When I was a kid, my grandparents took me on an amble through the Suffolk countryside one hot summer’s day. I fed white sugar cubes from my splayed palm to the chestnut pony that lived in the field by the local church; I bopped down in the long, dry grasses and held staring competitions with the crickets, whose singing made the meadows sizzle as though every hill was toasting beneath a grill; and I tippy-toed along the thick wooden telegraph poles stacked horizontally by the side of the dusty road, serving as circus balance beams for my six-year-old self while they waited to be erected by builders.

They’d been treated with creosote, and oozed a tacky mix of sap and tar that stuck to the soles of my apple-red T-bar shoes. It was so baking that the hazy horizon shimmered like a dream sequence in a low-budget film, the air crinkle-cut, pressed between 1988’s fashionable crimping irons. Under the heat of the sun, the poles huffed out a distinct, strong smell of chemicals and pine.

That exact same scent engulfs me every time I climb a certain staircase inside King’s Cross underground station.

London’s tube lines are a long, long way from summery Suffolk. There’s nothing in that stairwell that should give off such an odor. And noone else can smell it. Because it’s not really there.

I have synesthesia: a condition where specific triggers in one of the senses — sight, for example — give rise to “ghost sensations” in another, such as taste or touch. According to the National Health Service, about 4 percent of the UK population have it, but it’s expressed in different ways: some people get a flavor in their mouths when they read set words, or see shapes and colors in their minds when they hear music.

My type of synesthesia is comparatively rare. I get “olfactory hallucinations”: I experience smells that don’t exist. These aromatic apparitions arrive either when I feel certain emotions, encounter people I know, or move through familiar locations. They are utterly realistic — they even smell stronger if I inhale harder — and at moments overwhelming.

Liverpool Street concourse reeks of Hoover bags full of dust and hair. Finsbury Park gives me cardamom pods; Leyton lathers Johnson’s Baby Shampoo right beneath my nostrils. Euston smells cold and glassy and tense, like the air before it snows.

There is no obvious connection between my triggers and the perfumes they conjure up. And whilst the perfumes can sometimes remind me of legitimately associated memories, these too have no ostensible link to the original stimulus. So walking up unremarkable station stairs can randomly make me smell creosote and transport me to past pleasures with my grandparents, when I was only planning to travel to Hammersmith. It’s a muddled yet often marvelous domino rally of sensations and recollections. Where my nose goes, nobody knows.

I’ve just moved apartments, and for two weeks I wondered where my housemate was hiding the cherry bakewell cakes, before I realized that whenever I was content and relaxed in my new home, the air filled with the phantom fragrance of almond fondant. Sniffing invisible Mr. Kipling cakes, appropriately enough, is a sign I’m feeling Exceedingly Good.

