Asking someone about their first time in a gay bar should be like asking them about losing their virginity – a landmark that they’re meant to remember forever. Well, I don’t remember my first time in a gay bar. Maybe because there have been so many. I know it was in 2009, when options seemed limited to naff Soho gay bars with pink or purple interiors. There was the lesbian haunt Candy Bar, a tacky and male-heavy club Escape round the corner, Ku Bar, Madame Jojo’s, G-A-Y. I was just about too young to witness the glamour of Trailer Trash or Boom Box, but when I tired of Soho I found East London gay pubs The Joiners Arms and The George and Dragon waiting, both uninhibited spaces you could rely on any day of the week. Eventually, I moved on from those too. For a while, I even got tired of gay bars altogether.

Just as our personal relationships with going clubbing ebb and flow, so do the clubs on offer to us. Almost all of the clubs and bars I mentioned above have disappeared now, vanishing in a particularly brutal spike of closures to hit London’s queer scene over the last 10 years. Anyone who went to these places will have felt it first-hand, but now the statistics can affirm what we already know to be true: between 2006 and 2016, more than half of London’s LGBT venues closed. According to the report that has charted the closures, the majority of queer spaces closed for reasons to do with gentrification, meaning bars were bought out by luxury property developers, couldn’t afford rent hikes, or else closed down after incidents that might have threatened the shiny new facade of the area in which they dwelt. Over 10 years, 125 LGBT venues became just 53, and the spate of closures became known as a crisis.

While gentrification was the main reason for the closures, many people wondered if there was another one at play: the idea of assimilation, the idea that, if being LGBT no longer has to define you or your lifestyle as “different” or “alternative”, gay spaces might not be as necessary as they once were. As Sarah Schulman points out in her book The Gentrification of the Mind, gentrification doesn’t just happen to cities, but to people. It can be a way of thinking, one that champions the private over the public, the individual over the community, sameness over difference. 2014 was the year The Joiners shut, but it was also the year we got same-sex marriage and Barclay’s Bank became a sponsor of Pride. We were forced to ask ourselves whether we had let queer culture – and with it, our bars – finally be subsumed by the mainstream.

Privately, I asked what role I had to play in this assimilation narrative. In 2014 it had been five years since I started going out on the rapidly diminishing gay “scene” and I was going to gay bars less, maybe because I was older, I had a full time job, had a close set of LGBT friends, a girlfriend, and had dealt with a lot of the coming out issues that made me want to explore my identity in gay bars to begin with. I felt a sense of complicity; maybe I had selfishly taken what I needed from these spaces and then abandoned them in their time of need. Or as a queerer Carrie Bradshaw might put it: Was I going to gay bars less because there were less of them, or were there less of gay bars because I’d stopped going to them?

