In the late 70s, Australia was coming down from the protest movements that had spanned the globe the decade before. Post-hippy baby boomers crowded into capital cities, and took stock of the shape the world had settled into. While the 60s promised free love and a cultural revolution, the deluge looked very different. As the 80s loomed, nuclear middle class families took root in the suburbs, and it became clear the revolution that was promised had been diluted, and once again the world belonged to the passive middle.

But all was not lost in 1978, as Melbourne’s youth found respite from the creeping monotony through punk. Freshly imported from the UK, this new underground would eventually evolve into a unique local offering lovingly called art punk. The scene would come to encompass hundreds of young Melburnians, ranging from 14-year-old renegade kids to adults in their late 20s.

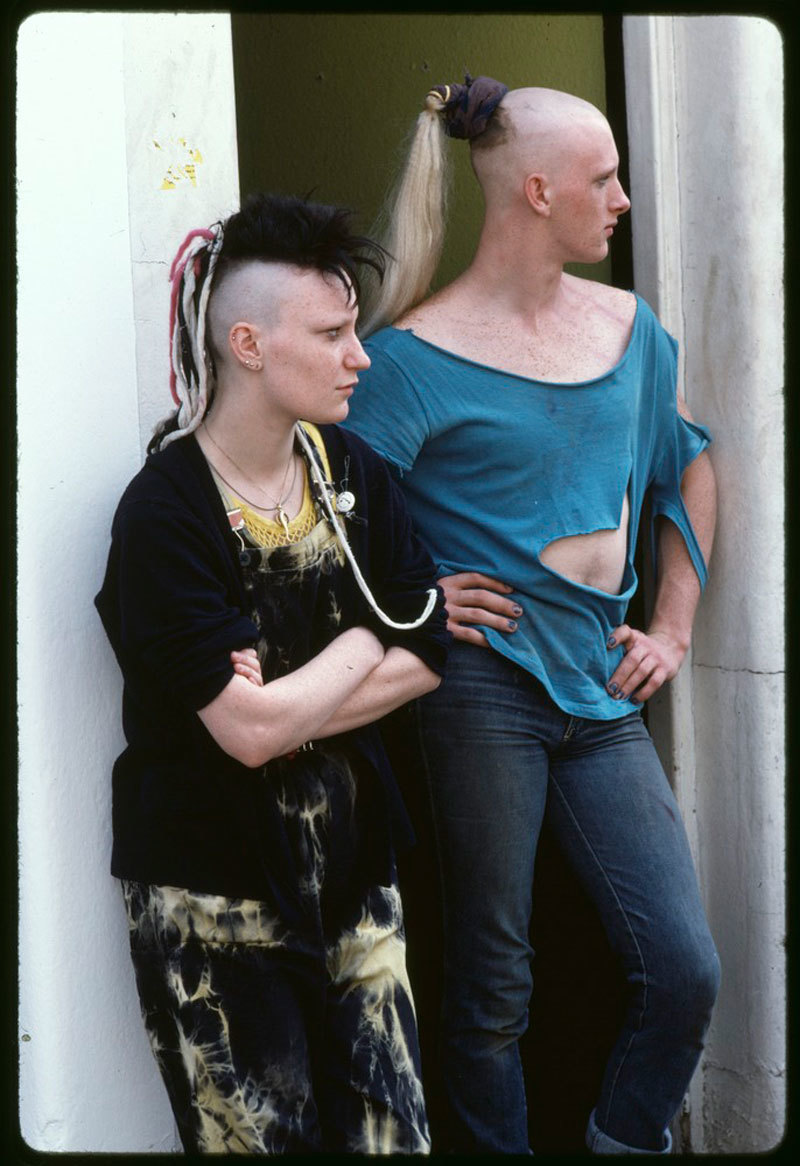

Clad in black, military civic service uniforms, accessorised with fetish elements of PVC and chains, Melbourne punks revolted against the perceived injustice of their social and political surroundings through music, art and fashion. As with most subcultures of the time, they also drew the attention of legendary social photographer Rennie Ellis who took to documenting their style around the city.

i-D caught up with some of the original scenesters to revisit this time, and get a sense of what was happening beyond Ellis’ images.

Sam Sejavka, musician in The Ears

What was life like when Melbourne’s punk scene first started?

In 1977, Australia was so different. Sydney was a cesspit and Melbourne was this conservative bastion. All you had to do was dress a little strangely – if you were a guy you were immediately a poof and if you were a woman, you were called a whore. It was a very, very conservative place. So when people caught onto the punk thing, when it hit, it was very controversial — more controversial than you can be today at any length.

Why do you think it started in Melbourne?

It was right for it because you had this generation of kids who were growing up in this really, grey dusty city. When it happened in England, it echoed over here. And music was so disco, there was no music worth listening too — it needed a good taking down.

Was it a political movement?

