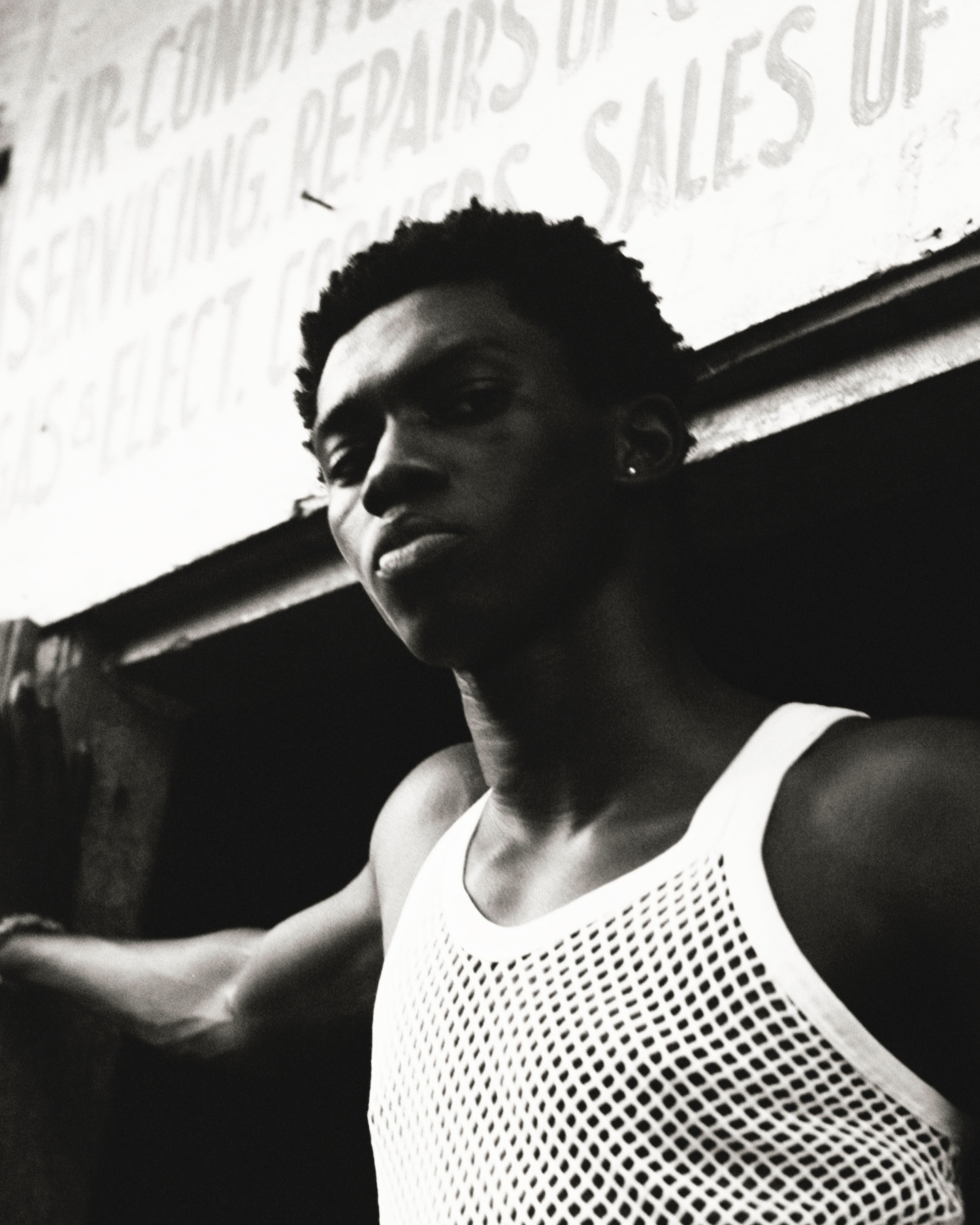

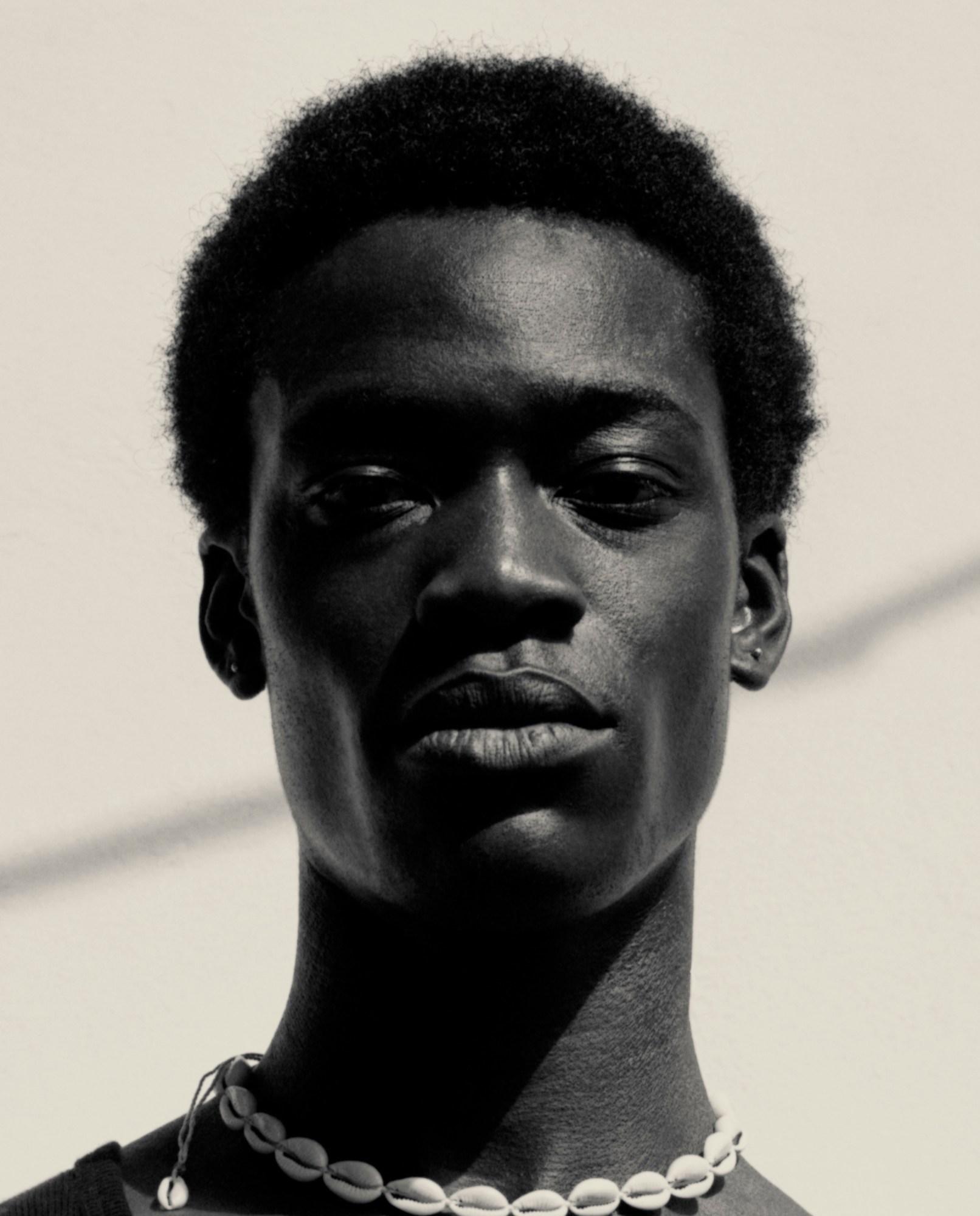

The Man Who Was Almost a Man is the title of a short story by author Richard Wright, but it could also be the theme of Belgian-born photographer Kwabena Sekyi Appiah-nti’s work. After studying web design and marketing, Kwabena focused on photography, a practice he’d developed as a teen, snapping his skater friends with his mom’s analogue camera, and later photographing nightlife scenes. He started freelancing, with his photographic practice crystallizing around Ghanaian culture — a direct link to his patrilineal heritage — and casting a sensitive gaze on Black identity. His work was nominated for the Foam Talent program and several of his visuals were included in the 2022 Photo Vogue festival.

