“It started really small, like all scenes do. Clubbing in London was a closed shop before house music — you’d have rare-groove nights, hip-hop or soul nights, maybe parties in warehouses. There weren’t many opportunities to do something new,” says DJ Danny Rampling, who in 1987 had a graveyard slot playing soul on pirate station Kiss FM, but felt restless.

On a holiday to Ibiza in the summer of that year, with friends Nicky Holloway, Paul Oakenfold and Johnny Walker, Rampling got turned on to the mix of house tracks and euphoric pop now known as Balearic beats, and returned to London with almost evangelical fervour, playing the new hybrid on his show and immediately finding a larger, more hungry audience.

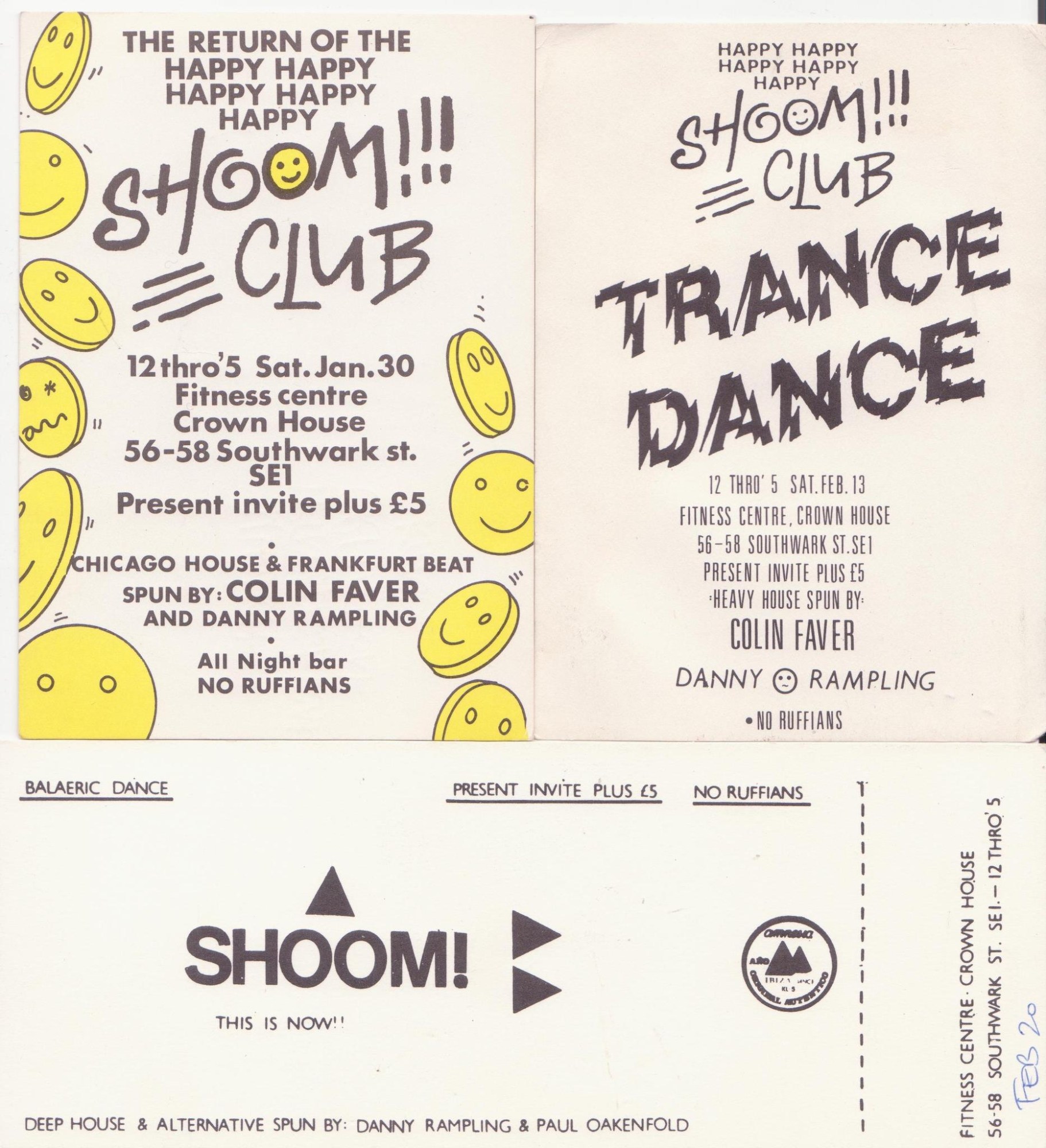

“Youth culture was very divided before acid house came along,” he remembers. When he and former partner Jenni started their club in December 1987 — with a sound system installed by future DJ star Carl Cox and New York house legend Tony Humphries sharing Rampling’s decks — they opened the door to a new kind of nightlife in the capital. Rumoured to be named after the sudden rush of coming up on a pill — “Shoom!” — the club was mobbed from the outset.

