Most major New York City art galleries — almost all of them located in Chelsea or on the Lower East Side — open new shows on Thursday evenings. There’s often free wine, and barely ever food. The only convention Larry Clark’s recent reception remained faithful to was the 6-8 pm time frame. White Trash made its debut on a Friday evening at Luhring Augustine Gallery’s Bushwick outpost, located on a stretch of Knickerbocker Avenue that scrap metal yards and concrete mixing companies call home. Budweiser was the beverage of choice, and food trucks were summoned to serve ice cream and Japanese tacos to gallery-goers. It seems the 74-year-old Clark is still having fun breaking the rules.

Like all the best shows, the most surprising, incendiary aspect of White Trash is the work it features. It’s all Clark’s, but he is not the author of most of it. Every piece has been culled from his personal art collection, amassed over the past 56 years. “Back in the day, when I had no money — nothing — I might see a painting and just had to have it. It was so difficult to get the money to buy it, but somehow I would.” Often, he’d make swaps with other painters or photographers. Other times, “I’d borrow money and not pay the rent, or max out credit cards. When you’re poor, they send you 12 credit cards a week.” He says he didn’t get one until he was almost 40.

Much of Clark’s collection is Art with a capital A. He’s got walls of Christopher Wools, Sue Williamses, and Andy Warhols. (Works by Jeff Koons, Helmut Newton, and David Wojnarowicz hang alongside them). There are also plenty of posters, for films like Panic in Needle Park and The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, and the L.A. punk band X. (Clark figures he’s got enough of these for another full show. “Movie posters, ephemera, punk rock flyers. I have stacks and stacks in my studio and it’s making me crazy!”). Still other works are more personal: the pale pink neon sign from one of Clark’s favorite record shops, a Supreme skate deck featuring a photograph from his career-igniting series Tulsa, even the old fire door from his loft. “I never collected with value in mind; I never bought something I thought would go up in value,” Clark says. “It’s all works I had to have.

This mix is what makes White Trash such a fresh and thrilling show. Everything we admire about Clark’s own work — its unflinching authenticity, its dark humor, its renegade spirit, its at-times unsettling beauty — can be found in the pieces comprising his knockout collection. “The work gives me inspiration — to make work, to move on, just to live. Any of our problems are fear-based. I look at the Christopher Wool FEAR every morning, and it keeps me going.” Another one that keeps him going, Clark says as he rolls up his sleeves to expose a block-letter tattoo just above his wrist: “‘keep punching.’ I wake up, look at that, and say ‘gotta keep punching, can’t give up yet.'”

Here, Clark shares the stories behind six of White Trash‘s best works.

Jenny Holzer

I’ve always admired her work. I photographed her, and I’ve been to her place in the country. And this [work] especially is something I’ve read a hundred times, a thousand times. It’s just so smart, incredibly smart. And she’d paste these up around. I also have this in Spanish — I don’t know if there are any [Spanish works] anymore. It’s a little smaller, but it’s the same one, in Spanish. I’ve had it for a number of years. Really wonderful.