No amongst my lot. I mean it was all very anarchic – there were heavy duty socialists and stuff in the mix, but just the notion of politics was sneered at. Everything was sneered at, it was a sneering machine. The new generation wanted to break everything down.

Was there anything in particular you were rebelling against?

Apart from conservatism in general, I would say hippies because they represented the counterculture and they weren’t doing their job properly. Anything that vaguely was relevant to hippie-dom was sneered at. Like “love, peace, LSD” all of these things. It was nihilistic.

What kind of response did you get from general society?

If you walked outside you would get antagonised by people on the street. A lot of people would have a go at us for wearing bits of military uniforms. Some would even wear parts of a tram conducting uniform — any sort of uniform, and someone would take offence. There were a lot of people who didn’t like it.

Jenny Watson, visual artist and notable “punk it girl”

So how did you enter the punk scene?

I was walking into my new job at Caulfield Institute of Technology as an art teacher, and an 18-year-old Nick Cave was walking out because he was dropping out. I met this disgruntled youth, very punk, very London style in 1977, and he knew who I was because I’d had a couple of exhibitions so he asked me to come see his band – he was touting for an audience.

I went to probably his first night at the Tiger Lounge in Richmond where there were probably 30 people there – friends family and the odd fan, two dollars to get in, and the rest was history. I became a big fan and part of that Melbourne music scene that was growing by the second.

Tell us about Nick Cave and The Boys Next Door’s place in all this.

They were all part of a burgeoning subcultural scene that I believe happened because the suburbs of Melbourne — Box Hill, Doncaster, Glen Waverley, Caulfield – were settled by nuclear families after the war, living conservative nuclear family life with a 50s housewife running the house as far as the eye could see. That whole generation said “we don’t want to live like our parents” and I believe that’s what created this scene of art, music, fashion and film in Melbourne.

You were doing portraits of people from the scene, right?

Yes, I was so inspired by that scene and hanging around with the beautiful people I couldn’t not do these portraits. I painted Nick Cave and then girlfriend Anita Lane, as well as Sam Sejavka and many more. They were fabulous times. The conventional gallery scene was still showing fairly conservative paintings and sculptures, but there were places like ROAR Studios and Gertrude Street that showed more radical art and I was involved in ARTS Project, which was very important for the time and ran from 77 to 84. It was self-funded.

Why do you think punk was so important to youth culture in Melbourne?

Punk was connected with feminism, socialism, hippies – it was like every kind of social protest against middle class suburbia connected. It connected all the subcultures of the time. All of the people who didn’t want to live that middle class life were united.

Crusader Hillis, writer and co-owner of Melbourne’s queer Hares and Hyenas bookstore

What drew you to the punk scene?

In 1978 my partner Rowland moved to Canberra for study. During a semester break he came back to Melbourne and stayed with me at my share house. He brought with him Patti Smith, New York Dolls and Television records, and through one memorable afternoon we played them all and both instantly gravitated to the music.

What did being a part of the scene mean to you?

It was everything. It was a complete identity. Our black clothes and short hair and pale looks made us stand out, which we enjoyed. It was such a contrast to the hippy scene, which was still very big at the time, but starting to wane. It meant that you could go out every night to a band somewhere in Melbourne.

Were there sub-scenes within punk?

There were several different types of scenes in the punk and post-punk world. North of the city was more intellectual and experimental in its approach. It was also more working class in the north and most punters seem to have gone to a public school, and less went to private schools or art schools, which was a feature of the south.

Then there was the south-side art scene, where bands like Boys Next Door largely sprang from. Caulfield Art College was an epicentre of south-side punk, and several of the bands came from either Caulfield or the Victorian College of the Arts. There was always a strong connection between visual arts and punk, and later this spilled into performance art as well. You could go out to see a band at the Crystal Ballroom and catch a bunch of performance art downstairs as well. The same went for the north-side scene in many ways, which possibly had a stronger connection to Dadaist, absurdist and anarchist art as well.

What do you think set the scene apart?

Expectations and ambition. Our ambitions were for fun and adventure, and we rarely had expectations about how things were going to work out. This is also the time when the baby boomers handed over to the next generation, and we’ve seen from history that the generation following the boomers became a ruthless set of real estate-buying, ambition-oriented people who changed Australia from being a welfare oriented place — a tiny moment in our history — to a place where personal capital, celebrity and success were everything.

Beyond that there were the hippies, who for punks personified white privilege and heteronormativity masked as looking for freedom, but mostly for the men.

So punk offered more space for minorities?

I think it did, because it was about the commonality of music, dancing and socialising, and it was so loud and fast paced that factors beyond the scene never really dominated.

It never really equated to being an LGBT scene in any sense – the queers knew each other but were often in different friendship groups. It did not lend itself to categorising or gathering around sexuality issues, in much the same way that it didn’t around gender or class. Taste in bands and music were probably more important determinants in how you socialised.

Credits

Text Alexandra Manatakis

Photography Rennie Ellis/ Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria