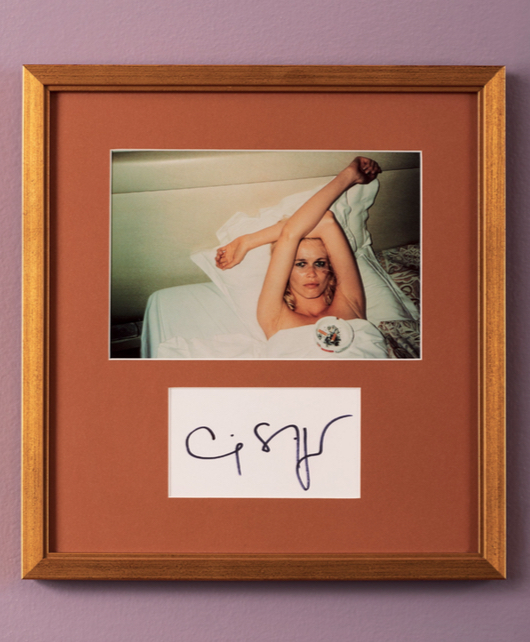

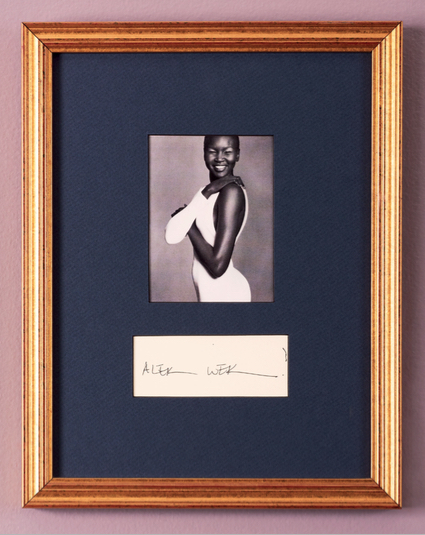

Models Matteris a yearbook-style compendium of muses. Written entries about the greatest models of our time range from ruminative text to a few offhand sentences, accompanied by vintage photographs shot by greats from Avedon to Scavullo. Lupita Nyong’o wrote a tribute of gratitude to Alek Wek for making her feel visible as a black woman: “It’s difficult to know what’s possible if we don’t see a version of ourselves in the world.” Juergen Teller wrote a single cheeky sentence: “Claudia, I just let her smoke,” he said of Schiffer’s sensuousness. Jacob Bernstein championed Lauren Hutton for being, basically, a baller: “a Voltaire-quoting Tulane grad, who didn’t have her teeth fixed, didn’t have drastic plastic surgery, and didn’t see marrying a plutocrat as the ultimate career move.”

All of these pop culture pairings were coordinated and compiled by French-born model obsessive Christophe Niquet. Niquet started his career in the fashion department at Self Service magazine, then moved to New York for his styling career over a decade ago. He has since started writing about culture and fashion for the French edition of Vanity Fair. Models Matter is his first book, though he has two others in the works (a 1960s fashion photographer monograph and photo book about women in New York).

Niquet discusses his home-made “model database,” his impatience with the industry’s tokenism, and his deep nostalgia for the models of yore.

Steven Meisel states in his introduction: “Nowadays, models have become overexposed, marketed, disposable.” Was there once a golden age of modeling? If so, how has the industry changed since?

I agree with Steven that models have now become overexposed. In the past, models were at the forefront of pop culture—the 1960s youthquake, the supermodel era of the 1990s—but there was still some mystery surrounding them. The personalities were big and their style was fascinating. It was generating press coverage, not Instagram likes. The overexposure of models today is something completely different.

The 1960s was the rise of the post-Second World War teen generation. It was a group of young women with a rebellious attitude towards style and towards life, documented by a group of young photographers. Their sense experimentation led to the end of haute couture and the rise of boutiques.

The 1990s was a time for excess: big money, the Concorde, a thriving industry that could justify creating its own superstar system and reward the faces that sold products with multi-million dollar contracts. All the girls of that era were young women, not children. They could interact with head designers, with the publishers of Condé Nast or Hearst. They were given power and they kept it to control their careers.

The flip side of that coin is that it accelerated the rhythm and hunger for the next “super,” causing the fast turn-around of faces we see happening today. What we are left with now is children of celebrities modeling for brands due to their name recognition, big contracts and magazine covers going to actresses, and an endless flow of forgettable new faces that disappear as fast as they arrived.

What about the model-actress transformation? Steven Meisel states: “A great model is a great thespian.” Jacob Bernstein clearly sees it differently: he said Lauren Hutton was “one of the rare few who became an actress and didn’t embarrass herself.” How do you see these roles of model/actress combining?

