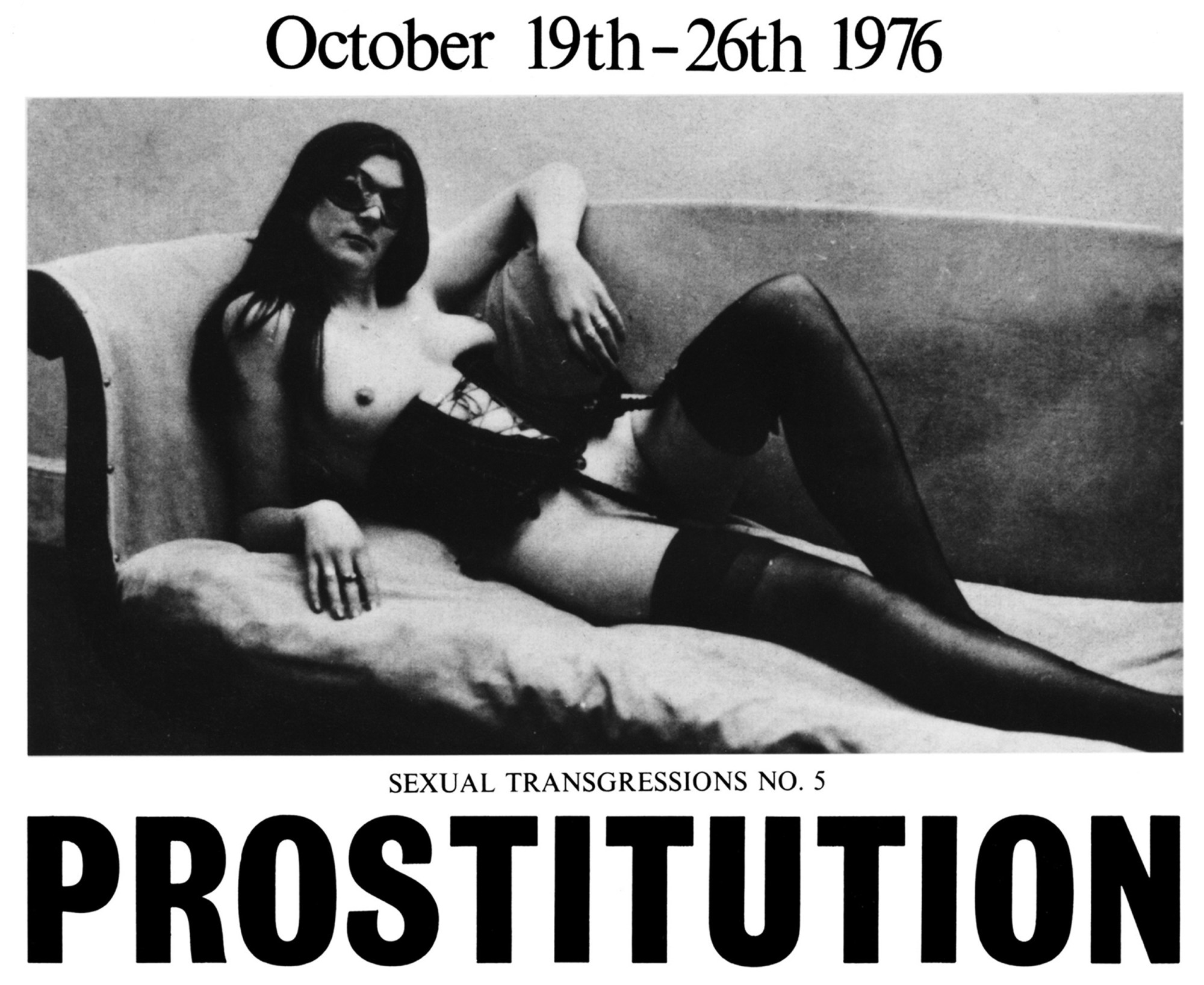

“Without risk, you don’t get anywhere, you don’t change things,” Cosey Fanni Tutti says, reflecting on the dramatic fallout from Prostitution, the 1976 art show that almost lost the ICA its funding and was even raked over in the House of Commons. It was her sex magazine works, framed clippings of her modeling work for real sex magazines and works that incorporated her used tampons, that caught the most flack in the press. The show functioned as a retrospective of COUM Transmissions, the radical performance art collective started in 1969 by Genesis P-Orridge, which Cosey — or ‘Cosmosis’ as Genesis had christened her — joined a year later. Marking both the end of COUM and the birth of pioneering industrial music project Throbbing Gristle, the artists couldn’t have wished for a more apoplectic review than that of Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn, who furiously labelled them “the wreckers of civilization.”

