This article was originally published by i-D UK.

I often find myself at odds with friends or colleagues whenever they launch into a tiresome, “It was so much better in my day” tirades. Typically, this happens when the subjects of music, fashion, and clubs arise. The latter two topics, in particular, tend to provoke my fashion-loving friends into misty-eyed dissing of the youth of today, whose after hours attire and antics in London’s more off the wall nightspots are casually dismissed as derivative or irrelevant. I reckon they’re just jealous — because they are no longer young or resilient enough to maintain the pace. No longer do they possess that un-self-conscious ability to fling on some old rag rummaged from, say, Dalston’s Ridley Road Market, re-imagine it as a “look,” then subsequently wow all and sundry with it on the dancefloor (six months later seeing it emulated upon a catwalk).

Despite the ageing doubters bending my ear, I still firmly believe the worlds of clubs and fashion need to collide and collude. Firstly, because it is fun, of course. Also, it is not as shallow as some claim. In fact, it is one of the few fairly unregulated territories where new and creative ideas about style can percolate and different ways of living and being can emerge. Without such a nocturnal laboratory, fashion would be considerably impoverished — especially the collections coming out of London, a city famed and envied around the world for its brilliance and originality.

This is a view shared by one of London’s most well-known and much loved club “faces” – Princess Julia. The DJ, model, writer, long-term i-D contributor, style icon and fashion muse’s dedication to “going out” non-stop since the late-70s is pretty much unparalleled. “The most inspirational designers always dip into club culture. It’s a rite of passage,” she says. “Currently and perhaps most obviously, Charles Jeffrey took inspiration from his club night LOVERBOY and turned it into the basis of his debut collections after leaving college.”

If you follow this trajectory across the past 40 odd years, there are pivotal moments when clubs and fashion intertwined in the capital, facilitating crossovers, collaborations, camaraderie, careers and clothes — all ultimately of benefit to the wider fashion industry. Anyone with access to archive issues of i-D will find these momentum-gathering creative relationships profiled, photographed and editorialized, long before the mainstream media and fashion industry became fully aware of them.

Clubs and fashion have intertwined in London for over 40 years, facilitating crossovers, collaborations, camaraderie, careers and clothes — all ultimately to the benefit of the wider fashion industry.

