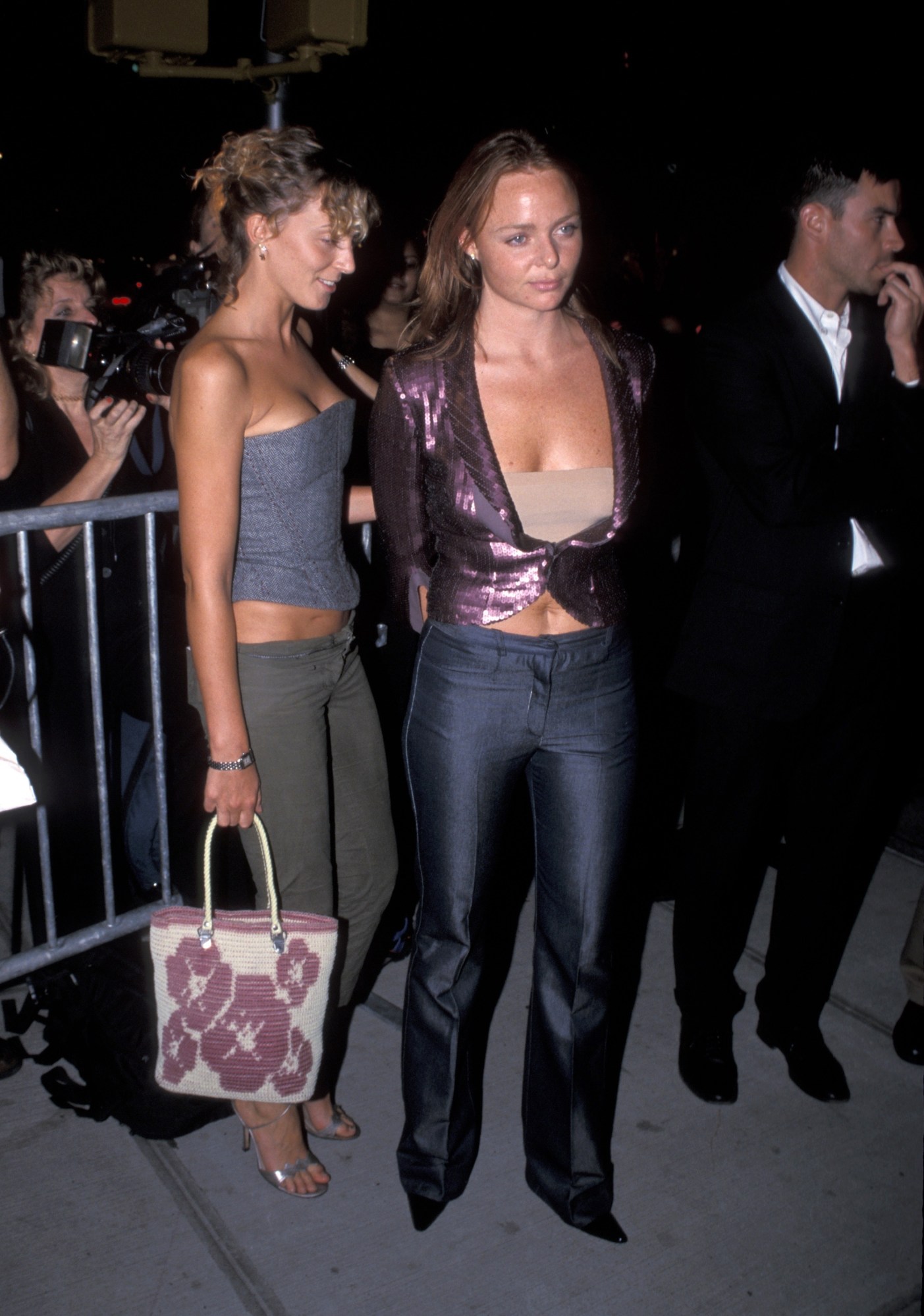

When Phoebe Philo arrived at Chloé in 1997, as deputy to creative director Stella McCartney, she had a gold tooth.

A photo from two years later shows both London-born designers in tight low-slung going-out pants and bustiers. They look more like members of All Saints than the custodians of one of Paris’s most historically demure fashion houses. Philo told The Guardian in 2005 that, back then, both she and McCartney spoke with “mockney accents” and that she occasionally had diamanté nails.

Today, Phoebe Philo the woman is synonymous with a specific kind of effortless sophistication, in the same way that her tenure at Céline has created a legacy of softly eccentric luxury. For roughly a decade, she has taken her post-show bow in a uniform of suit pants, wool sweater, and sneakers (AirMax or Stan Smiths) or minimalist round-toe black shoes. Somewhere in between her days of rocking lace-up bodices and her discovery of crewneck sweaters, something changed. And it’s impossible to miss how much that change is reflected in the clothes she creates: the frayed hot pants and gold lurex bikinis of y2k Chloé versus the restrained cool of her very first Céline collection, for resort 2010.