They are talking about two very different things. Meisel speaks of a school of modeling that is interpretative; Jacob speaks about a transition from this silent act into movies. Great models all have to possess this skill of projection, but that doesn’t mean they will be good actresses. The skills required for each job are very different. Few models become legit successful actresses, but enough do for the idea to remain a dream. Kim Basinger, Rene Russo, Uma Thurman, Lauren Bacall, and Capucine all started out as models, and all had great careers as actresses.

What does your role as “archivist” entail?

Archivist is a beautiful and flattering word but you could also use: a very organized and active model fan. I turned a personal obsession into a database. There are a few models for whom I have a deep, passionate love, and I wanted to find every picture ever taken of them. So besides the autographs and anecdotes, I avidly collect vintage magazines—Mademoiselle, Vogue, Bazaar—from the late 1950s to the late 1970s. And every book I can find on models and modeling: biographies, autobiographies, self-help books by models, books on second acts. I love knowing the life stories of those women. Most come from humble beginnings and use fashion as a tool for personal reinvention.

“You either got it or you don’t,” David Croland says of Marisa Berenson. Do you agree with this? Is being a model something innate?

It is! First there is a physical aspect to being a successful model: you just can’t escape height, good proportions, and beauty. But with ease in front of the camera and pleasure in wearing clothing, great models can break the mold.

How did you decide on the contributors to the book?

I created pairings; I knew the relationships, personal or professional, between the women and the contributors, from stories they had told me in private. What all those anecdotes highlight is the ability a model has to create magic and inspire fantasy—in image-makers’ brains as much as for magazine readers and consumers of luxury goods.

There are two mentions of “transgender rumors”: Carole Sabas on Amanda Lear, and Amy Fine Collins on Capucine. Their gender mysteriousness or androgyny was seen as an asset. Do you think a model’s role is to confirm, or to confuse, the notion of femininity?

During the times of Amanda Lear (late 1960s) and Capucine (1950s), androgyny was still something new. Woman were not allowed to wear pants in fancy restaurants in Paris or New York. Androgyny was in the behavior and the attire, not the physicality.

That was then and this is now. We are becoming more aware and accepting of the trans population, but I wish we wouldn’t use their identity as a marketing tool.

Can you elaborate?

I would be very happy if we could finally stop putting labels on people. What is trans beauty, black beauty, Asian beauty? It is all beauty. If someone wants to be the poster girl for trans beauty as a choice so be it, but I look forward to the day where it could remain private if that’s what they decide. Models should get the cover of Vogue for their beauty, not to accommodate a cover tag line that dangerously plays with sensationalism.

As we become open to differences, trans models finding representation is more and more possible. We see a new generation of girls—like Lea T or Andreja Pejić—get spreads in magazines and for advertising, so it makes sense that modeling agencies try to replicate their success and open up to trans models joining their ranks. Representation is about integration and acceptance. Sometimes a “trend” can become detrimental to a cause.

But it’s not always a trend. Black model Bethann Hardison said about Beverly Johnson: “The cover of American Vogue didn’t seem like a battleground in the struggle, but we won it.” What do you think the media’s role is, in terms of this “battle ground” of representation?

This is a difficult one to answer right now, because what is the media now, and who has the power of information? There are some wonderful models working today with unusual beauty who don’t get face time in the pages of Vogue. All they need is a social media presence. The reach of some monster brands is enough to shine a light on a model and make her a star. An exclusive turn on a runway will do as much as, or more than, a magazine cover, if relayed massively on social media.

The fashion press, especially print, is still very timid about breaking the mold they are happy with. Whenever a mainstream magazine puts a plus-size model on their cover, or a model that is not white, or over 40, they pat themselves on the back and scream it loud: “look at me, I am open to people looking different.” And as long as they do this, our perception of beauty will remain unchanged. Why is it so special to use a Sudanese beauty on a cover? Why is it so special to use a woman over a size 4?

Right, celebrating diversity once in a while doesn’t mean much, if the commitment to representation overall is still incredibly disproportionate. Whose responsibility do you think it is to simply normalize a diverse point of view?

The responsibility is on everyone. Magazines have to stop living with that archaic idea that a non-white model will sell less covers than a white one (and with actresses on the cover each month, how do they even know). Agents have to believe that there are more than three slots to be allocated to non-white models in runway shows, and start considering their models as unique and not disposable. Editors and journalists have to stop thinking of non-white models as exotic birds and work with them the same way they would a white model. And finally, the consumers should use their money where it matters. If you feel you’re not included by a brand or a magazine, go buy something else. Diversity is not a gimmick or a sales argument. In 2017, it should not even be a conversation anymore.

What about the title, Models Matter? Why does their role, ultimately, matter?

Unfortunately, over the past few years, models matter less and less. Their careers are shorter, the inspiration they provide to designers or photographers has shrunk, and the way they are treated has worsened. Maybe the multiplication of working models and fashion magazines, as well as the frenetic rhythm of fashion weeks, has made the faces and the bodies that inspire and sell the product less relevant. We need more, need it fast, and need it cheap.

