Nicolas Bourriaud is a star curator of an intellectual mould we see less and less at top levels of public art. He co-founded Paris’s Palais de Tokyo, in 2009 curated the fourth Tate Triennial, and until 2015 was the director of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. When he was dismissed by culture minister Fleur Pellerin many in the art world suggested the position had been made available for a friend of Francois Hollande’s mistress.

But as well as making headlines, he’s an old-school art theoretician, publishing book-length treatises that, unlike much modern art theory, people have actually read and found influential at the zeitgeist level. Relational Aesthetics, published in 1998, was seen to speak for a generation of artists in the 90s and the changing way that art was being presented and experienced: a public social context ousting the private communion between work and reverent viewer. Nowadays, we can see this as looking forward to the age of social media, where we are instantly able to witness or participate in other people’s experience of images. Art, for Nicolas, should overflow the traditional boundaries of the work and even the gallery.

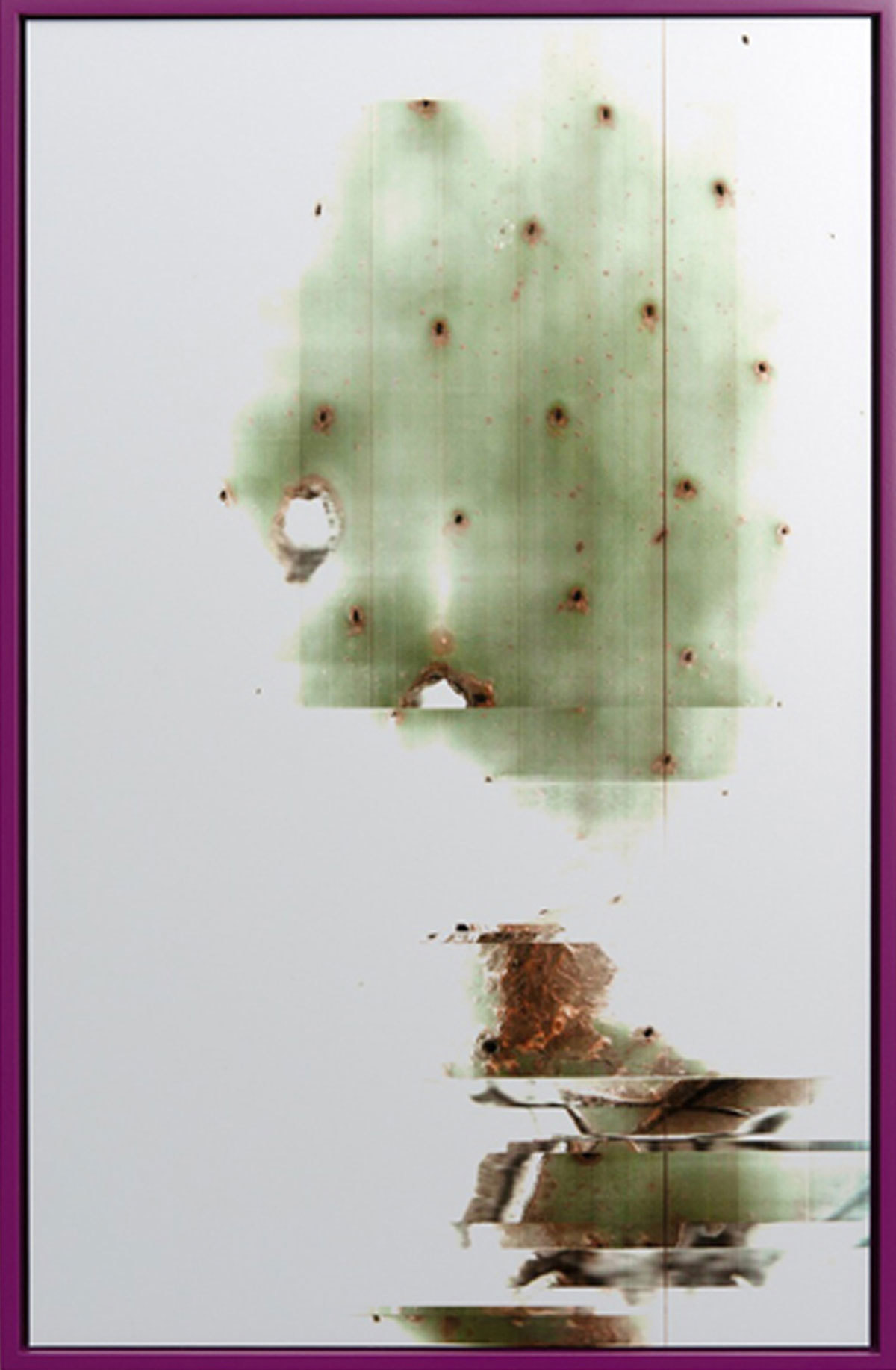

This holistic approach is reflected at La Panacée, Montpellier’s contemporary gallery Nicolas now directs. Its regular-looking cafe, on closer inspection, turns out to be an innovative restaurant. (Nicolas also finds the time – as well as laying the ground for a big new contemporary art museum called Montpellier Contemporain, or Moco, in 2019 – to be a judge of The World’s 50 Best Restaurants. He told me this at La Panacée over a meal of black focaccia presented to look like beetroot and stone bass in coconut sauce with singed raw cabbage). And walking into the first French solo show of Iranian-born LA artist Tala Madani, what begins with four dutiful studies of light emanating from apertures – out of open doors, through bars (Talisman IV and III respectively) – gives way to light emanating from people’s arses.

