When Hull was awarded the title of City of Culture 2017, it was met with scepticism by the rest of the country (see: understatement). As the long-serving butt of the nation’s joke, Hull is best known as a down at heel, end of the line town with high levels of unemployment, drug and alcohol abuse and teenage pregnancy. What many often fail to realise, though, is that whatever problems the city has faced, Hull has always had a strong sense of culture that’s as vibrant and diverse as the residents at its heart.

Kingston upon Hull, to give it its full and slightly more impressive name, wasn’t always as downtrodden as it’s been known as in recent years. As a major port, it was subjected to an onslaught of devastating air raids during the Blitz of WWII, evidence of which can still be seen in bombed-out buildings across the city even now. Then, just as the place was getting its groove back, the 70s heralded the arrival of shipping containers and forklifts, leaving many of the dockers — who’d unpacked goods by hand up until this point — redundant. The final nail in the coffin was the collapse of the fishing industry a few years later, when men and women who’d grafted all their lives on the docks found themselves out of work. It’s no real surprise that the city — once the world’s biggest port — found itself stripped of purpose and identity in the wake of such a swift economic downturn.

Crisp & Fry, Spring Bank, © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Despite the tough hand it was dealt, at any given moment in the last century Hull has had plenty going for it — particularly when it comes to culture. David Bowie’s Spiders From Mars, Everything But The Girl, The Housemartins (whose line-up included Norman Cook, now better known as Fatboy Slim) and The Beautiful South all found their feet in the city, while poet Philip Larkin is perhaps one of Hull’s proudest exports (that he referred to his adopted hometown as a “fish-smelling dump” is conveniently ignored).

Hull’s Old Town is home to a series of museums exploring its maritime-related legacy, the evolution of the city and the abolishment of slavery at the hand of William Wilberforce, a pioneer of equality who was born and died in the city; while Ferens Art Gallery — where this year’s Turner Prize contenders are currently on display — has hosted major exhibitions featuring works by the likes of Lucien Freud and Leonardo Da Vinci. Elsewhere, the city’s calendar of events include an annual jazz festival, a weekend dedicated to sea shanties (yes, really) and Humber Street Sesh, a day-long music festival made up of local bands that is descended upon as if it were Glastonbury.

