“To call Irving Penn a fashion photographer is to misjudge one of the most complex and intriguing artists of the latter half of this century,” art critic and historian Andy Grundberg wrote in The New York Times in 1991. Sure, Penn contributed to Vogue for more than six decades, and his austere portraits of Parisian couture and the cultural elite—Truman Capote, Picasso and Colette, among others—are unforgettable. But his personal projects, from his 1938 photos of storefronts and street signs to his 2007 series of ceramic vessels, are works of art.

For these series, Penn approached often-ignored people and objects—from dockworkers and mailmen to sidewalk gum and cigarettes—just as he did Didion or Dalí. Each of his photos, no matter the subject, were meticulously arranged and bathed in a careful balance of light and shadow. When Penn started experimenting with platinum printing in the mid-1960s—a previously obsolete and time-consuming technique that required brushing a metallic solution onto paper by hand—he achieved even richer tones and textures. The result, and the process, was much more like a painting than a common print. “Penn was Ingres with a Leica,” Adam Gopnik described in The New Yorker in 2009, “all ravishing edges and perfect composition and a quality of deep color that was the envy of every other photographer.”

To commemorate the life and work of Penn—who is still the envy of everyone 100 years after his birth—the Metropolitan Museum of Art will host Irving Penn: Centennial from today until the end of July, when it will begin traveling. In advance of the retrospective, which is the most comprehensive of the artist’s work to date, we discuss five of his less fashionable topics, each of which helped propel Penn into the realm of high art.