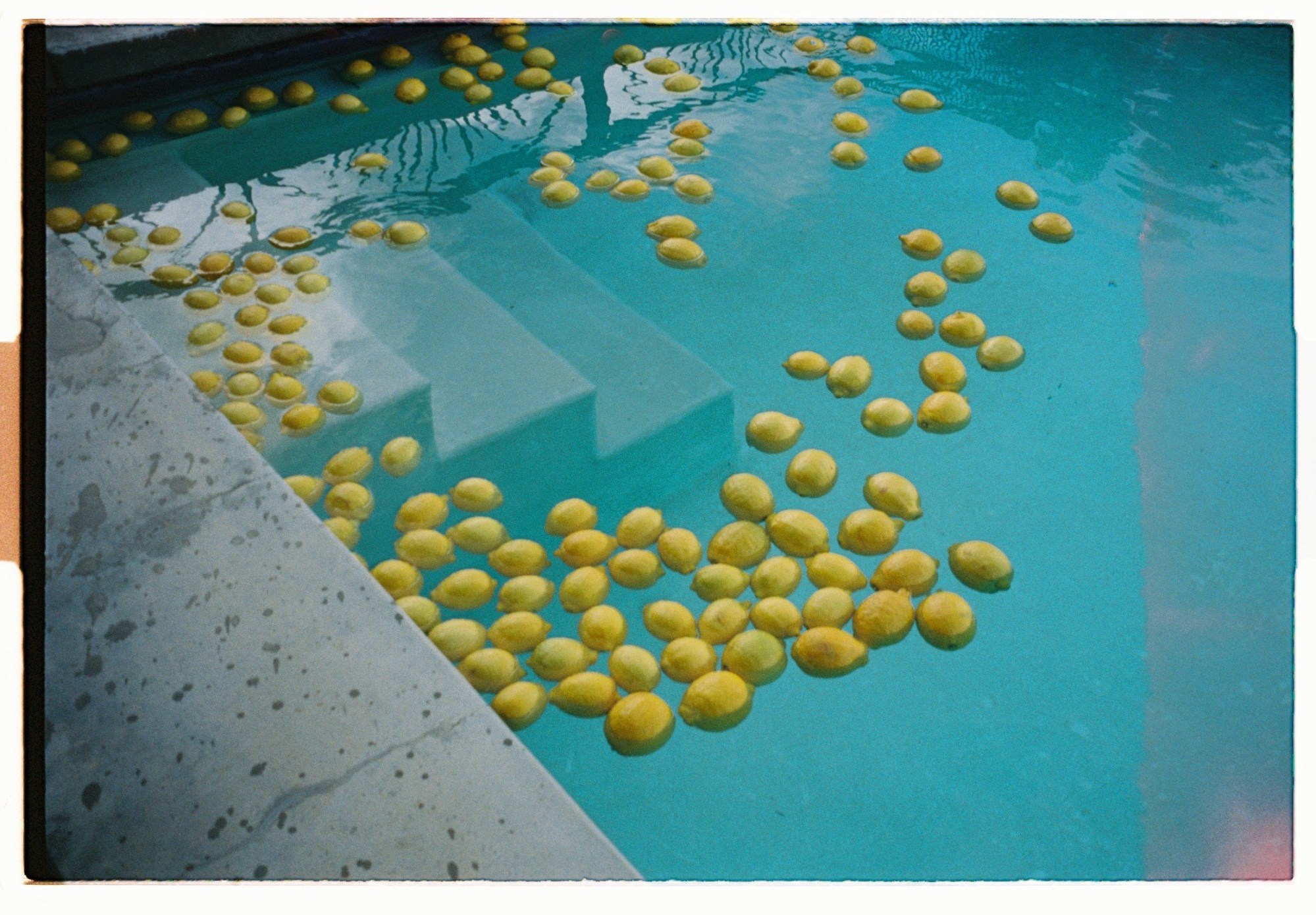

Happiness exudes sweet scents. Unexpectedly bumping into a friend I adore is like walking into a bakery where trays of Danish pastries and cinnamon buns are being shimmied out of steaming ovens. And falling for someone is frequently accompanied by delicious sugary lemon notes: washing up liquid, yellow bonbons, sherbet. If my main squeeze begins to acquire a freshly squeezed tang, then love is in the air. I can smell it.

But on occasion, my synesthesia is confusing, unpleasant, or even upsetting.

Horribly, stress can vividly evoke the stench of sanitary disposal bins — the odor of blood and body fluids combined with sickly sanitizer. It’s nauseating, and deeply unhelpful if I’m trying to keep calm.