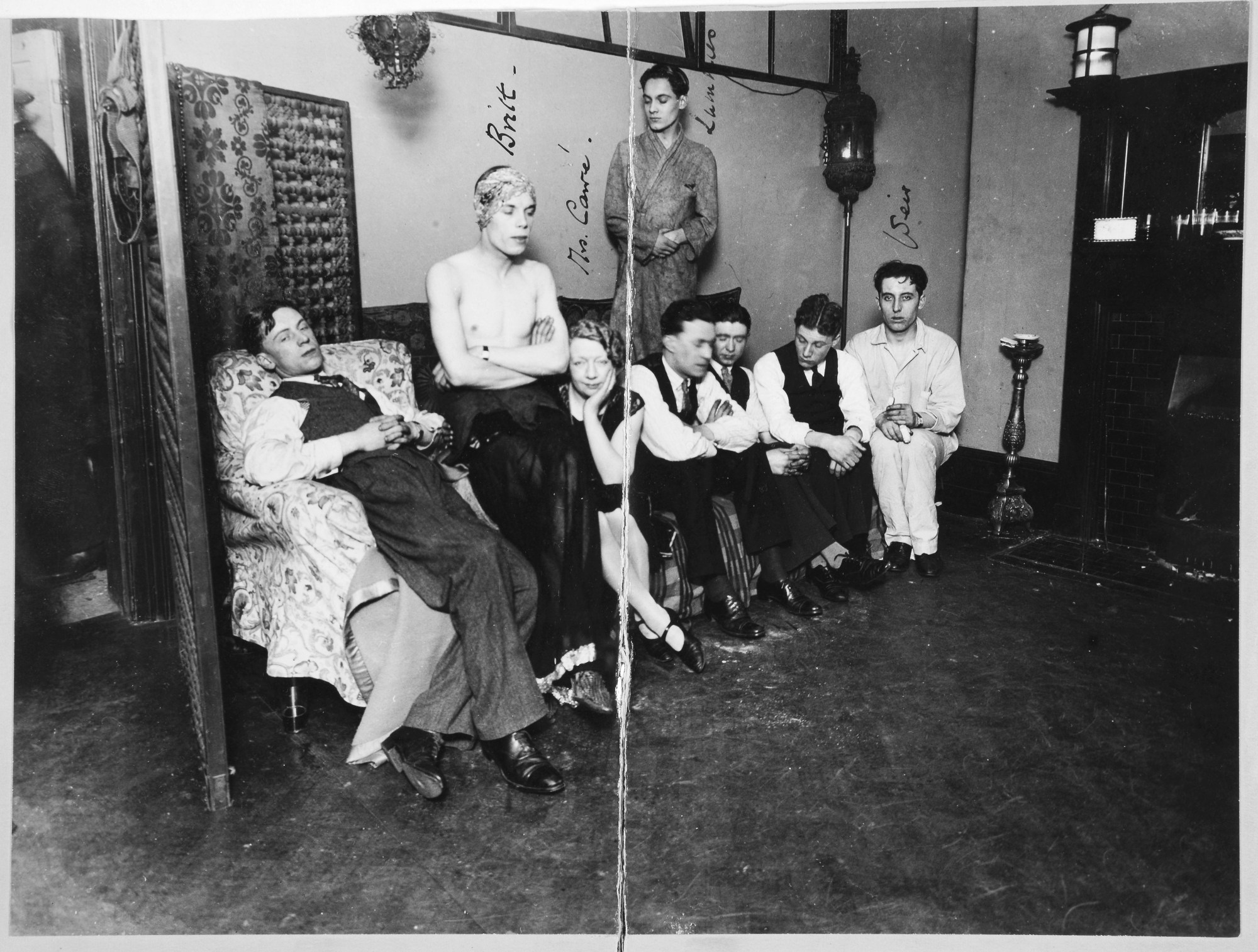

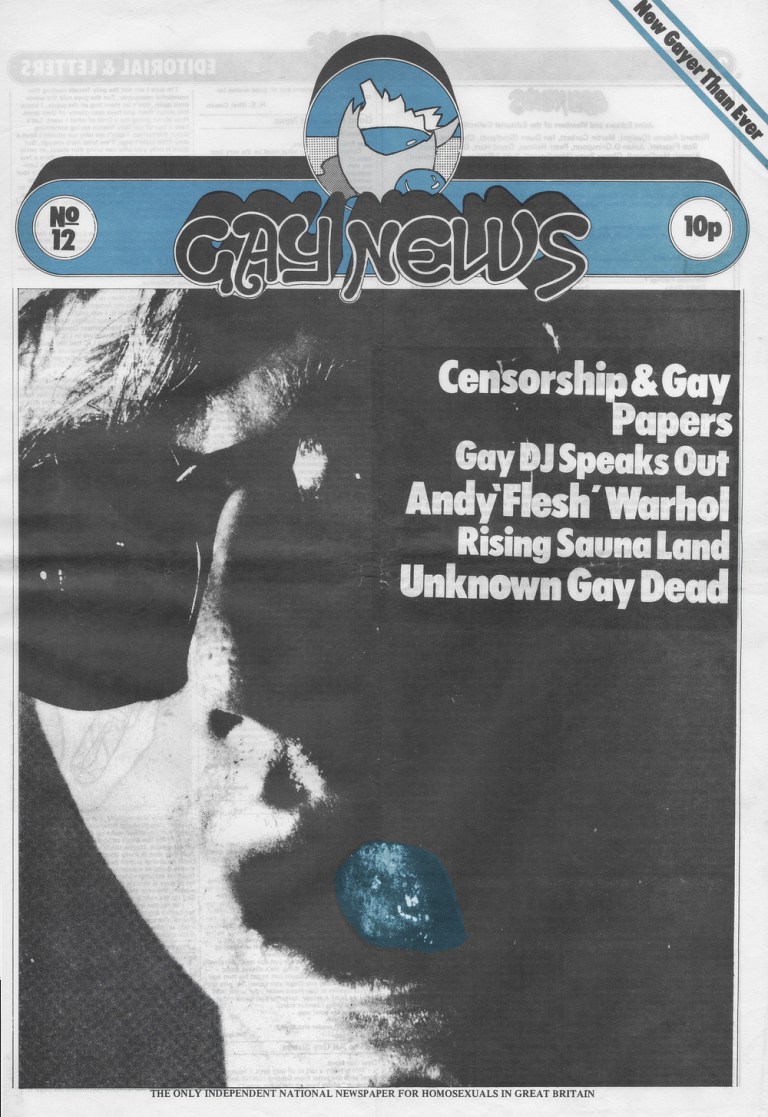

As distressing as it was to watch queer London vanish before our eyes – Soho’s sex shops evaporating, rainbow flags disappearing, and even that new “gaybourhood” Hackney losing its status as one – today, a few years on from the thick of the closures, the picture doesn’t look totally bad. Walking around a new exhibition that opened at the National Trust Property Sutton House last week, “Light After Dark”: a celebration of London’s queer club culture – I was reminded of the one thing that we can always rely on to stay the same about the city’s LGBT scene, and that’s its ability to reinvent itself. In commemorating some of the queer spaces that have been lost over the last 100 years, the photos and other ephemera in the exhibition are a testament to the fact that, no matter how many bars have been swallowed up by the annals of history, or how many club nights come have to an end, there’s always something else, always “Light After Dark”.

