Throughout the span of her prolific, decades-long career, photographer Mary Ellen Mark made it her mission to document people on the margins of society — those whom she referred to as the “unfamous.” From homeless teens on the streets of Seattle to circus performers in India, she displayed unwavering compassion for every subject she met and inevitably kept in touch with most of them, a practice she maintained until her death in 2015.

Back in 1976, Mary Ellen undertook her biggest long-term project yet — photographing the women of Ward 81, an all-female psychiatric treatment facility inside Oregon State Hospital in Salem. She had her first encounter with the residents — many of whom were deemed ‘dangerous,’ — while on the set of the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1975. After a back-and-forth with the institution, along with the patients and their families, she managed to gain access almost a year later. Together with her collaborator, licensed therapist Dr. Karen Folger Jacobs, she lived and worked in Ward 81 for almost five weeks, returning to an adjacent wing at night to sleep.

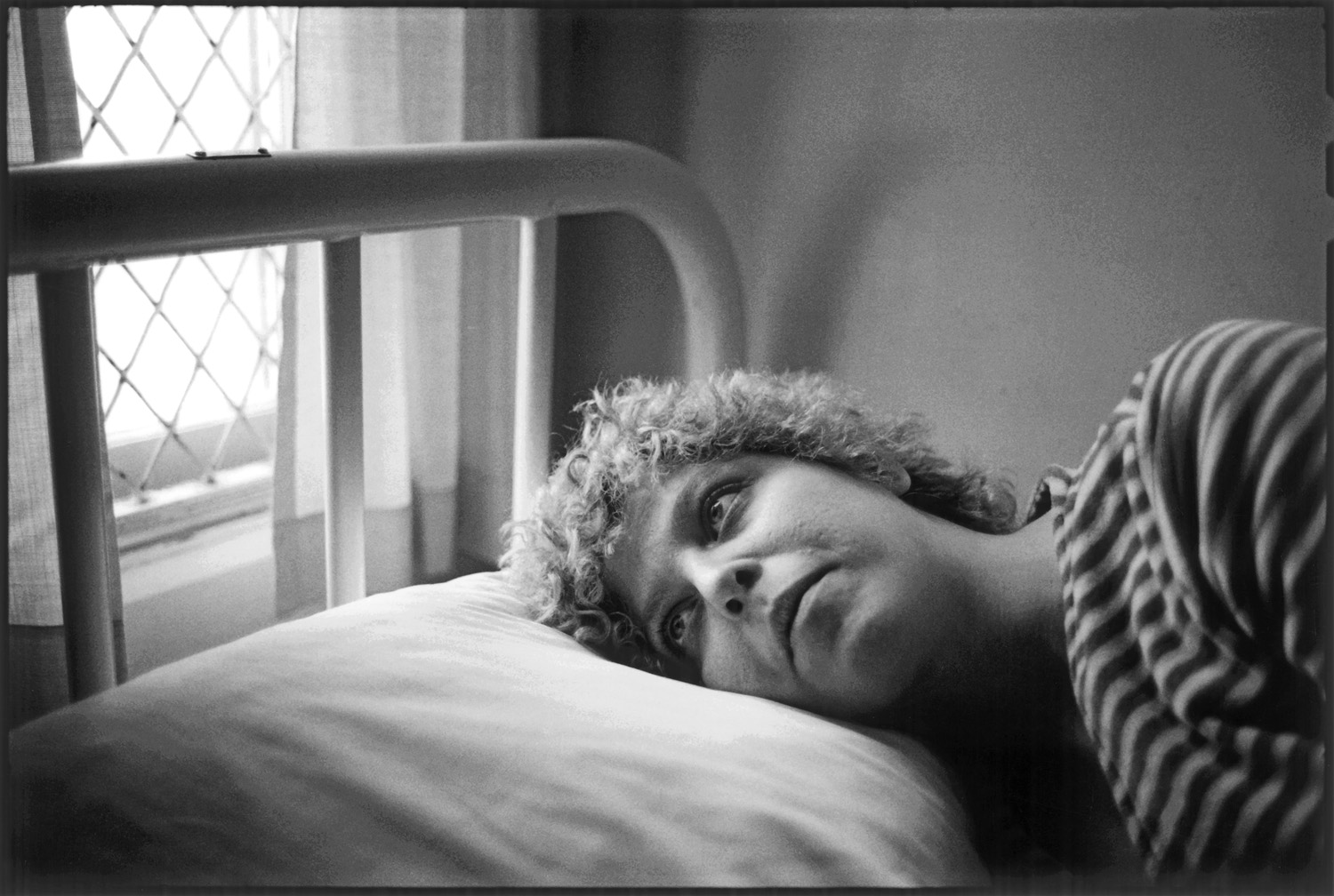

“I became interested in the patients and asked their permission to come back later for some pictures,” Mary Ellen recalled later in an interview. “I lived very intensively with the patients for [several] weeks. I slept in a small cell and I ate with them in the morning. Just like everywhere, during my presence, people behaved tough and outside themselves [at first]. At some point, they got used to me and forgot I was there at all.”

Two years later, Mary Ellen published her seminal book Ward 81, which was praised for its nuanced portrayal of female psychiatric patients in the United States. A new exhibition now on view at the Image Centre in Toronto, Mary Ellen Mark: Ward 81, revisits this captivating body of work through a collection of 130 photographs, alongside audio recordings and other archival materials which have never been seen before. Created in collaboration with the Mary Ellen Mark Foundation and her husband Martin Bell, the exhibition accompanies a recent photo book from Steidl, Ward 81: Voices, which was released in January. Along with the show, the monograph expands upon Mary Ellen’s original book, providing a behind-the-scenes look at the project and some of her subjects’ distinct identities.