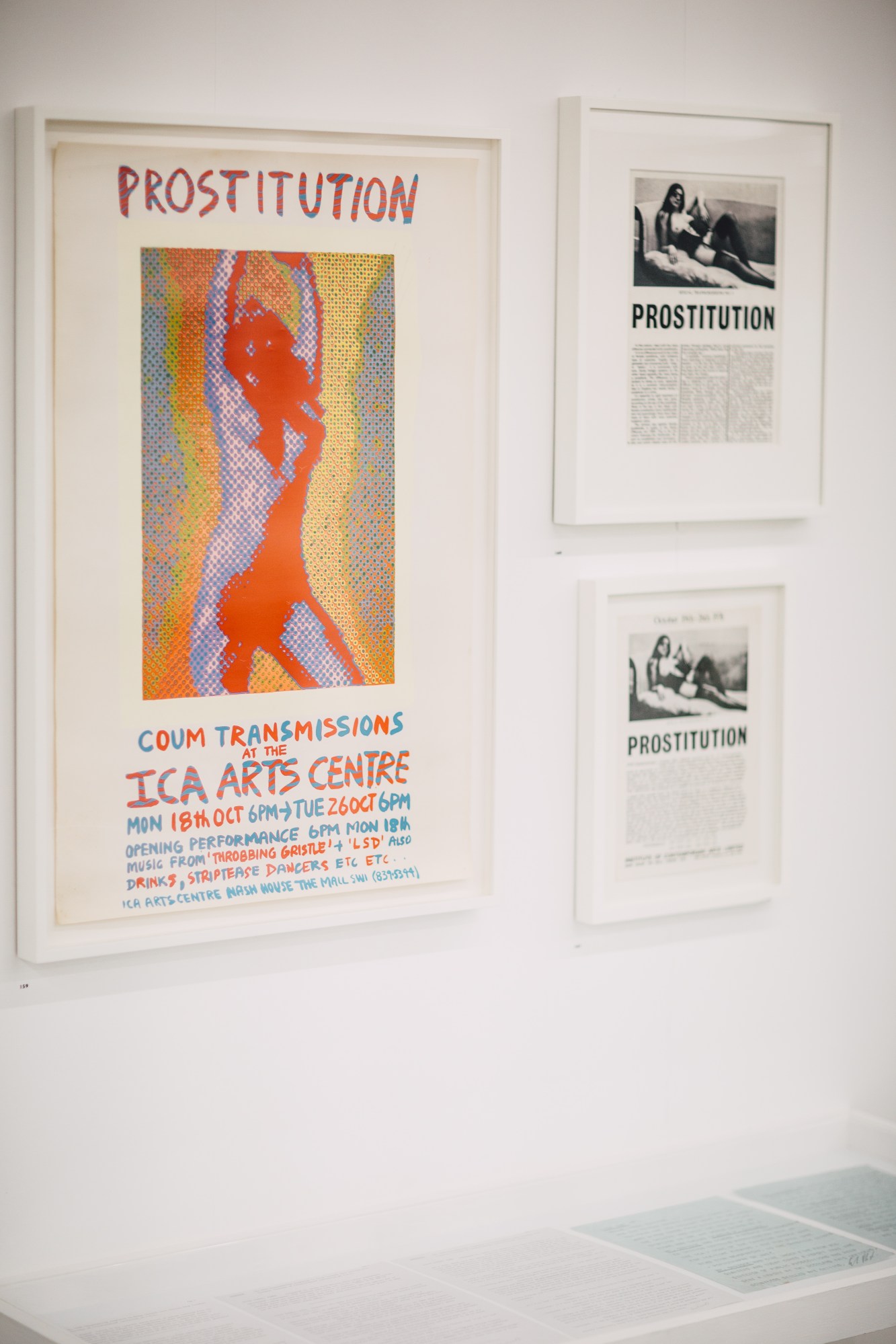

While undeniably much of the city still looks like it has seen better days — the once-thriving, now boarded up high street, for example — it’s perhaps a visit to Humber Street that would dispel any preconceived notions that that’s all there is to Hull. With investment of just over £80m, huge emphasis has been placed on the regeneration of the area overlooking the city’s squint-and-it-could-be-St Tropez marina. A key destination in the cultural calendar, former fruit warehouse Humber Street Gallery opened at the end of last year and in 2017 has played host to a unique line-up of events. The first, COUM Transmissions, explored Hull-born artist and musician Cosey Fanni Tutti and then-partner Genesis P-Orridge’s personal archives, culminating in a live performance from Throbbing Gristle, the progressive industrial band they went on to form.

Rounding off the gallery’s year in no less striking, but perhaps slightly less relentless form, is Hull, Portrait of a City, an exhibition for which Martin Parr and Olivia Arthur turned their cameras on the town and its residents. Martin’s images focus on the culinary heritage of the city, as he photographed the fish and chip shops of the Hessle Road area and, hilariously for those familiar with them, a giant iteration of a patty (a local ‘delicacy’ comprising mashed potato seasoned with sage that’s deep fried in batter — originally for people that couldn’t afford to buy fish).

As surprising as it may be with that on the menu, it wasn’t the food that caught his attention, though — it was the exchanges that took place in the chippies that sparked his interest. “They’re very social places, and everyone that came in stopped for a chat — the people of Hull are very welcoming and warm and very funny — and I found the chip shop was probably the best place to see all of this in action,” he said of his time spent photographing in them. “There was a real sense of pride around Hull being City of Culture this year. Around 90% of the residents I approached were excited to be photographed — but the 10% that weren’t were more than happy to stay and chat about it anyway. It was really great to see the city seemingly invigorated.”