As fashion designers become increasingly public figures (sometimes even celebrities), it’s increasingly tempting to make connections between the clothes we see them wearing and the clothes they create. How has Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen’s evolution from bandana-wearing tweens to boho trendsetters to gatekeepers of good taste guided their brand? What does Rei Kawakubo’s monochromatic uniform say about her collections? Do these choices make statements at all?

Our interest in fashion designers began to peak in the supermodel era of the 90s. In 1989, MTV launched House of Style, giving a party-like glimpse into the world of models, designers, celebrities, and a new phenomenon: the celebrity designer. And in 1995, Unzipped became one of the first wide-release documentaries to capture the previously private creative world of a fashion designer: in this case, Isaac Mizrahi. We’ve been reading designers’ personal styling choices like fashion forecasts ever since.

Proof of the media’s intense scrutiny: Martin Margiela’s announcement, in the mid 90s, that he would no longer be giving in-person interviews or having his photograph taken. (There is only one known photo of Margiela’s face in circulation, taken in around 1997.) “It was not just for the sake of being provocative,” Patrick Scallon, the former director of communications for Maison Martin Margiela, told The New York Times in 2008, “A designer is not an artist in a gallery, not a sculptor with a chisel and stone in a garden.” Margiela was adamant that 1) the collections of Maison Martin Margiela were created by a team, not an individual, and that 2) they spoke for themselves.

While some designers shirked attention, others harnessed it to create global lifestyle brands of which they were the center. In the 1990s, Donna Karan, Ralph Lauren, and Calvin Klein leveraged their own personalities to multiply their fashion lines into empires, selling sheets, fragrances, and underwear for which they were living, breathing billboards. It is impossible to draw a line between Ralph Lauren the man, often photographed in head-to-toe cowboy denim, and Ralph Lauren the brand, which sells thousands of pairs of jeans across America each year.

And the more photos we see of designers, the clearer the connections become between the creators and their work. Designers today have even more intimate “personal brands” linked to their image. Marc Jacobs, Alessandro Michele, and Olivier Rousteing all have Instagram accounts separate from their labels’, on which they post images of themselves in trackpants, Halloween costumes, black tie, and workout wear – not just their own pieces. Last weekend, Marc Jacobs wore a fringed leather Western jacket and furry Prada Wallabee boots to a Pride Parade. He’s also been feeling black elastic headbands and dabbling in full drag. Will we see more wigs at his next show?

