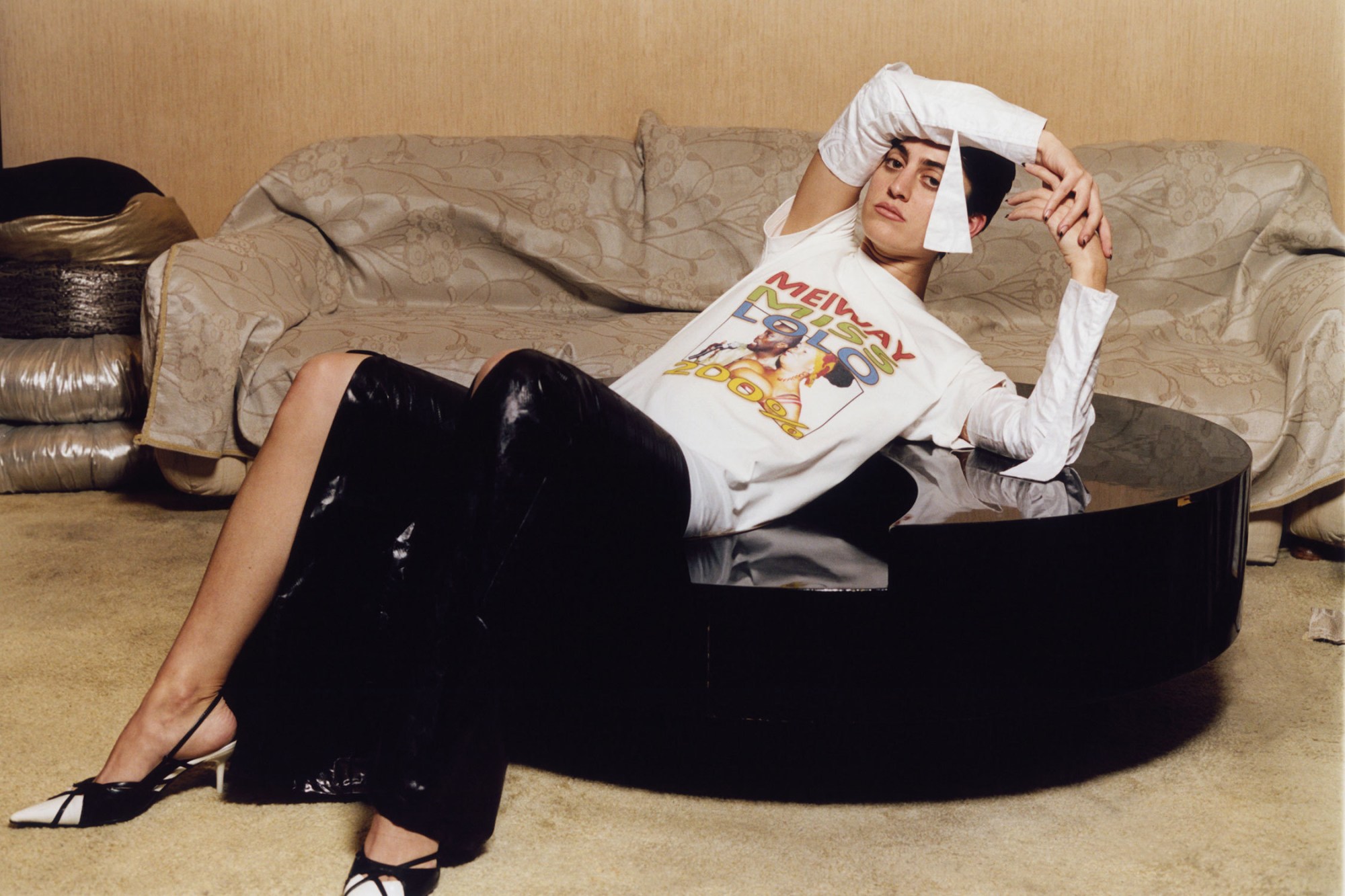

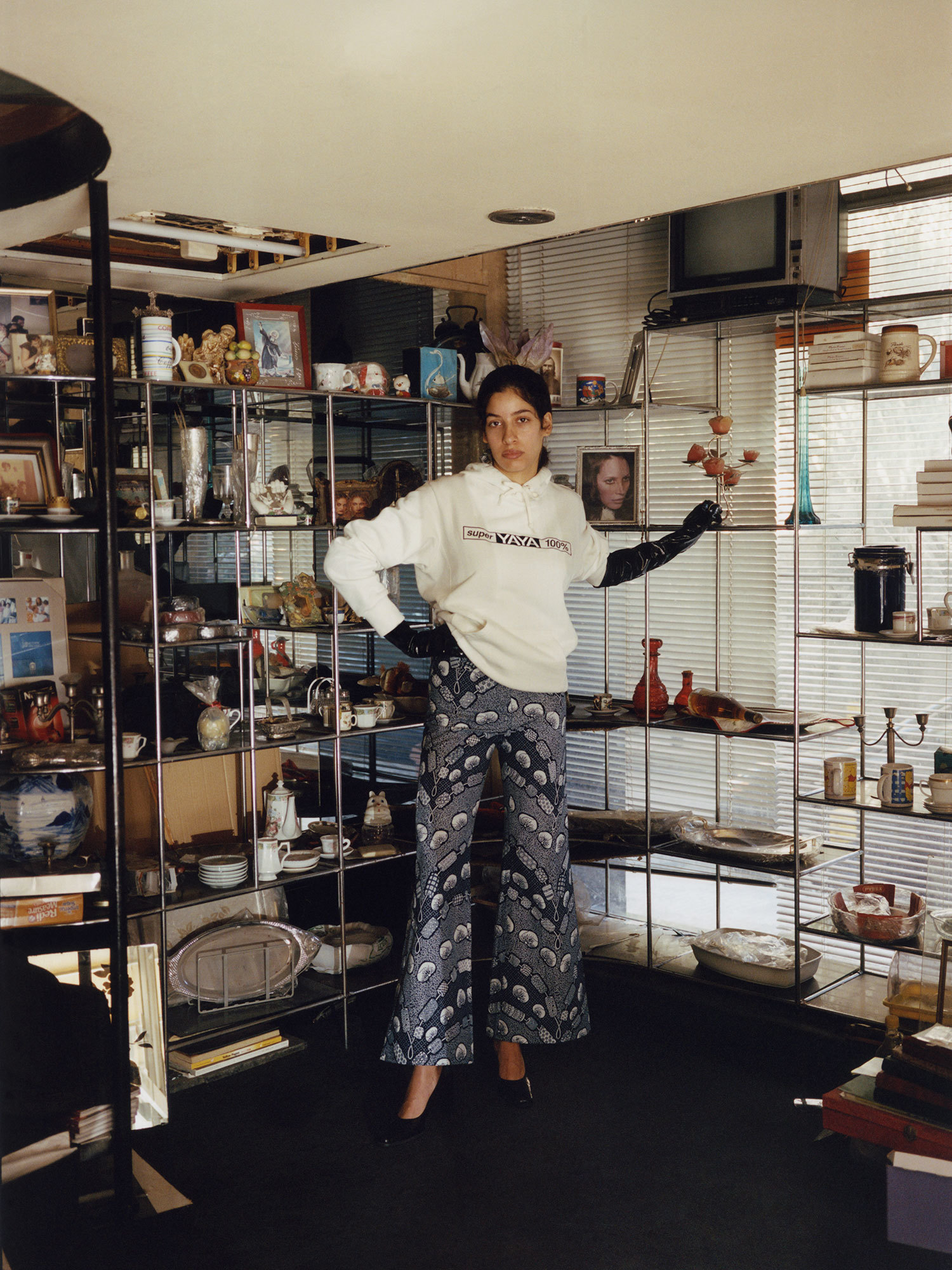

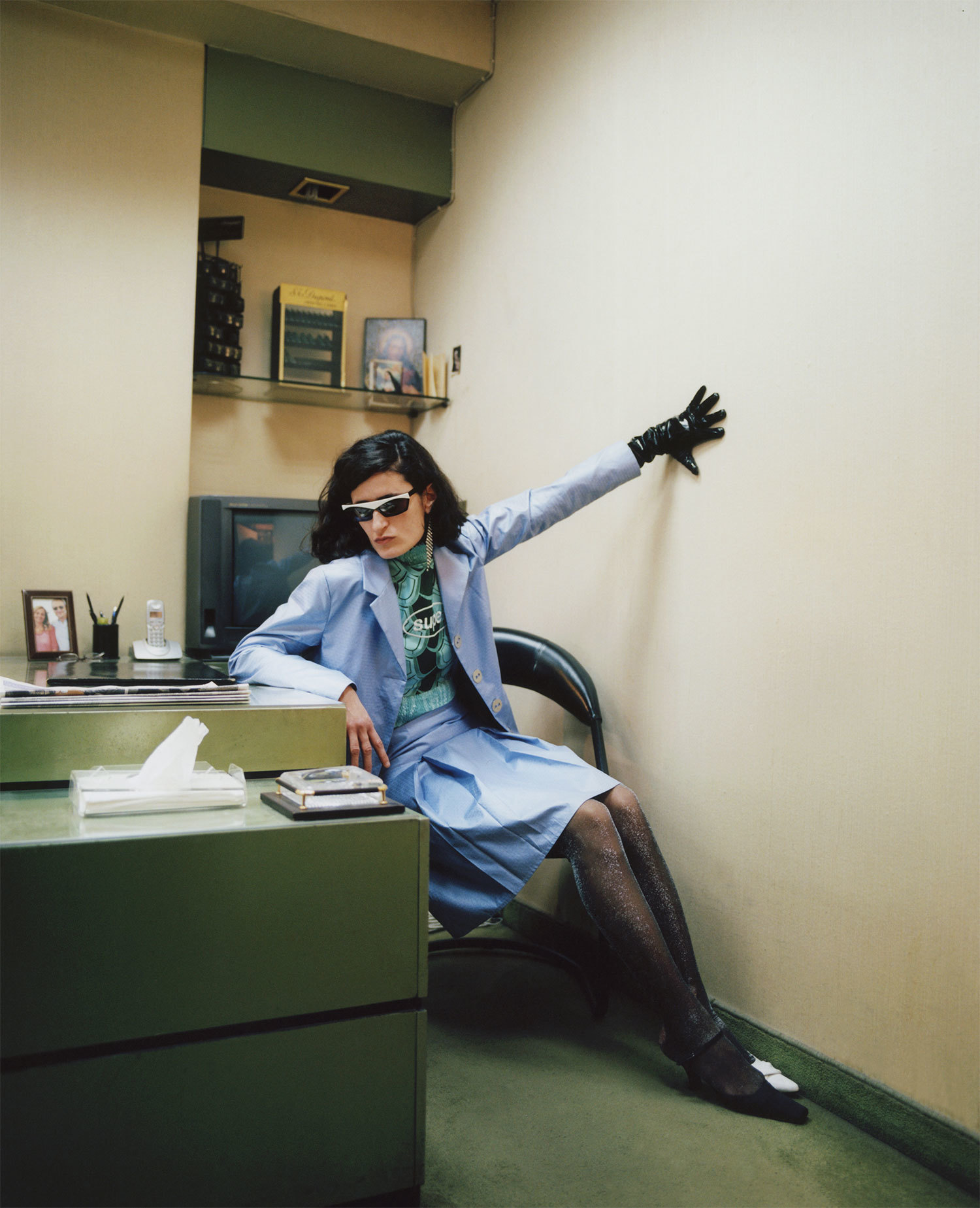

Born and raised in Abidjan, young Lebanese artist Rym Beydoun was never going to lack a unique point of view. The Central Saint Martins graduate set up her label SuperYAYA last year, inspired by the raw and innovative design she discovered during her placement year back home.

Now based between Lebanon and Cote d’Ivoire, Rym looks to redefine Afrofuturism in fashion, stepping away from the exoticizing gaze of the West to offer a modern and authentic image of her home continent. 1 Granary meets Rym, the creative force behind the new brand, to discover its roots.

You seem to have a very clear narrative and authenticity about your work. Has it always been this way? Can you give us an insight into your background?

I was born in Abidjan but my family moved to Dakar in the early 90s, making me a fourth-generation Lebanese West African. I lived in Cote d’Ivoire until my family and I had to leave for Beirut to flee a coup in Cote d’Ivoire in 1999. Although I am originally Lebanese, I feel deeply Ivorian. I was around so many different types of people at an early age — it shaped my worldview.

Do you think these diverse cultural associations explain your desire to develop a connection between people and places in your work?

Yes, especially when Lebanese people are not expected to be so prominently present in places like Cote d’Ivoire or Senegal. I like unexpected stories and wanted to portray different cultures that were interacting using the brand. I was hoping to build a bridge between Beirut and Abidjan, to reconcile my origins and identity. This is why we shot the fall/winter 17 lookbook with Joyce NG and Makram Bitar in Beirut. It started feeling important to shoot in Lebanon and not only in Cote d’Ivoire. However, the main thing I try to translate through SuperYAYA is undeniably an African modernism that is so often forgotten.

