“A door opening is the beginning of many great stories,” Miles Aldridge says, when asked about an image of the artists Gilbert & George opening the front door of their house at number 12, Fournier Street. The collaboration with Gilbert & George forms one third of Miles’ new exhibition, (after), recently opened at London’s Lyndsey Ingram Gallery.

Storytelling is at the heart of much of the work in (after) — which transforms the work of sculptor Maurizio Cattelan and painter Harland Miller, alongside Gilbert & George, into the raw material of Miles’ photographic work. He creates surreal images of Maurizio sculptures confronted by an otherworldly nude female or imagines Gilbert & George in a chamber drama, playing host to a mysterious androgynous visiter. Harland Miller’s large scale paintings of book covers are turned into paperbacks and found in the hands of kitsch 50s pin ups. “I think it’s a mark of great confidence, and beautiful modesty, for an artist to let another do this to their work,” Miles adds.

Each series threads a cinematic narrative throughout, but it’s also a story about collaborations and the medium of photography itself; forgoing traditional photographic techniques and turning to screen prints and the Victorian process of photogravure to create the images.

On Maurizio Cattelan… “Like all good artists he’s managed to keep that childish enthusiasm for everything.”

“Working with Maurizio began simply, as many things do, when you look back on them. It turned out, via someone I was working with, that we were both mutual fans of each other. So they put us in touch. I got an email from Maurizio, saying he loved my work, and he added something like ‘In the sea of images it’s still possible to create meaningful work’ — referring to Instagram and the endless unstoppable diarrhea of images.

I’d been doing a lot of work for Italian Vogue, working in a very slick advertising aesthetic but trying to convey some kind of anxiety or unease with it, questioning consumerism. It was all down to Franca Sozzani, who really trusted me to create the work. It was important not to make it too dark and keep it a little mysterious. We didn’t have conversations about what something meant, it didn’t need to be said with Franca, that’s why she was a great editor. I think my style is very similar to Maurizio’s, with Toilet Paper especially, which used a similar style to create images that seemed to be saying that consumerism and modern culture is attacking us. Rather like Andy Warhol’s Car Crashes, the things we covet, kill us.

I’d grown up with an older sister who was a successful model. When I got my chance to be a fashion photographer I didn’t want to promote the idea that being rich and beautiful means you are happy. Life and the world isn’t like that. That’s what I wanted to say with my Italian Vogue work. You just have read five pages of a newspaper to know the world isn’t the way magazines present it.