Related: The A-Z of Marc Jacobs

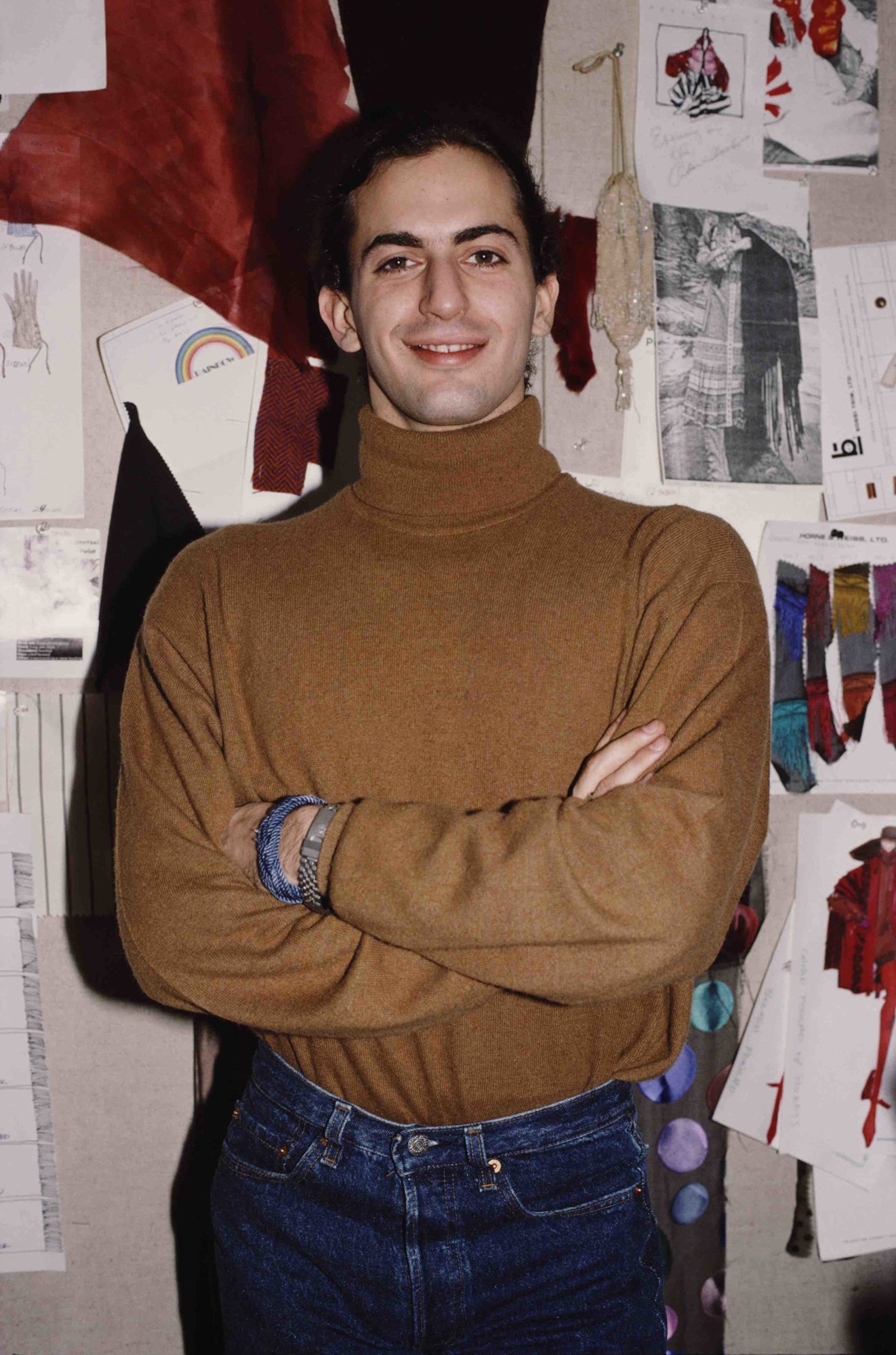

Jacobs’s personal style has evolved dramatically over his three decades as a designer, in ways that seem to correlate (sometimes clearly, sometimes obliquely) with his designs. He wore a smiley face raver T-shirt when he presented his graduate collection from Parsons in 1985, and maintained a kind of off-beat art student style throughout his tenure at Perry Ellis. The Dr. Martens and waist-tied shirts he wore could have predicted his iconic November 1993 grunge collection; that was the culture he emulated himself.

Four years later, around the time of his appointment as creative director at Louis Vuitton, Jacobs transitioned into slacks and button-downs Marc. He wore what felt like the uniform expected of a serious designer who had to navigate conglomerate boardrooms. In the early 2000s, his look moved towards that of a young Jonathan Franzen. His wooly scarves and reading glasses felt like an amusing foil to the glamor of his Vuitton extravaganzas. It seemed almost miraculous that a man who wore beaten-up sneakers with baggy formal pants was creating such impeccable and inspired clothing for worldly women.

That didn’t last long. More adventurous elements – blue hair! kilts! lingerie! – began to creep into Jacobs’s wardrobe (he’s spoken in interviews about the confidence that came with his significant body transformation in 2006), and also into his shows. In late 2012, he regularly began sporting pajama pants and shirts, which then turned up in Vuitton’s fall/winter 13 collection. He took his bow after his Marc Jacobs fall/winter 14 show in maroon Adidas trackpants and was later seen wearing them while walking his dog, Neville, in New York. At his fall/winter 17 show, almost all the models wore variations on track pants, many of them maroon.

Jacobs’s own passions and style unabashedly inform his collections. His ad campaigns starring his musician and actor friends are a testament to that. Like bonafide celebrity designers including Victoria Beckham, Jacobs uses his own personality and outfits to bolster his brand’s identity. (Beckham was also recently spotted wearing track pants, and also put versions in a recent show.)