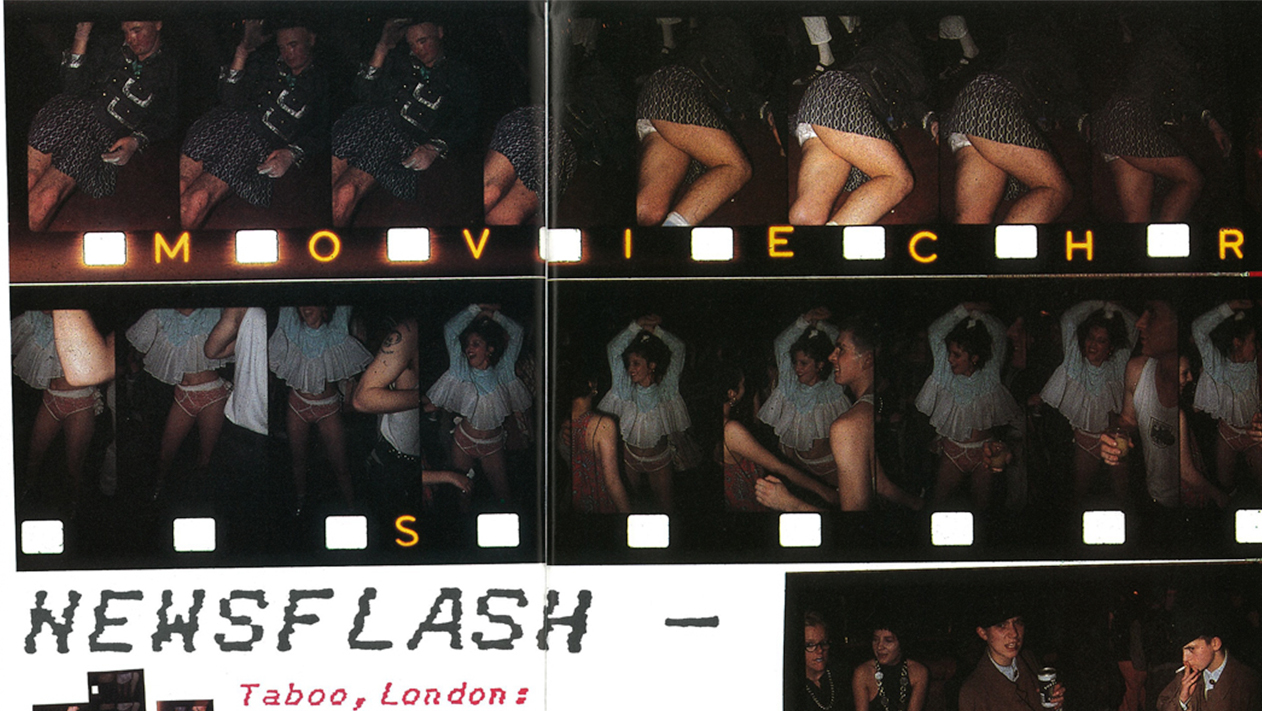

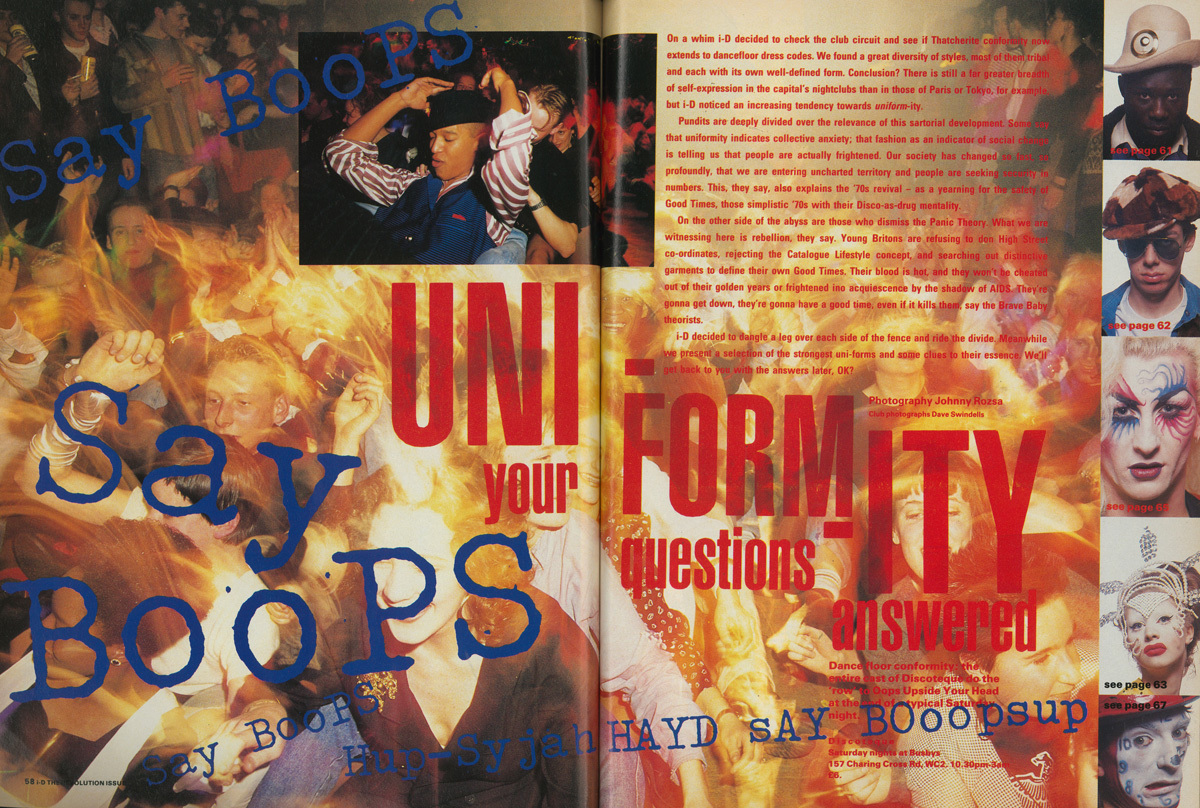

From the late 70s to the late 80s, club nights impacted massively upon fashion and the media, fostering new designers, stylists, boutiques, and publications. Billy’s, then Blitz, founded by Steve Strange and Rusty Egan in the late 70s and early 80s, respectively, and Taboo, launched by Leigh Bowery and Tony Gordon, in 1985, are particularly mythologized for their pioneering spirit. Original Blitz kid, Iain R. Webb, who went on to become Fashion Editor of Blitz and then The Times, and is currently a curator, author, and professor at the Royal College of Art and Central Saint Martins, remembers the impact that he and his talented generation of hard-clubbing friends created: “The attention of the international press was pretty remarkable with photographers and camera crews that turned up at the clubs — oh, how we posed! And uptown top ranking editors filling the front rows at fashion shows by Bodymap, Richmond Cornejo, HyperHyper, John Crancher, Colin Swift, John GalIiano, John Flett, and Rifat Ozbek,” Ian remembers. One standout moment: “In 1986, Hebe Dorsey, the grand Fashion Editor of The Herald Tribune, wrote about the three new style magazines: BLITZ, The Face, and i-D. She described the new approach as, ‘blissfully liberated with a lot of fun-poking at the Establishment.'” (Such is the creative significance of this era, the V&A Museum even dedicated an entire exhibition to the theme, in 2013, titled Club to Catwalk.)

The designer, archivist, and style icon, Michael Costiff, and his late wife Gerlinde, ran Kinky Gerlinky, one of London’s most notoriously riotous and dressed-to-kill club nights through the late 80s to the early 90s, attracting up to 3,000 revellers to the monthly parties during its peak. Jostling for attention on its dance floor were scores of wildly styled club kids, drag queens, and flamboyant freaks alongside more well-known fashion figureheads. These included Vivienne Westwood, Jean Paul Gaultier, Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, Pam Hogg, Leigh Bowery, Philip