When Arthur Jafa’s film Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death opened at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in Harlem last November, The New Yorker deemed it “crucial” and “required viewing.” According to Jafa, the accolades were taken as instruction. Recently, someone confessed to the artist they came across a pirated version. Jafa is a celebrated cinematographer whose credits include Daughters of the Dust, Crooklyn, Eyes Wide Shut, and Solange’s “Cranes in the Sky,” and much of his sensuous, arresting work was created for the big screen. So I assumed he’d be furious — not exactly. “If it’s not being pirated, it can’t have any relevance whatsoever,” he says with a laugh.

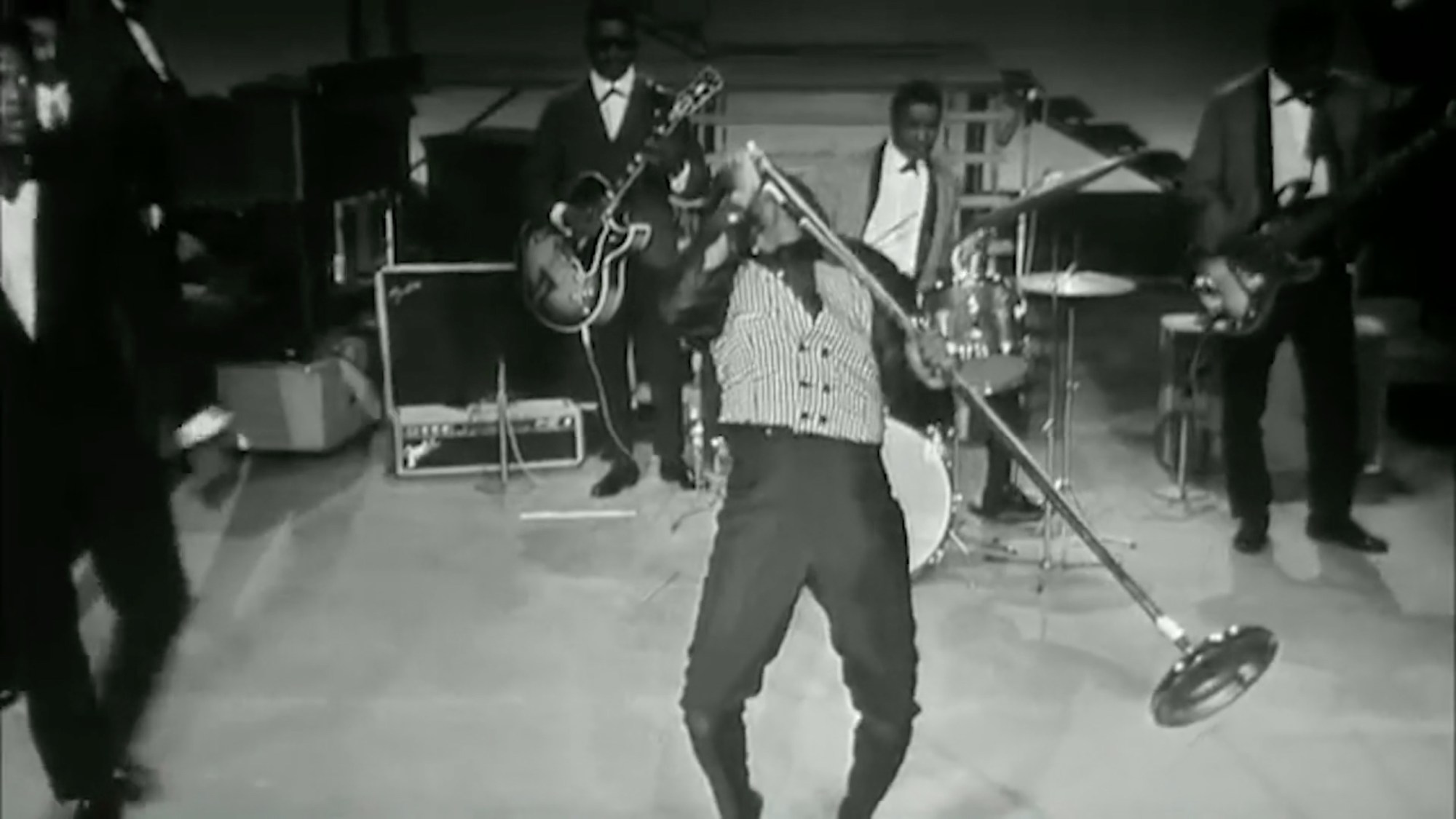

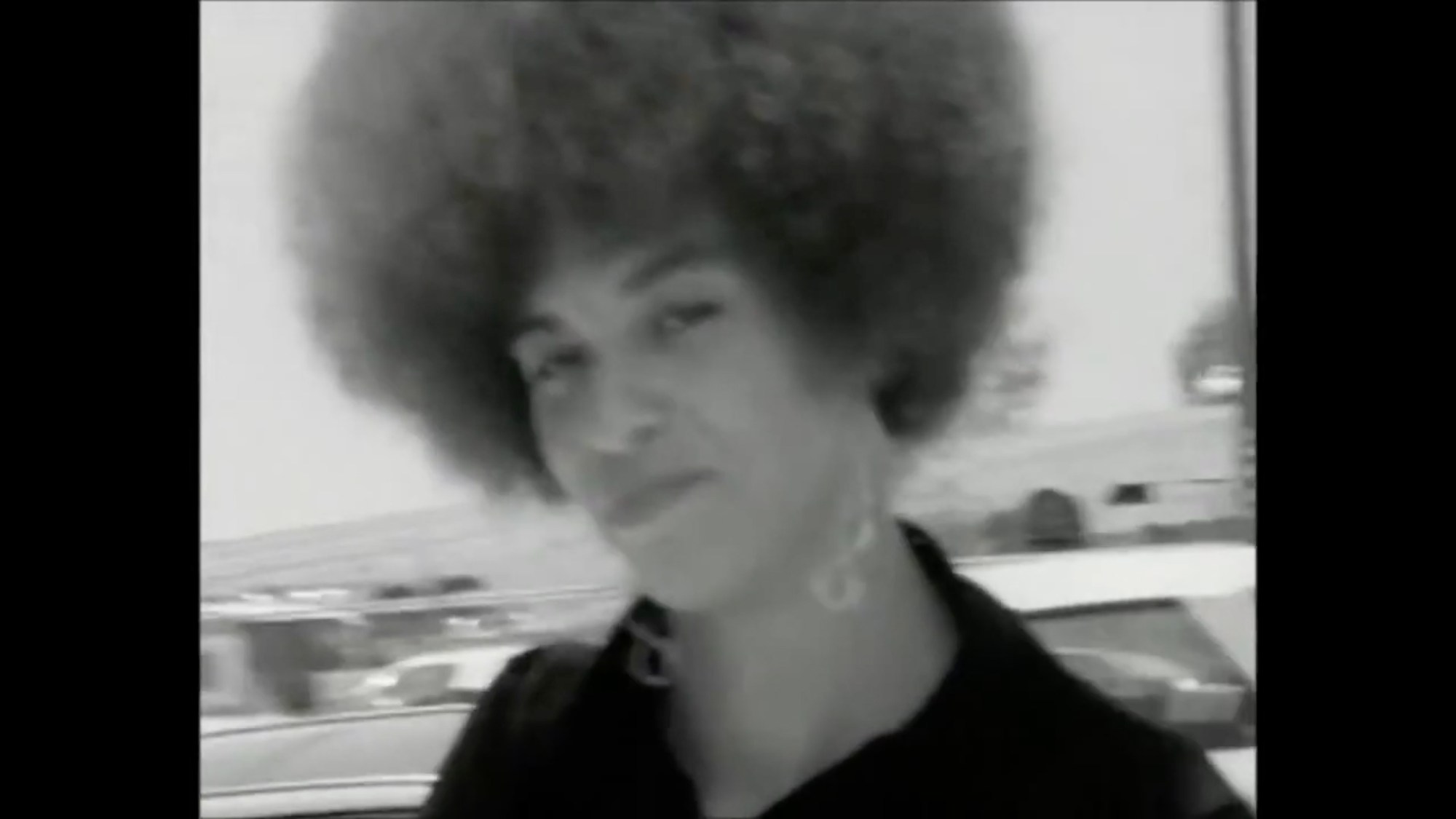

Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death — an amalgamation of found footage set to Kanye West’s gospel epic “Ultra Light Beam” — is a lot of things. Chief among them: relevant. Jafa has often stated that his aim is to “make cinema with the power, beauty, and alienation of black music.” This piece achieves it in seven minutes. Jafa explores African-American identity by colliding imagery from news coverage, music videos, police dashcams, home movies, iPhone videos of protests, YouTube, documentaries, and Hollywood classics.