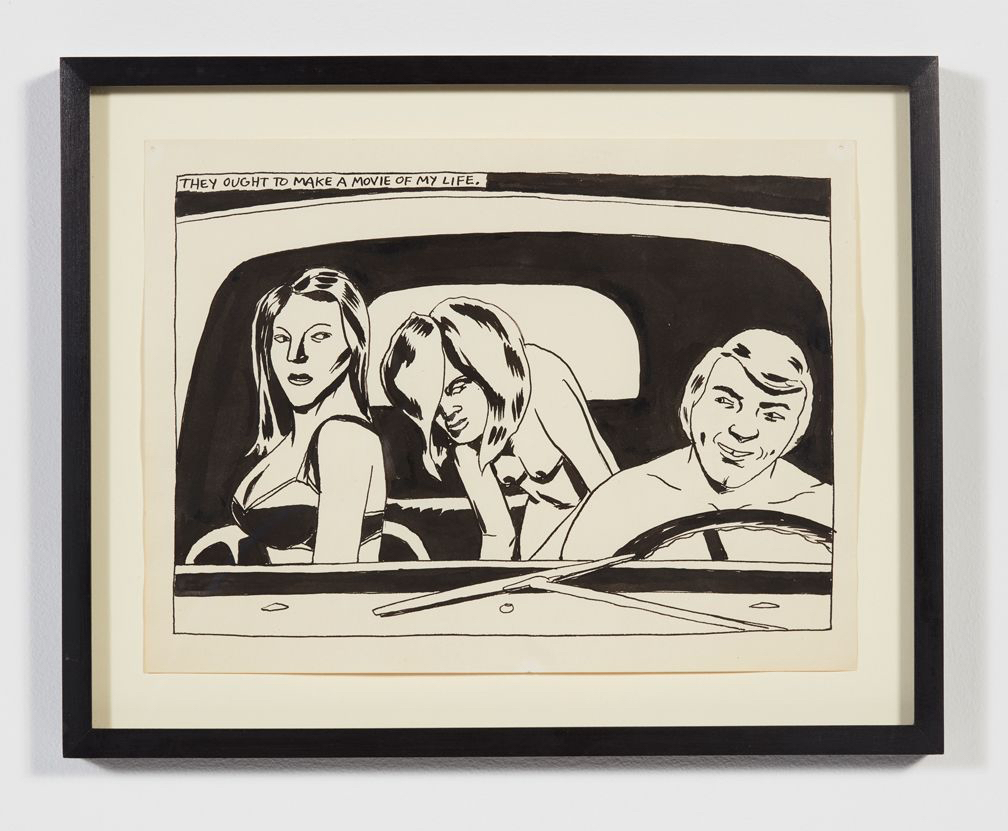

Raymond Pettibon

These are very early works. I bought these before he ever had a show in New York, from Hudson, who had a gallery called Feature Gallery on Broome Street, caddy corner from the Broome Street Bar. [Roberta Smith wrote about Hudson in The New York Times in 2014: “a former dancer and performance artist known only by his last name, who went on to become one of the most prescient, independent-minded and admired gallerists of his generation.”] I went over to see Hudson at Feature, and he had a box of these that he was going to show. So I bought these, all at the same time, before he showed them. I liked them because they’re so simple. There’s very little writing — almost none. And after [Pettibon] had a few shows, he started writing more and more. Now, he writes all over them — like a book, almost. Personally, I like the simple ones better. And I think that these are all incredible works. They’re so simple, but they all stand alone.

Bleecker Bob’s

Bleecker Bob’s was a record store on Bleecker Street forever that Bleecker Bob just closed recently. He was in the hospital — I think he had a stroke — and needed money to help recover. And a good friend of his owns Neon, the neon shop on White Street between Church and Broadway. I happened to pop in there one day because it’s a block from my loft, and I saw him there. He told me about Bleecker Bob, and that he was going to sell the sign and clock, and all the money was going to help Bleecker Bob. So I bought it, and feel lucky to have stopped by.

Will Boone

This is a Will Boone piece which [I found] only two or three years ago. I went into Karma, the bookstore, and he had a little show there — maybe six pieces. This is when Karma was on that little street in Village next to Cary Grant’s house. Which is still there — you can see the apartment building, about the size of a room, just stuck in between these other two buildings. [Grant’s former home is reportedly the most narrow apartment in New York City.]

Larry’s Door

This was the door to my loft. They were trying to get the building up to code and had the fire inspectors come in. It had a police lock on it, as you can see. It was a fire door, but the fire department said the door had to go, because it’s wooden inside. So they made me take my door down, and gave me a new one. I kept it, of course. And this was how I had it in my loft; I just moved it from my loft into the New Museum show [Clark’s door has been exhibited once before, as part of the New Museum’s survey NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, from 2013]. I made the wall piece on the spot. I took the material from my house and put it up in a day or so. It was fun to make a piece in the New Museum. Some of the stickers were put on by the kids in Kids. I might have put a sticker or two on there myself but they started filling it up when they’d come over. I loved the stuff that came out of the film.