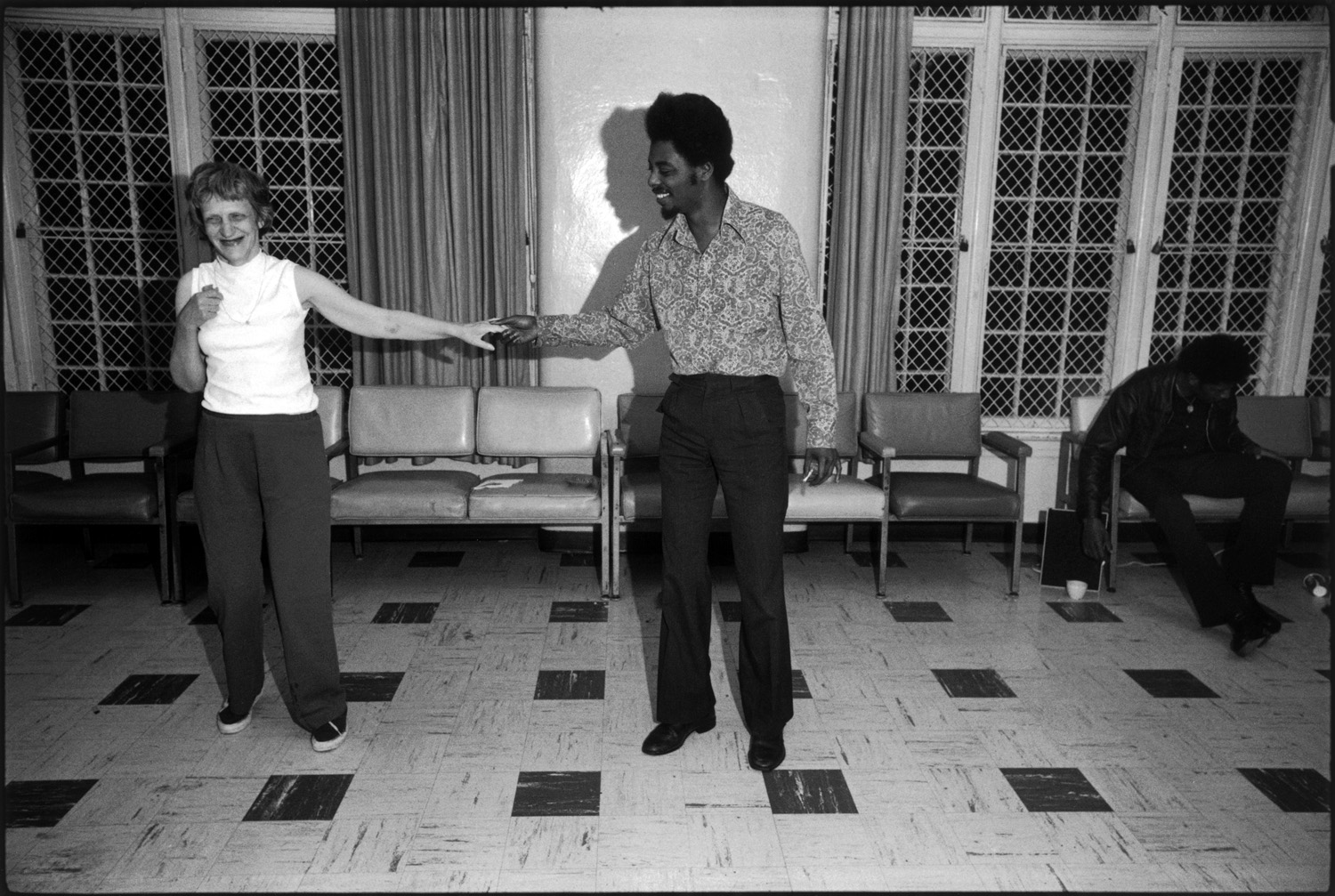

“We have quotes from the women on display, as well as some audio recordings and lots of other materials that contextualize Mary Ellen’s work and the time she spent in the ward,” says Gaëlle Morel, one of the show’s curators. “As a photographer, she really wanted to understand the quotidian lives of these women and what was happening to them. And in the process, of course, she also questioned the validity of the institution in a compelling way.”