In 2017, COUM’s legacy is being celebrated as part of the Hull City of Culture program, but the artists didn’t always receive such a warm welcome in their hometown. Banned from most venues, they also had their street performances shut down by the police, part of a campaign of harassment that finally drove them out of town and to London in 1973. In Cosey’s recently-released autobiography, Art Sex Music, she paints a bracing picture of life on the estate she grew up on. Once, when another girl had beaten her up, she describes her dad marching her to the girl’s house wielding garden shears: “I knocked on the door, surprise-punched her when she answered, and screamed at her that if she ever touched me again I’d be back and have her with the garden shears,” she writes. “That’s Hull for you”.

Cosey’s dad wouldn’t let her go to art college, but that did nothing to dampen her ambitions. “I just felt that anyone could be what they wanted; in the world, anything was open to you,” she says, putting her drive and self-belief down to her dad treating her more like a boy (“to men, everything was available in the world,” she says), as well as the emergence of strong women like the Avengers on TV. “It sounds really benign, but it isn’t to a young girl, when she’s being pushed to be a housewife and get married and have children, and you see this woman that’s kicking the shit out of guys — you think, oh yeah, that’s more like me!” she laughs. “I didn’t think to myself, ‘I’m going to be an artist.’ I just thought, I’m going to do what I want to do, and I went out there and did it. And I’m still doing that now.”