Treacy, and Stephen Jones — in addition to models such as Naomi Campbell and Kate Moss and Fashion Editors like Hamish Bowles. It is not hard to imagine how much inspiration they must have found there, whether for their subsequent collections or magazine shoots. (Indeed, British Vogue recently paid homage to the night, in a Mert & Marcus shot series of images, styled by Kate Moss, in their March 2017 issue). “At Kinky Gerlinky there were always such incredible and inventive looks to be seen,” Michael recalls. “People spent weeks preparing their outfits and getting ready was a big part of the fun. It was a time when pop videos were important, the supermodels ruled the catwalks, and Madonna ruled the charts. Glamour was in the air and Kinky gave you a chance to share in that world.” On a more sobering note, Michael puts into context the need for nocturnal escapism underpinning the 80s and 90s. “This was a time when the horror of AIDS was still in full force, ripping through our friends and community,” he explains. “It made it even more important to have a place where you could step out of yourself, forget about the outside reality, be ridiculous, dress to the nines, and have a ball.”

Throughout the latter years of the 20th century and earlier 21st Century, a roll call of experimental London club nights successively impacted upon the collections later presented at London Fashion Week, as designers took their cues from what they saw on the dance floor. These ranged from Smashing, Popstarz and Blow up, to Kashpoint, Trash, NagNagNag, and All You Can Eat. The love affair between clubs and fashion peaked once again, ten years ago, at Richard Mortimer’s legendary club night, BoomBox, packed full of club kids, fashion students, and the British fashion industry’s rising and established stars. Charlie Porter in The Independent in 2007 accordingly noted: ‘BoomBox has symbolized a new surge of creativity that has reawakened London’s fashion set. The buzz names on this week’s London Fashion Week schedule — Giles Deacon, Gareth Pugh, Kim Jones, Henry Holland, Cassette Playa — are all regulars.