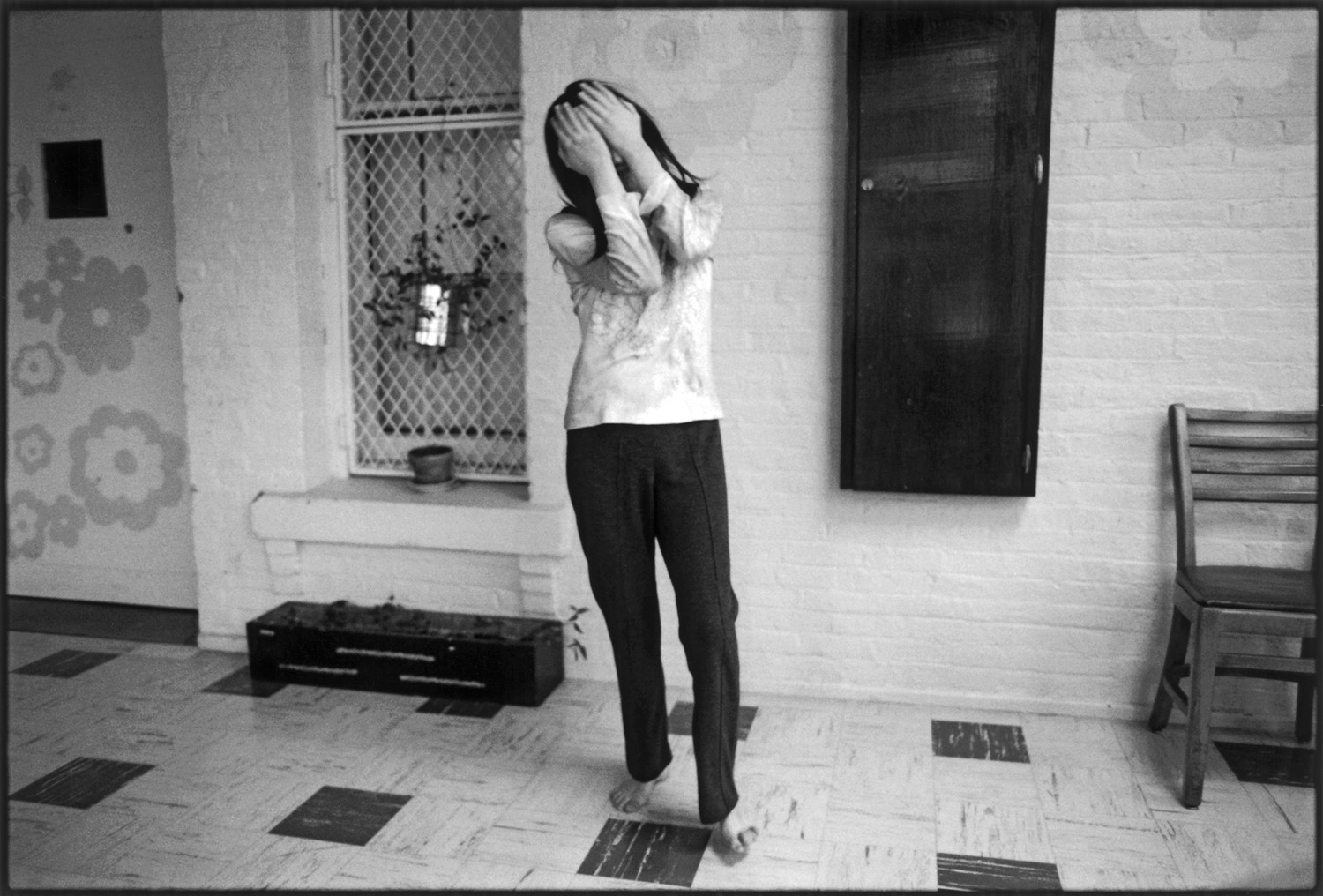

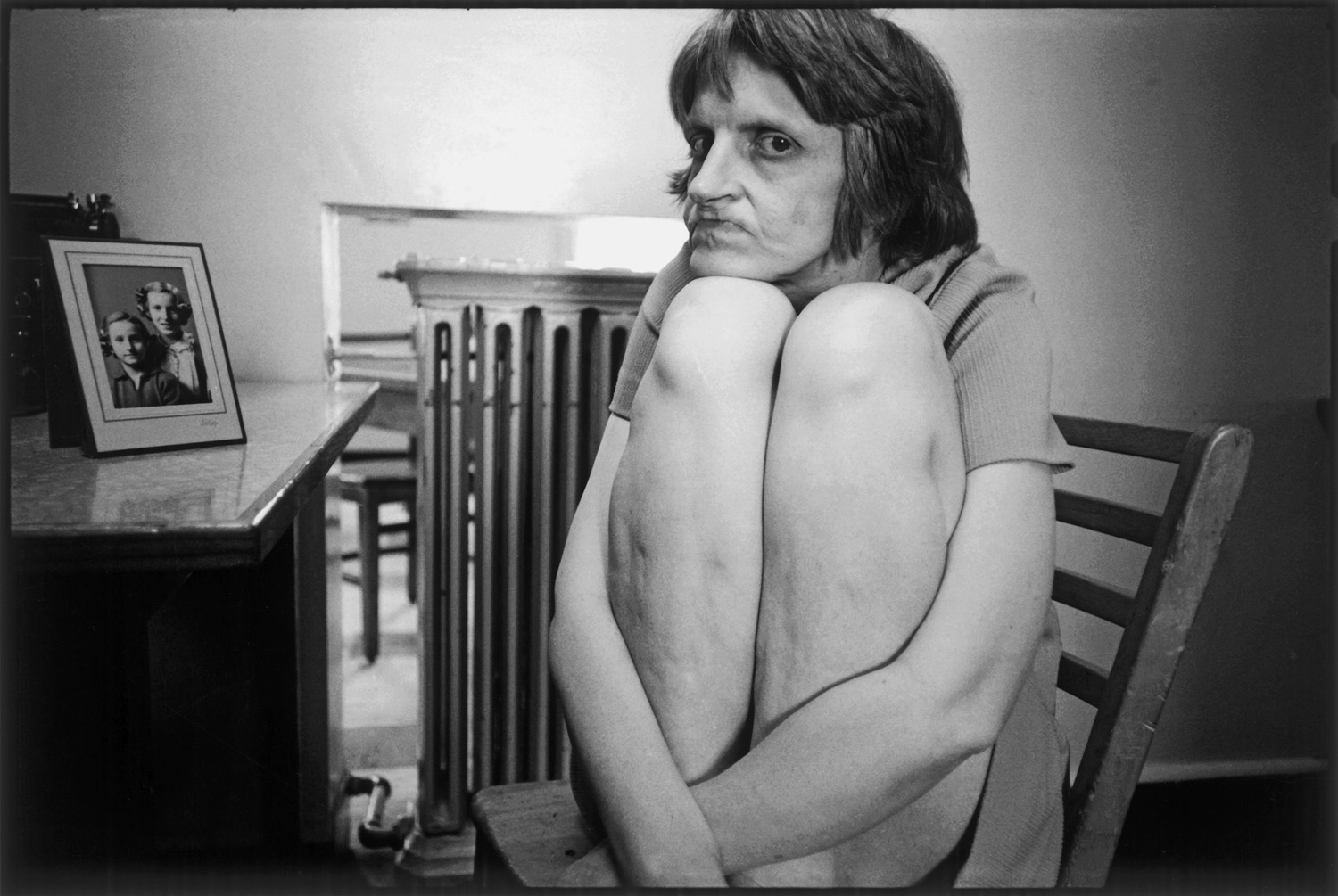

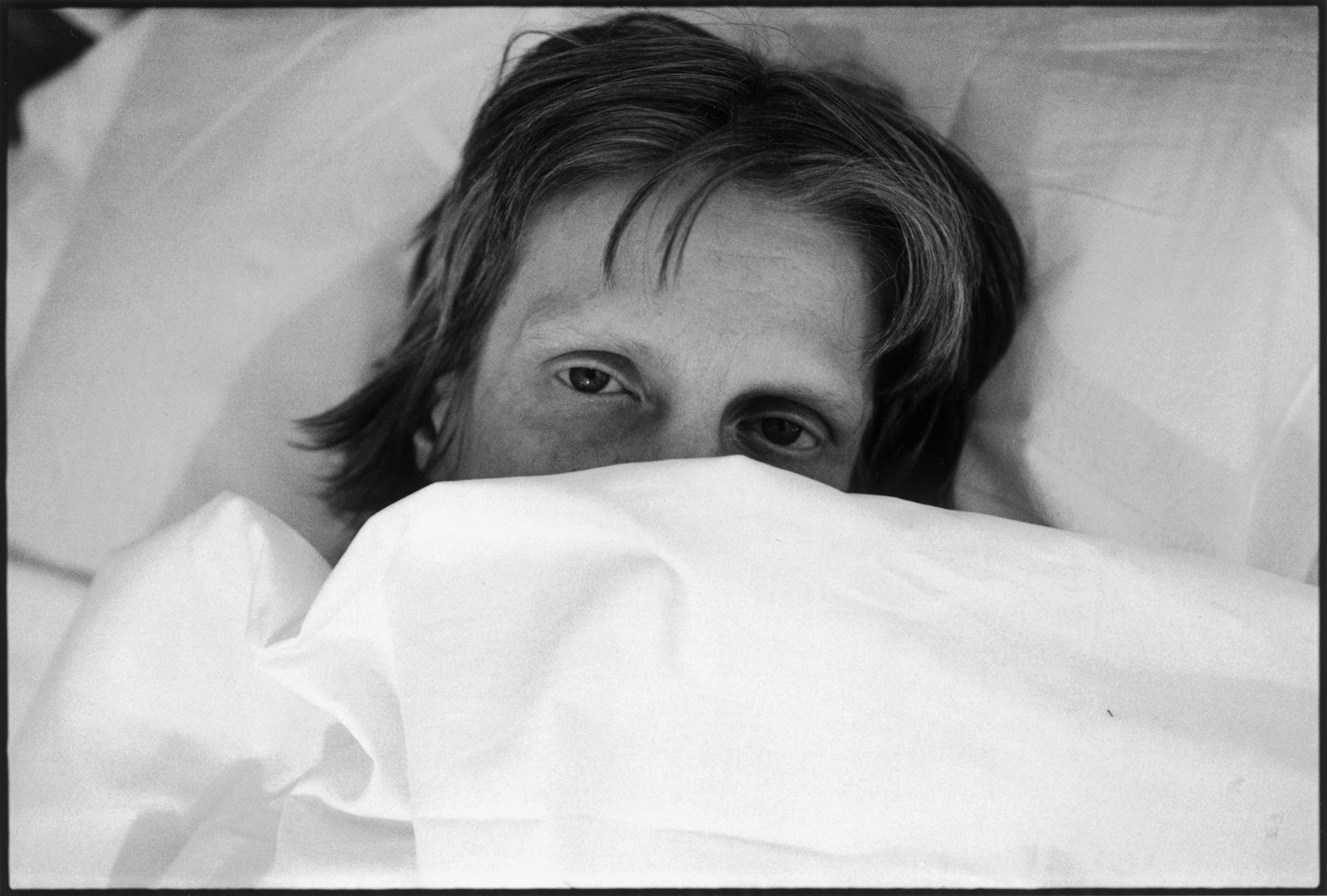

Employing a social science method known as ‘participant observation,’ Mary Ellen and Karen enmeshed themselves in the daily goings-on of the residents, capturing anything from arts and crafts classes to the immeasurable horrors of electro-shock therapy. Even more groundbreaking than their sensitive approach was the pair’s dedication to consent and patient autonomy. Each of the residents chose whether or not they wanted to participate in the project, and some selected their own pseudonyms. This underlying sense of trust and familiarity reveals itself through Mary Ellen’s intimate shots of the women bathing, embracing, or staring longingly out the window, yearning for a world beyond the metal grates.

“One of my favorites is the photo of Beth and Mona together, because not only is it telling of the institution’s environment, but also their unique personalities,” Gaëlle says about a picture depicting a couple confined in the ward. Captured amidst a hydrotherapy session, one patient, Mona, stares defiantly at the camera, hands on her hips. She’s standing protectively in front of her wide-eyed partner Beth, whose body