In December 2014, right after I heard The Joiners was closing, and having not gone out for a while, I got a glimpse of what could be created out of the rubble. It was an event run by South London-based artists Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings called “Is the Gay Bar a Grave?” Like most of their parties, it was held in a purpose built space in their Peckham studio that featured all the hallmarks of a classic gay bar, like a tacky aesthetic and chart pop music, only there was no door fee, drinks were super cheap and genderqueer and non-binary bodies were made to feel welcome. As Rosie told i-D a little later, it was about creating a safe and inclusive space for their friends that they didn’t feel existed anywhere else, “but to also try and re-materialise political issues [they] had been thinking about: assimilations, the way gay narratives get consigned to mainstream history, or just ignored.”

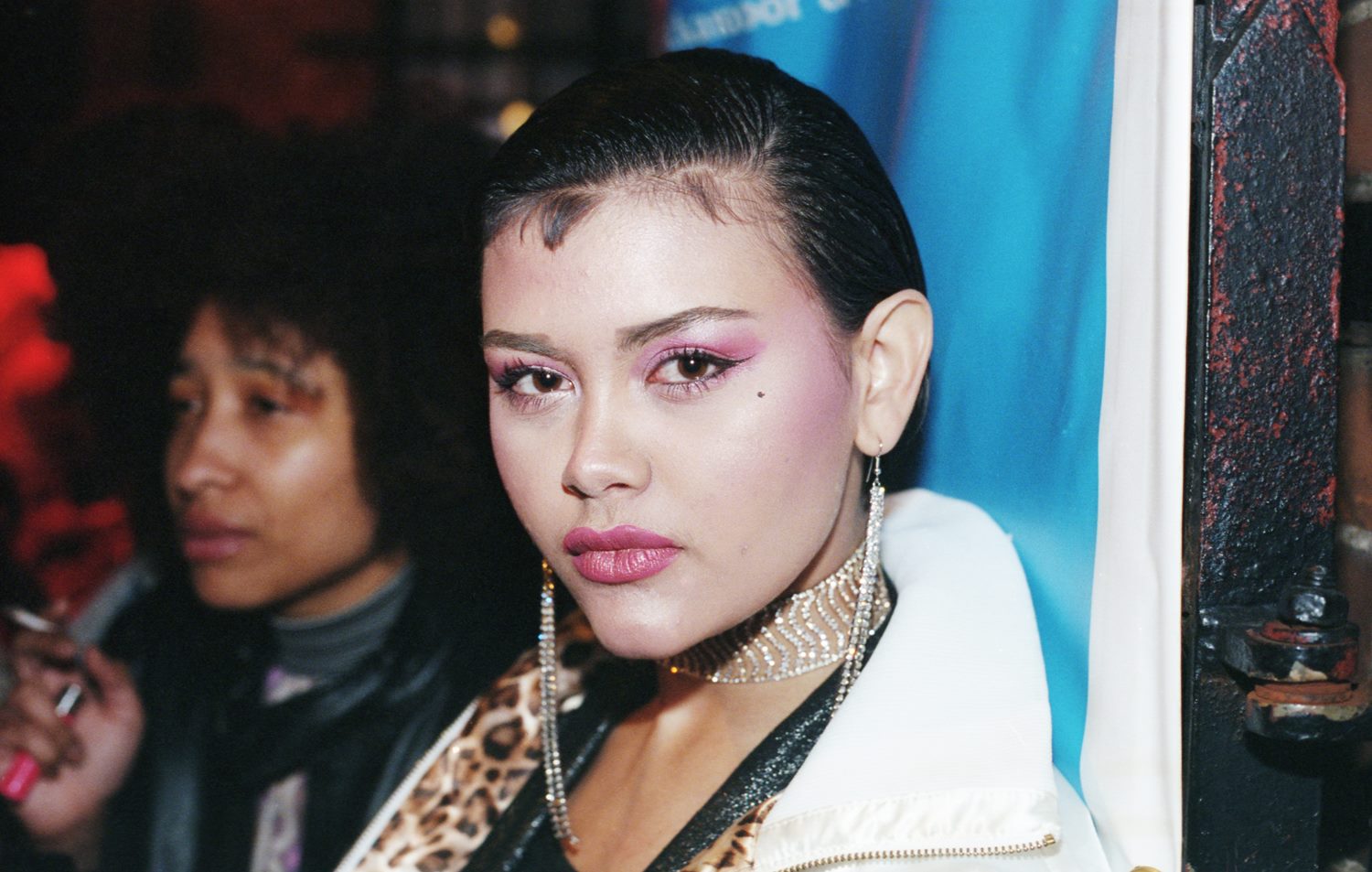

Their events turned out to be some of the best queer parties I’ve ever been to (although maybe that wasn’t hard); they felt safe, were inexpensive and diverse. Soon, other queer spaces began to spring up across the capital bearing similar hallmarks, like Kuntinuum, a salon for the of sharing work by creatives who self-identify as lesbian, bi and queer women, trans and non-binary. As a place for people to come together and watch films and converse, it didn’t centre itself around alcohol, but around the exchanging ideas together in an IRL space. Harley, who still runs Kuntinuum now, told me: “I feel like Kuntinuum has, by existing, questioned why these kinds of spaces are lacking.” The same could be said for BBZ; a night for queer femmes and non-binary people of colour, it started a year and a half ago in Busta Mantis, a Caribbean restaurant in Deptford, and sought to combine a party with a place for artists to show their work.

“Queer people of colour have always been in south London, it’s just that no one had paid attention to them for a while” Tia, one half of BBZ, told me recently, referencing nights for women of colour like Systematic at Brixton Women’s Centre in the 80s. “Apart from the closure of Candy Bar, another example of female queer identity being pushed out, I wasn’t really affected by closures of gay bars in London because they weren’t for me,” she added, emphasising that last bit. Tia explained that she and her partner Nadine started BBZ because they were frustrated at the fact you’d have to travel to east London to go to anything remotely queer and then, when you got there, it was mostly for gay men anyway. They also found that if it was the music they wanted to listen to, there was usually a lot of cultural appropriation going on. Like @Gaybar and Kuntinuum, BBZ wasn’t (and still isn’t) about filling a void that had been left by the closures of the pink and purple interiored bars of central London, but about creating a better vision of LGBT clubbing.