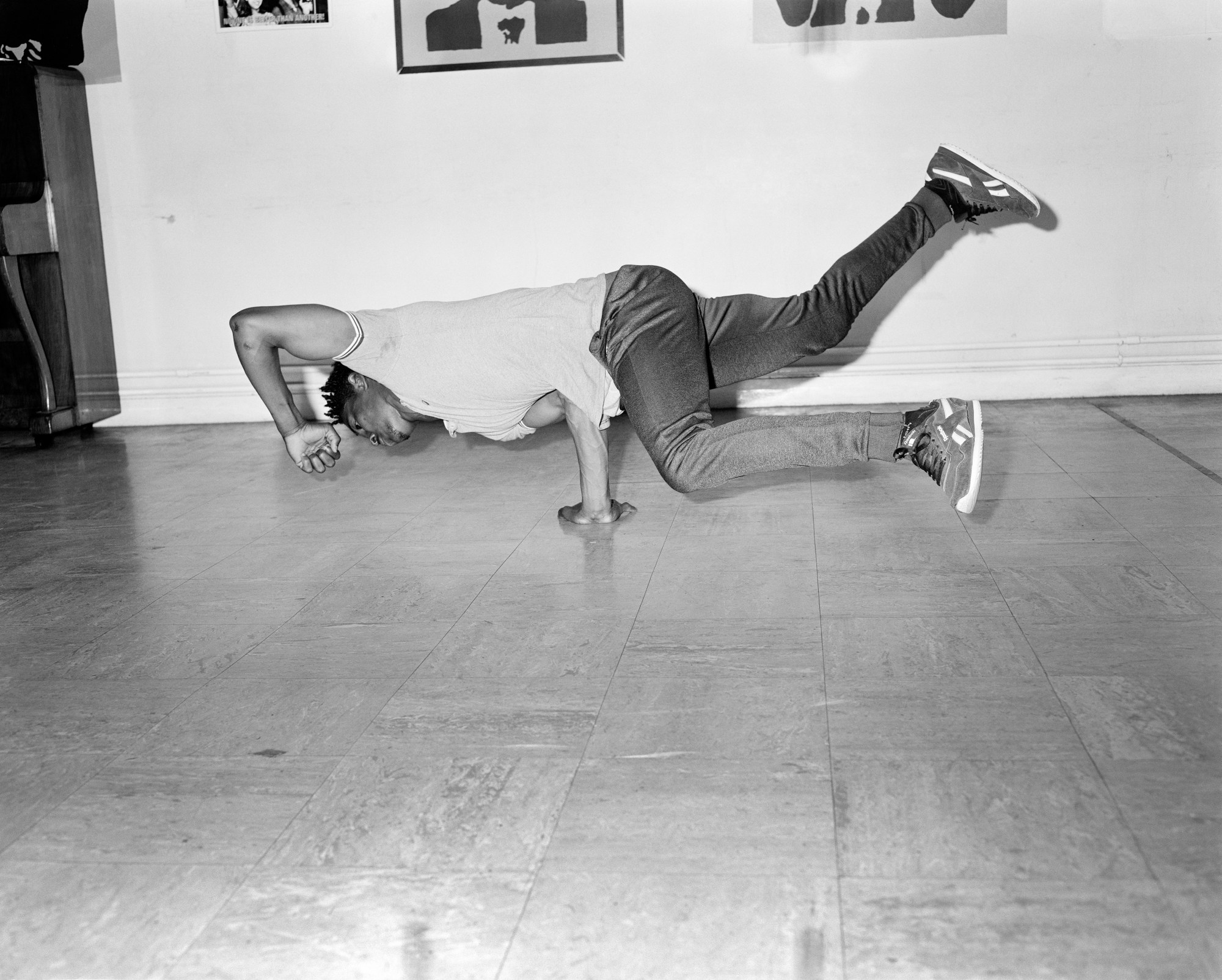

In stark contrast to the bold, saturated colour of Martin’s photographs, Olivia’s understated black and white portraits offer a poignant look at the city’s youth. She captured, among others, local rapper Chiedu Oraka, Miss Hull and District Agatha Lawton and Alphie Pearson, who at 12 years old is the UK’s youngest Elvis impersonator. Like Martin, Olivia was most struck by the enthusiasm that her project was met with by everyone she encountered.

“People are really tuned into what’s going on, particularly the kids I met,” she said. “I went to the Turner Prize exhibition last week and, although it was packed, I overheard a conversation between a visitor and one of the City of Culture volunteers. The visitor had obviously said something along the lines of not liking something in the show and the volunteer responded ‘well, that’s okay, that’s your opinion. You don’t have to like it, or even get it, but the important thing is that you’re engaging in a conversation about art, and that’s great’ — whatever happens in December when the programme comes to an end, I think people have really embraced what’s been going on.”

As well as being an amazing year for art, music-related events have proved a particular highlight too. Curated by John Grant, the Nordic-inspired North Atlantic Flux festival saw acts including Ghostigital and Actress descend on the city, while The Flaming Lips, Primal Scream, The Stranglers and Happy Mondays have all graced stages in unusual and intimate settings. A somewhat forgotten resident of the city with strong links to the music industry was recently celebrated too; curated by artist (and former i-D art director) Scott King, Trevor Key’s Top 40 shone the spotlight on the little-known photographer’s work during his time at Factory Records, when he created iconic covers for New Order alongside Peter Saville and, perhaps most famously, the artwork for Mike Oldfield’s seminal Tubular Bells.

“When I heard Hull was to be the City of Culture, my first thought was ‘Trevor needs to be included in this,'” said Scott. “I studied graphic design in Hull in the late 80s, and that’s when I first put a name to this amazing work that Trevor had done for New Order. There was an exhibition of D&AD winners on in Hull’s School of Art & Design in 1989, and on the staircase, wonkily stuck on the wall, was a copy of the band’s Technique. I remember marvelling at it, how chic it was, how it didn’t have any words or visible design on the cover. For me personally, I felt it important that the city celebrate Trevor, but on a broader scale, I thought back to that moment and if anything comes of this (and the year of culture in general), I hope the young people of Hull that might be contemplating studying art or design or something creative — that are maybe nervous of throwing themselves in — will see Trevor’s work as encouragement, and just go for it.”

The final exhibition in the city’s 365-day-long calendar of events is light installation Where Do We Go From Here? which asks the question that’s on everybody’s lips: is this the end? The answer is a firm and resounding “No.”

Not only will the city hold on to its title until 2020, but Hull’s Culture Company will build on the success of 2017 by transforming into a national arts organisation with a 20-year plan designed to put culture at the heart of the development of young people there. As director Martin Green says, “Culture is not an add-on, or simply ‘nice to have.’ This incredible year is already showing the potential of culture to transform lives, and our ambition is to build upon the positive impact the last year has had on Hull.” Or, as a local taxi driver recently put it in a slightly more candid statement, “It’s made the people of Hull like Hull again”. If the residents are convinced, perhaps it’s time the rest of the country followed suit too.