Robert Mapplethorpe was a visionary artist who, over his career, took photography into completely unchartered territory. From the moment he picked up his first camera in the 70s, Mapplethorpe’s dedication to capturing the perfect image never wavered. Whether taking self portraits, photographs of his muses, inanimate objects like flowers, his friends in the BDSM community or his later stylised nudes, Mapplethorpe applied the same meticulous approach to the image. He saw the beauty in everything. More broadly, Mapplethorpe used photography, quite consciously, to shift the way we habitually see things.

Importantly also, Robert Mapplethorpe’s work very openly explored queer culture and fetish as well as the fluidity of gender, sexuality and identity, which unmistakably helped pave the way for more open dialogue today.

With the opening of the new exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW, Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium, we asked the show’s co-ordinating curator, Isobel Parker Philip, to elaborate on the artist’s life, work and legacy.

i-D: Congratulations on the exhibition. What can we expect to see?

Isobel Parker Philip: It’s a comprehensive survey of more than 200 works, which trace the trajectory of his aesthetic and thematic preoccupations from his early experimentation with assemblage sculpture and collage, through to his initial engagement with photography via a Polaroid camera, and the progressive refinement of his pictorial vocabulary as he began to master the medium.

I understand Robert was given his first camera by his friend and neighbour at the Chelsea Hotel. Does this suggest he began taking photographs quite incidentally?

When he first started producing art, Mapplethorpe was largely disinterested in the photographic medium as a means of production. He was, however, using found images from magazines and periodicals as source material for his collages. As he continued to develop his practice he became increasingly frustrated with the images he was appropriating and decided to take up the camera to have greater control over pictorial content. Very quickly, he became attuned to the expressive possibilities of the medium. Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids betray signs of the stylistic temperament that would come to define his later studio portraits and figure studies. It is possible to discern his masterful command of the interplay of light and shadow and a sensitivity to tightly framed compositions in these early works.

Mapplethorpe is well known for his X, Y, Z portfolio of S&M images, floral still lives and nudes respectively. Does this work appear in the exhibition?

The X, Y and Z portfolios present a distillation of the three subjects that preoccupied Mapplethorpe in the early part of his career and in the exhibition, the 13 photographs in each portfolio appear on the wall as a full suite. It was, in part, Mapplethorpe’s intention for the portfolios to be seen en masse and in this configuration, it is possible to discern his broader artistic vision and agenda. Mapplethorpe wanted to draw these seemingly incongruent and incompatible subjects into dialogue and alert us to the state of formal equivalence that exists between a figure, a fetish and a flower.

Would you say that over his career he helped legitimise photography as a serious art form?

Mapplethorpe never doubted photography’s status as fine art and actively endorsed its acceptance as such within the art world at large. Subverting our expectations about the medium and how it transcribes reality, Mapplethorpe used photography to study and dramatise form. None of Mapplethorpe’s photographs are snapshots. No element of the scene is candid or incidental; everything has been staged for the camera.

When these works were shown in America in the 90s, just after his death in 1989, they became the subject of debate around freedom of speech, obscenity and funding for the arts. Would you say these images are really crucial in terms of their influence?

The exhibition is attentive to the political and historical significance of Mapplethorpe’s work and the conversations it has triggered over the years – conversations that remain relevant and critical today. Mapplethorpe’s work has often been co-opted within political arguments – including those launched by the Christian right wing to (in part) incite fear during the AIDS crisis and the debates about censorship that fuelled the culture wars – but this exhibition also affords us an opportunity to reacquaint ourselves with the enduring power of the photographs themselves with a degree of temporal distance.

He was really instrumental in bringing important issues to the foreground, important conversations we’re still having today.

By celebrating his own sexual identity and memorialising an increasingly visible community of gay men, Mapplethorpe afforded greater visibility to queer narratives. His work paved the way for subsequent generations of photographers and artists who continue to push the limits of representation and celebrate and explore their own identity. His works are as inspirational and challenging today as they were in the 70s and 80s when they were first displayed.

Did he see himself as an activist?

Not explicitly, no. Mapplethorpe never directly or strategically identified as a gay rights activist. Yet, to be openly gay at that time – in a post stonewall context and in the early days of the gay liberation movement – was an overtly political act. By inserting his own personal narrative into his work he was a catalyst for change.

Mapplethorpe also acknowledged that he used photography as a way to truly understand himself.

Mapplethorpe was attentive to the nuanced ways that identity could be captured (and crafted) by the camera. He didn’t see his life and his art as separate entities and all of his work is characterised by the foregrounding of his personal life. In Mapplethorpe’s work, the private became public. In fact his entire artistic output can be seen as an extended self-portrait. He was disclosing, celebrating and exploring his own identity as well as chronicling his immediate environment and the culture of his time. In all that he photographed, he’s forcing us to look at the world through his eyes.

Was he also using his photography to explore and question preconceived notions of gender?