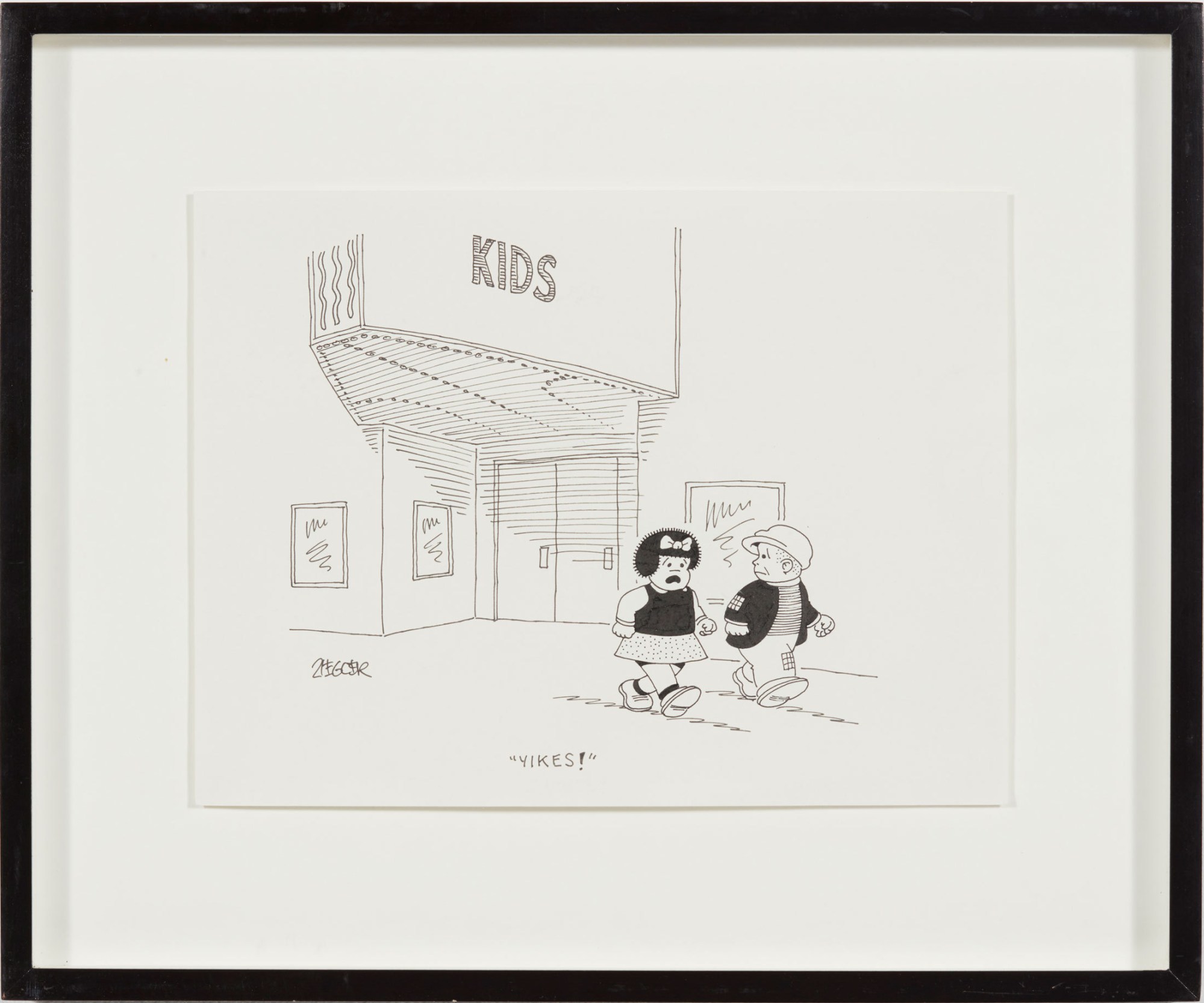

New Yorker Kids Cartoon

Ernie Bushmiller did Nancy [a long-running comic strip beginning in the late 30s], but this is a New Yorker cartoon by Jack Ziegler that came out the week Kids came out. I called Andrew Wiley, the literary agent, and told him about this cartoon. He called The New Yorker, got Ziegler’s number. I called Ziegler, who lived up in Connecticut, and I bought the cartoon. This is before people were buying cartoons. Now, I think, in The New Yorker they sell everything. But no one was buying them then, and I bought it directly from Jack for maybe $600, or 300, something. I grabbed it. It’s just so funny to me! And it was so hip, because you’d have to know Ernie Bushmiller, and Nancy, and Sluggo who I’m sure no one knows now. “Yikes!” It’s a great word. And I’ve actually used it a few times when I’m making films. Another one is “Hark!” which Little Orphan Annie used to say. She’d go, “Hark!” which means “shut up and listen.”

‘White Trash’ is on view at Luhring Augustine through June 18, 2017. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Lead image Larry Clark, “White Trash.” Installation view, Luhring Augustine, New York. Courtesy of the artists and Luhring Augustine, New York. Photography Farzad Owrang.