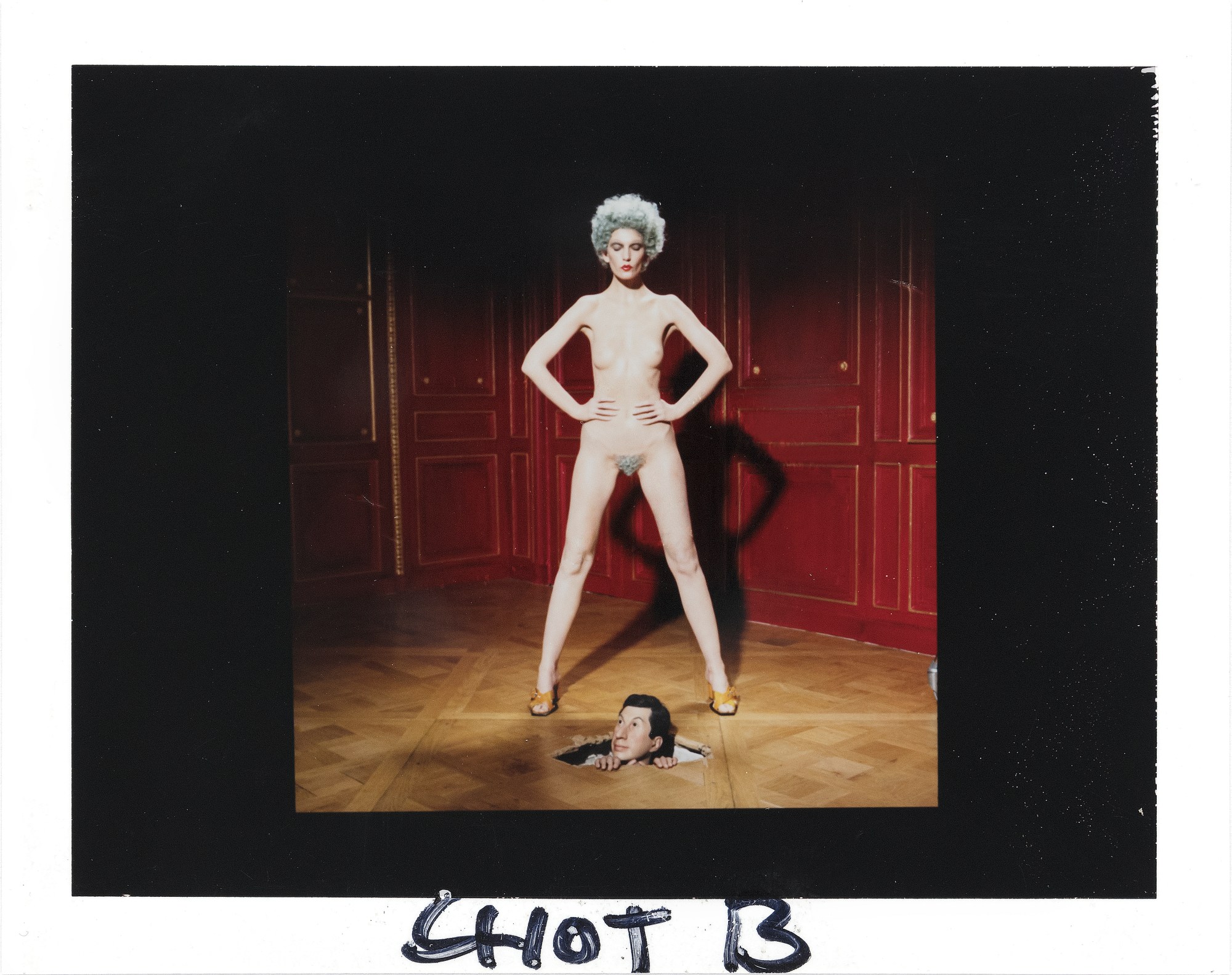

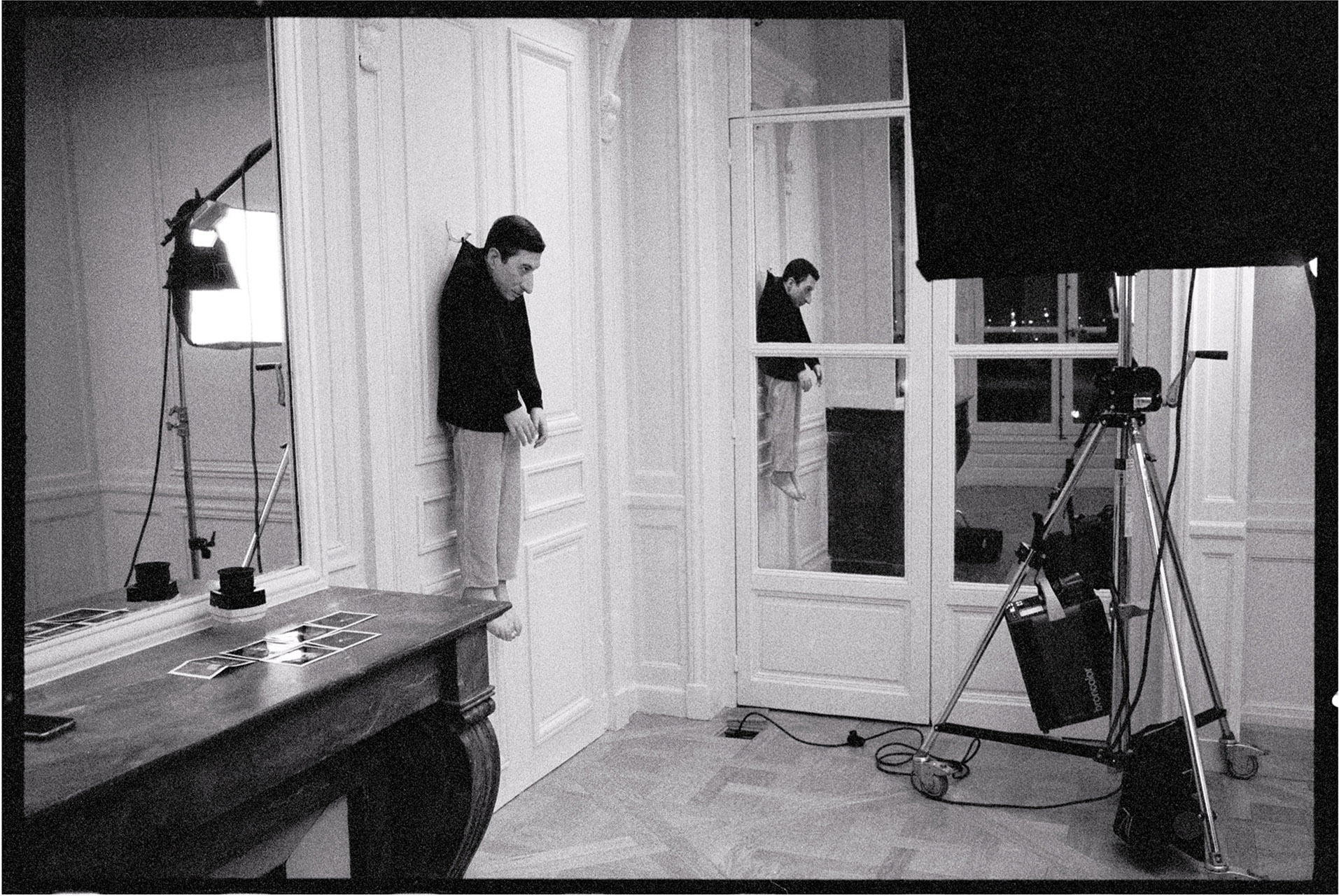

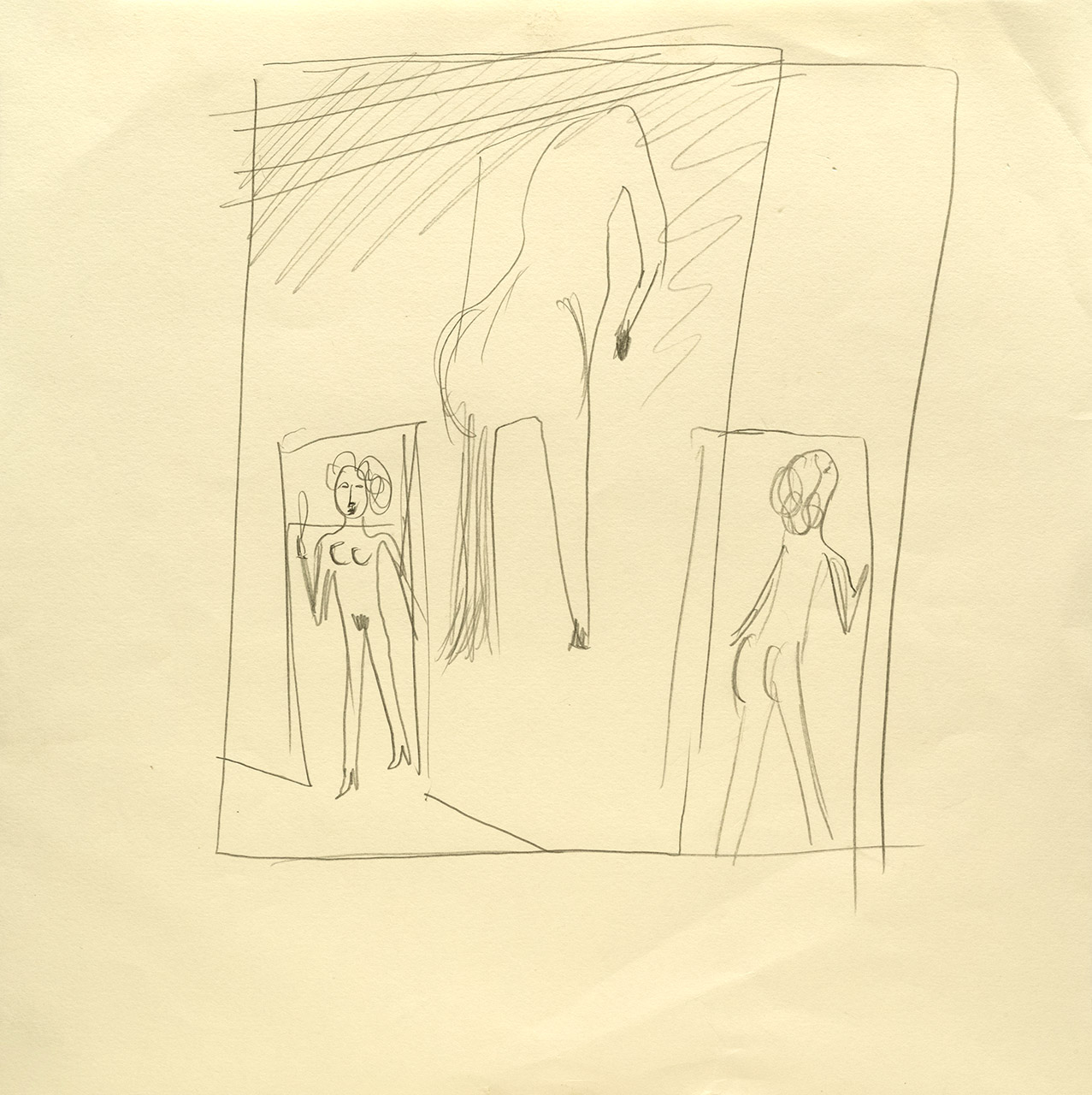

We went back and forth talking about photography over email, talking about starting to maybe do something together. One day he sent me an email and said ‘Look I’ve got a show opening in Paris which I think would be a great background to your photography.’ The exhibition was full of all his famous sculptures, and I had the idea to have these quite kitsch female fury’s confronting them; their modernity confronted by the classical female nude.

So we planned to meet at 7PM, as the museum closed, and work through the night. Maurizio had a little bed set up in one room and he’d sneak off and nap occasionally. We worked right through till the museum opened in the morning. He was kind of obsessed with photography, talking about lenses, film, processing, printing, the lights we were using. Like all good artists he’s managed to