Even before Mu Tunç could talk he was making the sign of the horns. We’re chatting over Skype and looking through a selection of photographs he’d sent over earlier in the week, a huge zip file titled “My Brother & The Evolution of Punk/Hardcore Scene in Istanbul”. The 31-year-old filmmaker is currently in Los Angeles, working on his second movie, and although he may be 5,000 miles away, you can still sense the emotion in his voice as he settles on an image of two young boys reclined on a family sofa, arms around their mother. On the shirt of one of the boys is the logo of German speed metal band Grinder.

“This is our home and it’s a crazy picture,” he says. “You see me doing the devil horns and I’m not even four years old. This isn’t like seeing someone listening to a punk record in Berlin or New York. This is a really conservative culture. For this to exist…” He trails off. “It’s beyond weird.”

Mu grew up in a peaceful home in the middle class district of Merter, just north of Istanbul’s E5 highway. His father, Altan, worked for the Government Office of Public Works and Settlement, a steady job he’d taken when Mu’s mother, Olcay, fell pregnant with his brother, Orkun, in the winter of 1976. Altan had been a singer before then, winning a nationwide competition and signing to one of Turkey’s leading record companies, Melek Plak (Angel Records) in the mid-1970s. A period marked by escalating right-wing and left-wing tensions, he saw his burgeoning career come to an end following the bloody coup d’etat of 1980 — a violent eruption in which 50 people were executed, 500,000 arrested and hundreds more died in prison.

“The army was taking control and they wanted everybody to join,” Mu says, of his father’s forced military service. “When he returned 18 months later, his career was lost. No one in the music business remembered him. The entertainment industries had been changed by the army and his music was deemed too artistic for the market.” Instead, the performance bug had passed onto his son.

Orkun was born in the summer of 1977, about a month after British band the Sex Pistols attempted to interrupt the Queen’s Silver Jubilee celebrations by performing God Save the Queen from a boat on the River Thames. Nine years older than Mu, he’d grow up to be his brother’s idol. Mu followed his every move, what he was listening to, what he was wearing. “My brother and his friends were having their cool moment,” he describes of their early teenage rebellions. “Listening to bands and drinking coke and wearing white sneakers.”

Following the coup, the only way to keep up with music from the west was through records smuggled in via pilots entering the country. They’d be sold off to local bootleggers, who’d make illegal cassettes of two or three albums at a time. A popular store, Eloy, was owned by Eloy Hakan, a former street seller who’d amassed a collection of 4000 rock and metal cassettes following the coup and sold them from a cave-like, poster-covered shop in the densely populated neighbourhood of Bakırköy. It was here that a teenage Orkun first discovered hardcore via a bootleg cassette of American bands D.R.I and M.O.D.

An extension of the LA punk scene, even by today’s standards, D.R.I.’s 1989 crossover hit Beneath the Wheel sounds like a bludgeoning shot of adrenaline to the chest. To a 12-year-old kid growing up under the iron fist of Kenan Evren, the general who led the military coup nine years earlier, it must have been practically transcendental. “Orkun found music,” explains Mu. “He and a small group of his friends were exploring extreme and heavy music totally foreign to their surroundings. This was super rare.”

On a diet of cassettes fed to him by Eloy’s, Orkun began to expand his musical palette to crossover bands such as Suicidal Tendencies, S.O.D., Nuclear Assault, Slayer, Reactor and Tankard. Without his father’s knowledge, he went to a music store and made an agreement to buy a drum kit in monthly instalments. When Altan found out, Mu says he went crazy; he didn’t want him to be a musician. But by then it was too late — Orkun and his schoolmates were already ensconced in the family garage every night, throwing private concerts for their friends.