language is stiff and reserved. “You can immediately recognize the differences between the two of them and understand that these are people with their own individuality and character. That was very important to Mary Ellen.”

When they weren’t working in the ward, Mary Ellen and Karen left behind polaroid cameras and tape recorders for the women to put to use, granting them a right usually denied to those who’ve been involuntarily institutionalized: the freedom to shape their own self-image. “The idea was to give a voice to these women, to reverse the power dynamic, to give them a presence,” Gaëlle explains. “They had the opportunity to put on makeup or choose their own clothing, for example. It gave them agency in their representation.” Polaroids showing the patients smoking, laughing or simply posing with friends demonstrate the duality of life in a psychiatric facility, the emotional limbo of an experience that seemed to have no end in sight.

A similar sentiment underscores the curation at the Image Centre, featuring photographs grouped together by pseudonyms — Laurie, Carol S., Mary Grace, Suzie and so on – in order to let each of them stand out. Additional archival materials collected throughout the project range from recorded conversations between Mary Ellen and Karen, as well as conversations with the residents, to letters or drawings the women made, signed patient waivers, contact sheets, and press coverage. “They treat you like you’re no good,” reads one wall quote from a patient named Tommie. “What they’re saying is, you’re in a mental hospital and therefore, you’re stupid, you’re an idiot, you’re dumb […], you’re ugly, and you’re no good, and you don’t belong in this world..”

Ward 81 closed in November of 1977, when it was combined with another wing of the hospital to create a co-ed treatment facility. Still, the project came at a pivotal period for the discipline of documentary photography, as critics questioned the fine line between exploitation and empathy, especially regarding images of disenfranchised populations. “This was one of her first big projects, but the same themes were present throughout Mary Ellen’s whole career. She was constantly dealing with vulnerable people, especially women,” Gaëlle tells me. “How do you find the best approach to show the necessity of the situation, but also remain respectful? How can you do justice to the people or problems represented? It’s about recognizing them without othering them.”

Mary Ellen distinguished herself from a controversial history of aestheticizing patients in mental illness facilities by eschewing false notions of objectivity and infusing her photographs with tenderness and soul. She cared deeply about her subjects, not only during her weeks in the ward, but long after she left, carrying their stories with her wherever she went. Her unflinching images continue to have an impact nearly 50 years later, preserving the women’s humanity at a time when the state had attempted to strip it away.

“The women of Ward 81 are tattooed on our memories. We know that for the rest of our lives we will often dream about them. We will be surprised to wake up in a bed without straps or locks, and to be able to see out windows without wire barriers. And whenever anyone says ‘That’s bullshit,’ we will be reminded of the inmates and their emotional directness, their honesty, and their intolerance for phoniness,” Karen wrote in Ward 81. “We identify with the fragility and the strength of these women we came to love, these adopted sisters of ours. They are women we might have been or, women we might one day become.”

Credits

Images © Mary Ellen Mark, courtesy of The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation/Howard Greenberg Gallery