i-D Hair Week is an exploration of how our hairstyles start conversations about identity, culture, and the times we live in.

An iconic video of Kathleen Hanna taken at the heyday of the riot grrrl movement shows the Bikini Kill frontwoman barking into a microphone while wearing a mustard yellow crop top and a pair of underwear. In contrast to her outfit, her dark hair is pulled into pigtails and accented by two light pink ribbon bows. The photo depicts a common paradox in riot grrrl style between the revealing sexualized outfits and the wholesome infantilized hairstyles that both served as a visual expression of their feminist politics.

The underground riot grrrl movement emerged in the early 1990s led by a new generation of female punks. Their radical feminist politics were reflected in their zines, music, and even their hair. Many riot grrrls would sport their locks in pigtails or ponytails adorned with colorful plastic baby barrettes—styles that were associated with little girls, but the hyper-feminine ‘dos were used as a way for them to reclaim girlishness.

“There were a lot of times that the idea that being or girl or young woman is something that was put down,” shares musicologist Elizabeth Keenan. “Girl things whether it was the color pink or wearing barrettes in your hair or being emotional about something, those ideas were generally discounted in society at large and even slightly in the feminist movement.”

While not all riot grrrls adopted “girly” hairstyles that incorporated clips and bows with their pigtails and baby doll bangs, many did. Niki Elliott accented her bright red bob with a pink plastic barrette during Huggy Bear’s performance of “Her Jazz” in 1993 and early photos of Bikini Kill show bassist Kathi Wilcox sporting short pigtails tied back by silky ribbons. The hairstyles visually connected them to young women, who were at the center of the underground movement.

“It was wearing girl style, but doing it slightly off-kilter. Not like when Britney Spears came out in her schoolgirl uniform (and braided pigtails) that sexualized girlhood in a pretty familiar way, like trading on the erotic fantasies of the willing girl or coed,” Gayle Wald, a professor at George Washington University and co-author of Smells Like Teen Spirit: Riot Grrrls, Revolution and Women in Independent Rock, explains.

This importance of girlhood is reflected in the riot grrrl name, which was chosen to put the focus on girls rather than women, since this was a time they often felt most insecure. As the movement’s original manifesto written by Hanna states, “we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.” By reclaiming these hairstyles as adults, riot grrrls gave new power to what it meant to be a girl.

“It was transgressive because they were refusing a corporate view of womanhood, because for white women in the 90s the idea that a ponytail is an infantilizing hairdo made it not what a serious woman in the corporate marketplace would wear,” said Wald.

Riot grrrl marked the beginning of a new wave of feminism, and leaders like Kathleen Hanna aimed to change the way feminists viewed womanhood after the second wave. The previous generation thought of “girl” as a belittling term and worked to be called “women.” Many second-wave feminists also criticized things like fashion and beauty as being tools of oppression. But, riot grrrls reclaimed girl culture and unapologetically embraced sexuality and femininity.

As Marisa Meltzer explained in her book Girl Power: The Nineties Revolution in Music, “With riot grrrl you could enjoy the playful aspects of being a girl and want to fight the power at the same time.” These infantilized hairstyles were sometimes countered by riot grrls writing words like “slut” or “whore” across their stomachs. As Meltzer said, “They were heavy-loaded, often ironic symbols, but symbols that nonetheless created a gulf between their feminism and their mothers’.”