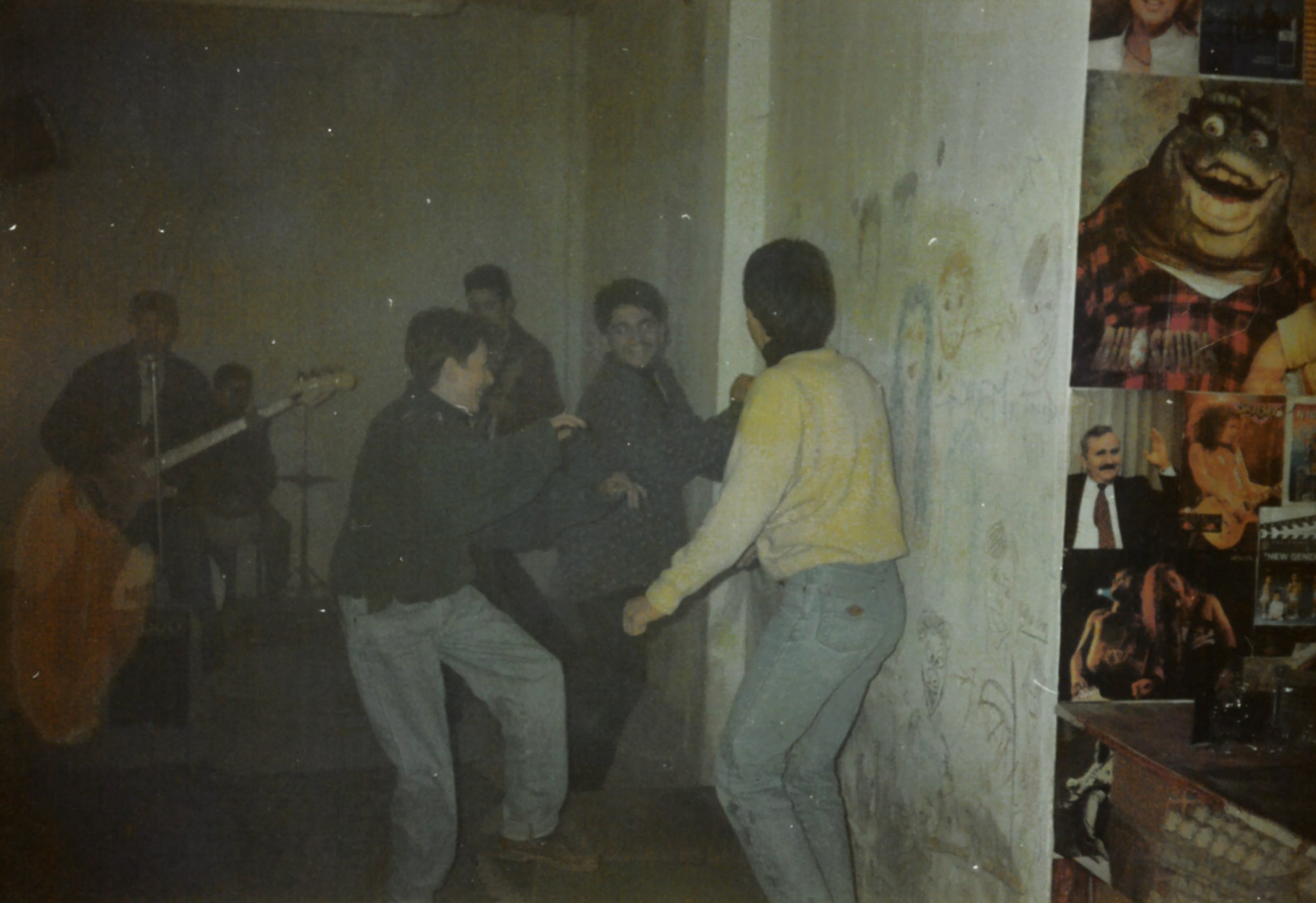

While in the UK and United States, punk was synonymous with teenage rebellion, for those in 1970s Turkey, even on the far left, it had remained as much a symbol of western decadence as the institutions it supposedly rebelled against. Now, ten years later than its neighbours in the west, inside a small, ink-daubed garage in middle class Merter, something was beginning to change. “I believe this is one of the first times historically we are seeing people making punk and hardcore music in a Muslim culture,” Mu says, of the pictures showing blue jeaned kids with borrowed amplifiers. “These kids didn’t understand what kind of music they were making, they just liked to hang out.” Turkey was having its punk moment at last.

