New Jersey pop artist KAWS has been part of the i-D family since first introduced to photographer Matt Jones by Gimme 5’s director Michael Koppelman way back in ’97. In the 20 years since, KAWS (real name Brian Donnelly), has gone from tagging freight trains and subvertising billboards in Manhattan, to designing toys, clothing and 3D figures the size of buildings — marrying art and commerce without ever once compromising his vision. In 2008, i-D founder Terry Jones came up with the idea of a hook-up that would see KAWS illustrate the entirety of July’s The Stepping Stone Issue. “The crossover seemed really exciting, I just had to make sure we could work together before he was too busy with an exhibition,” said Terry at the time. “It’s a total entity, from cover to cover and much respect to the lucky collectors who manage to find the limited KAWS cover.” A decade on – and with those covers rarer than a can of dandelion and burdock – the pair sit down to chat Frieze, comics and planting a seed for the future.

TJ: I don’t know how many times we’ve talked over the years but the progress, I think, is incredible. Could you tell me about some of the new work you are putting out?

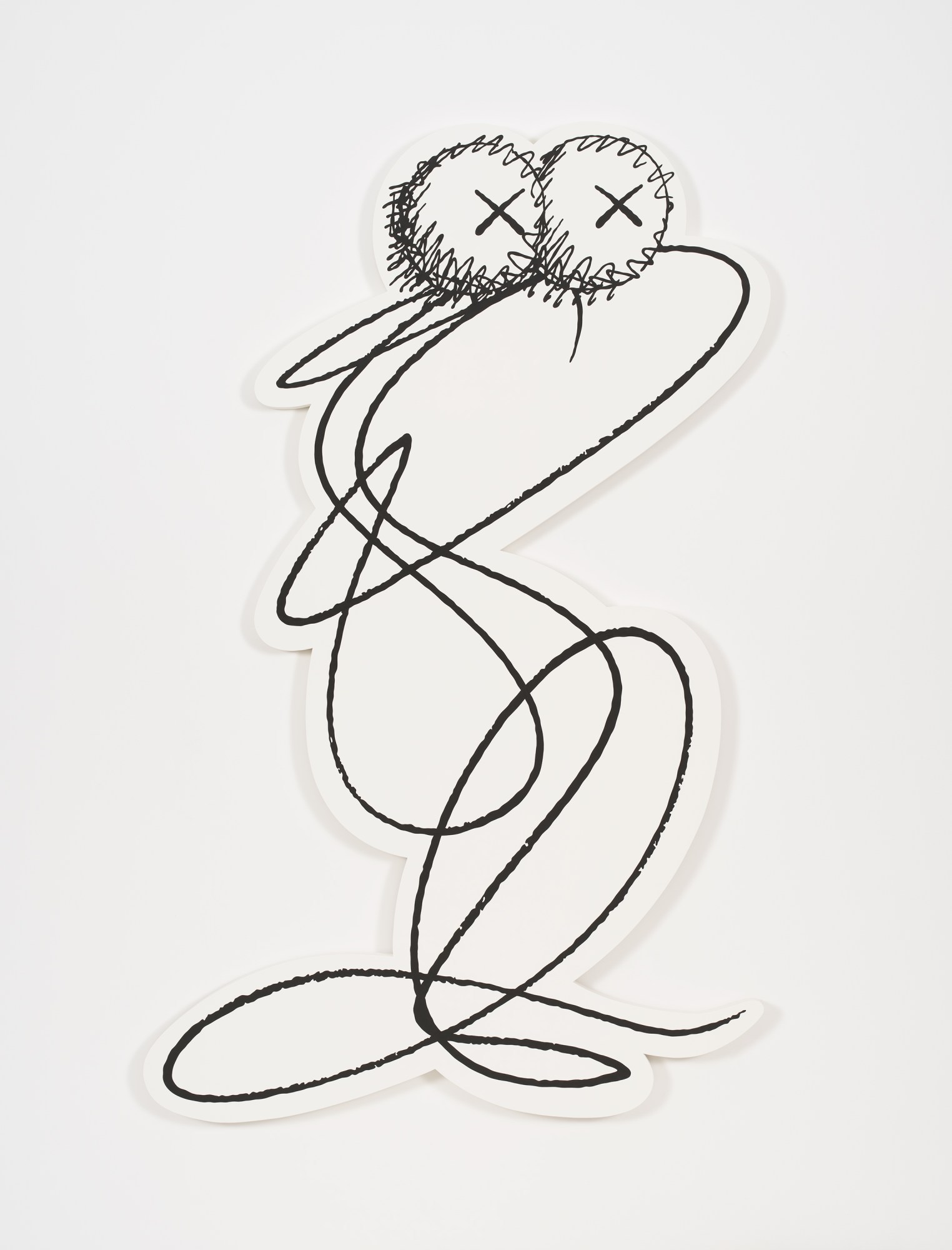

K: I’d just finished this show at the Fort Worth Modern, that was a sort of 20 year survey. And I came back and started doing these little, small tablet paintings that were really full-on in colour and composition. Really just experimental paintings. I started to try and really find my way around the imagery and that grew into the larger pieces that are now at Frieze. While that was happening, I got into doing these black and white paintings that are more like scribbles. And they’re maybe the first paintings in a while that aren’t taken from a source image or popular imagery. They consist of me doing little drawings and then turning them into these 10ft, 8ft paintings. They resemble stressful kind of characters, I feel. Almost portraits of people.

