This article was originally published by i-D UK.

In her first solo exhibition, The Cedar House, artist Christabel McGreevy, 26, presents a drawn offering of cherished objects found in her late grandmother’s home. Currently completing her MFA at the Royal Drawing School, the British artist runs clothing brand Itchy Scratchy Patchy with co-founder Edie Campbell, which she launched in 2015 shortly after graduating with her BA in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins. With a focus on decorative DIY customization, Itchy Scratchy Patchy further grounds Christabel’s vested interest in textiles, folk art, and embroidery — an interest equally shared with her painter grandmother, Anthea Craigmyle.

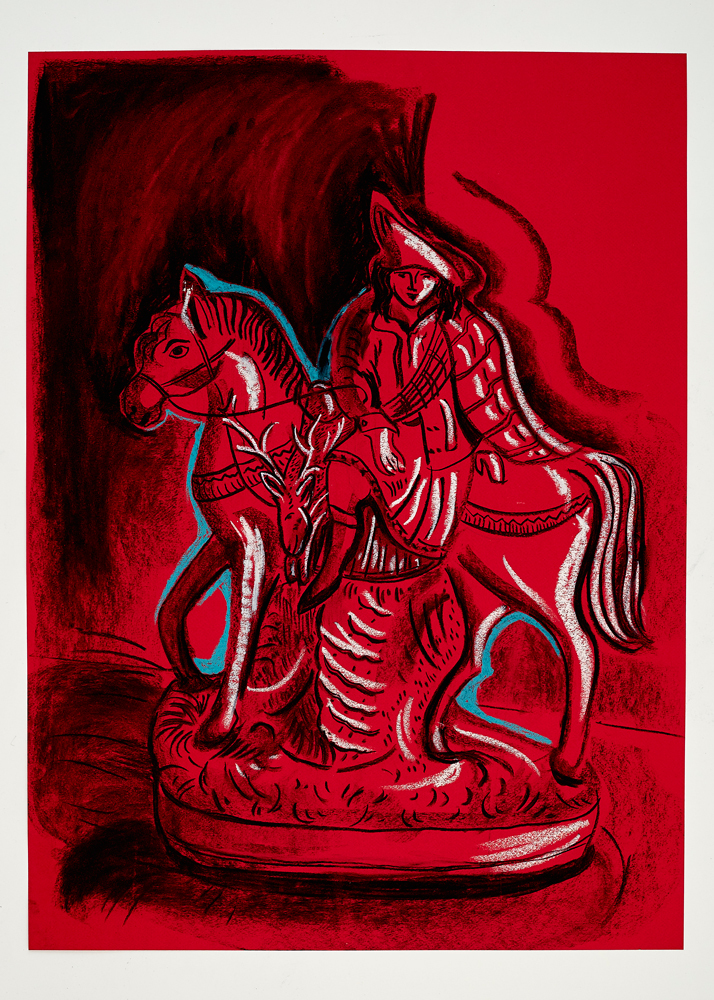

Avidly amassed over a lifetime, Anthea exhibited an enthusiasm for handmade or sculpted objects and filled her house with solid nude wooden figures, painted Staffordshire china creatures, religious effigies, ornate clocks, patterned rugs, and portrait busts — to name a few. Christabel explains the impetus behind her grandmother’s unique collection: “She grew up during the Second World War, which started when she was six and ended when she was 13, so she never received any Christmas or birthday presents when she was a child. When she was older she was obsessed with toys and you can see this in her collection.”

The project ultimately recalls the Italian academic Umberto Eco’s The Infinity of Lists, which examines moments in art history where “visual etceteras” abound. This investigation into visual representations of lists serves as a reminder that such collections far from represent an objective and finite register of items. Often simultaneously an accumulation of new treasures and a preservation of relics, the list remains subjectively and often arbitrarily composed by one individual. Especially in visual form, such an assemblage reserves an inherent potential capacity to grow and expand ad infinitum.

Extending a lineage of artistry while preemptively grieving the division of the collection among Anthea’s fellow grandchildren, Christabel chose to visually document over sixty of such items, launching a project that proposes listing as not merely a methodical system of cataloguing, but a practice of spiritual catharsis. She explains, “When everyone starting deciding to divide up all the objects — because they’d all been left to the grandchildren — I wanted to take control of them and have them for myself so that it wouldn’t matter when everything had gone. Drawing them was a way of somehow absorbing them within me. Because if you spend time with something long enough to draw it, the object becomes so indelibly ingrained in your memory that you sort of feel like it’s become a part of you.” In a cosmic display of patchwork color covering the walls of the gallery space, Christabel maps a nostalgic shrine in charcoal and oil pastel, first reincarnating then immortalizing her grandmother’s cast of characters onto a paper stage.

When asked whether she sees them as unified as one group of objects, the artist explains her decision to instead deliberately attempt to isolate each one. “I wanted to pull out each object one by one to put the spotlight on them, that’s why the backgrounds are quite flat and feel like a decorative field that something can be highlighted upon.” With a nod to her experience working in textiles, the degree of pattern-like detail of each drawing visibly develops as Christabel’s undertaking gains momentum. By forcing each composition to fit onto identically sized paper, the artist shrinks or enlarges each object to varying degrees, warping scale until everything equalizes within the picture frame. As such, a monumental wooden figure and a miniature china dog appear side by side, towering over the viewer as if lined up along an imagined mantelpiece or window ledge. Plunging her audience into immediate childlike reverie, Christabel engages an inner nostalgia for objects and memories conversely not our own. Consequently, both audience and artist reminisce at once: “I remember growing up going to museums in London and even if sometimes they seemed quite boring, I would find one object that I became sort of obsessed with. The idea that we create collections out of our own memories and these become miniature histories even within our own lifetime, represents the underlying feeling of this series of work.”

Credits

Text Antonia Marsh