While on a Smithsonian Fellowship in Washington DC in 1974, Marc H. Miller set up a booth at a handicraft fair near the mall and posted a sign that said, “Conceptual artist looking for participating people.” A young art therapy student from Amsterdam named Bettie Ringma (1944–2018) walked up. “She was a photographer who had just separated from her husband, a Dutch diplomat,” says Marc, who made his first photograph of Bettie just minutes after meeting her.

Things clicked very quickly, and they began to collaborate. In 1975, Marc and Bettie began the Paparazzi Self-Portraits series. Using the new Polaroid SX-70 instamatic camera, Bettie posed alongside luminaries like Angela Davis, Susan Sontag, and William S. Burroughs while Marc snapped the shot. They took the project to the legendary New York music venue CBGB in 1976 during the height of punk for the series Bettie Visits CBGBs, where she posed alongside Patti Smith, the Ramones, Talking Heads, and Richard Hell.

“Bettie was a great communicator; she could literally talk to anybody since she spoke five languages,” Marc says. “She was an open person who liked people. Nobody was beneath her. Everybody was entranced in a way. She was very attractive and had very welcoming blue eyes. She was a good listener, and everybody felt comfortable talking with her. But she had no fear of rejection; nobody was above her either.”

Marc and Bettie continued to build and expand the collection, taking the project to Washington, DC, in order to photograph politicians. “It required an element of trust on the part of the people, especially if they were in the public eye,” Marc says. By 1979, Bettie had returned to Amsterdam to finalise her divorce, and Marc joined her on the journey. With her settlement, Bettie purchased a houseboat docked opposite the Anne Frank House. Marc brought a smaller version of their landmark 1978 exhibition, Punk Art, to Amsterdam and set off a firestorm when he told the press there was no punk in the Dutch capital. “Within about a month of arriving, we were on the front page of the newspaper,” Marc says. “Of course, we said all the wrong things, and everyone hated us.”