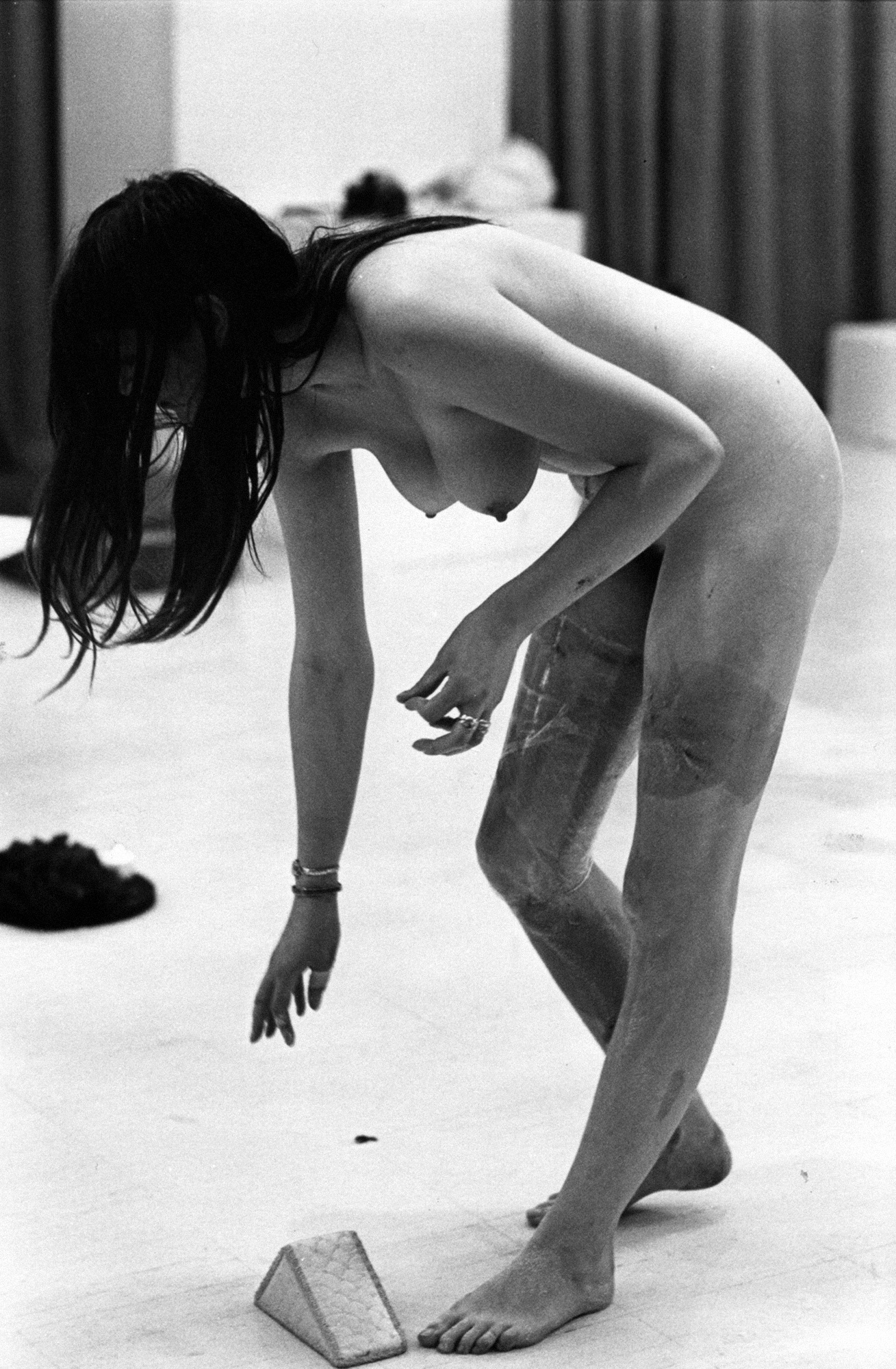

Cosey’s increasingly fraught relationship with her dad culminated in him kicking her out for being unemployed, and so in 1970 she moved in with Genesis at the Ho-Ho Funhouse, a Victorian warehouse where COUM members lived and made work. Though COUM’s public actions started out as tinsel-costumed street theatre, they became more extreme. An entry from Cosey’s diary recalls one performance: “I syringed my pussy, stitched my arm. We ended up all locked together in Gen’s piss, blood, and vomit.” The radical actions caused even fellow artists to walk out in disgust, but Cosey says they were never designed to shock. The work simply reflected their alternative and experimental lifestyle, which revolved around making art and following a path of self-discovery and sexual exploration. “We were so involved with personal discovery — and that included our sexual exploits. So, once we were doing the art actions, it was a continuum,” she says. “It came from real life into the space that we were working in.” The group described that continuum with the mantra ‘Life As Art. Art As Life’.

“COUM said: You live your life like it is a work,” Cosey explains. “If you’re creative every day, then that’s what your life becomes. It becomes more about that than a career in banking or something; it isn’t focused on anything else, so your life becomes about that artistic, creative drive”. When COUM transformed into the band Throbbing Gristle, following that principle led to the birth of industrial music. While we might now associate it with mechanical noise and factory spaces, Cosey explains that the ‘industrial’ epithet referred to being industrious, rather than any particular sound. “It was about the work ethic; the creative work ethic — being dedicated to the purpose,” she says.

With no formal training in either music or art, Cosey claims improvisation as her methodology, describing Throbbing Gristle’s process as being “like a live collage of sounds”. She points to the band’s best-known album, 20 Jazz Funk Greats, as evidence of their broad sonic influences, which ranged from from jazz to Martin Denny’s exotica. The album opens, as you might expect, with funky jazz, but the instruments soon become distorted, ushering in a darker sound. This dissonance is mirrored by the album cover, which shows the band looking wholesome, smiling, and surrounded by flowers cliffside at the notorious suicide spot Beachy Head.

Throbbing Gristle’s aesthetic and lyrics referenced sinister subjects, including Nazi death camps and the moors murders. Like their performance art, these topics weren’t used simply to shock, Cosey says, but as a way to highlight shocking events that they felt were being ignored or forgotten. “It’s that old saying: if you deny the past, you’re condemned to repeat it,” she explains. Cosey writes about finding a book of her father’s about the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Intuiting the trauma he suffered himself during the Second World War, she was left to wonder what had actually happened to him, as it wasn’t spoken about at home, and they didn’t learn about it in school. “When you know that something horrendous has gone on, but no one talks about it, it becomes a topic of… not fascination, but you want to know why? What happened?” she says. “We were aware of Nazi death camps, and also the moors murders were going on when I was a child. It’s not as if I’ve had no connection to these things,” she reasons.