Tired of the apolitical apathy of the 1980s, a spate of bands began to emerge in the city’s suburbs. Performing makeshift shows in garages just like Orkun’s, this new wave of teenagers wrote about anti-nationalism, racism, social injustice, consumerism and animal rights. They were outward looking at a time when the country, too, was beginning to open up, at least economically, under new president Turgut Özal; circulating music through homemade demo cassettes and communicating with one another via the xeroxed pages of fanzines.

Although the first group to actively play punk in Turkey is widely considered to be Headbangers in 1987, it wasn’t until July 1992 that enough of a scene had developed for a first hardcore festival — Punk HC Fest — to be held in the capital of Ankara. “They were so proud in this picture,” Mu describes of an image that depicts Orkun’s first band, Violent Pop, in front of a series of posters, notable for the inclusion of Turkey’s first all-female punk band, Spinners (see also the excellent Tampon). “The open mindedness kills me because I’m not even sure this kind of a thing can exist anymore,” he sighs. “Conservatism is so high, that people believe nothing can be achieved in the east anymore. But some really cool things happened here. This is the proof.”

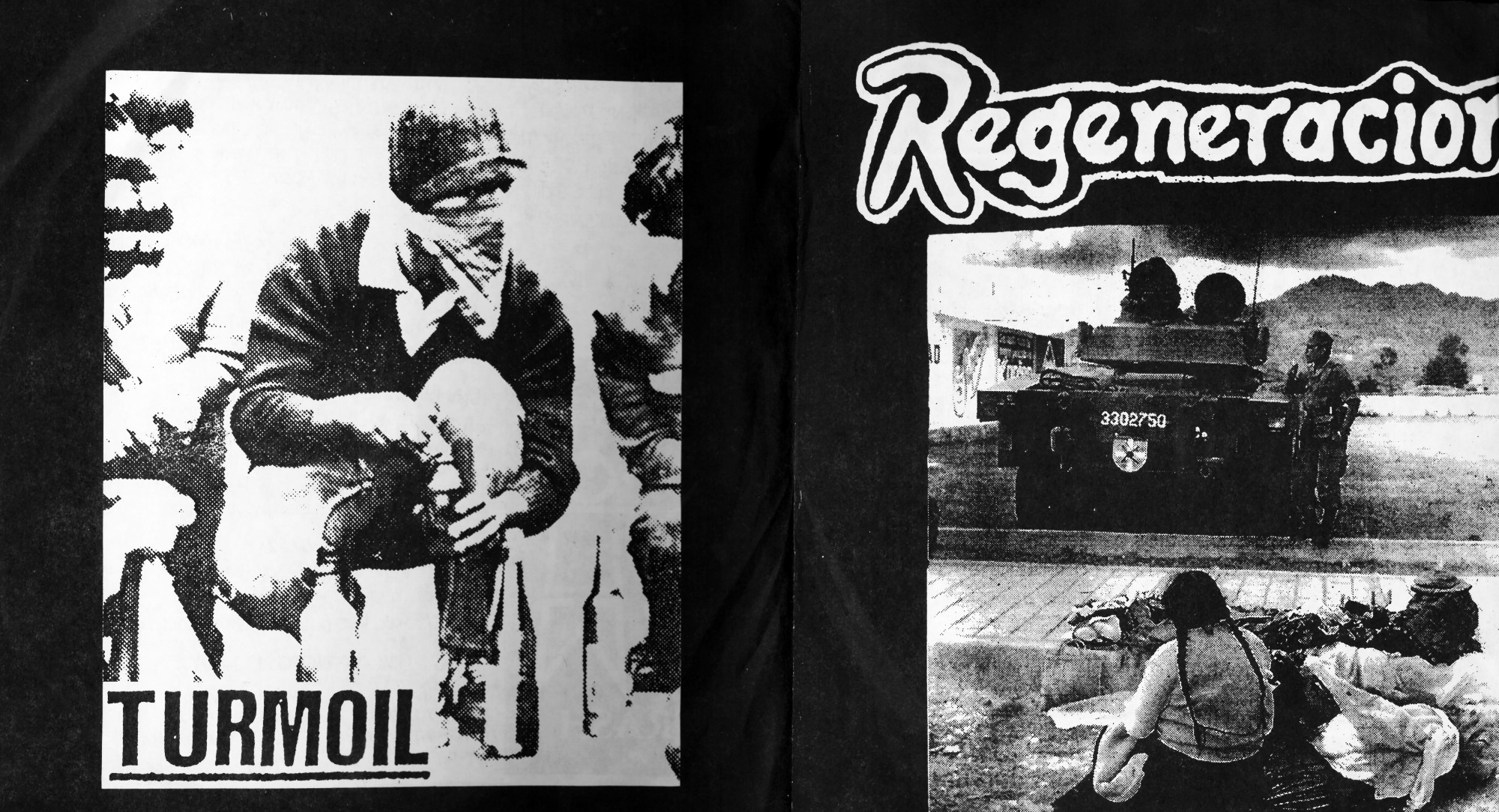

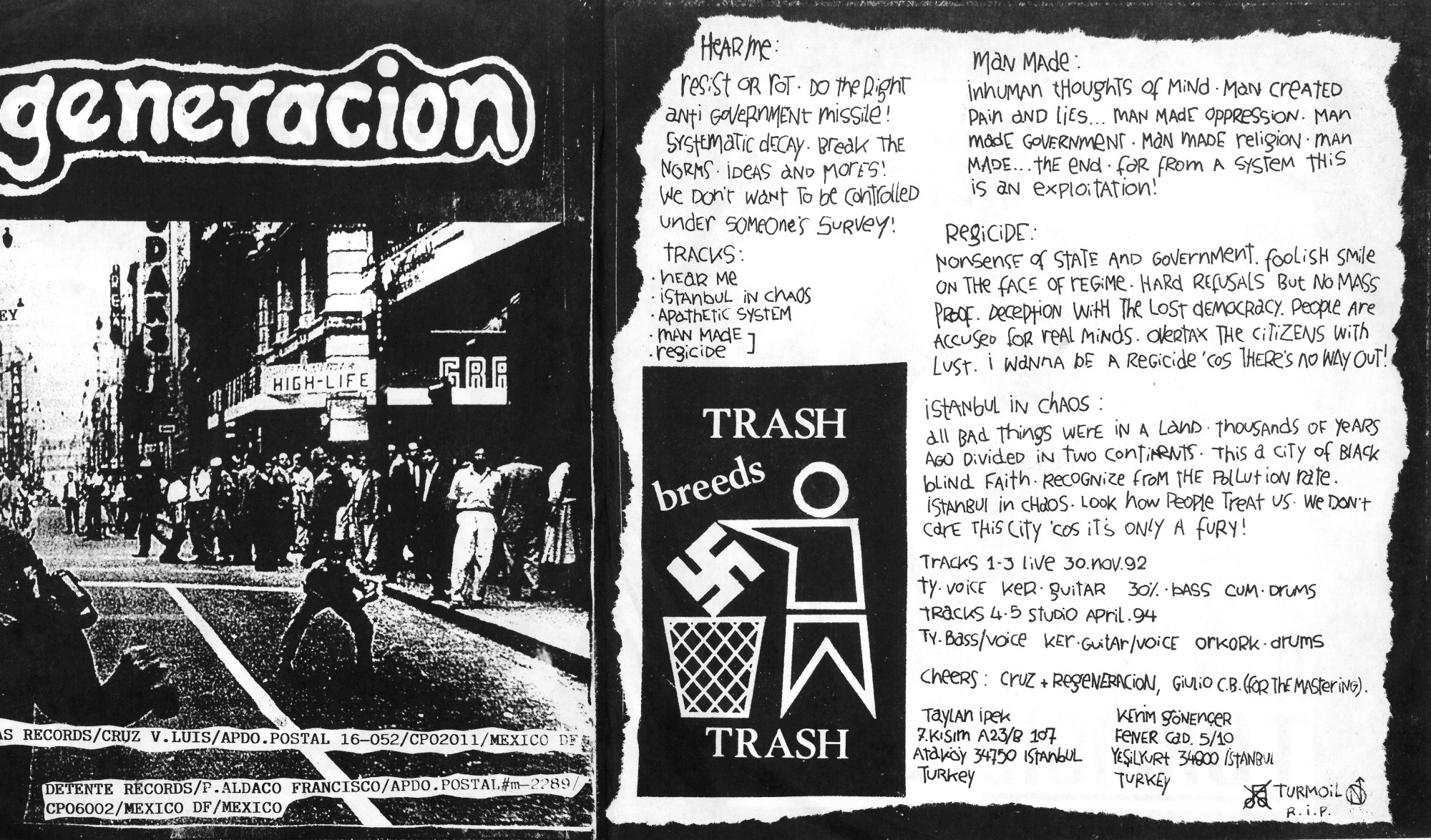