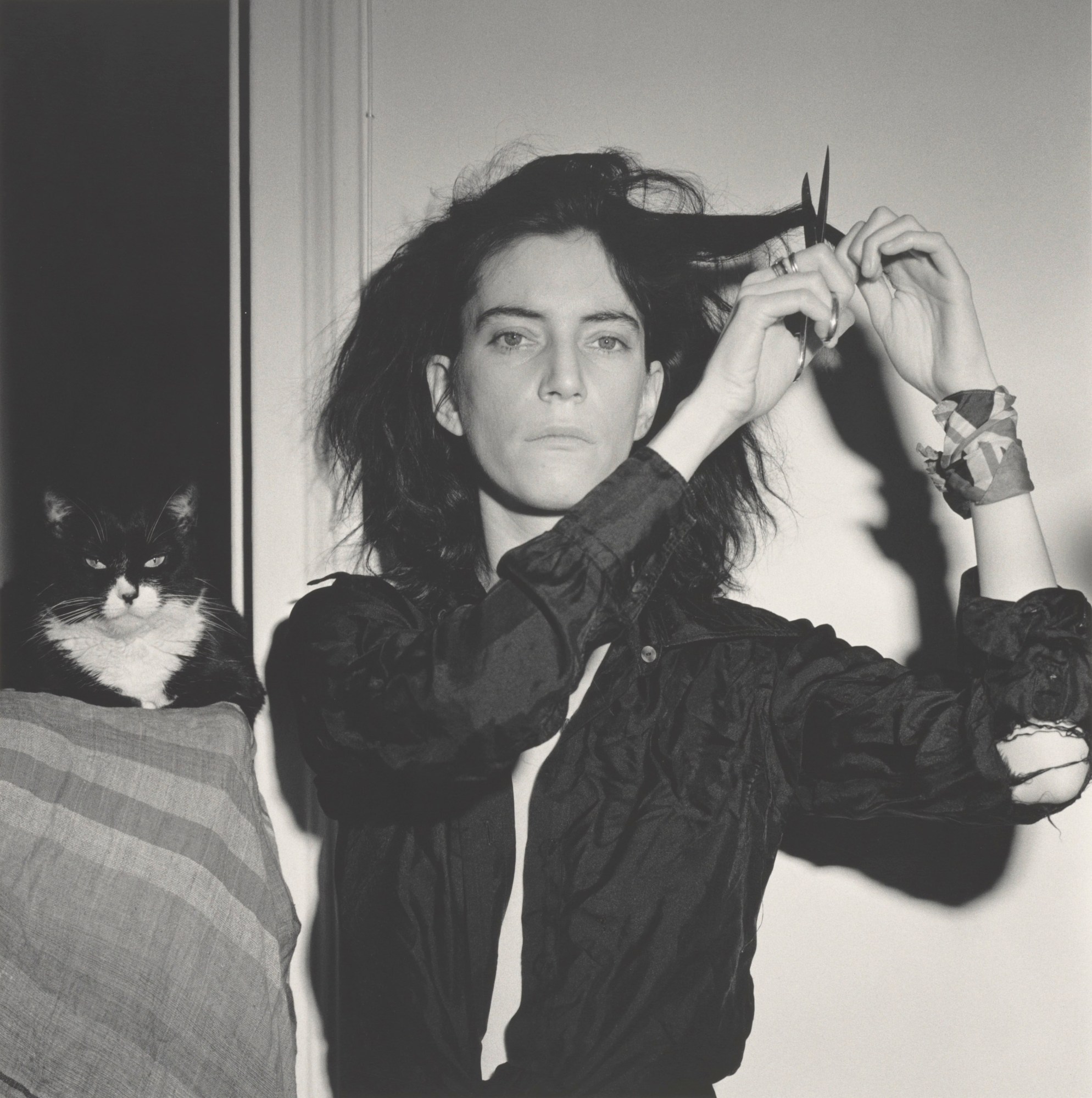

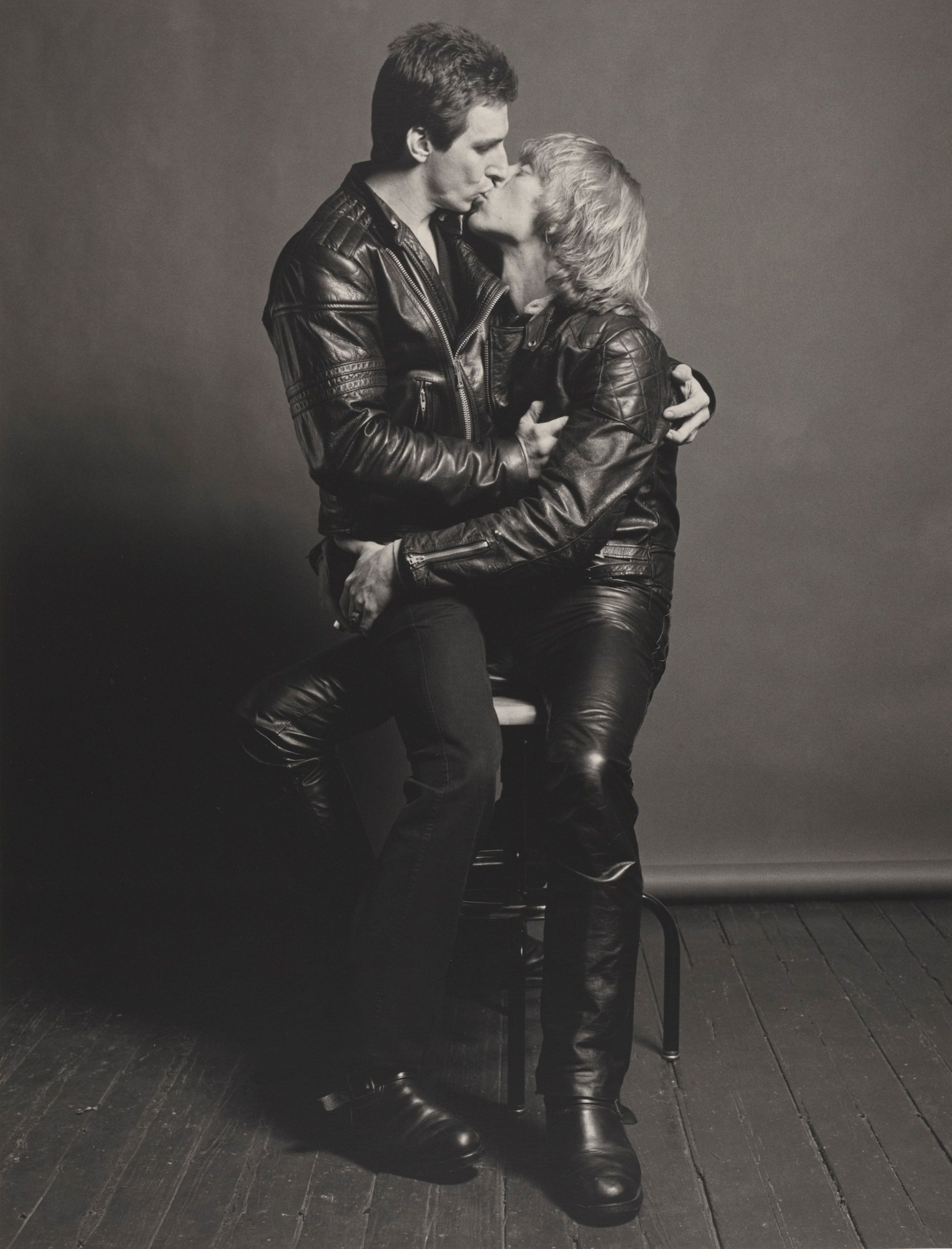

In many of his portraits, including those of himself, Mapplethorpe playfully subverted gender stereotypes. In some he adopts a hyper-masculine persona while in others he wears makeup and appears quite effeminate. His interest in the fluidity of gender also infiltrated his portraits of two important muses, Patti Smith and Lisa Lyon – both of whom have a section devoted to them in the exhibition. Mapplethorpe often amplified Smith’s androgynous appearance, most notably in the iconic photograph that adorned the cover of her debut album Horses, and in Lyon he found another cipher through which he could confuse and subvert gender. Lyon was a female body builder yet she saw herself as more of a performance artist whose body was her medium. Her working relationship with Mapplethorpe was collaborative, and for 6 years the two produced highly choreographed photographs where Lyon’s muscular physique was alternately amplified or offset by costumes and staging.

He used clothing in such interesting ways but more often than not, the body was the focus.

Mapplethorpe’s photographs of Lyon reveal an innate understanding of the language and communicative potential of fashion. Here, more than any other body of work he produced, he uses clothing and costuming as a dramatic and expressive conceit. But these works also showcase his prevailing interest in the body as a malleable and pliable form. In her different guises, Lyon was a chameleon-like subject. In his later figure studies, Mapplethorpe continues to explore the body’s