Look around today, and there’s good reason for people like me – and people who were even more disillusioned with LGBT clubbing – to go out again. At least occasionally. @gaybar isn’t running at the moment, but Kuntinuum is. Every once in a while there’s a weird queer party at Lima Zulu in Manor House; a giant queue to get into Pxssy Palace, a night centring trans and femme people of colour in Hackney Wick; there’s the Campervan, a queer performance space that can pop up anywhere in London, although usually it’s Peckham, and always turns into an outdoor dance party. And then there’s Chapter 10, a monthly queer warehouse party, also in Hackney Wick, that aims to take house music back to its queer origins in Detroit and Chicago.

Dalston Superstore owner Dan Beaumont started Chapter 10 with friends Morgan Clement and Charlie Porter when he looked at the London club scene and saw something “too homogenised, too mainstream.” He knew queer and non-binary dancers were willing to travel, so he started something further out, that was not for profit – a measure taken to keep things purist. If the owner of one of the few gay bars that actually survived London’s spate of closures has started a club night not in a gay bar, and not for profit, things really must have shifted. “People are definitely questioning the need for gay bars and figuring out new ways of doing things”, agreed Dan, when I put this to him. “I think as activism infiltrates pockets of gay culture like clubbing, commercial models are being disrupted. Horizontal, noncommercial groupings of people will only become more influential in gay nightlife. You can see that in the explosion of the illegal party scene in London – in Hackney Marshes, Tottenham, warehouses in south London – it’s definitely a response to the lack of legal venues. It’s a necessary step to be taken.”

Permanent LGBT spaces are necessary, we know this from the spike in LGBT hate crimes that took place in the UK last year, and from the fact that the UCL Urban Lab report on closures found the loss of London venues to be detrimental to LGBT people’s health. Plus, as Tia puts it, a permanent queer space by and for people of colour is the end goal for BBZ not just because the community needs it, but because it would get rid of a lot of their stress around finding venues each time they want to throw a party (something @gaybar and Kuntinuum have also reported experiencing). But perhaps it’s time to acknowledge that some pockets of LGBT nightlife of yesteryear might have succumbed to gentrified ways of thinking themselves, alienating queer people of colour, pushing out female or non-binary bodies, charging expensive door fees that queer people can’t afford.

If history tells us London’s queer nightlife will always move in cycles, I would argue that right now a renaissance of underground queer culture has materialised in defiance to the city’s closures, and it’s anything but the boring, sanctified or commercialised gay bar model that dominated 10 years ago. The cycle gives me hope that our LGBT spaces will return, but when they do, they should take a lesson from what’s replaced them: something queerer, more resistant.

Light After Dark runs at Sutton House in Hackney until Sunday 29th October 2017