Last week, the internet collectively bowed down at the sight of Michelle Obama’s natural hair. Gone were the blow-out bobs we’d grown accustomed to seeing for nearly a decade. In their place was a soft, textured ponytail tied casually at the neck.

For the first time ever, the Michelle Obama on display was a black woman unburdened by the respectability politics of Washington, D.C. At least, that’s what many people around the internet projected. The visual was a much-needed breath of fresh air after defending congresswoman Maxine Waters against anchor Bill O’Reilly’s foolish “James Brown wig” comments. This was our victory, and the former FLOTUS our hero. For many black women in the west, hair is, without question, political.

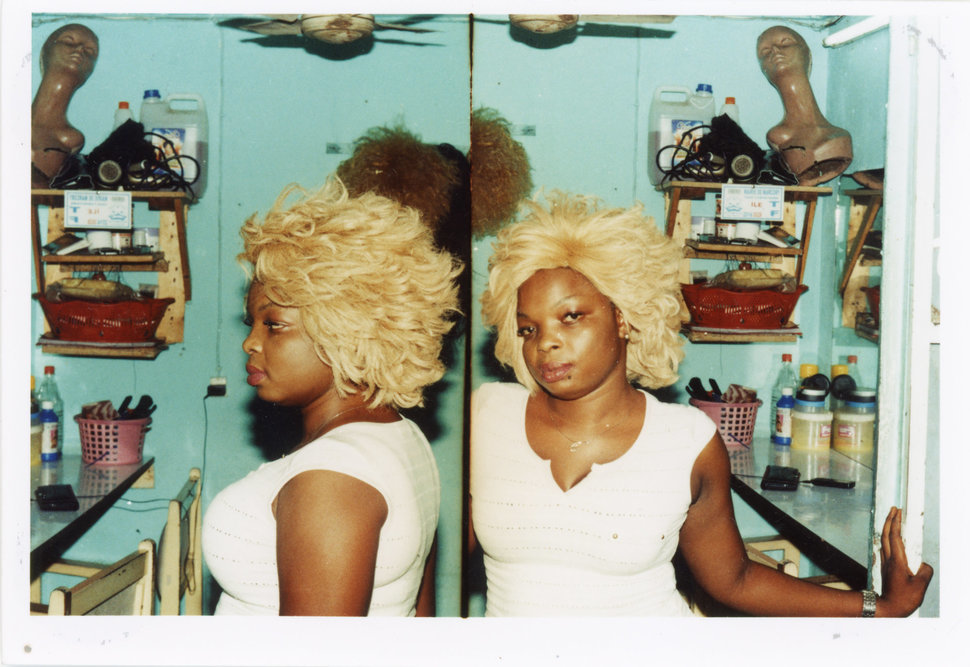

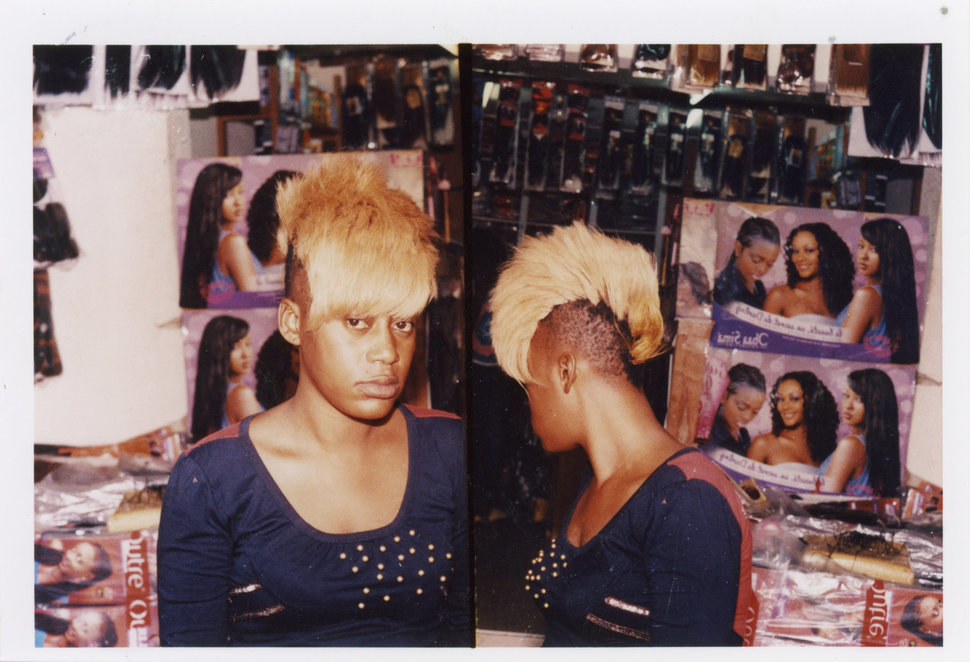

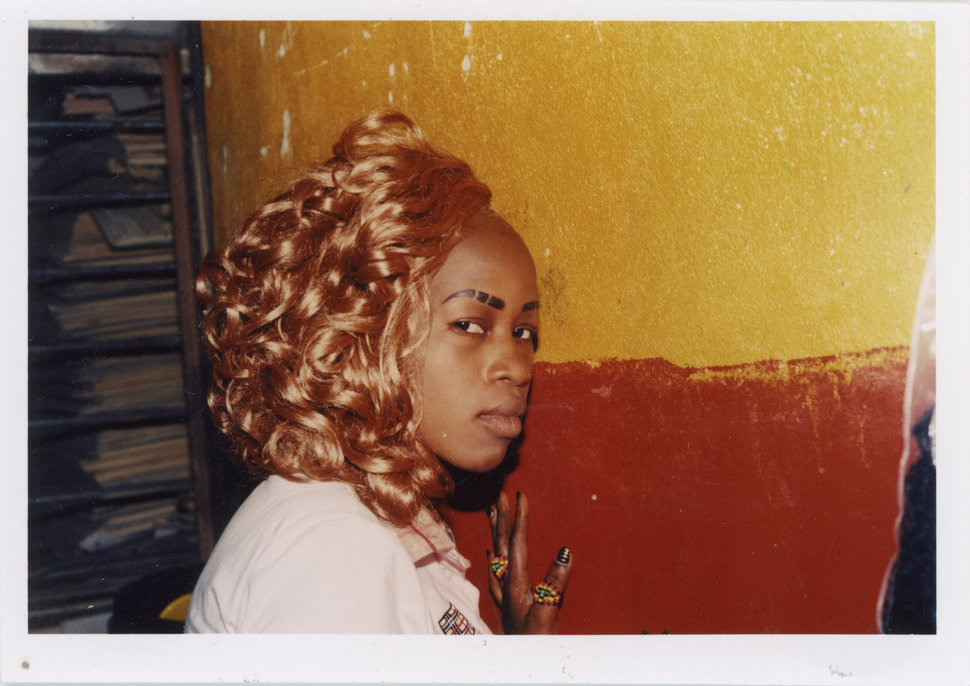

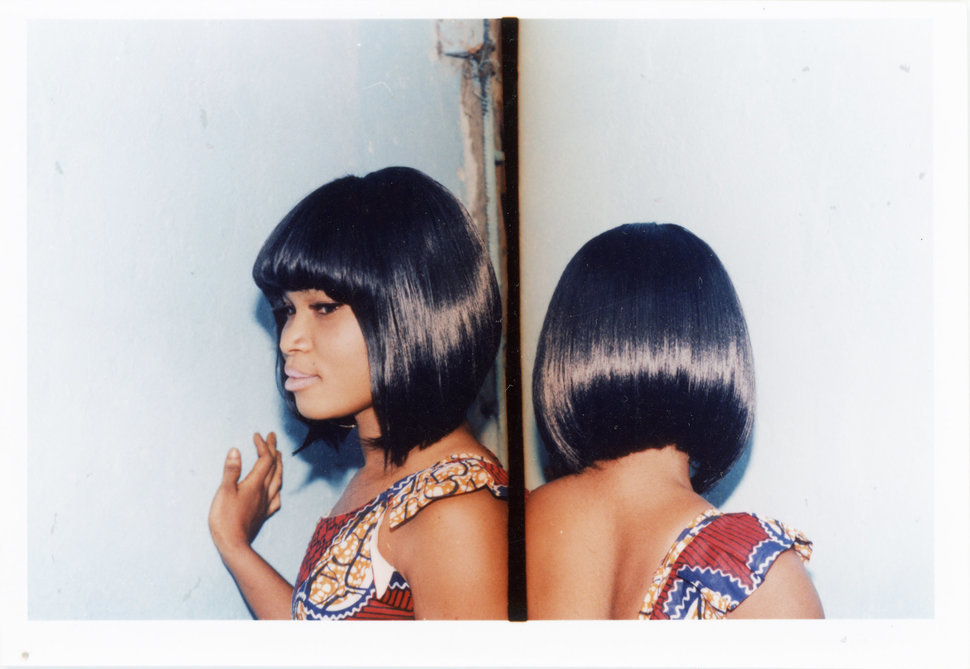

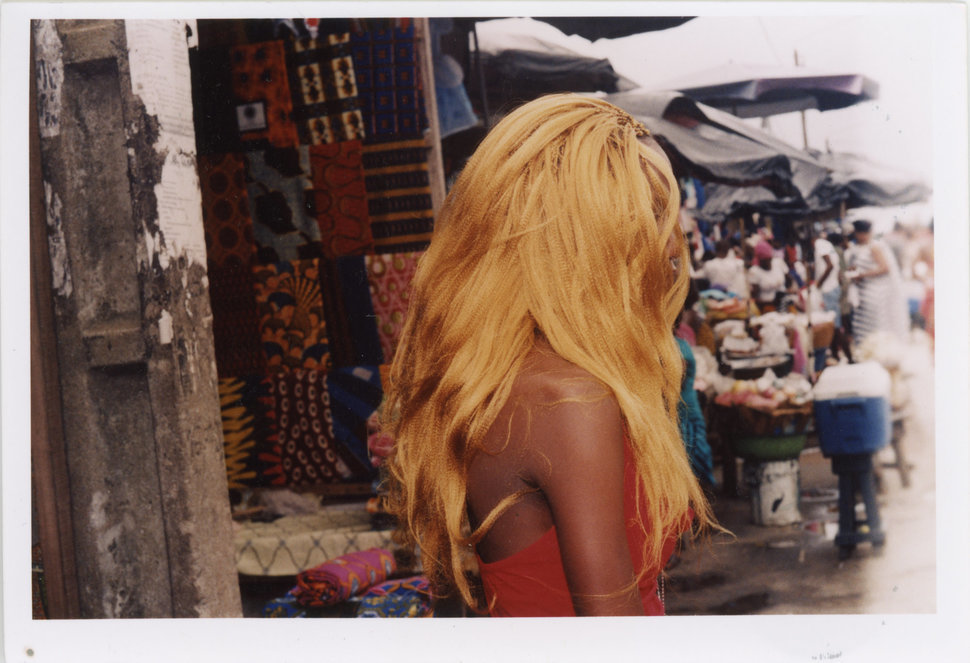

Though, according to Canadian-Haitian photographer Émilie Régnier, our beauty choices aren’t always so explicitly driven by personal politics. According to the female subjects she photographed in her forthcoming exhibition From Mobutu to Beyoncé at the Bronx Documentary Center, women just want to have fun. In Régnier’s series “Hair,” the 33-year-old captured women in the beauty salons of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. The result is a bold display of women doing, well, whatever the hell they want with their hair. And for Régnier, seeing these women peacock for the camera was more than just work, it was an education.