But models matter because they become the faces of their times, and ours. They usher new ideas of beauty into the world. And models matter to the fashion industry: they make the dreams of creators come to life.

Models Matter by Christopher Niquet, published by Damiani, is available March 28th, 2017.

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

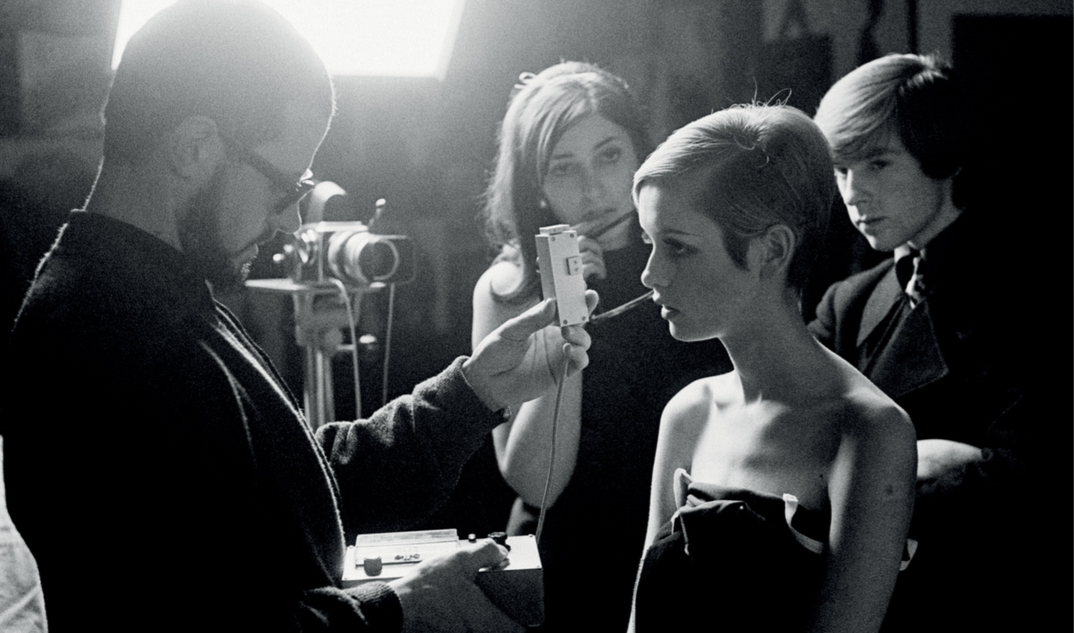

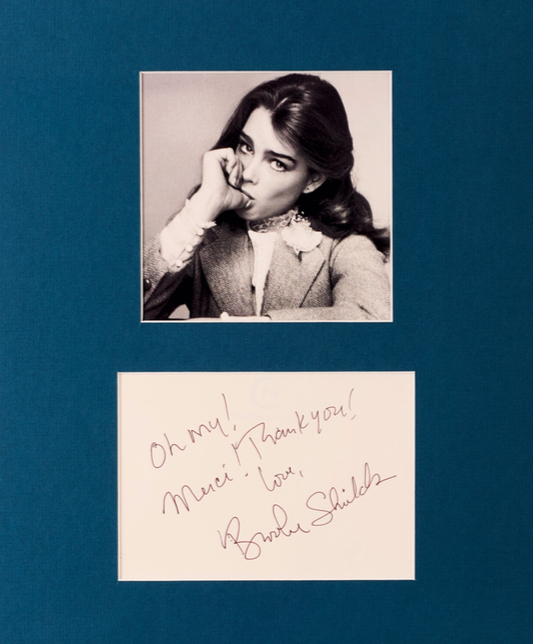

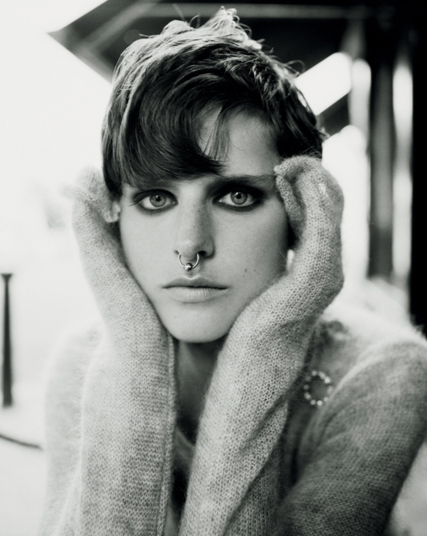

Photography courtesy Models Matter, Damiani (Top to bottom: Twiggy by Burt Glinn/Magnum, Brooke Shields by Unknown, Claudia Schiffer by Juergen Teller, Stella Tennant by Steven Meisel, Mouche by Giancarlo Botti, Alek Wek by Steven Meisel)