Sometimes you experience something alone, and later it feels like it’s everywhere you turn and inescapable. Almost exactly a year ago, during the weekend following the Brexit referendum, I found myself in Eindhoven taking in an exhibition that tracked the rebellious art underground movements of the 80s. There were the radical Dutch squatters and Spanish queer activists and the young Turks who resisted the country’s military coup. And there, too, were the generation of black British artists who fought against the racism of Thatcher’s government.

Despite the impeccable timing that leant extra weight to the show — it was at the height of the refugee crisis as well the moment Britain began its introspective turn by deciding to leave the EU — it felt strange that you had to go all the way to a small Dutch city to see this incredible generation of British art and artists. These works weren’t on display at the Tate, were barely being acknowledged by most institutions, and were mostly ignored. It was a movement crying out for critical recognition and reappraisal. And then suddenly, it was everywhere.

The Place Is Here left Eindhoven and headed to Nottingham, and is now on at the South London Gallery and MIMA. But also; Lubiana Himid, a major figure in the movement, had two solo shows this year, and picked up a nomination for the Turner Prize. Hurvin Anderson, although not represented in the exhibition, also picked up a nomination. Mona Hatoum had a Tate retrospective last year. John Akomfrah represented Britain at the Venice Biennale. Isaac Julien’s works are on display at Victoria Miro at the moment.

The political situation of 2017 is ripe for the plethora of political voices The Place Is Here amplifies. We live, again, through Tory austerity, racist Tory policing and housing policies, racial violence, crackdowns on black culture; suited, if not jackbooted, crypto-fascists threatening to come in from the fringes to dominate the political mainstream. Our current PM, as Home Secretary, ordered a billboard campaign telling foreigners to go home or face arrest. These concerns more or less mirror the situation when the black British art scene came to prominence in the early 80s amongst Thatcher and the National Front and racist police and racial inequality too.

Rasheed Araeen was one of the earliest figures to resist and formulate a uniquely black British art proposition, in his 1977 work Notes Towards A Black Manifesto, he wrote of a British Art Establishment that existed to support its people. “The question now,” he states, “is who does it actually consider its people.”

“Being written out of history can happen to you,” Maud Sulter wrote in Feminist Art News in 1988, as the scene was tailing off. “There is no safety in collusion with those who want to suppress our art and suppress our voices. They will turn their weapons on you.”

The Place Is Here is a chronicle of the intervening 11 years. Of a generation of artists who tried to turn their weapons on the art establishment. It’s the story of a post-colonial reaction to finding out that surprise! The British Art Establishment in the 80s (or the establishment in general) didn’t consider black people to be British people. And a defiant desire to create their own.

The artists came from across the oceans of the crumbling British empire. John Akomfrah from Ghana. Mona Hatoum a Palestinian refugee. Lubiana Himid from Tanzania. Keith Piper grew up in an Afro-Carribean family in Malta before moving to Birmingham. Rasheed Araeen emigrated to London from Pakistan. Gavin Jantjes from South Africa.

The persistently nagging question they pose seems to be: how do you link the colonial past of Britain and its racist present with the desire for self expression within that system? How do you place yourself within a present that wants to destroy you and your connection to the past? How do you make art in that situation? What art do you draw on for influence? Where do you find yourself represented?

There are no easy answers, and no right answers either, so The Place is Here becomes a chronicle of the myriad forms and styles that became the response. Is the violence of everyday life too much? You can understand art’s retreat into symbolism, mythology, beauty. Is the violence of everyday life too much? You can understand that documentation is enough. Paint what isn’t painted and show what they try hide and tell the story even if no one is listening.

Or, as Lubiana Himid writes in one painting (text is a forceful motif that runs throughout these artists’ work) from which the exhibition takes it title: “we will be who we want, where we want, with who we want, in the way we want, when we want and the time is now and the place is here”. Or, to summarise, racists go fuck yourself. The poem is written across the body of a black woman, arms crossed is obstinate, unmoving resistance. On her dress, beneath the poem, a collage of famous black cultural figures.

The black body is central to the exhibition, because of its glaring absence from British art history. Keith Piper’s The Body Politic, for example, is a painting of a white female and black male nude that examines the different gazes, desires, and exploitations the world places upon their bodies. “I was your best fantasy and your worst fear. Everything to you buy human” the text reads. These are the two stand out works from a show full of stand out works. Mona Hatoum’s Roadworks, a video of artist, in the days after the 85 Brixton Riots, walking barefoot through the streets, a pair of DMstied to her ankles. The symbolism is obvious right? DMs being the favoured footwear of the knuckle dragging racist skinhead, echo her steps, follow her around, impede her movement. Isaac Julien’s photo-series and feature film Looking For Langston, a mediation on black gay desire in Harlem in 20s find a pan-generational and international space of love, resistance, and expression.

Or Sonia Boyce, who reconfigures William Morris’ arts and crafts to bleakly tear at the symbolism of imperialism in Australia, India and South Africa. Eddie Chambers, whose work pays tribute to the joint icons of reggae singer Burning Spear, and black nationalist Marcus Garvey. There is anger and energy that ripples through the show and it is both exhausting and exhilarating.

Beyond the solidity of the works, the other thing The Place Is Here does so well is assemble an archive of the ephemera and activities these artists engaged in through self-organised groups and self-run galleries. Together they ran art spaces and established libraries, organised conferences and reading groups and symposiums throughout the 80s.

In response to a world that ignored them they created a rival Black British Art Establishment. The power though, is that it was no ivory tower bullshit art establishment, it was art that came out of the problems of the real world, responded to the problems of the real world, actively opposed them, took a stand.