You have a very open-minded approach to fashion. Is this a conscious decision to reject fashion clichés?

Yes. To me, the brand is about everything that inspired me to create the visuals — from the music that drove me to start the label, to the motocross courses I used to take. I would like the brand to remain 100% flexible. The initial idea was to eventually develop it into something like a supermarket. If I feel like creating SuperYAYA tires or bikes, I want to be able to do so. It’s not just about the fashion, or about the clothes. It’s more than that.

What got you back on the fashion carousel?

Once I got into the fashion course, there was no way back — it felt challenging, and although I didn’t like it, I tried to work out a way around it. I was going to drop out, but then I found the best tutor to guide me, and I left London for my placement year. I went back to Abidjan on my year off. I felt like I rediscovered myself being back there in this familiar place, but at a different age and stage in my life. I had a newfound appreciation for everything. Everything inspired me and I started understanding how to use fashion as a medium to translate my ideas. I felt there was no real portrait of where I came from, and I became really fascinated in being able to paint my vision of Cote d’Ivoire through the brand in eradicating fabricated and simple views.

Where did you work while you were in Cote d’Ivoire? You seem to have pushed beyond the usual experience of your peers.

I worked and interned in Abidjan first with a street tailor in the city. I then worked with Laurence Chauvin Buthaud, who had just started his label Laurence Airline; with Miguel, who made tailored suits for government ministers; and at the UNIWAX factory’s print studio, where we created wax prints. I also traveled around Central Africa (Congo Brazzaville, Gabon, Central African Republic, Sao Tome) and conducted visual research, which exposed me to fundamental differences between the African way of working and the Western one. In Abidjan, the fabrics are the trends, not the clothes themselves. New prints are sold every day at the market and people buy their fabric, then go and make their own clothing. The individual is the designer. This felt so raw and creative. It was at this moment that my mind started thinking of how I could take this alternative idea of design outside of the country.

So, this is when the idea for Super YAYA was conceived?

Exactly. I then thought of creating a platform that would allow the buyer to be engaged in the design. The e-commerce site would offer a selection of fabrics and styles, the buyer would choose what they wanted and I would make and ship. There was no stock; the customer would just see design and textile on the screen.

So how did the ready-to-wear concept come around?

Demands increased and stockists started getting interested, so I had to quickly develop a different strategy. I created two original YAYA t-shirts that I sold as I was developing a complete unisex collection that I would show on-schedule.

Why did you wait until 2016 to launch SuperYAYA, if the idea had been brewing since your year off?

It was very important for me to work thoroughly on branding and what I wanted SuperYAYA to look like. The vision had to be very precise. I knew some things could only be expressed and translated visually — so I made sure the visuals were strong enough and created images more than I created clothes. It’s only now that I can actually focus on designing clothing. I wanted the purpose and story to be as accurate as possible and I thought it needed time to mature naturally and genuinely.

SuperYAYA has coincidentally emerged at a time when fashion is in need of culturally aware brands. What are your thoughts on your place within this discussion?

Cultural diversity is on-trend, race is on-trend, and skin color is on-trend. I find it really annoying that people can make a thing out of nature and reality. Fashion can really make anything fashionable and I find it difficult to avoid. I feel like it’s a mix of fetishism and exoticism. This is why everything is fake and forced. It is natural for designers and artists to look for inspiration outside their immediate spheres, but objectification and appropriation of cultures are always very apparent and unattractive. I don’t think I would be highlighting an issue or a context if I did not feel part of it or didn’t completely relate to it.

Your unusual upbringing has meant that you seem to instinctively negotiate cultural differences. Was it always your intention to create a link between different worlds without portraying them in a stereotypical and easily digestible manner?

Absolutely. For example, just because I’m based in Abidjan and some of the fabrics I use are fabrics printed in the Cote d’Ivoire does not mean all my models will be black — not everyone in Cote d’Ivoire is black; I myself am not black. I want to erase those assumptions and stereotypes through the brand. It is more than a question of just black and white in Abidjan or Dakar. Lebanese-Ivorian and Senegalese-Ivorian relationships are different. I often get people saying, ‘but you are white.’ But in Abidjan, ‘white’ stands for French or European. This is why you would hear locals ask, ‘Are you white or are you Lebanese?’

Credits

Text Naomi Barlin

Photography Joyce NG

Styling Makram Bitar

Photography assistance Jimmy Dabbagh

Thanks to 1 Granary