malleability. Here, the body becomes a conduit for a study of form. It’s quite sculptural – as if he’s using the photographic medium to sculpt with light. No matter what the subject, Mapplethorpe pursued what he called ‘perfection in form’ and cultivated his own mode of classicism. In these later figure studies, where the body becomes an aesthetic ideal, this pursuit of formal perfection becomes more emphatic.

Finally, does the show include the haunting self-portraits he took towards the very end of his life?

The show ends as it begins, with a trio of self-portraits. Included in this final section of self-portraits – a section that operates as a punctuation point to the exhibition itself – is one of his most poignant artistic and personal statements. Taken in 1988, a year before he died of AIDS related conditions, the photograph of Mapplethorpe wearing a black turtleneck and holding a skull-topped cane is haunting and prophetically tragic. Against the black studio backdrop, all that is legible is Mapplethorpe’s face and hand holding the cane. He stares at us with that characteristically defiant stare but his face exposes his fragility. What’s in focus in this image is the hand and the skull; his face, by contrast, is slightly out of focus, as if it were on the edge of dissolution. This work survives as a fitting tribute to an artist whose practice was defined by the disclosure, and foregrounding, of his personal life.

‘Robert Mapplethorpe: the perfect medium’, a must see survey of his work, is on now at the Art Gallery of NSW until March 4th.

Credits

Text Briony Wright

Photographs Robert Mapplethorpe