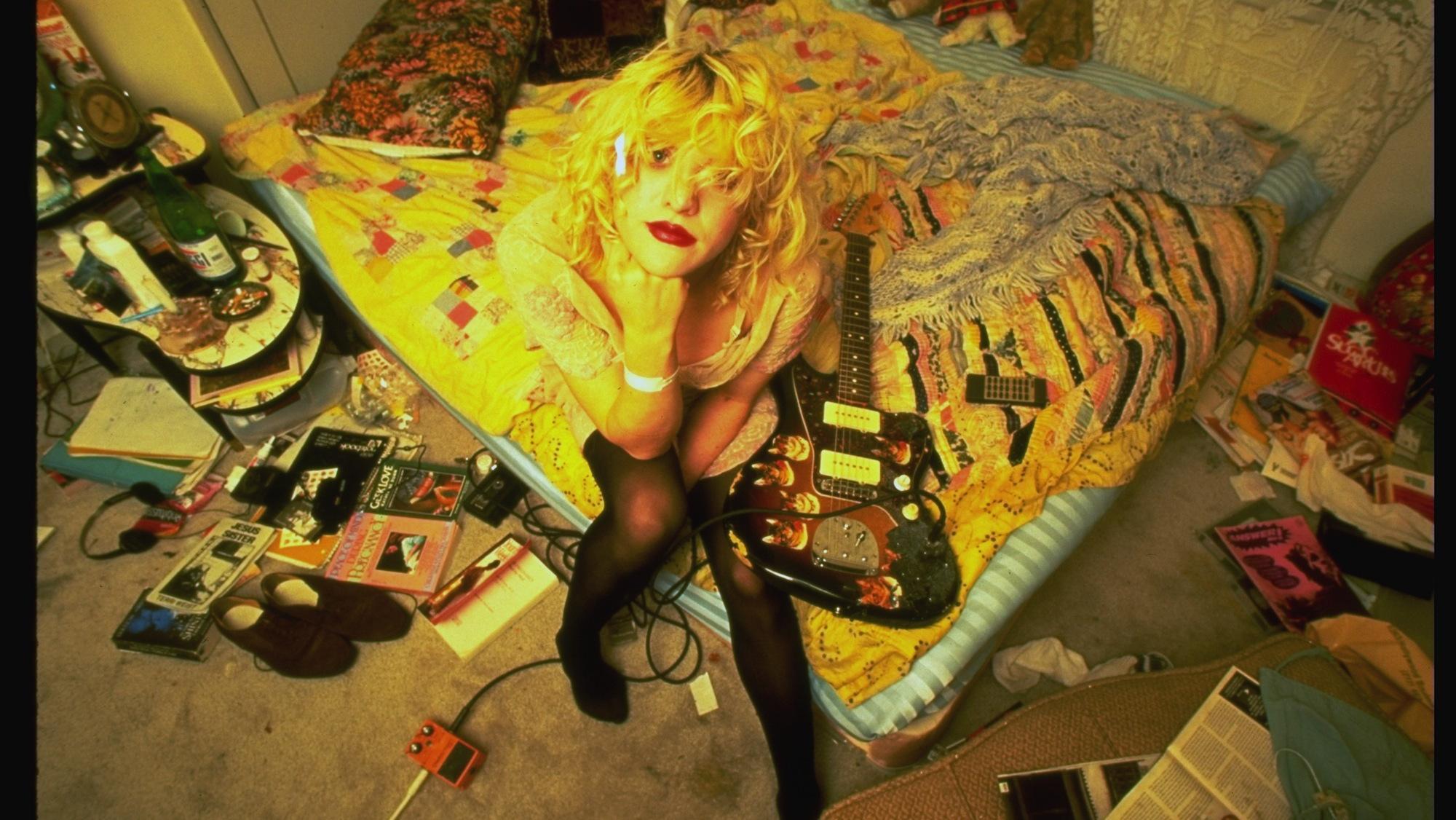

Out of the riot grrrl movement, and those often associated with it like Courtney Love, came the “kinderwhore” look, which popularized colorful barrettes and pigtails. This aesthetic parodied girly style, but added subversive elements like short dresses, ripped tights, and combat boots.

The youthful hairstyles were symbolic of the fun and lightheartedness of girlhood that the movement tried to preserve. Bands like Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, and L7, addressed the serious issues faced by young girls like sexual harassment, access to abortion, and domestic abuse, like in Bratmobile’s track “Do You Like Me Like That” where Allison Wolfe sings, “You don’t know what it’s like to be harassed all day, then to be told that you’re only in the way./ We’re living in fear, trying not to disappear.”

“My sense was that riot grrrl had such a potent critique of girlhood as a space of innocence and nostalgia,” says Wald. “Riot grrrl was really invested in making forms of abuse of girls visible, specially sexual abuse. But, also thinking about the ways that media created the culture of eating disorders and the idea that girls’ public spaces weren’t necessarily protected spaces.”

The childish aesthetic also allowed those like Hanna to reflect on her own girlhood. “I had a very dysfunctional family, and I felt very numbed-out for much of my childhood, and I felt like I missed a lot,” Hanna told T Magazine, adding that the style allowed her to express herself in a way that her childhood hadn’t allowed.

Riot grrrls aimed to attract other young women and create a community and a safe zone, which was especially important in the male-dominated realm of punk rock. These safe spaces offered women a place for self-expression, where there was no competition or jealousy.

“Riot girrrl was calling on a younger audience and kind of recognizing that audience as kindred spirits,” explains Keenan. “It wasn’t about going out and being a tough rocker chick, it was about speaking to an audience that maybe was like them and really giving space to girls within punk rock.”

As the movement gained an international following, it wasn’t long before the music and fashion industries caught on and commodified the girly aesthetic. This reclaiming of girlish hairstyles like pigtails was co-opted by groups like the Spice Girls and mall retailers like Limited Too marketed “girl power,” but without the radical politics.

Still, riot grrrls wearing infantilized hairstyle like pigtails or “Hello Kitty” barrettes made a powerful statement about girlhood, and how young women are viewed in society. As Wald says, “I think reclaiming stuff that looked girly is troubling to the culture at large when you have women dressed as girls but exhibiting grow-up sexuality it brought attention to the culture’s sexualization of young girls in a way that you couldn’t deny,” which was inherent to the riot grrrl mission.

Credits

Text Erica Euse