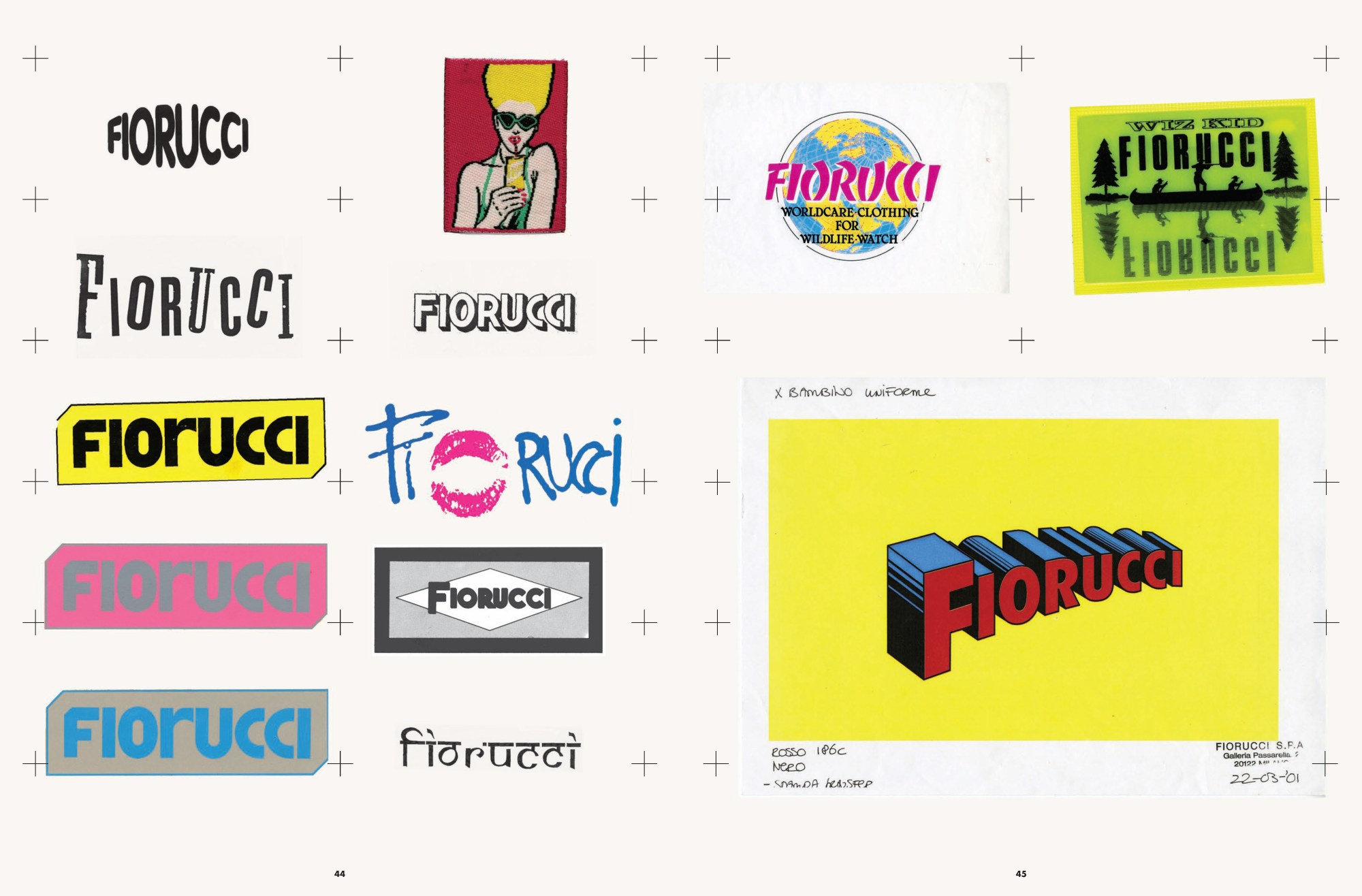

Fiorucci was the first fashion label that truly existed in print. There were clothes, of course, and there were products and people and parties — but always, always print. The company rarely took paid advertising. They didn’t need to. They made their own magazines. In London, the special relationship with i-D, which saw founder Terry Jones act as Fiorucci’s art director and Elio as the magazine’s principal sponsor, resulted in the production of special Fiorucci–only editions. In America, Fiorucci fanzines were self-published in Los Angeles and Chicago to carry news of the store openings. In New York, a special Fiorucci issue of NIGHT was issued. In Milan, Fiorucci produced one particularly remarkable publication, which was stapled completely closed on all sides as well as through the centre — making it impenetrable. The Italian text, roughly translated, read: “The cool thing to do would be to not look inside.” The archive example remains unopened.

David Owen: Can you take me right back to the start of your Fiorucci story?

Terry Jones: I was art directing British Vogue from 1972 to 1977. I had worked with Oliviero Toscani at Vanity Fair before that, which was the first time we had met. I had a struggle getting Oliviero accepted by the editors at British Vogue. Obviously he was working a lot in Italy with Flavio Lucchini at L’Uomo Vogue. We had this working relationship in which he would be antagonistic, whereas I was non-confrontational. I would try and rub off his edges, so that the results were always positive. When he was in London he would stay with Tricia and me at our house. He was going out with Donna Jordan at the time, and we all became friends. Then he invited us to stay with him at his house in Tuscany. One Easter we were there—Tricia and I and our daughter Kayt, who was just a baby—and Kayt had a fall from the first floor and fractured her skull. Oliviero was amazing and took over getting her into the local hospital. That relationship was kind of like total family. We made him honorary godfather to Kayt.

