. It’s an achievement.”

‘Larry Stanton Drawings and Paintings 1974–84‘ is on view 9 January – 4 March 2023 at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York. ‘Larry Stanton: Think of Me When It Thunders‘ is published by Apartamento. Acne Studios recently released a capsule collection and travelling exhibition of the work of Larry Stanton.

Credits

All images courtesy of The Estate of Larry Stanton and Daniel Cooney Fine Art, NYC