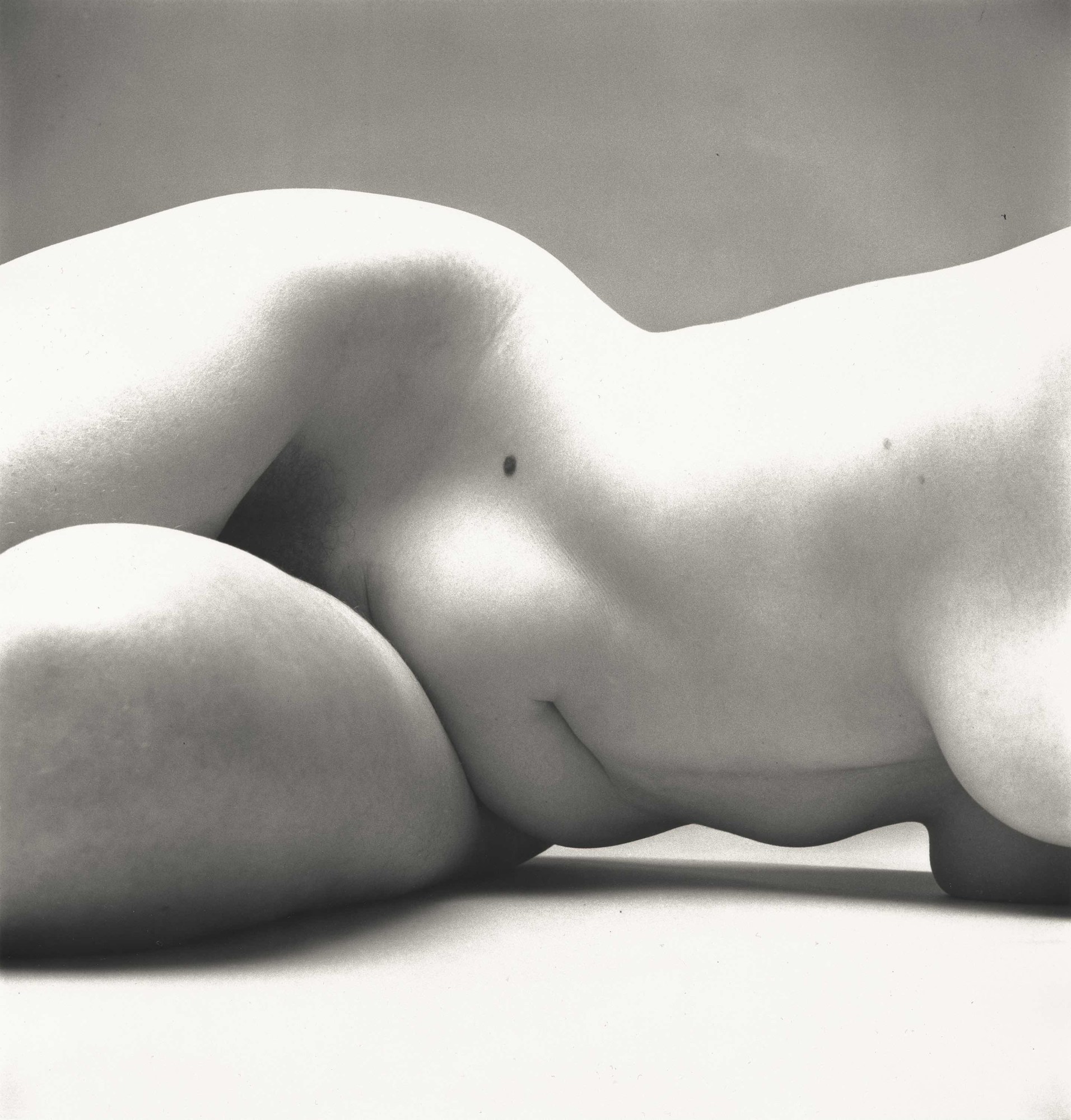

Earthly Bodies

Far ahead of his time, and of fashion, Penn started to photograph real women’s bodies in the late 1940s. “One day in the winter of 1947, Irving Penn, a promising young photographer, walked away from a dressing room full of slender, beautiful models and boarded a plane for Haiti,” Maria Morris Hambourg, the curator of the current Met show, wrote in ARTnews in 2002. “He was not unhappy with his job at Vogue, but he felt the need for some ‘real women in real circumstances,’ as opposed to those ‘skinny girls with self-starved looks.'” When he returned from Haiti, he booked Rubenesque models to pose for him in his studio, and photographed them from the neck down. In his gaze, the women’s rounded stomachs and sagging breasts resembled the ancient Venus of Willendorf figurine, and became modern symbols of fertility and beauty. Alexander Liberman, the director of Vogue at the time, did not approve, but in the fall of 1980, 76 of these nudes were exhibited at the Marlborough Gallery in New York.