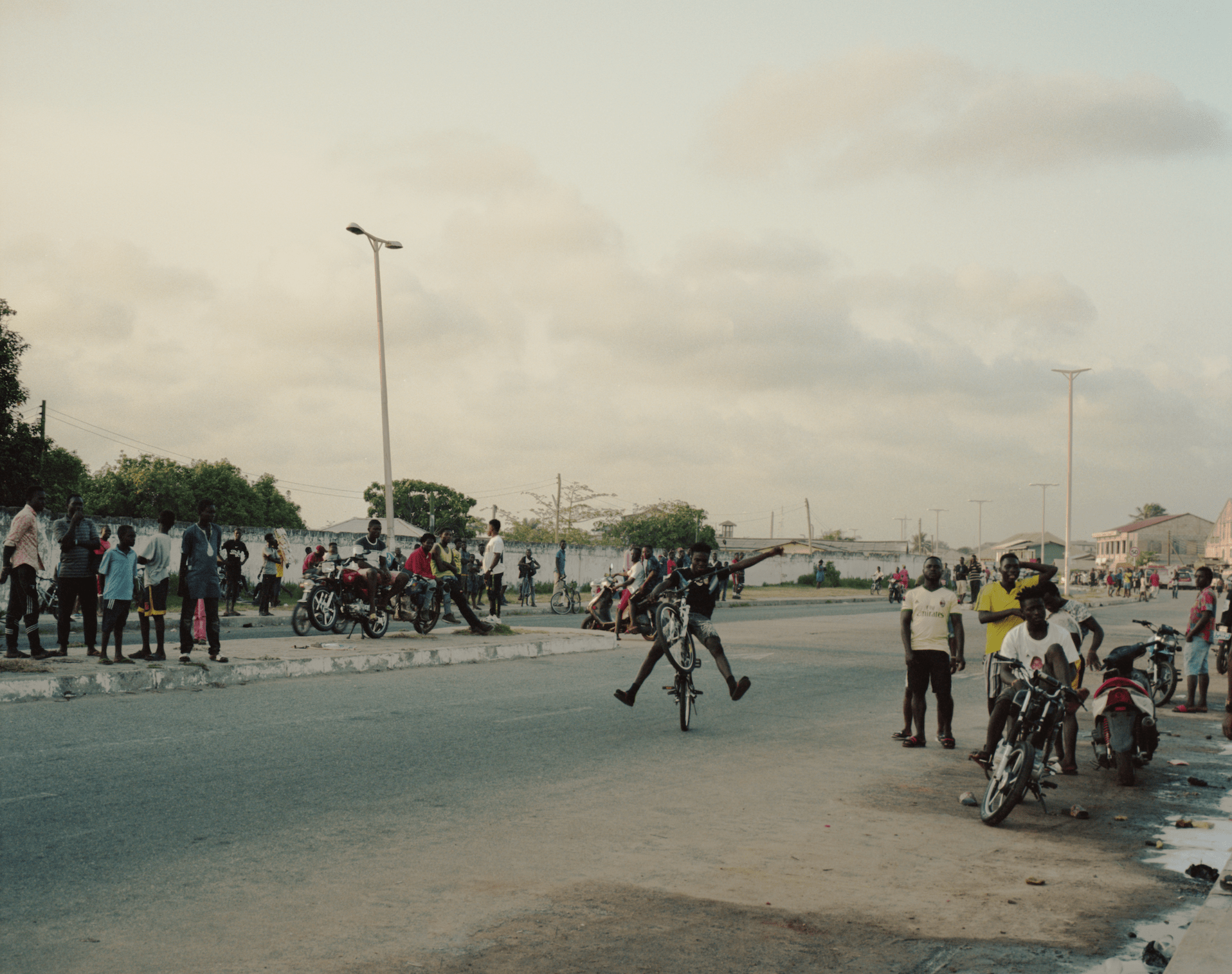

His vision examines the nature of Black manhood and boyhood, but chooses to showcase its elegance over its pains. The social power structures that have looked askance at Black boys and men are cast aside, elevating his figures into beautiful silhouettes. His two ongoing preoccupations are Golden Boy, a series about contemporary Black masculinity, and Bikelife, a series about off-road motorized adventures and the community around them.

We spoke to Kwabena, who is based in Amsterdam, about traveling widely, blending fashion photography with documentary and the thrill of being on a bike.

When did you know you wanted to become a photographer?

While I was freelancing, at one point I was like: What is my signature? I love things that revolve around boyhood. When I look at my favorite movies — City of God or La Haine — they tell the stories of boys growing up. I shot some stuff in Brazil, Suriname; I went to Ghana for the first time. I submitted that work to the FOAM Talent program, and I got selected. That was my first step into seeing my work not only as documentary or fashion photography, but in the context of a gallery or a museum.

When I was looking at your images, I hadn’t really considered them as documentary per se, because there’s such beautiful drama to them, bleeding into fashion photography. Can you talk more about how you categorize your own work?