What were the main differences between the way women in Abidjan view their hair and the way black women in the U.S. do?

In Abidjan, the way women do their hair is [a reflection] of the society. Though I’ve never made work about this topic in the U.S or in Europe, in my opinion, it’s the same phenomenon in those places. We are all part of a social/economical/cultural group that we want to fit into and our aesthetic choices [are] guided by that desire.

What did you learn from shooting these women?

That we all look at beauty through a cultural prism. Even if the biggest influence on beauty comes from Western society, people still decode that information through their own prism. The most important part [of our individual aesthetic processes] is how we re-appropriate and re-invent style. The women I photographed in Abidjan had a unique take on what they saw on television, and they were incomparably creative. They expressed a certain modernity. Beyoncé and Rihanna were the figures of reference for nearly all of the women in my series, and they somehow reflect our mixed society. They allow us to see different aspects of beauty.

How did you choose your subjects? Was there a particular trait you were drawn to?

I photographed over 100 women during a two-month period in 2014. I was often drawn to blonde women. I wanted to understand why do so many African women want to be blonde, and I guess I was also trying to understand my own relation to my hair. I colored my hair blonde when I was a teenager. I learned from this experience that despite any intellectual position about neocolonialism and alienation that we may have, for the women I photographed, there was no doubt that they were beautiful and to me this is what matters.

What was your relationship with beauty shops and hair salons growing up? Do you have any particularly strong memories?

Oh my god… you have no idea. The first part of my childhood was spent in Gabon so I was surrounded by kids with hair similar to mine. Later, my mom and I moved to Canada, to the small town where she was from. I think there were like two black kids in the school. I had an afro and the kids would call me Einstein and wanted to touch my hair all the time. This is when I got exposed to North American culture and began to feel something was different about my hair. After that, I spent years trying to fix my rebel hair, to try to fit into some kind of Western aesthetic in order to be part of a group. I colored my hair blonde, I relaxed it. My dream back then was to have my hair blow in the wind. In the 1990s and early 2000s, there were very few role models for a young black teenager in Canada.

I had a conversation with close girlfriends recently about the scars we received from irons and relaxers as children. Do you have scars from any hair experiences as a child?

I did have burns after relaxers. They were so painful and you hair would smell for weeks afterwards.

We often speak of the West’s influence on parts of Africa, but in what ways have you observed Africa’s influence on the West?

In fashion and in the arts, Africa’s influence has been felt in the West for while. Picasso was already inspired by Africa in the early 20th century. But now we are more quick to recognize where the influences come from and a lot of fashion designers from Africa are getting their place under the sun in New York, London, and Paris.

In your artist’s statement, you say: “Once a place becomes familiar, you don’t see everything you used to.” As an artist, how do you continue to see the world with new eyes?

I spend lots of time staring at my ceiling wondering about that. When I work, I try to move away from my own perception of beauty and life to get immersed in other people’s perceptions. I try to pay special attention to detail. It is the challenging part of the work. On the other hand, I also feel that it’s only when you get accustomed to something that you dig deeper into it.

Tell me about your relationship with your own hair and appearance. Has your perception of yourself changed with age and traveling?

Hell yes. I finally reached a point where I didn’t want to be blonde anymore. I managed to accept my hair, but it took time. I read Juliette Sméralda, a French-Caribbean sociologist, and in her book about hair, she points out that as young girls, women in the Antilles just had white Barbies with silky blonde hair to play with. This contributes to the alienation of being a black woman with natural hair. It starts when you are a little girl and are exposed to the domination of white cultures. Though, in recent years there have been many more dolls and Barbies with afro hair. I hope it helps younger generations to love what nature gave them and maybe avoid the pain of burns and scars from relaxers.

“From Mobutu to Beyoncé” by Émilie Régnier is on view at the Bronx Documentary Center from April 15 through June 4.

Credits

Text Marquita Harris