Did you have people in mind when you were doing them?

Less people in mind, more the general climate. How we’re feeling at the moment. It’s been a tense year. And I feel like the paintings are like these little stress balls.

The eyes are always important, aren’t they?

Yeah. It just keeps making its way into the work. I don’t feel like we’re done with it. I don’t want to push it out, just to not have it, you know? It feels like that brings it into the family somehow.

Can you tell us about Accomplice, one of your early works?

That was one of my earlier sculptures. At the time, the only ones I’d done were Chum, which was based on Michelin, and Companion, which is probably my most popular figure. I remember at the time, when I was making these things, everyone was saying, ‘Oh, street art!’ Putting an urban context to the work. I just thought, I’m going to create a character that has zero street cred, that’s as soft and friendly as can be, and just sort of shed some of those fans, some of that interest. That’s how Accomplice was made.

That idea of a companion or a chum, that’s going right back to really early work.

Yeah, that came from painting over the ads, when I sort of made the transition to a graffiti which was more into imagery than lettering. That’s when skull and crossbones and ‘X’s over the eyes sort of come into the work. It was just me becoming more interested in reaching a wider audience and looking at advertising as a parallel to graffiti. Like, how can I maximise visibility?

And now you’ve become a brand yourself.

I guess! It’s weird. I meet people and they talk about me as “that” or “your team” and I still think of myself as an individual, sending working out into the world from my studio. I realise that it’s grown but… I dunno. I’m not saying it hasn’t become a brand, but I definitely don’t feel like one. I feel like a person. I don’t feel any different to any of the other artists that I’ve followed.

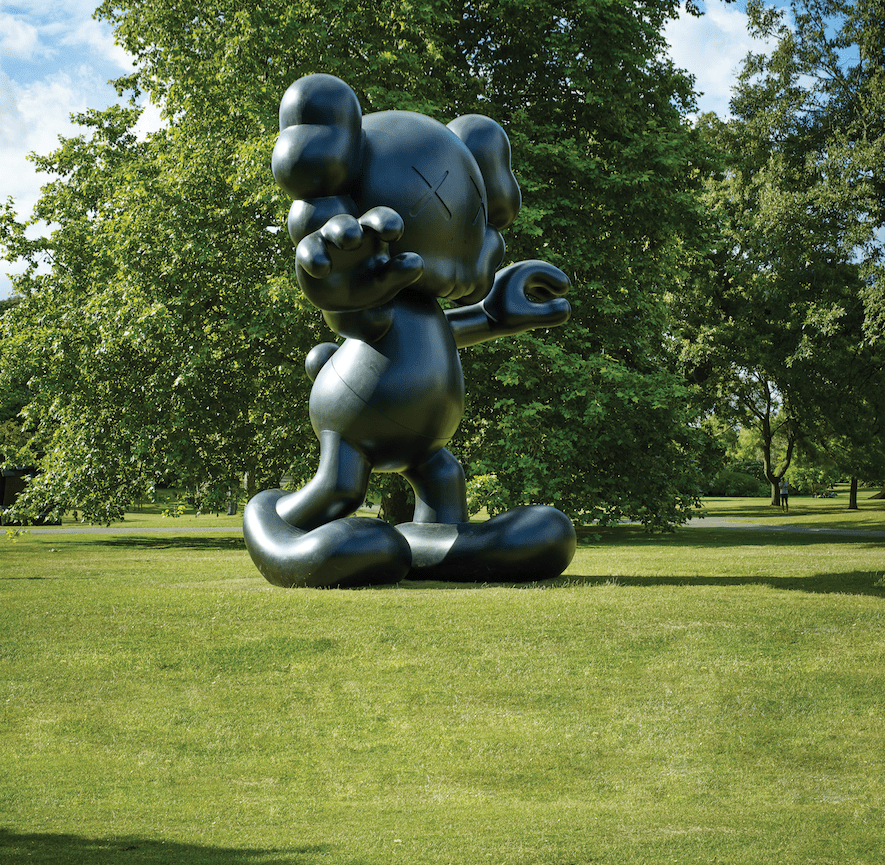

I think the thing that was interesting about your work was the idea of appropriation. You’d take the base of an advert and then create artwork from it. The piece in Regent’s Park are in such a huge public space — do you ever think that they might be worked on by someone else too? Your intention to use wood, for instance — had you had it in mind that it could be added to? In the same way that you scratch your mark on a tree, perhaps?

No, that wasn’t really my thought process with that. When I was making wood pieces it was because originally I started making small works and it brought me back to the idea of having wooden toys when you’re a kid. This intimate, vulnerable material that was such a different feeling to fiberglass. I feel like it has a real warmth to the work.