Some big inspirations are, for example, Alex Webb, who does documentary stuff, but his work looks so good that it almost looks staged. Then you have people like Deana Lawson, or Dana Lixenberg, who make documentary work in the sense that it’s real, but it’s also staged. That’s what I tried to do. You can walk around and shoot — but sometimes, I’ll see somebody surfing, playing soccer or just sitting, and ask, Hey, can I take a picture of you? So it’s a mix. I think that it sometimes looks a little bit fashion because I also do that as my work. You have a little, like, fashion feeling.

When you’re doing commercial work, how does it coexist with your independent projects? Do you have to recognize something in yourself to be able to do it, or does it feel quite separate?

Well, it really depends on the job — sometimes I get jobs that really fit my work. When it fits, I try to make it as close to my personal work as possible. That’s not very often, but when I can, I do it in the casting and locations. With some commercial work, it can be really strict: we need this shot, this shot, this shot… but if I get the chance, I try to create more openness. When I’m in Ghana, I take pictures and we sometimes go to the subject’s neighborhood, we walk around, we just find stuff. We don’t plan it.

Can you talk more about working with the environment? How much are you directing, once you’ve found a setting that you like?

Most of the time, I ask to shoot in a place that’s comfortable for the subject. For posing, it’s really going with the flow, just maybe an interesting wall to stand in front of or lean against: I give them the freedom to try what they want and sometimes I say try this or stand like this, or turn around and look that way. I try to make them as comfortable as possible, because you’ll really see that back on the images — facial expressions reflect if they’re comfortable or not.

I still want to go to a couple of countries to shoot more; I’m working on getting some arts funding to make the trips.

How do you determine what destination will be a good complement to your existing work?

Well, I’ve been in South America, West Africa, but I haven’t been in the Caribbean or America. I haven’t been in a Black Muslim country yet. I’m like, How is the culture different and how do you see that in the images? What I’ve noticed a lot with traveling, it’s kind of the same everywhere. And that’s what I think is interesting, and what I try to highlight: we’re more similar than we are different.

Would you say there’s an anthropological aspect to work, this idea of surveying these different territories and trying to figure out what overlaps?

No… For me, imagery about boyhood is something that’s missing. Or it’s often in extreme. There has to be something ‘special’ going on before people take images of it. I never saw boys like me in a gallery without a “context.” So, for me, the reason that I’m doing this project was not anthropological but more general interest: how do boys like me live in other countries?

Are there any aesthetics that you would like to explore that you haven’t yet?

I’ve been doing this project now for three years, or maybe a little bit longer. Interests always evolve and change. I’ve gotten more interested in abstract work, with props that relate. I’m still exploring. I want to do more than photography: I want to also experiment with making objects, mixed media, screenprints on fabric, see how the work translates.

For the Bikelife series, is that something that you participate in or are you only chronicling it?

When I began shooting it, I didn’t, but I bike myself now. Not as extreme as they are doing, but I have my own bike and everything. From the observer, I became the participant. I’ve been shooting the bike stuff for a long time, but I haven’t really come out with it. It’s also like something that revolves around boyhood, so I do think it fits in the whole context of my work.

Regarding a bike shoot, how do you deal with speed — how do you capture that in a still shot?

Sometimes I’m on the back of another bike shooting. In the latest shots I’ve done, I’ve worked with flash in the nighttime. It freezes the biker and the bike, but it gives this sense of speed by letting the light flow. I have a lot of portraits of people at bike events. When I go to these meetings, it’s a really nice atmosphere. People are barbecuing, chilling, talking, always really friendly. There’s the really extreme side of it, but I also try to show the people and culture around it. It has grown to a worldwide thing now, in Indonesia, Ghana, Congo… they have their own bike crews, and they’re really connected with each other: the guys from Africa follow the French guys, the Dutch guys. It’s getting really big — but it can also disappear.

Why is there the risk of disappearance?

People go to these industrial terrains to practice driving there, so they don’t mix with normal traffic, but still the police comes because it’s illegal. Sometimes they even send out helicopters. It depends on how hard the government wants to crack down on it. There’s a chance of disappearing because a lot of people are like, this isn’t worth it: getting a fine every time or getting the bike taken away. It’s not a cheap hobby. For average people to go to a racing track, it’s not affordable. They should either make places where they can bike freely, or let them do it in these corners of the city where they don’t bother people.

Given that it’s hard to access, what was the first time you encountered this?

I was creating a concept for a fashion shoot and I was like, I want to try shooting with bikers. I didn’t know that existed over here, but then we went to a meeting and it was like, Oh, this is nice. They let me ride the bike, and I I fell in love with the adrenaline.

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist.