A legend in his native New Jersey, DJ Jayhood has spent the last 12 years defining and redefining the high tempo ADHD chaos of Jersey Club music. As with most Jersey producers, Jayhood’s music is built from samples cribbed from everywhere and anywhere, with little attention paid to copyright or fidelity. Jersey tunes are as likely to sample the latest viral meme as they are whatever this week’s major label hip-hop hit is — often colliding on the same track, samples mangled into stuttering, kinetic bursts of sound, like a glitching WiFi connection laid over a relentlessly 808 bass kick.

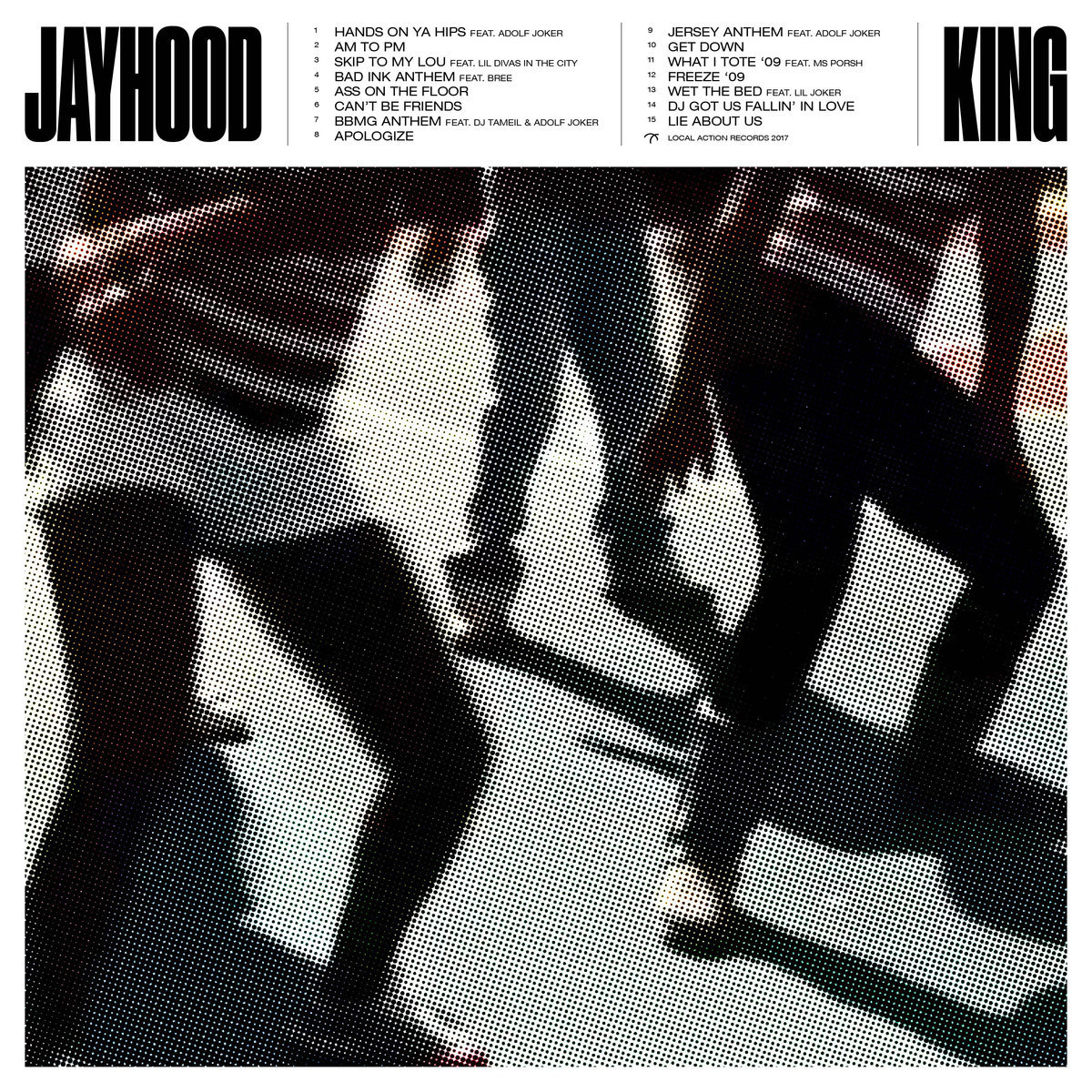

While Jayhood is famous in Jersey he’s less known outside, largely because his music has never been released in any ‘official’ capacity. Instead, his tracks have existed on Soundcloud, or YouTube, or on bootlegged CDs. Often these tracks take on a life of their own, with uploads to Soundcloud being ripped by Jersey dance crews, then re-upped to YouTube with an accompanying dance routine, pushing more listeners back to the original track in a cycle that keeps turning. This has put Jayhood in a particularly modern bind; he’s racked up millions of plays without selling a single record — all the while influencing web geeks from London to Sydney to create their own response to Jersey Club sound (often doing well as a result). Now that’s about to change — UK tastemaker label Local Action has signed a retrospective of Jayhood’s career. Entitled King, the album pulls together his biggest tracks, and represents a chronology of a genre that he has been fundamental in developing. Listening through King is a thrilling, disorienting experience, where constantly familiar tracks and samples are carved into stuttering plosives; the hectic onslaught of information that batters our modern lives transmutes into a ballet soundtrack for inner cities.