keep that childish enthusiasm for everything. He was very free and easy to work with, very inquisitive, and kind of let me do my thing, putting some ideas in too.

Maurizio was the first artist I worked with, and from there it became not just about the relationship with the different artists, but also about my relationship with photography, and the different processes and possibilities of the medium.”

On Harland Miller… “I asked him and he said it was doomed to failure but he was happy to see my try.”

“I’ve known Harland for about 20 years. When we first met Harland was trying to be a novelist and I wanted to be a filmmaker, trying to find a way into Hollywood. I started taking pictures of Harland before I was really a photographer and before he was a painter. His paintings are all about writing — without the titles they would, I suppose, be a form of abstract expressionism, blocks of colour, paint and texture. With the titles they become whole I think. The humour in his work is undeniably British. Slightly kitchen sink, full of innuendo, but also very profound, they strike the imagination.

I sat in the cathedral-like space of the white cube looking at Harland’s works, wondering what I could do with these paintings that reminded me of so many things about my own childhood. One of the points of art is to play and to see where it leads you. In a way that was very much how I saw this project unfolding. I loved the idea of doing something as simple as turning his fake book covers into real books, it’s so obvious. I think my naivety carried it through. I think you have to try and retain that childish simplicity. My father was a great artist but he was an eternal child and his artistic logic was like a children’s storybook, it was really strange, really charmingly naive. We tend to live with such a high level of pretension and critical theory that something so obvious wouldn’t seem right.