The 80s was a decade of disturbance and acrimony brought on by violent, racist police officers and a violent racist state. In 1985 alone, Brixton, Handsworth and Tottenham all saw riots. Brixton and Tottenham were started by the deaths of innocent black people at the hands of the police. One work in the exhibition is by the Ceddo Film and Video Workshop, who captured the Tottenham riots and their aftermath. It was commissioned by Channel 4, who refused to air it, because they felt it accused the police of wrongdoing, and in the same action revealed the theoretical impossibility of institutional racism in the mind of someone in power.

The same year the Black Audio Film Collective made Handsworth Songs, directed by John Akomfrah, which used montage, newsreel, interviews, reportage, newspaper cuttings, and memorably, a dub reggae steel band version of William Blake’s Jerusalem, to tell the story of the riots in Leeds.

Handsworth Songs isn’t included here, what is though, is another work by the Black Audio Film Collective; 1989’s Twilight City. A harrowing 50 minute long meditation, in the form of a letter from a daughter to her mother in Dominica, that reflects on the racism of the Conservative government’s programme of regeneration and gentrification and renewal. It’s about home, what home means, how home changes. Or maybe, as Lubiana wrote, in 1985, for an exhibition of her work at the ICA; “We are claiming what is ours and we are here to stay.”

A nice coda for an exhibition that says, for all the times the black British art scene was ignored or left unloved, it’s survived, it’s here to stay.

southlondongallery.org/theplaceishere

Credits

Text Felix Petty

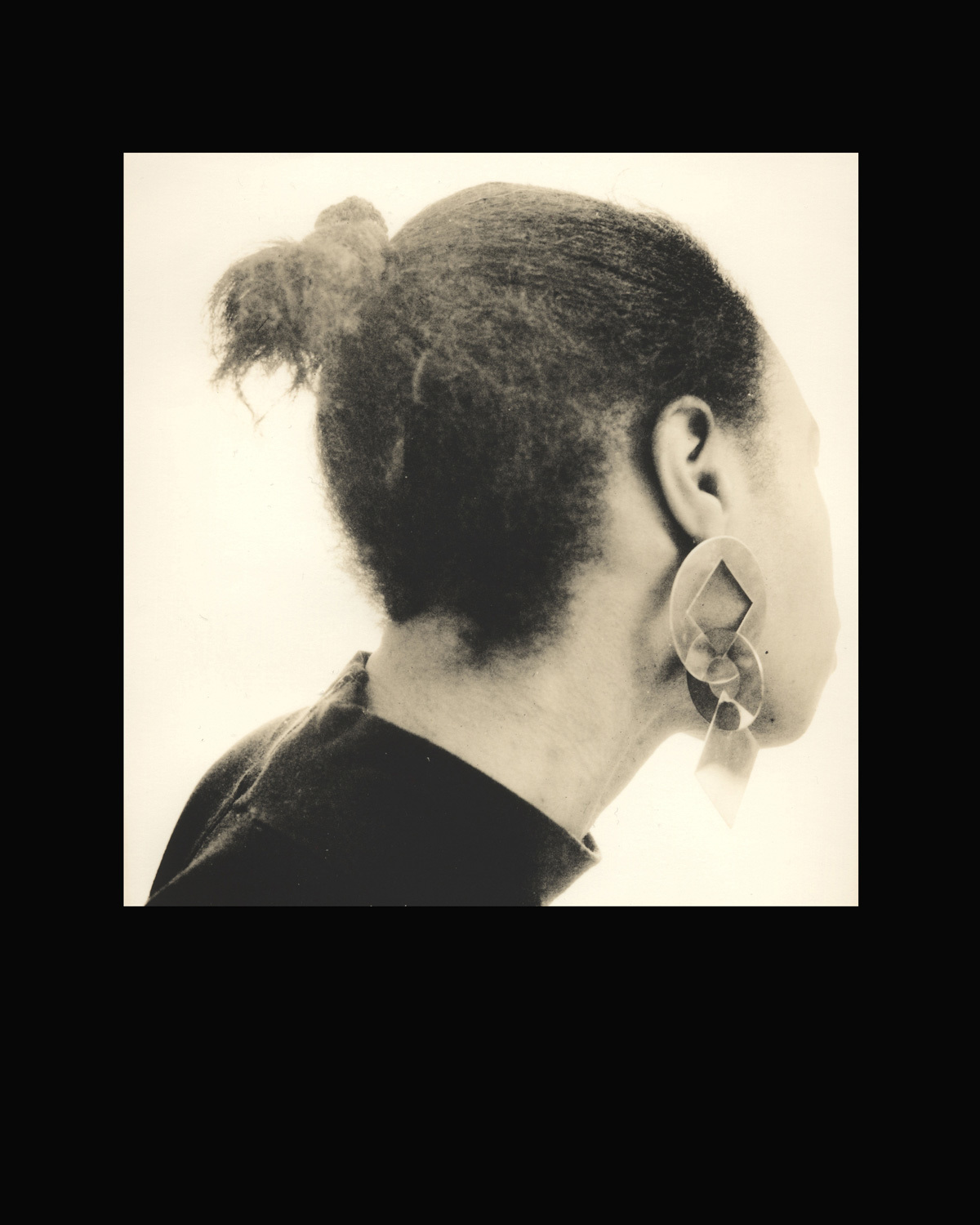

Lead image actress Corinne Skinner-Carter in Dreaming Rivers by Martina Attille. Sankofa Film and Video Collective (1988). Photography Christine Parry