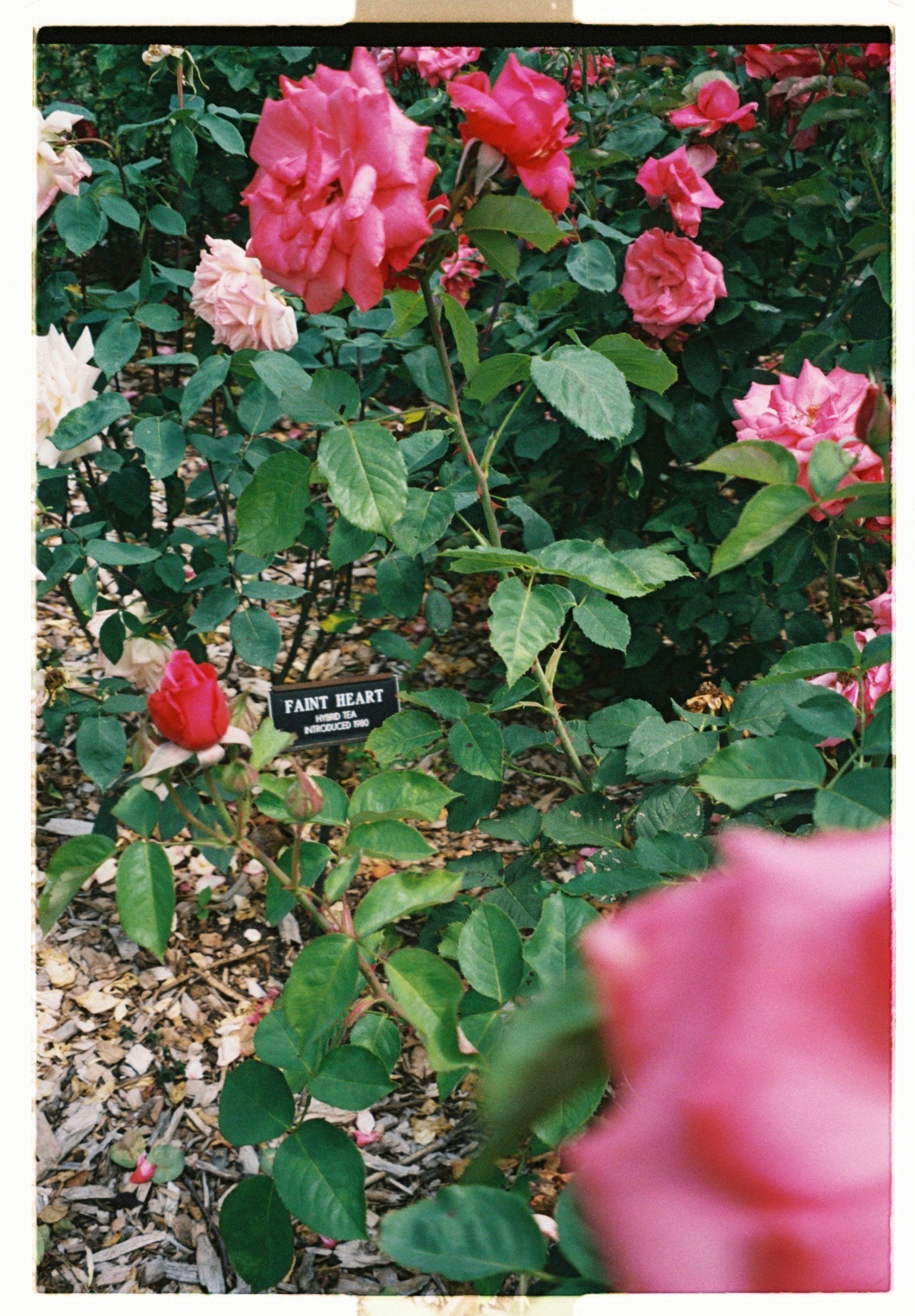

An ex-partner started to smell of unripe tomatoes growing in greenhouses: a tangy, chlorophyll zing that I craved, and which provoked cheery childhood memories that made me feel safe and comforted. Yet while he never had a fishy odor, his smell was a red herring. He was dishonest, but his fragrance encouraged me to trust him. It can be hard not to over-attribute meaning to olfactory hallucinations when they are so potent. I stayed with him far too long, in small part because I didn’t know whether to trust my gut or follow my nose.

Another man who was truly beautiful both inside and out gave me smelly visions of cheap polyester and plastic each time I met him, no matter how much Issey Miyake he spritzed on. He was so down to earth, yet he smelled eerily fake and fabricated. I ignored it, but can’t deny that it unsettled me.

I’m pretty sure that I became synesthetic in my late teens. I suffered a humongous allergic reaction at the age of 17 while working as a waitress; doctors still don’t know the cause, but by the time I got home from my shift my face was so puffy that my mom thought I’d been beaten up, and I couldn’t hear because my ears had swollen shut. I lost consciousness, and was stricken by seizures for years afterwards. Synesthesia can result from damage to the brain which causes neurological wiring to start misfiring.

Juliet Slide experienced similar olfactory hallucinations to mine after being hit by a bus while using a pedestrian crossing and sustaining major head injuries. “Whenever I felt stressed, I’d smell burning plastic, while the scent of cinnamon accompanied sensations of serenity, elevating them to an almost spiritual sense of ecstasy,” she says. “As I began to heal, nerves binding like ivy, my grey matter rebuilding its webs around the scar tissue, the smells changed. One day, I drove past some council lawnmowers trimming the grass verges, and the odor of cooking vegetables filled my senses. Clearly, my brain couldn’t find the correct scent file, but bodged the job with something it considered similarly ‘green.’ It made me laugh out loud. Yesterday, I smelled hot croissants, together with an overwhelming sense of peace.”

Scott Mataya had a stroke a decade ago that nearly killed him. Now, he’s a ‘multi-modal synesthete’: all his senses interact in non-standard ways, including his perception of scent. To him, raspberries taste like a certain shade of blue; flecks of light and sparkles of sound appear around someone if he thinks they’re dangerous or lying; and musical instruments blast out bouquets when played.

Plus, like me, one of the most intimate parts of his life is affected by synesthesia: sex.

According to how and where I’m being stimulated, my orgasms variously smell like sweeties (Haribo Kiddies Supermix, of all awkwardly inappropriate treats for so adult a circumstance), red licorice, or custard donuts. And one of the most breathtaking, headswimming climaxes I’ve ever shared with a partner was redolent of sodden potting compost and jasmine — a flower bed in my bedroom, that gave the impression of being gratefully buried alive.

Scott reports comparable “earthen scents” and “a charge of orchids” when he comes, as well as “orange and purple fog and gossamer light.” If his lover has washed with simple white soap, “it’s like his body becomes a checkered picnic cloth.”

Although, as with Scott and Juliet, my nonsensical sensory mismatched mirages are most likely caused by trauma to the brain, skewed neural pathways leading my nose up the garden path, I’m reluctant to pathologize my condition when it’s often so luscious.

I’m hoping to work with Dr. Trudy Barber from the University of Portsmouth, who has been researching synesthetic orgasm with a view to recreating individuals’ experiences using virtual-reality technology. So perhaps soon, neurotypical folks will be able to witness what it’s like to get a lungful of love or breathe in bliss, too.

Synesthesia is nothing to be sniffed at.

Credits

Text Alix Fox

Photography Claire Arnold