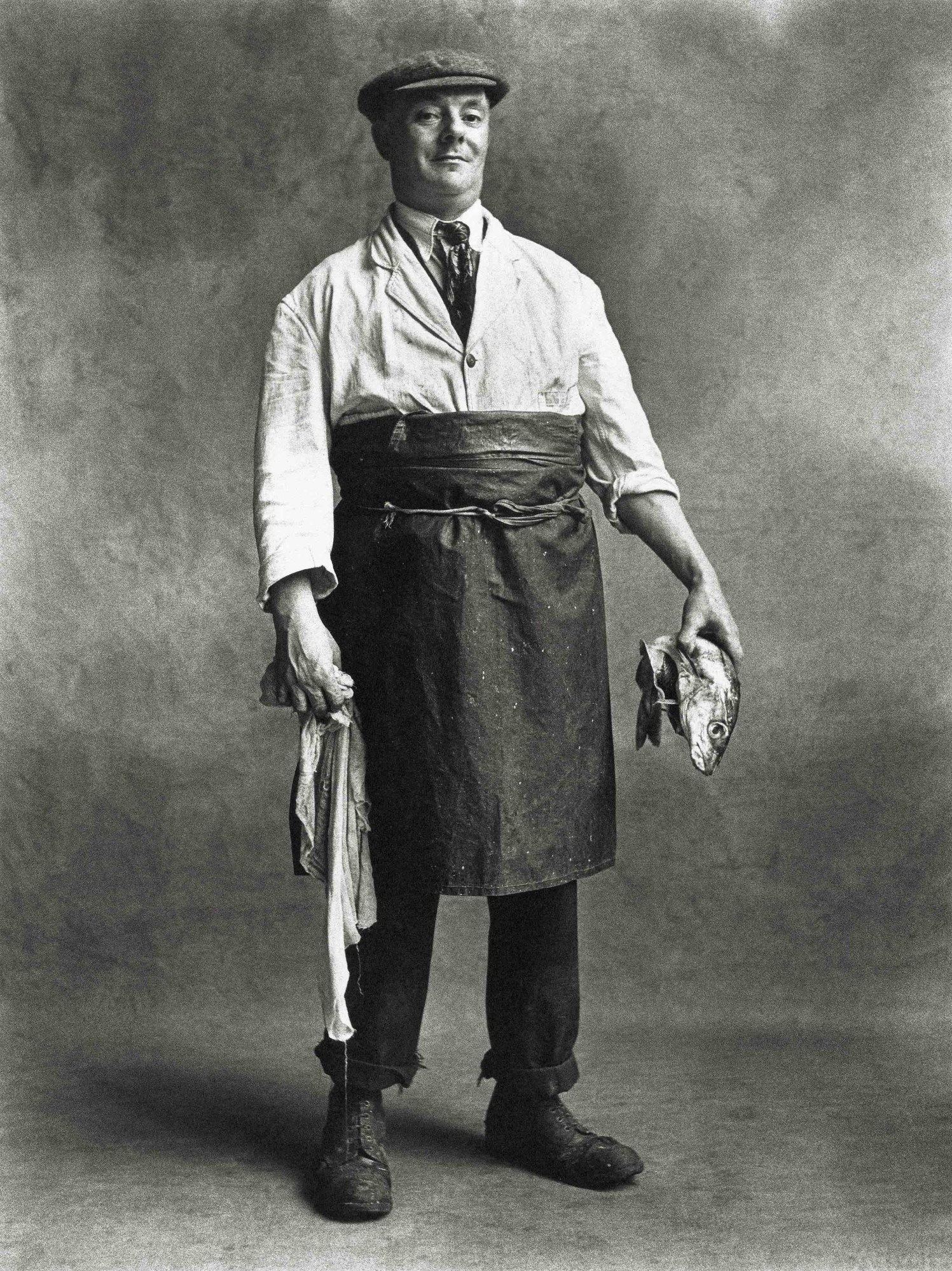

Small Trades

While working in New York, London and Paris for Vogue, Penn photographed working-class men and women between 1950 and 1951. He shot butchers, fishmongers, chimneysweeps and cobblers, among others, in order to capture images of the skilled tradespeople who were increasingly disappearing from the urban landscape. The chamois seller he photographed, for example, a rotund man blanketed in goatskins, was one of just two chamois sellers left in London at that time. Penn photographed the tradespeople in their soiled work clothes, carrying their tools, against the same cloudy backdrop he used for many of his celebrity portraits. “Rather than picture [his subjects] where they worked, Penn brought them into his studio to pose like models against a sooty gray paper background,” the San Francisco Chronicle described. “The smoky light of his black-and-white prints makes them look like living sculpture, carved into individuality by their life experiences and their times.” Penn returned to the Small Trades series throughout his career, and it became his most extensive body of work.

Cigarettes

In 1972, Penn produced a series of platinum prints of smoked-down cigarette butts. He shot the discarded cigarettes in much the same way that he shot high-end products—each cigarette, and its ashes, was perfectly composed against a white background. “The elegance of these pictures is similar to that which we find in his pictures for Chanel’s cologne for men, for Clinique’s lipstick or in brightly colored still lifes of flowers,” Michiko Kasahara wrote in an essay in Irving Penn Photographs (1997). “Whether the subject be cigarette butts or high fashion, they find equivalence through the elegance of Penn’s technique.” Although the beauty of these images is incontestable, Penn himself was strongly against smoking, and these images contain that sentiment. In 1975, Cigarettes was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art. “That single exhibition,” Francis Hodgson wrote in the Financial Times in 2012, “overcame the strong prejudice against ‘commercial’ photographers being welcomed in the museum.”

Street Material

The success of Cigarettes led Penn to photograph other detritus he found on the street, such as wads of chewed gum and flattened paper cups. “I can get obsessed by anything if I look at it long enough,” he once said. “That’s the curse of being a photographer.” Through his lens, street trash, which most people turn their eyes away from, became something fascinating, even iconic. Street Material was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1977, and this exhibition, combined with the earlier Cigarettes, confirmed that Penn was more than a fashion photographer—he was an artist. “[These works] were—significantly—not shown in the department of Prints & Photographs,” Hodgson wrote. “Instead they were the first photographs ever shown by Henry Geldzahler in his Department of Twentieth Century Art. These pieces, in other words, represent the blood royal of contemporary art photography.”