How did club first get started?

Club music started in Baltimore. DJ Techniques in Baltimore was the first guy to put together the club beat, the drum pattern. Then a guy called DJ Tameil bought it from Baltimore to New Jersey. This was in the 90s, or maybe the early 2000s

It’s such a full-on sound — was there anything beforehand that prepared people for club music?

It kinda came out of nowhere to me. I was a kid, I was around six or seven when I first heard the music. From the moment I heard it I fell in love with it, I was like, “Damn! There’s just something different about this. It’s dope, I don’t know what it is but it’s dope!” I never thought that one day I’d be making it, I just used to dance to it. So then I started to find out who Tameil was — the sound was already big at that point, and it had a real good feel to it. Then they had the next generation of producers like me, DJ Joker, DJ Sliink, and once we came we made it more fun — that’s when all the dances became a part of the scene.

Where did you hear the music? Was it in street parties or clubs or what?

You’d hear it on CDs. It started out with producers putting tracks on CDs and you hear people playing them in cars, at block parties, and in the clubs.

What were the parties like where you’d hear Jersey played?

The parties were crazy. They’re not the same as today, but they were definitely crazy. People would be like — even at house parties — they’d be insane. House parties were crazy, people would be getting broke through walls from the dancing. Even at the big venues, you could come in a fresh outfit and you definitely be leaving all sweated out. Your hair was done. All sweated out. You might even leave a few pieces of clothing because the party was just so crazy like that.

So when did dancing turn into producing for you?

I started producing… ahh… I had to be like 13. I’m 25 now. I started writing beats on FL Studio.

And what was the first song you did that broke through?

Definitely “Apologize.” It was a remix of “Apologize.” That was a big party hit. But then “Heartbroken” was one of the first remixes I did that people went crazy for.

And that was a remix of the UK tune “Heartbroken” by T2? Was that a big tune in Jersey anyway?

Yeah. A couple of my friends have told me that “Heartbroken” was a big tune in the UK.

“Apologize” and “Heartbroken” were based on samples — will you sample from anything?

Yeah definitely. Most of the time me and my friends are just driving around and we might hear a song on the radio and think, yeah I should sample this. Or I’ll be in the club and I’ll Shazam what I’m hearing then go back home and resample it.

And what about that bed squeak sound? It’s become such a distinctive part of club music, do you remember how that came into the music?

The bed squeak? Honestly, I can’t define that. I don’t know that one person introduced that — I want to give credit to everybody, I wouldn’t say that one person did it.

None of your tracks have come out properly in the past — they’ve not been on iTunes or anything similar — so how were people hearing it up until now?

At first I was just uploading songs to Myspace, and we went from there. We went from Myspace to another site to another site, and then once Soundcloud came out, that was the biggest way for me to get my music out there. I was never a big man for putting stuff on YouTube.

It’s funny you weren’t too big on YouTube, because a lot of your tracks have been really known for having dance videos made to them — were there any that really blew up because of the dance videos?

Yeah, definitely. “Hands on your Hips,” which I did with DJ Joker. That was my breakout record, as far as my visual and my voice getting heard. I’d had some other hits like “Patta Cake Patta Cake,” but “Hands on your Hips” was a worldwide hit.

Some people in the Jersey scene have claimed that when the sound did blow worldwide, it was jumped on by producers in other countries without proper credit being paid to the originators. What’s your take on that?

I personally don’t get upset about it. I think it’s pretty cool. It’s like this; I’m pretty sure there’s a lot of people in Atlanta that don’t like that we do their style of music, but it’s still a great sound. People should be happy that we’ve got people all the way over in the United Kingdom replicating our sound. Long as they paying us respect — and they do! They pay us for our music — people out here don’t even wanna pay for music, but you got people in the UK that don’t mind spending $10 on one song because they respect what we do. So I don’t get upset because we got people in other countries making Jersey club, this is making it bigger for everyone. Everybody wanna be mad upset about something, but the real people who make this what it is, they’re not even getting upset. I’m not complaining about nothing — through my hard work I’m getting my album released on Local Action, that’s pretty dope!

Traditionally in America, slower tempos tend to be more popular. Can you see a time when the Jersey sound can be popular across the board?

It’s definitely getting there. This album is going to set a bar. And working with Missy Elliott and her artist Sharaya J — we wrote the Sharaya J record Banji which went worldwide — that helps. I think if we land a record with Missy now that will make Jersey a whole lot bigger. So we’re focused on that to. We’re working on some new stuff for Missy right now — I’m in the studio with my buddy DJ Joker. We’ve got to just keep pushing that sound.

Credits

Text Ian McQuaid