DO: And Oliviero introduced you to Fiorucci?

TJ: Another time when we were in Tuscany, Elio came and visited. I don’t speak Italian and he didn’t speak English — although I always suspected he understood everything. So we would just talk, in English and then in Italian, and have an understanding. He was like a guru priest, who would encourage ideas and be a conduit to meeting people. In 1977, I quit Vogue and went on to do several projects with Oliviero. I would be in Italy regularly and met Spago, the illustrator who was living in Oliviero’s flat. He would be my guide to the Milan scene, and that’s when I met up with Giannino Malossi of DXing. I would spend one week a month in Italy when I was working on Donna, and I would hang out with the Fiorucci crew in the evenings. After I had started i-D, we were struggling with distribution, and in 1983 Elio came on board as a global distributor. At the same time he asked if I would be Fiorucci’s creative director. So then he became a major client. Elio had come up with this project to do the Panini stickers. The finance was enough for me to invest in my first computer — the Apple IIe. It was also enough to bring on board people like Caryn Franklin, who was a student at Saint Martin’s at the time, and Robin Derrick and Stephen Male, because I needed someone who could draw. I would always find people with creative skills and direct them to do stuff. Moira Bogue was a student at the Royal College of Art, but she came to do her thesis on i-D and started working with us. We spent the days on Fiorucci and the nights on i-D. Fiorucci was important. That was a crucial year in terms of whether or not I was going to survive.

DO: And you must have enjoyed spending time in Italy?

TJ: It was fun going into the environment that Fiorucci had. Quite a different experience than I had ever had before. I had never taken formal lunches, but at Fiorucci in Milan everyone stopped and ate together. Then I would work late into the evening and Elio would drop me off at whatever hotel I’d booked into. It was almost like a nomadic way of working for me. I was the alien who didn’t speak Italian and always needed a translator. I was able to do whatever I wanted to do. Elio just said, “You know what I like, do whatever you want.” The graphic language was always upbeat and entertaining and something that had a powerful graphic impact. There was a history of that. Spago was a brilliant illustrator and Oliviero made really strong, graphic photography.

DO: And there was a real cross-pollination of ideas between i-D and Fiorucci?

TJ: The Panini sticker book was the big project for Fiorucci, and then catalogues and posters. I asked Nick Knight to do three posters. That was very early on in Nick’s career. I was inspired by James Bond titles — the starting point in a psychedelic mix. We did those and then one pure one with a girl who had just been on the cover. And then Mark Lebon was one of our contributors. We would produce a double page for Fiorucci for i-D and would have the budget to do it in a studio. I had been speaking with Madonna’s agent after she performed at a Fiorucci party in Paris — she just came down while we were doing the Fiorucci spread and no one knew who she was. She

was just a club girl. So she appeared in the Sade cover issue and then had her own cover the following issue. That spontaneity was great.

DO: I wonder how much Elio was drawing on London and the city’s street style through working with you and i-D?

TJ: My sensibility was always to look for the theatre of life. That was what punk brought to London—that theatre. I always loved the diversity of London and Elio picked up on that very early on. Kensington Market and the Kings Road were an inspiration for him. What was interesting was that he was already doing that through all his travels, but in London he just saw this amazing theatre on the street. He was already buying people like Bodymap and the young designers we had featured in i-D, but he wanted to produce his own line. So I suggested Vivienne Westwood, saying if he could get Vivienne on board that would be great. I set up a meeting in the upstairs restaurant of Dickins and Jones on Regent Street. There was this room, which was like an old ladies’ restaurant. I just thought this would be an incongruous place to have Elio Fiorucci and Vivienne Westwood together for lunch! And it was an extraordinary meeting. You had Elio in his blazer and jeans, but still very priestlike in his dress, and then Vivienne with her pink hair. And we were having this really important meeting surrounded by ladies with grey hair dyes. The vision was perfect for me. That meeting led to their collaboration for World School, which was a fantastic collection. A denim collection that was way ahead of its time. Technically it was brilliant. She had the talent to produce a fabric. She did that collection and Simon Foxton did a menswear sport collection, and both were ahead of their time. It was too ahead of the buyers and they just didn’t get it. It would be relevant if you saw it today. The price point was higher and that freaked people out. It was great—really good—and never got off the ground.

DO: I didn’t know anything about that Westwood collection at all! It leads me to ask another question: how chaotic was it at Fiorucci?

TJ: I don’t think it was chaotic at all. Elio would drift in and out, but his spirit was there. Because he really didn’t say a lot. At least, not a lot to me—other than, “Do what you want to do.” But the people who were working there in production were really great. The financial partner or backer that he had in later years wasn’t great to deal with. That division between the financial and the creative became the big issue. But years before I worked with Elio, Oliviero had taken me to a Fiorucci dinner and there were six bankers or financiers and six creatives, including Nicola Guiducci, who ran Club Plastic in Milan. I was just sucking in the sound as it was going off in Italian. That schizophrenia—it was a typical Gemini personality of putting two cultures together. But that was a creative energy, rather than a chaotic energy.

Taken from Fiorucci by Rizzoli