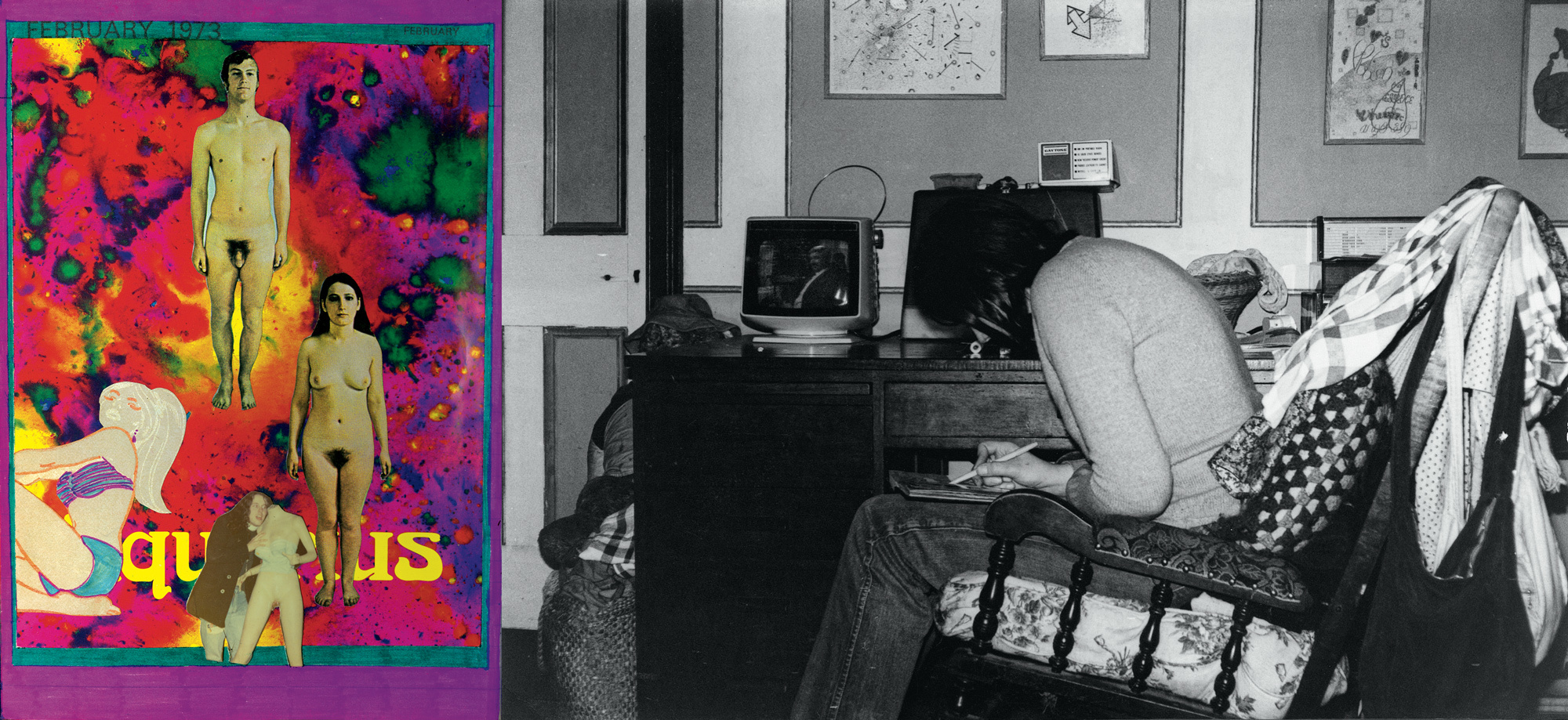

Cosey describes her move into sex work as having developed in a similarly organic and intuitive way. Initially, she was using cut-outs from sex magazines in her collages and mail art. Deciding it would be better to create the images herself, she got into photoshoots, beginning what she describes as a natural progression into stripping, and, eventually, hardcore films. “I don’t think a lot of people realize, but in the 70s, a lot of art students — and I suppose you’d call them ‘intellectuals’ — did a lot of work for sex magazines,” she says. Magazines like Curious (the first she appeared in) were a hybrid of sex and music, featuring pornographic images and articles on David Bowie. Cosey got into stripping through a friend who was both a stripper and a writer for Artforum.

As you might imagine, working in the sex industry in the 70s exposed Cosey to an even greater level of sexism and threat of sexual violence than usual. What is perhaps more disturbing about her autobiography is that the descriptions of life with Genesis are arguably worse. Depicting a manipulative and abusive relationship, Cosey alleges psychological and physical violence that includes being kicked, strangled, and, at one point, having a breeze block thrown at her from a height (it just missed her head, she writes). Despite the tsunami of sexism documented in the book — from judgemental family doctors to ‘friends’ attempting to have sex with her while she slept, the trials of living with Genesis, and sleazy photographers at work — Cosey is clear that she did not identify as a feminist. Sh writes that the movement simply offered another set of rules for women to live by. She does, however, accept readings of her work as feminist now. “In retrospect, I think they are,” she says. “Whether I acknowledged the fact that I was a feminist at the time, I was obviously acting outside what I ‘should’ have been”.

The risks Cosey took paid off artistically, but they weren’t without consequence. The press coverage of the ICA Prostitution show severed her relationship with her mother for life. But they have fueled a creative career that has seen her innovate across both music and art. Just last month, the Throbbing Gristle archive became available on streaming services for the first time, but that’s really only the beginning of the story. After Throbbing Gristle, Cosey and her partner Chris Carter broke away to make influential electronic music as Chris & Cosey, and later as Carter Tutti, receiving huge critical acclaim for their recent collaborations with Nik Colk Void of Factory Floor (as Carter Tutti Void).

Though the book is motivated in part to tell Cosey’s side of the story, after decades of alternate versions and wild rumors it is more so a document of a pioneering artist and musician and her experiences as a daughter, friend, lover, and mother. Having lived with the mantra “My life is my art, my art is my life” for almost 50 years, it’s clear that Cosey has become a radical model for a creative life well lived.

Credits

Text Charlotte Gush