“It deconstructed class divides, social and sexual taboos — and the walls came tumbling down,” Rampling says, keen to emphasise social changes before chemical ones. This whole wave of optimism and positivity brought a lot of people together. The collective spirit was what everyone loved about it. Let’s not forget, the economics of Britain in the ‘80s were very much like now, with a dominant fighting and drinking culture. We got a lot of those people to ‘lay down their weapons’ at our club and meet in an atmosphere of positivity and DiY culture. We created our own opportunities and that’s what people loved.”

Fittingly, Shoom’s first i-D mention comes barely a month after it opens, an amazed, throwaway line in the nightlife column: ‘meanwhile, 200 people are getting turned away from Danny Rampling’s new night in a south London gym’. Rolo McGinty of the Woodentops, whose indie track Why Why Why blew up as a Balearic anthem long before Primal Scream collaborated with Andy Weatherall, came to the first night. He’d met Frankie Knuckles while touring the US and experienced the rise of house music as a tidal wave. “I was excited to see so many people there, the sheer energy of it,” says Rolo today. “Usually my band was not connected with any other styles of music going ‘round, yet here we were, invited in and welcome, but the key thing was this new form of electronic music, like science fiction on a dancefloor!”

By spring ‘88, acid house and techno were on the ascendant, the ecstasy-fuelled raves of the Second Summer of Love yet to trouble tabloid editors — that came later. “You could start your weekend on Wednesday and carry on to the next Wednesday. There were suddenly all kinds of things going on in London,” Danny Rampling laughs. “I was happy doing my club. but maybe I should’ve played those orbital parties too?”

As the club grew, so did the crowds – but they were kept in check by an admission policy friendly to original regulars regardless of origin. South Londoner Barry Ashworth — now head gunslinger in Dub Pistols — was working in film and holidaying in Ibiza; when he found his way to Shoom, young men from nearby estates danced beside him, done with the postcode war that marked their teenage years. All remain friends today. “One of our mates turned up with his own portable podium, painted in smileys, and stood atop it for the whole night!” Saskia Lamche, then a CSM student, now the owner of north London boutique Diverse, says the silliness kept Shoom real. “At the end of the night, they passed out oranges and everyone formed a circle, eating them as we chanted ‘Shoom! Shoom! Shoom!’”

For a mere fiver, you could spin the night away next to dressed-down popstars on the down-low, classical dancers after curtain-fall, incognito fashionistas, football hooligans who’d set their beefs and machismo aside after taking ecstacy, future popstars following the lead of NME bands widening the spectrum of their sound, and women who found a place to lose themselves safely in music. “Shoom was my first real clubbing community,” says naturopath and former magazine editor Helen Mead. “It also was my doorway to somewhere ‘higher’ – a state I could fully inhabit and take into the rest of my week.” Everyone came together in XL sportswear and dungarees, smiles on their faces to match the symbols on badges and wall-hangings around the club. “The first time I went, my friends warned me it wasn’t like the West End, so leave the Westwood at home,” laughs author and lecturer Terry Newman, at the time a UCL student with high-fashion tastes, now married to a fellow regular and still tight with many others. “People there became family to me.”

Danny Rampling is still keen to mingle the organic with the futuristic; at this weekend’s party, virtual reality mingles with decades-old club classics and what he hopes is a freaky family reunion; in 2018, Irvine Welsh’s Ibiza ’87 will tell the story of the south London dance explosion with Rampling’s help. “We all had an amazing time. It was a unique period and we were lucky to be at the forefront. It brought so many people together and gave us opportunities — let’s face it, nobody was gonna give us that freedom, so we took it!”

Shoom 30 is at Bankside Vaults, London, Friday 8 December. Images courtesy of Danny Rampling.