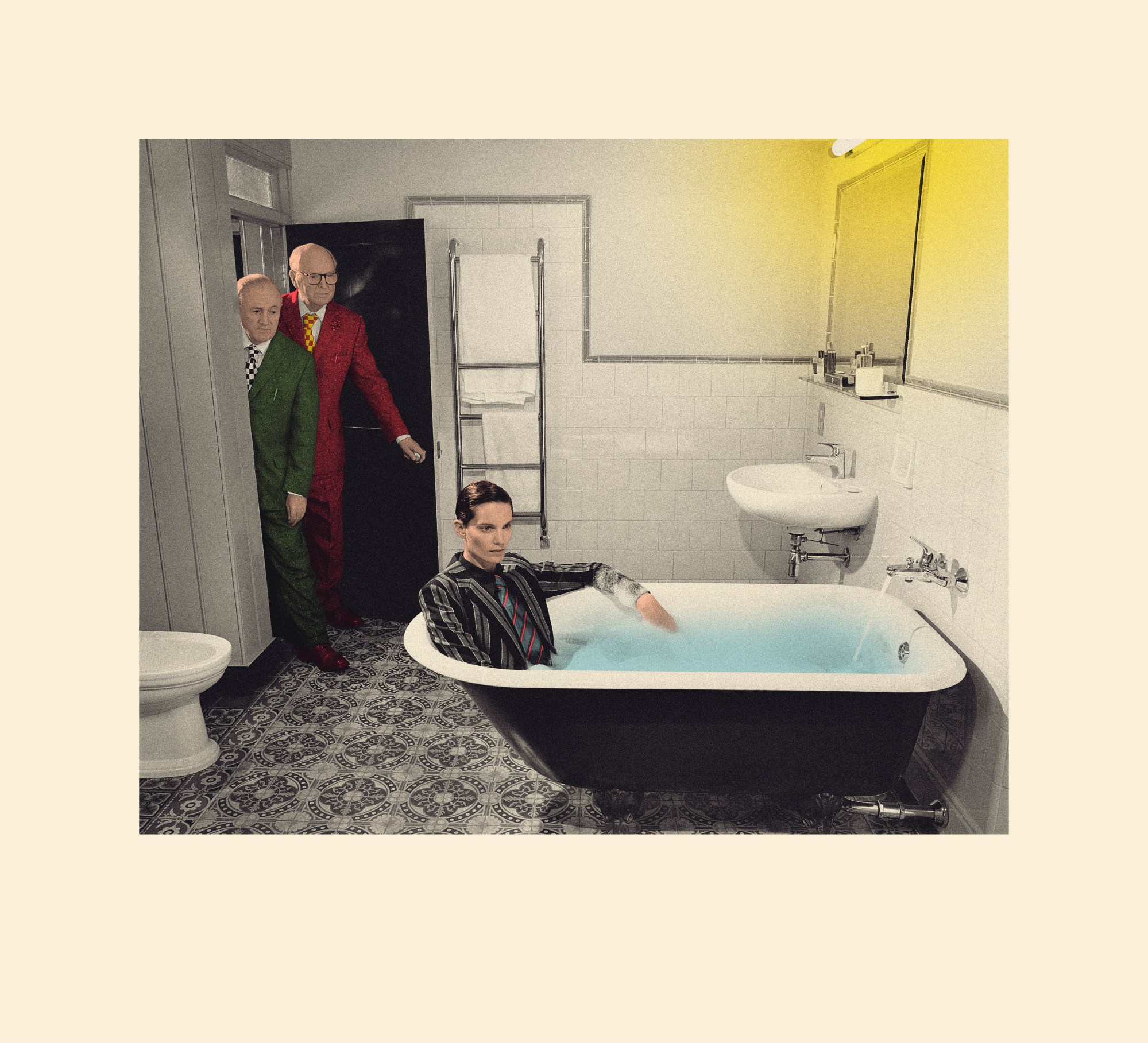

So I asked Harland, and he said it was doomed to failure but he was happy to see my try. So I turned the paintings into book covers and strapped them onto my own paperbacks, because I needed them to feel used. Armed with these paperbacks, I started to think about them in cinematic terms, within narratives. Scenarios involving a protagonist and a book; some came to mind instantly; the bath is a classic, the way water soaks into the pulp of the pages. Then I imagined Anna Karina from a Jean Luc Godard film, an open novel in her hand looking out of a rainy window, full of melancholy and beauty. Then reading in bed, or at the table, I wanted to get the scene and setting in. The hideous textured curtains from the 60s and 70s that both Harland and myself were subjected to as children. I mean my father had painted the house in various psychedelic colours in the 60s, and my mother added to this headache inducing colour scheme by bringing William Morris textured sofas and textile surfaces. One room was decorated like a Union Jack, which was very much the thing you’d do in 1966. I wanted to capture that kitsch in the images.”

On Gilbert & George… “I love the idea of the camera being used as a fictional device, as a way to create a story.”

“I’d photographed Gilbert & George before and the thing that really stayed with me was that when I knocked on number 12 Fournier Street, there was this definite sense of preparation going on behind the door. The sound of moving and arranging. It went on for about seven minutes. Then the door suddenly opened. George stepped forward with an outstretched hand, and Gilbert hid down the corridor at a really interesting angle, he could be seen but wasn’t totally revealed. It was perfectly choreographed. When I considered the idea of doing a project where they would be the stars I knew wanted the first shot to be the greeting at the door.

A door opening is the beginning of many great stories. That entering of a new world. I love the idea of the camera being used as a fictional device, as a way to create a story, a cinematic conceit. So I asked myself ‘who’s arriving’, that’s the beginning of the plot. I initially thought of some kind of crazy aunt arriving to spend the weekend with them and have tea and go cycling, do those kind of Edwardian things. But the idea evolved into the mysterious androgynous guest. It needed to be open; the power of photography comes from the things that aren’t easily explainable, that have that inscrutable mood.

I printed the images using a Victorian-era process called photogravure, where a photograph is being transferred to a metal plate via etching, and then it’s inked up and goes through a press, and the image comes out. I was exploring different print processes through these works, I wanted to use something different — the images with Harland are screen prints, for example. I wanted to use processes that weren’t necessarily light-based. I didn’t know any contemporary photographers making photogravures. It used to be a very common way to distribute images.

I think the value of photography itself is being questioned at the moment. If you just think about how many photographs we consume a day, how throwaway they are. So this more precious, hand made form of photography, was a response to feeling photography was being undermined.”