But it’s huge scale.

Yeah, exactly. So you have a thing where sometimes you make a sculpture but you still feel for it. It needs to be protected. I think it’s an interesting thing. Normally, when you’re faced with something that scale you feel dominated. But I think that makes you kind of wonder, is it going to be okay?

When you look back at your 20 year survey at Fort Worth, were there things where you thought, ‘Oh, I should have developed that more?’

Definitely. Graffiti itself is very repetitive, you’re painting the same letters. It’s even in the same form a lot of the time, you’re just hitting different freight trains or whatever. And when I started painting the phone booths, my sort of source images were very simple. It was really the photo I painted over that really changed it most times. But then I started to feel a pressure to move on and I wish I didn’t. I honestly wish I didn’t. I wish I did more of those works.

Because the booths aren’t there anymore.

Exactly. You don’t think about that. At the time, I left so much work on the street. And I felt like I did a lot but, looking back, I feel like I could do more.

Did you do any in London?

I think you know the answer to that! You might even have been an accomplice of that to some degree.

But they ripped them all out!

Yeah. There weren’t any that lasted in London. I’ve never seen any turn back up in market.

They didn’t place any value on it.

No, at the time, they didn’t. Some of them get saved but other ones just get destroyed.

Your first freight train that you put KAWS massively on. Whatever happened to that?

I mean, that wasn’t my first train. I’d been painting tonnes of trains at that point. But that actually still runs around. I’ve gotten, as recently as last year, an updated photo of it. That’s the great thing about social media now. Things pop up and you get to say, oh, that still exists.

Did you ever imagine graffiti would reach the point it is now? Having buildings that are carefully graffitied around the whole of Williamsburg? The evolution of something that started on the street and was initially thought of as vandalism…

It’s amazing. My first time out the country was to Germany and there was this guy who got me involved in an exhibition, but it was funded by the government. That just blew my mind. If I look back now, there’s always been strong support from Europe for the earlier graffiti shows in the 80s. But I don’t think I would have imagined it growing to the scale it is.

You never did paper works did you?

Hardly. Honestly, as street art started getting really embraced, I started getting more and more suspicious of it. When I was doing it in the 90s it was great. It felt like this sort of fresh thing that no one knew what to do with, and that was part of why I was interested in it. And then as blogs and stuff started popping up dedicated to street art and there was a point when everyone was a street artist, I just got less and less interested. My interests and directions had changed.

Back with the Frieze exhibition, what would you like to come out of that?

I mean Frieze, for me, was sort of a fun exercise to show new paintings. London is a place that I feel like I have a long relationship with, but I don’t have a relationship any galleries or have any institutional shows there. You know, working with [art dealer] Emmanuel Perrotin and putting the works in his booth was just an opportunity to get original painting in front of people to see. Not see online, not see in print. It was a really simple goal.

Were they specially done for the space?

Yeah, it’s kind of what I’ve been working on this year. I did consider the space and how they would hang.

So if you wanted to bring a piece of work back home to New Jersey…

You know it’s funny. I was approached by the mayor of Jersey and we were discussing it, but at the moment nothing has solidified.

Would there be a favourite spot? A road or a square or a park?

I think Journal Square, that area where the train station is. I think I put in more hours there as a kid than any other area of Jersey City. My grandfather used to work for the train company and when I was little he used to take me on the train to Newark or Manhattan. He’d take me for little rides, get out, walk a bit and then get back on the train. Later his sons, my uncles, used to take me to Manhattan to go to Forbidden Planet, the comic store. I’d be on the train almost everyday going into the city because it was so easy.

Do you have favourite comics?

Not really… When I think of comics as an adult, I think of the underground artists, whether it’s S. Clay Wilson or Robert Crumb. When I was younger, I wasn’t the kid that read a lot of comics.

Did you meet Crumb ever?

Yeah, I couple of times. It’s so funny because with the type of work that I make I put myself into this world where I have these massive objects and there’s storage and you need a studio and all this stuff, and I always fantasize about how [with comics] this whole world exists in something no bigger than a page. And it still has such a presence and an impact on the world. I think that’s what I really love about the work.

And Barry McGee?

Yeah, when I first met Barry he was doing all these amazing works. Growing up in the graffiti world, you get to meet all these different people through the work you make. And when I thought of galleries, I thought of the ’80s graffitti artists who kind of got sucked into stardom and spat out. That was a moment that came and went. And in the ’90s, Barry was the first artist to really elbow out new ground for an artist coming from a street background. Even as a younger artist I went to stay with him in San Francisco in ’96, ’97, and did a bunch of work. To see somebody kind of pushing it and opening new doors planted a seed, I feel, for myself.

And if you wanted to plant any new seeds for the future?

I wouldn’t know how to tell you how. Hopefully the stuff that I put out into the world gets the next person to think about how they can do it better and do it their way.

Frieze Sculpture is open until 8 October