The film’s title is itself a multi-part reference. It alludes to disco-funk track “Love Is The Message” by MSFB, a collective of more than 30 studio musicians based in Philadelphia. The song is an up-tempo 70s club cut that was often spun by the legendary DJ Larry Levan. Jafa’s title also nods to “Love Is the Plan and the Plan Is Death,” a short story by speculative fiction author James Tiptree, otherwise known as Alice “Raccoona” Bradley Sheldon.

The dual homage is fitting. Love Is the Message shows black bodies in ecstasy, choreographed precision, ecclesiastical rapture, athletic exertion, anguish, composure, and under assault. In many clips, we see people dancing — as they would during Levan’s sets at the Paradise Garage. The film features the Dougie, aching movements from Kahlil Joseph’s Flying Lotus-scored mini-filmUntil the Quiet Comes, Serena Williams Crip Walking on a tennis court, and Jafa’s son dancing at his sister’s wedding. Other bodies move in church, on the football field, at the front lines of the Civil Rights movement, and under the weight of a white police officer at a child’s pool party. As a composer would layer melodies, harmonies, loops, and rhythms to create sonic texture and vitality, Jafa’s masterful editing (described elsewhere as “microsurgical”) yields a gripping, urgent, and truly beautiful film.

Over the weekend, Love Is The Message made its Los Angeles premiere at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, where it will screen until June 12. I wondered what new questions or insights might emerge in a West Coast context (the artist incorporated footage from the city’s race riots, as well as a clip of L.A.-based artist Martine Syms). Jafa says he doesn’t view the film differently in different locations — but he’s curious to learn how others feel.

“Cinema is barely 100 years old, you know,” says Jafa. The artist explains he’s attracted to demonstrating what’s possible in cinema by “[subjecting it] to the same sorts of cultural, spiritual, social values as the other sort of African-American expressive modes — music, dance, oratorical stuff.” For Jafa, the nature of black expressivity is bound up in a central issue: self-determination. “When black folks articulate a radical articulation of themselves, it’s not just funny as a comedian, or musical in the case of musicians,” he explains, “it’s a kind of a demonstration of the capacity to be self-determined.”

He cites jazz as an example, an artform that foregrounds improvisation as a formal strategy, rather than adherence to an existing composition someone else wrote. We also discuss black comedy, as Jafa spent the weekend watching Dave Chappelle’s new Netflix specials. “I got into an interesting conversation with a friend of mine who was saying that she thought the black comedic space was a space that had the same sort of savage, ruthless freedom we associate with black music.” I pick his brain about Hype Williams, too. “It’s not only individual self-determination, but our collective self-[determination], and how we want to understand the world.” It’s also about resistance, he says.

Jafa tells me about a time he was speaking at a screening of Daughters of the Dust. “This woman stood up and said, ‘When I see Daughters, I don’t see a black grandmother, I see my own grandmother.'” Jafa wondered why the character’s blackness needed to be suspended in order for that recognition to occur. “How come it can’t be both? How come she can’t be as black as she is and you can still see your grandmother in her? It just really comes down to empathy, and one’s capacity to be able to see one’s self in another person’s circumstances,” he explains. “So when you refuse to understand or comprehend another person’s humanity, oftentimes it’s motivated — on some psychic level — by a desire to not want to problematize acting on your privilege in relationship to them.”

Jafa doesn’t believe movies can change people’s minds, but he does feel that film can “short circuit” this refusal of empathy. “On a certain level, I think that’s what Love Is The Message is doing. It’s really problematizing, if not outright short-circuiting, this refusal of empathy.”

‘Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death’ is on view at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA through June 12, 2017. More information here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Arthur Jafa, installation view of Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death, 2016, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome, photography by Thomas Müller