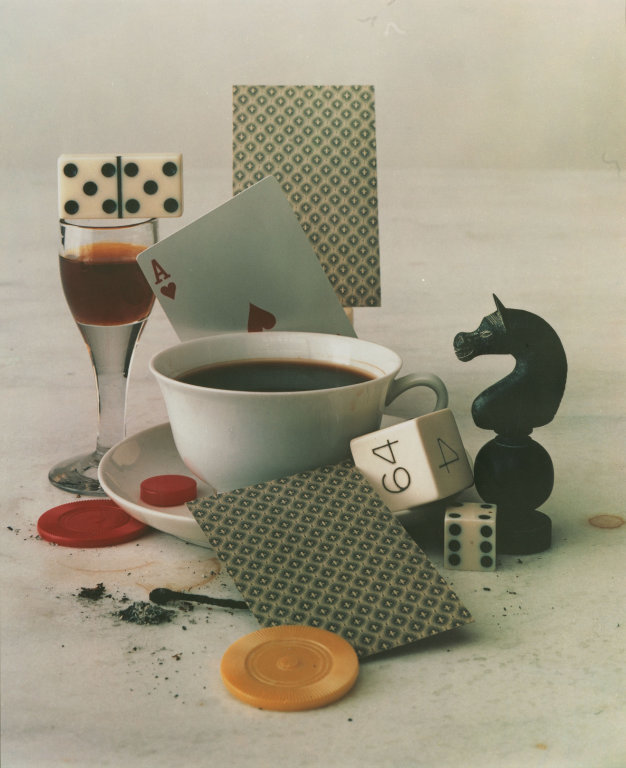

Still Lifes

Penn’s personal work was often a direct reaction to his fashion photography. Liberman once told him that the editors at Vogue didn’t like his photographs because they “burn on the page.” “I began to understand what they wanted of me,” Penn said, “was a nice, sweet, clean-looking image of a lovely young woman.” From 1979 to 1980, Penn photographed still lifes of found materials—pieces of glass and metal arranged with bones or even a human skull. “When the prints were shown,” Penn said, “I admit I was surprised at the hostility they provoked.” Of course, he went on to produce many unusual and artistic still lifes for Vogue and they became among his most iconic published photographs. In 1990, critic Richard Woodward wrote, “The steely unity of Irving Penn’s career, the severity and constructed rigor of his work can best be appreciated when he seems to break away from the dictates of fashion for magazines,” he wrote. “Only then is it clear how everything he photographs—or, at least, prints —is the product of a remarkably undivided conscience. There are no breaks; only different subjects.”

Credits

Text Zio Baritaux

Photography Irving Penn (American, 1917-2009), credits, top to bottom:

1. Glove and Shoe, New York, 1947

Gelatin silver print

9 5⁄8 × 7 3⁄4 in. (24.4 × 19.7 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

© Condé Nast

2. Nude No. 72, New York, 1949–50

Gelatin silver print

15 5⁄8 × 14 3⁄4 in. (39.7 × 37.5 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gift of the artist, 2002

© The Irving Penn Foundation

3. Fishmonger, London, 1950

Platinum-palladium print, 1976

19 3⁄4 × 14 7⁄8 in. (50.2 × 37.8 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Purchase, The Lauder Foundation and The Irving Penn Foundation Gifts, 2014

© Condé Nast

4. Cigarette No. 37, New York, 1972

Platinum-palladium print, 1975

23 1⁄2 × 17 3⁄8 in. (59.7 × 44.1 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

© The Irving Penn Foundation

5. Deli Package, New York, 1975

Platinum-palladium print, 1976

15 7⁄8 × 20 3⁄4 in. (40.3 × 52.7 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

© The Irving Penn Foundation

6. After-Dinner Games, New York, 1947

Dye transfer print, 1985

22 1⁄4 × 18 1⁄8 in. (56.5 × 46 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

© Condé Nast