Further evidence comes in the genuinely thrilling music created by these bands. In 1994, Orkun’s second group, the brilliantly chaotic Turmoil, made history by becoming — along with Radical Noise, Necrosis — one of the first Turkish hardcore groups to have their records released abroad: a split 7″ with Belgian grindcore act ACOUSTIC GRINDER. “They basically recorded and sent a tape through mail,” Mu explains. “There wasn’t internet, but somehow they communicated and these people produced the record.” Further splits with Inkisição from Portugal, Depress from Malaysia and Regeneracion from Mexico followed, while a mooted release with Doom fell through when Turmoil failed to recognise the act’s fledgling potential (they went on to become one of hardcore’s most pivotal bands).

“Turmoil started playing more concerts, forming new bands that collaborated with each other,” Mu says. “It became a scene when, literally, there is no scene in Istanbul now. That’s the problem. Their lyrics addressing eco-terrorism, homophobia, cosmetic products and Islamic extremism are still relevant today.”

By the end of the century, Turkey’s hardcore scene had all but died out. A period of moral panic that peaked with the murder of a teenage girl by purported Satanist metal fans in 1999 created a national disdain for alternative music. Orkun, who had long suffered from stress at his father’s disapproval of his chosen career, suffered a heart attack at the age of 23 that lead him to stay in an intensive care unit for over two months. Punk was over — destined to be but a short, sharp, electrifying shock to the country’s youth culture.

Today, Mu’s preparing to release a feature film, ARADA, based on his experiences. The story of a punk kid who attempts to track down a cruise ticket to California on the night of his birthday, the making of it was emotional — not least for how close to home it felt. “This kid feels trapped in Istanbul,” Mu says. “He thinks that if he stays he’ll become a failed musician like his father. He thinks the only way he can achieve his dreams is by leaving Istanbul.

“That’s why this story is really important,” he continues. “It’s not about the movie anymore. It’s about this whole thing. It’s about inspiration for people, to show that we are actually living in a really cool city. My brother’s insane story of forming these punk and hardcore bands in a 90s Istanbul where all the resources are ultra-limited is living proof that anything’s possible. Hopefully someone will read this article and it will show them that underground energy still matters.” Who knows, that person might even have an empty garage.

ARADA, Turkey’s “first punk movie”, is released later this year.