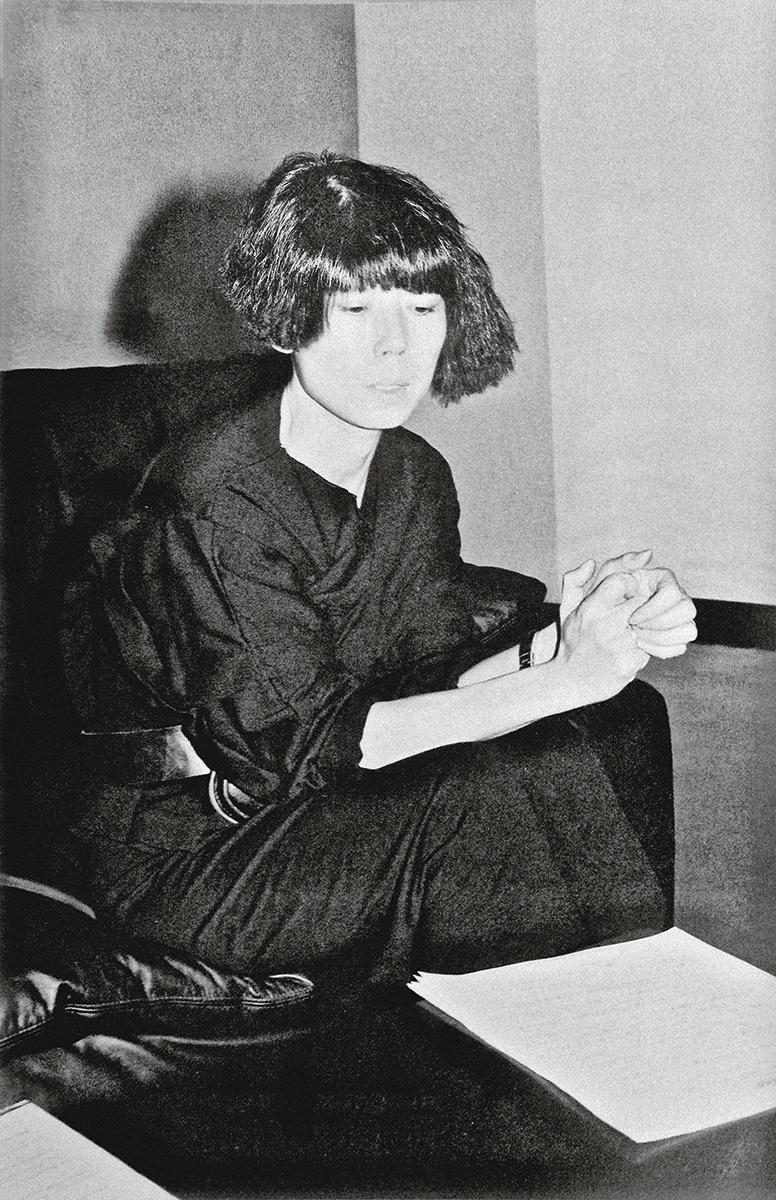

In the other camp is Rei Kawakubo. Kawakubo is subject to public scrutiny not because she freely shares her personal tastes but because she shields them. Her outfits seem to purposefully resist interpretation. Her routine look: black sunglasses, buttoned shirt, biker jacket. It is impossible to tell, by looking at Kawakubo’s outfit on any given day, what will spring from her mind next season. Her style has remained constant through her experiments with punk, pirate garb, and hunch-backed gingham dresses. She also has no desire to be a pored-over public figure (“NOT AT ALL. I HAVE NO SENSE OF THAT, AND AM NOT INTERESTED IN IT,” she recently told The Guardian, over email.)

And yet her gnomic approach to dressing tells you everything you need to know about Comme des Garçons. The brand too is not intended to be interpreted or defined. Its purpose is creating the new and transcendent by starting from scratch each season. Kawakubo’s own regular ensemble is the visual equivalent of that clear creative headspace: an unreadable blank space. Still, Kawakubo is insistent that she is first and foremost “a businesswoman,” and now that she is a retailer too (curating the merchandise at Dover Street Market), her personal style has further significance for her business. The designer wears Nike sneakers almost religiously; Nike has significant floorspace at Dover Street Market. It is a store where you can, in a sense, buy into Rei’s lifestyle.

Kawakubo’s preference for neutral dressing is shared by many of today’s most influential designers. Karl Lagerfeld has worn the same distinctive uniform (high-collared shirt, dark glasses, driving gloves) for decades. The Mulleavy sisters regularly take their bows after Rodarte shows in v-neck sweaters, denim shirts, and jeans. Adam Selman is usually dressed in dungarees and Converse. There’s a reason why fashion designers in movies are almost always played by characters with an eccentric, even monastic, taste for monochrome.

But that’s what makes the shifts and anomalies in designers’ wardrobes all the more telling. Marc Jacobs shed his glasses when he left Louis Vuitton, the Olsens swapped hobo bags for exotic clutches before starting The Row, and even Rei Kawakubo has recently been seen wearing a red biker jacket. In an industry focused on appearances, but still insistent on mystery, even the disappearance of a gold tooth is telling.

A bigger shift is underway now too, thanks to social media. Today, brands have ready-made “influencers” to help represent their brand, as well as their own designers. Hailey Baldwin, for example, has over ten times the Instagram following of Marc Jacobs’s personal account. And it’s certainly faster to gift a piece of clothing to a Snapchat star than to build a lifestyle brand from the ground up. Notably, the highly influential design team behind Vetements remains largely anonymous. Demna Gvasalia, the label’s head designer, doesn’t have a public personal Instagram. But Kim Kardashian’s Instagram photo of her daughter North West in Gvasalia-designed Balenciaga silver knee-high boots received over 2 million likes.

Related: The Work of Reticent Fashion Designer Rei Kawakubo Speaks Volumes

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Photography Francois Guillot for Getty Images