This same energy has attracted the newest generation of image-makers and fashion-influencers to nights such as LOVERBOY, as well as Sink the Pink and Savage, in east London. And those fierce club looks linger way beyond the strobe lights nowadays, shared across Instagram accounts galore for all to see. While previous generations had to deal with the terror of AIDS and the reality of friends and loved ones dying way too young, other challenges of a less extreme yet still problematic nature routinely face today’s generation of young creatives in the capital. Especially those from working class backgrounds. Basically, how the fuck do you afford to live in this city unless you are rich? A lot has been written of late about the increasingly rampant pace of gentrification in London. This has caused many much-loved pubs and club venues to close — most notably The George and Dragon, The Joiners Arm, Madame Jo Jo’s, and Plastic People — and many creative scene-makers have been left with no option but to move to the margins of the city, making it ever harder to sustain a community.

In the early 00s, I wrote about gentrification in i-D — imagining a worse case scenario, in which all of us oddballs end up being shuttled back to the small towns and suburban enclaves from which we originally sought to escape. I was being a bit facetious — little did I realize it might so quickly become a reality. Even a decade ago, it was still reasonably plausible that kids could squat abandoned buildings for a reasonable amount of time before being booted out, unlike now, whereby the authorities swiftly enforce eviction. The south London !WOWWOW! collective birthed the early work of Gareth Pugh, Matthew Stone, and Hanna Hanra among others, from their abandoned department store squat. Very few of today’s burgeoning designers live rent-free.

A huge downside to this displacement is it discourages young people from moving to the capital, in particular to go to college. Applicant numbers are declining for arts-based degree-level courses at many academic institutions across London – not only from international contenders understandably perturbed by Brexit, but from UK hopefuls, too, aware that the cost of living here is becoming as sky high as all those luxury apartments that dominate the city.

When I talked to some marvellously over-dressed, gender-blending, makeup splattered fashion students recently, it was apparent how much of a struggle they found it to stay afloat in London: juggling their full time studies with part time jobs, paying eye-watering rents to live in dismal dumps in Zone 4, managing escalating levels of debt and related anxiety — and trying to still maintain some kind of inspirational social life which can feed into their work. The London they had hoped for and read about — in their teenage bedrooms, far away, when they were still outsiders dreaming of meeting creative kindred spirits — is under threat, big time. In a LOVE magazine interview with Fashion East’s Lulu Kennedy, the designer Charles Jeffrey captured that exact yearning. He recalls his own past as a teen misfit in Glasgow, romanticizing from afar: “I was 17 and not a lot was going on. I’d be on MySpace all the time, seeing Gareth Pugh and BoomBox and being like, ‘I really want to get to London!'”

Ingeniously, Charles funded his MA at Central Saint Martins, from which he graduated in 2015, by running his own popular club night, the aforementioned LOVERBOY, at east London’s Vogue Fabrics. The links between his designs and his nightlife are therefore plain to see. They provide a stark reminder of what London can produce, against the odds. As Iain Webb puts it, “The London club scene has always offered a safe haven for folk who don’t fit — misfits and outsiders who inhabit the outskirts of society be it culturally, sexually, racially or politically. Fashion has always been inspired by the demi monde. The titled stylist and poverty stricken designer cavorting on the dance floor, dressed in a handful of illusions… In 2017, the London club scene still embraces the radical and celebrates diversity. The merry dance goes on.”

For how long is anybody’s guess. Without wishing to be too pessimistic, the next Charles Jeffrey — when he or she weighs up the odds — might be more inclined to pursue their creative dreams and ambitions in a different city, or even another country, one that is more affordable and values their talent. If that happens, the rich tapestry of London’s clubs and its fashions might start to unravel. For now, the only thing to do is keep dressing up to the hilt, going out, having a scream, and hoping for the best. Your disco needs your ideas and energy like never before. And so, too, do those catwalks.

Credits

Text James Anderson