Little unites suburban girls as powerfully as the shared urge to turn dreams into writing, to pin pictures up on bedroom walls. And sure, we grow up to regret our obsessive diary entries, and our blu-tacked shrines to rock stars, but the art of our girlhood proves that those inner worlds matter.

Jenny Watson has spent the last four decades making conceptual paintings that give the smallest rituals of girlhood the anti-establishment energy of a post-punk anthem. To stand in front of Watson’s pictures of Twiggy, of horses mid-gallop, of winged girls painted on burlap and pink cotton — on show as part of The Fabric of Fantasy, her new survey show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney — is to be reminded that our most private moments contain seeds of the epic. That we are — or could become — the itinerant heroines of our own lives.

“I had this idea that I could I filter this very ordinary perspective of a girl into this highfalutin conceptual art and in a way, that’s always been my experiment. And I dare say that it’s worked,” laughs Watson, who shares a property outside Brisbane with her horses. “When I let myself explore my ordinary suburban background, that really gave me license to do anything. There was a point in art history at which a girl would have felt that she couldn’t make a painting of her favourite movie character.” Jenny’s alter-ego, a red-haired girl based loosely on Alice in Wonderland, plays a starring role in her work.

“From animals, horses and birds to close friends and women in movies, I chose to paint whatever I want. This freedom was radical. At the time, conceptual art had a certain look. But the [focus on] female experience made my work look unique.”

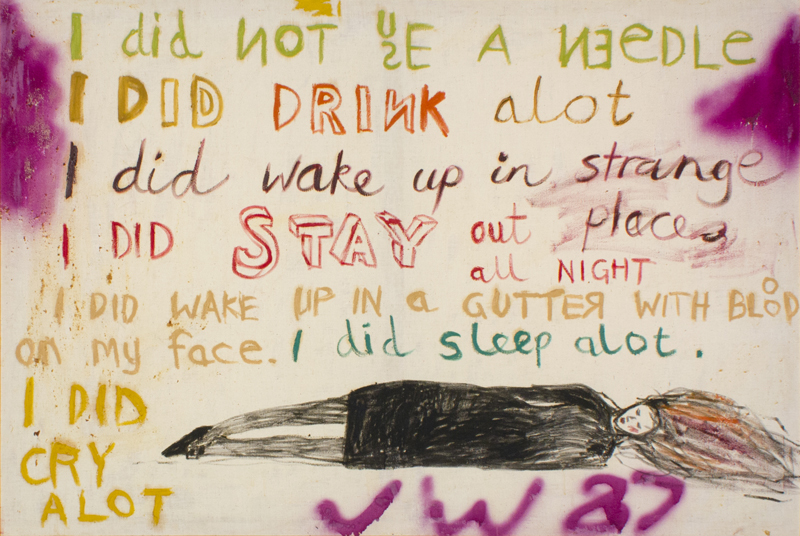

When you stroll through the MCA’s Level Three Galleries, home to over 100 of Watson’s paintings from the 1970s to the present, it’s impossible not to be struck by the force of her vision. It’s even harder to stay unmoved by the warmth and intimacy — rare in the world of conceptual art — of her voice. In one room, portraits of Nick Cave and The Go-Betweens, members of the Melbourne post-punk scene that the artist herself helped usher in, are as tender as a well-thumbed photograph. Another space is given over to works like I Dreamed I Was A Calvin Klein Ad (1995), a nod to a New York billboard painted on green taffeta, distilling the hopes of the young female artist trying to make it in that hulking big city. My favourite: a series of girls wielding martini glasses and holding telephones accompanied by panels of stream-of-consciousness text. Some quips are deadpan digs at the art world (“This painting is in the process of being purchased by a museum”), others (“She would choose her clothes, usually black, and lay them on her bed.”) riffs on her life. “I love the look of text, the feel of text, the sense that it could be a diary entry, a shopping list, a cry of help,” Watson muses. “When we look at a foreign language that we can’t read, we realise how abstract language is. It’s just shapes and forms. I just love the way it looks in paint.”

Watson grew up in Mont Albert and the Dandenongs, the outskirts of Melbourne. “My school-friend’s father was an oil painter and I went to his evening classes. Being out at night, in a studio, talking about art with the smell of turpentine — I found it so exciting and developed skills early on,” she says, adding that she later enrolled in the National Gallery School, under the dean Lenton Parr. In 1974, the American feminist art critic Lucy Lippard visited Australia and Watson was tasked with showing her around the studios of women artists. A few years later, punk hit Melbourne. For Watson, whose first exhibition was with the Chapman Powell Street Gallery in 1973, these cultural moments were connected. They also sealed her path.

“[Lucy Lippard] found that a lot of Australian women artists were working really seriously but were not that visible so the painter, Lesley Dumbrell started the Women’s Art Register in Melbourne to lobby galleries to put more women artists in their collections, include them in group shows and hire more female teachers in art schools,” she recalls, eyes twinkling.

“A lot of things changed for the better around that time! And then in 1977, music exploded. I’d been in London but came back because there was so much happening at the time in Melbourne. There were clubs like the Tiger Lounge and Crystal Ballroom. It was about two dollars to get in and we drank beer not wine. Everyone knew each other. It was a very small scene.” Even now, Watson’s best paintings are wild, throbbing with a rhythm that’s greater than the sum of paint or wordplay or rabbit glue.

It comes as no surprise to learn that Jenny wasn’t content to stay in St Kilda, or make art that simply documented that time and place. At 39, she held her first international exhibition in Frankfurt, and was soon after championed by Annina Nosei, the New York dealer who’s credited with discovering Basquiat.

“Annina Nosei and I did six shows between 1991 and 2007 and she was a legend,” says Watson, who’s spent the last five months preparing for an upcoming Vienna show. “She discovered Jean-Michel Basquiat, she discovered Barbara Kruger, she discovered Jeff Koons and she discovered Jenny Watson.”

“I worked in a big loft on Wooster street and was at her country house on weekends. It was the most wonderful way to feel like I was a New York artist. Of course, you get knockbacks and feel like a nobody but you also don’t know what will happen. My first New York show, I met a man with a walking stick [who liked my work] and he was Taylor Mead, a muse of Andy Warhol! Of course, I’m homegrown, we have a very healthy scene here and I could never write off Australia. But you do have to realise its place in the scheme of things.”

What does Watson think about the Tumblr-era burst of female expression, the new generation of plucky young women who openly make art about their ordinary lives? “When I started, I felt like I was kicking in doors but now young women have a license to do anything. I teach and see some of it and I think some of it is way too personal. I never wanted my art to be an open book,” she says. Then again, it’s not as if she’s a stickler for rules herself. “When my work was becoming conceptual, my dealers were worried, but I was up and running by then! It was so exciting, it was so connected to the music.” She pauses and breaks into a grin. “There was no way I could have ever gone back.”

The Fabric of Fantasy is curated by Anna Davis and shows at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney from July 5 to October 2, 2017.

Credits

Text Neha Kale