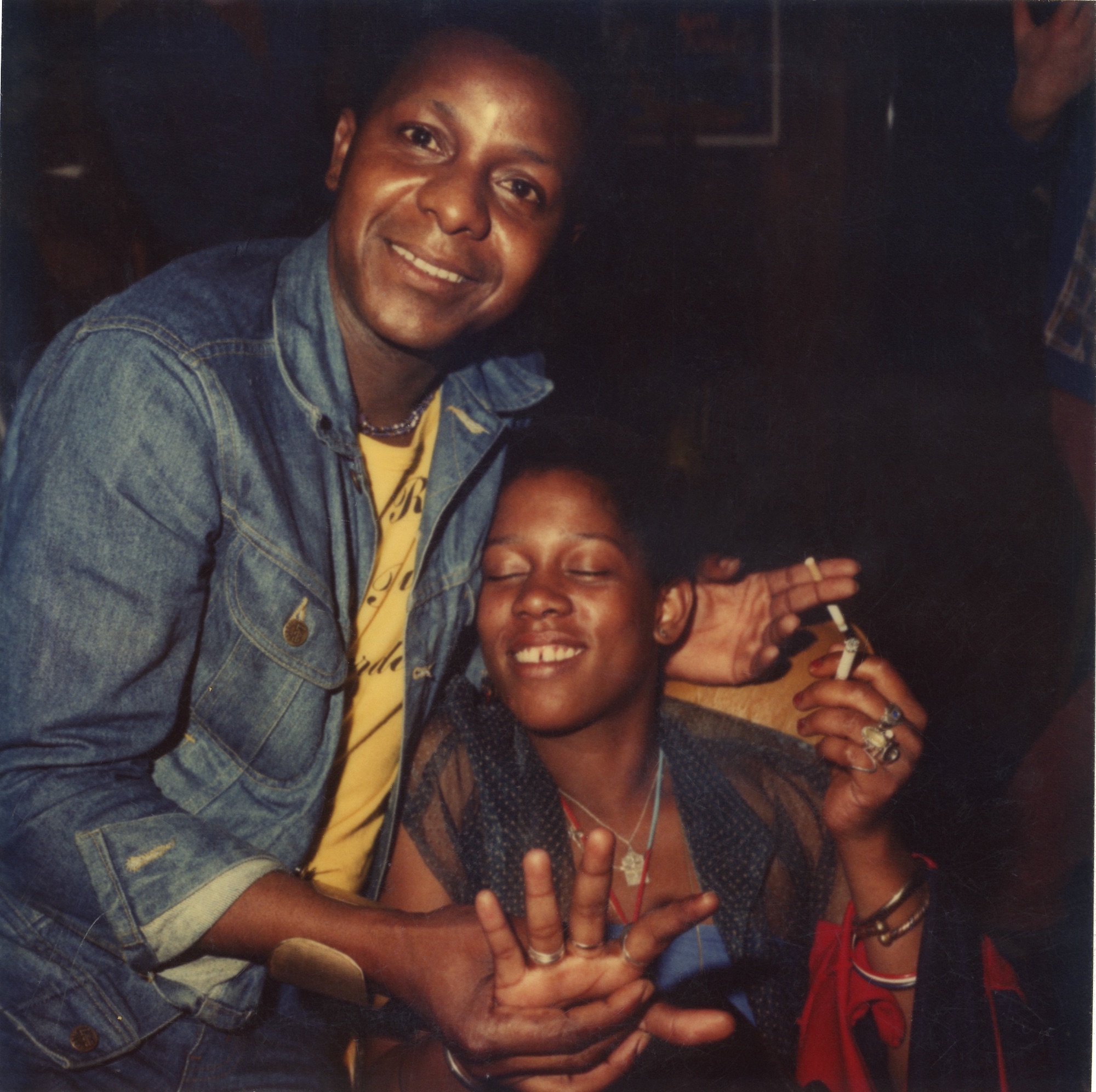

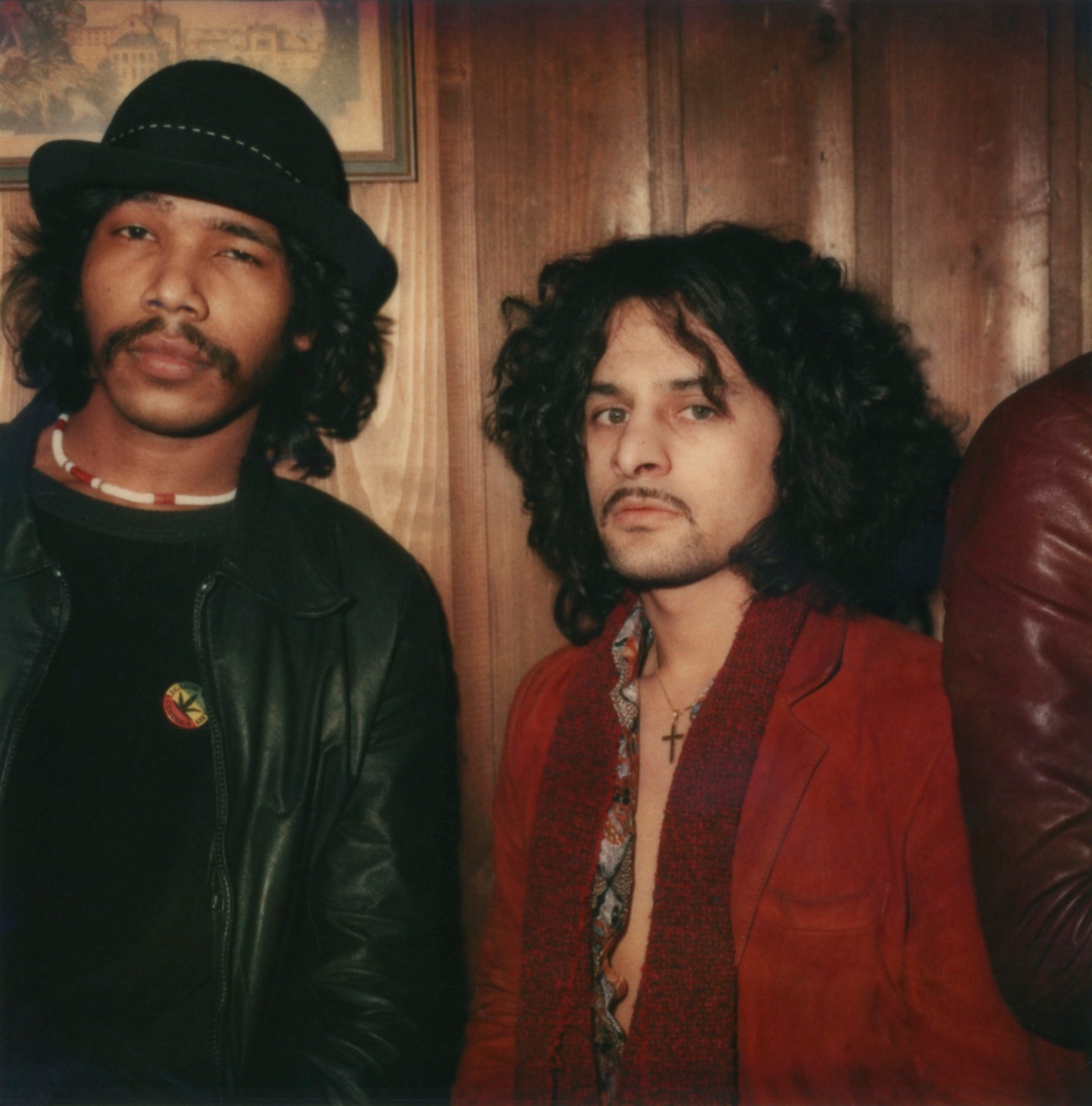

But that didn’t stop the dynamic duo from making history in Amsterdam. Finding ways to support themselves in a new city, Marc and Bettie drew inspiration from the New York hustle. Remembering a Polaroid photographer who peddled snapshots made at Coney Island, they decide to hit up the Red Light District. Four or five nights a week, they made the rounds, photographing anywhere between 30-100 people a night at the soccer bars, gay bars, discos, Turkish cafés, old-school bruin cafés, and tourist traps.

Collected in the forthcoming book, Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam, 1980 (Lecturis), Marc revisits the archive for an expansive look at their practice, which provided an important bridge between present and past. As roving photographers, Bettie and Marc regularly made the rounds, building up a regular roster of workers and regulars. They got permission from bar owners to work the room and sold photos for six Dutch guilders (appx. £3) each.

“It’s a certain type of personality that wants their picture,” Marc says. As it so happened, Bettie and Marc tapped into a deeper cultural touchstone: the longstanding tradition of Dutch tavern portraits, which dates back to the work of 17th-century painters like Adriaen Brouwer and Jan Steen. As an art of the people, these madcap scenes of raucous delight were the snapshots of their time that challenged the prevailing morality while simultaneously preserving idiosyncratic characters engaged in lascivious escapades.

By the turn of the 80s, Amsterdam was in transition, as reflected in the bar girls, patrons, and workers of Marc and Bettie’s photographs. “Change was taking place in Amsterdam,” Marc says. “People from remaining colonies like Suriname were offered Dutch citizenship, and there was a big influx of people to the city. At the same time, it was [a time of] gay liberation, gay bars, and women-owned bars. We ended up with a very full picture — because they wanted a photo.”

Then inspiration struck. “We knew that Polaroid often supported artists, so we told them about the exhibition, and they gave us a case of film with 500 shots so that we could take second shots for the exhibition,” Marc says. In 1980, sizzling weekly magazine Nieuwe Revu published the photographs on a multi-page spread. “We used to say sex, soccer, and socialism was their beat, and that article transformed everything for us,” Marc remembers. “A few people would follow us, calling our names like a weird celebrity. In the article, we also announced we would be returning to New York, and that’s when a couple of other Polaroid photographers started popping up. Today in Amsterdam, there are still Polaroid photographers combing the bars and restaurants — and we were the first.”

‘Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam, 1980‘ (Lecturis, May 2023) has just launched a crowdfunding campaign for the book, now through early April 2023.

Credits

All images © Marc H. Miller and Bettie Ringma