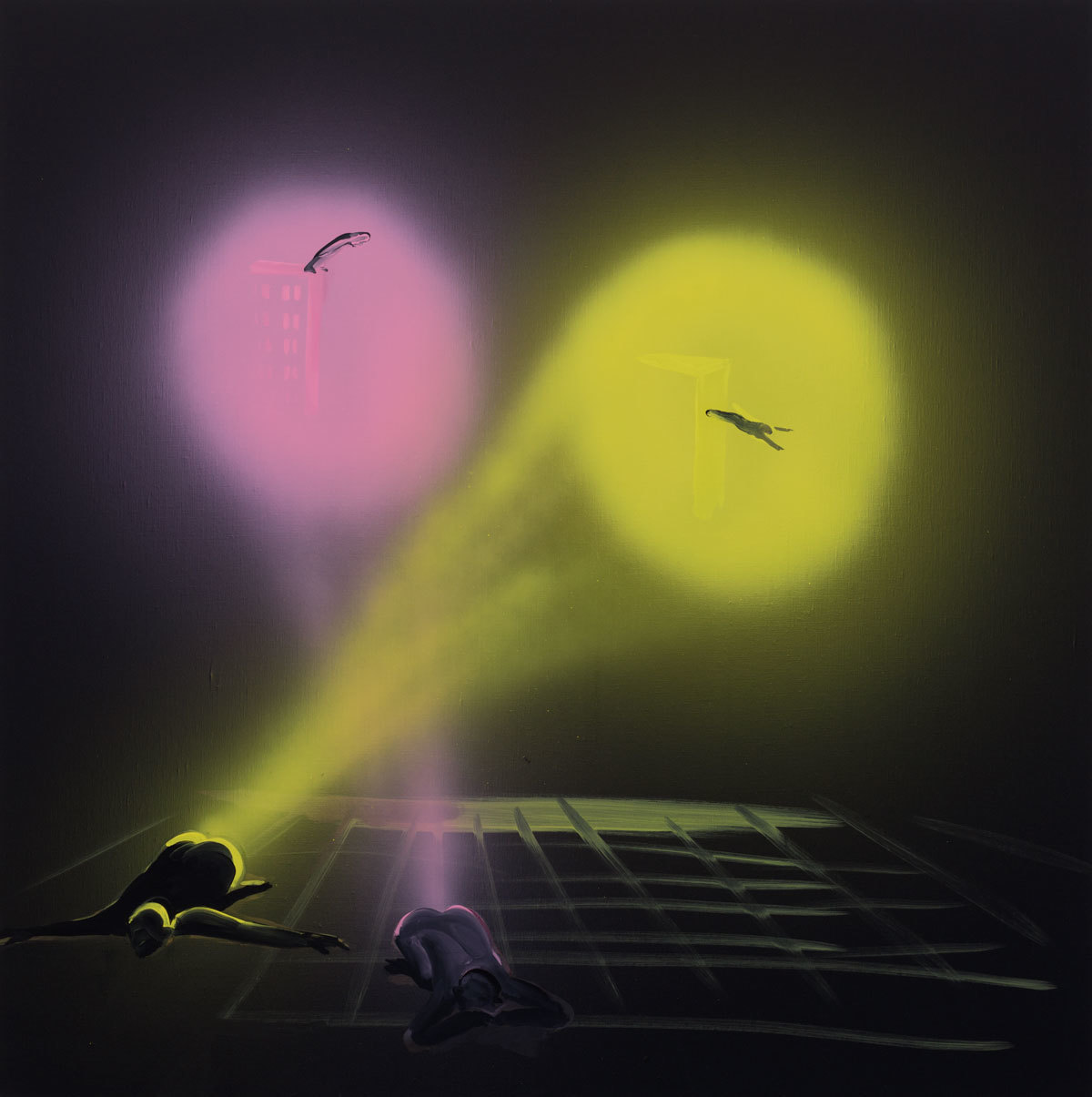

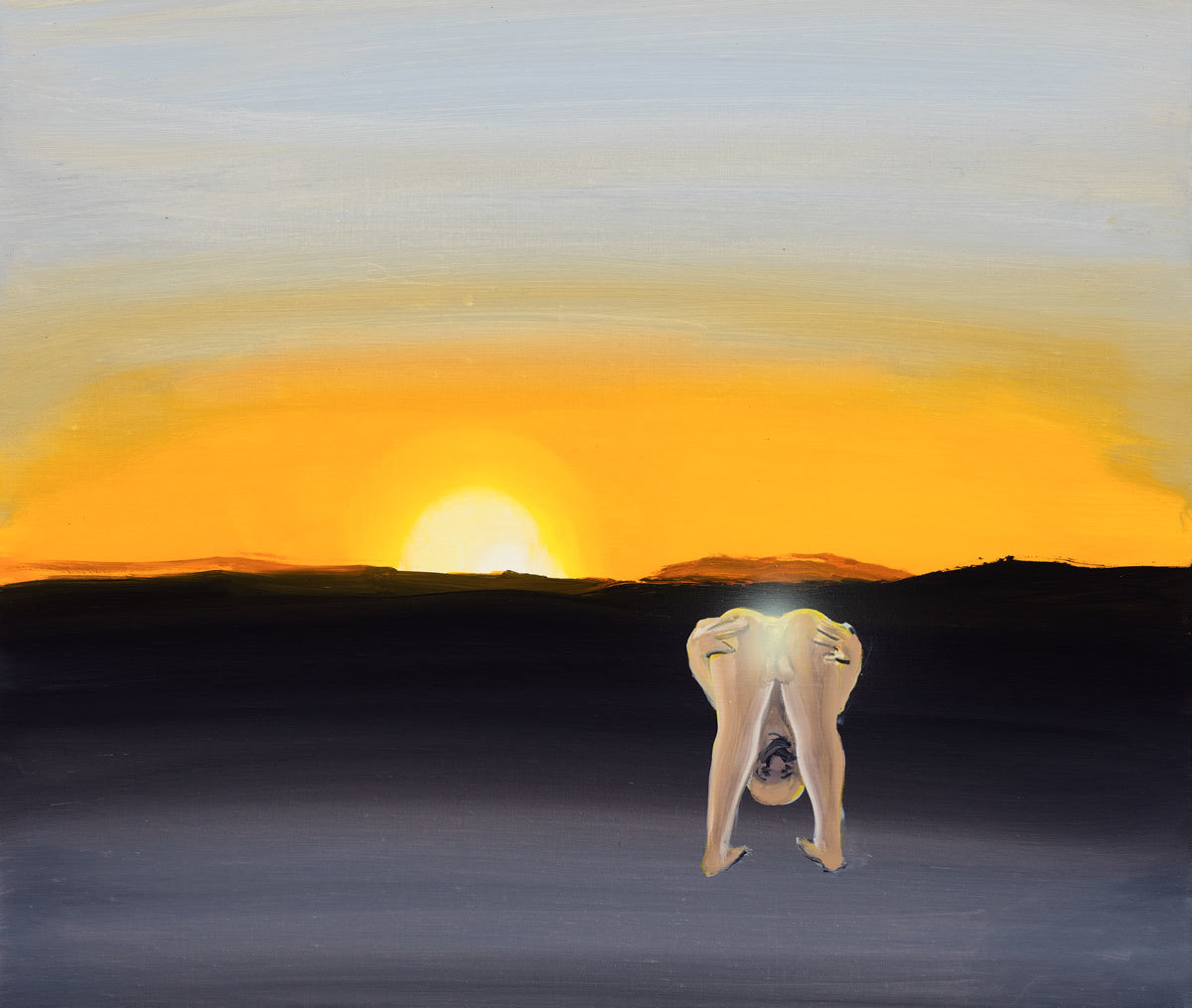

Madani’s figures are sometimes gender ambiguous but mostly men. They are cartoonishly painted but placed on the canvas with an understanding of composition and chiaroscuro: a powerfully demonstrated source of light rendered via spray gun, drawing the eye. In TBC (2016), men on high stools are arranged in a sort of strip club setting, backlit by an intense white while also generating their own yellow and red light sources. In Double Suicide (2016), two figures project spotlights out of their arses which illuminate a further two figures jumping off buildings. Sun God (2016) is a sunrise scene that features a naked man bending over, scrotum visible, and another sun shining literally out of his arse hole at the viewer.

Madani’s canvases undoubtedly make you LOL. This feels instantly puerile and inappropriate, but only before you realise this self-censoring is silly. It plays right into our preconceptions not only about how art should be appreciated, but visibly reacted to in a public space. It feeds into Nicholas’s ongoing preoccupations, just as the gallery itself continues to echo Madani’s works after you leave the room, the exhibition being placed opposite large windows onto a leafy but modern courtyard whose light reflects on the walls.

This idea of the show not ending, or starting, at conventional parameters is a feature of Nicholas’s centrepiece exhibition: Back To Mulholland Drive. He had the idea for the show, which features 24 artists, including Alisa Baremboym and Adrien Missika, responding to David Lynch, after seeing the palm trees as he arrived in Montpellier. It reminded him of the macabre Hollywood featured in one of his favourite films. This is strangely apt. Someone from the Mayor’s office had told me they would like the city to be considered “The Los Angeles of France.” Here at the beginning of spring, and not completely coinciding with Montpellier’s allotted 300 yearly days of sun, there is something uncanny about the Mediterranean in dormancy.

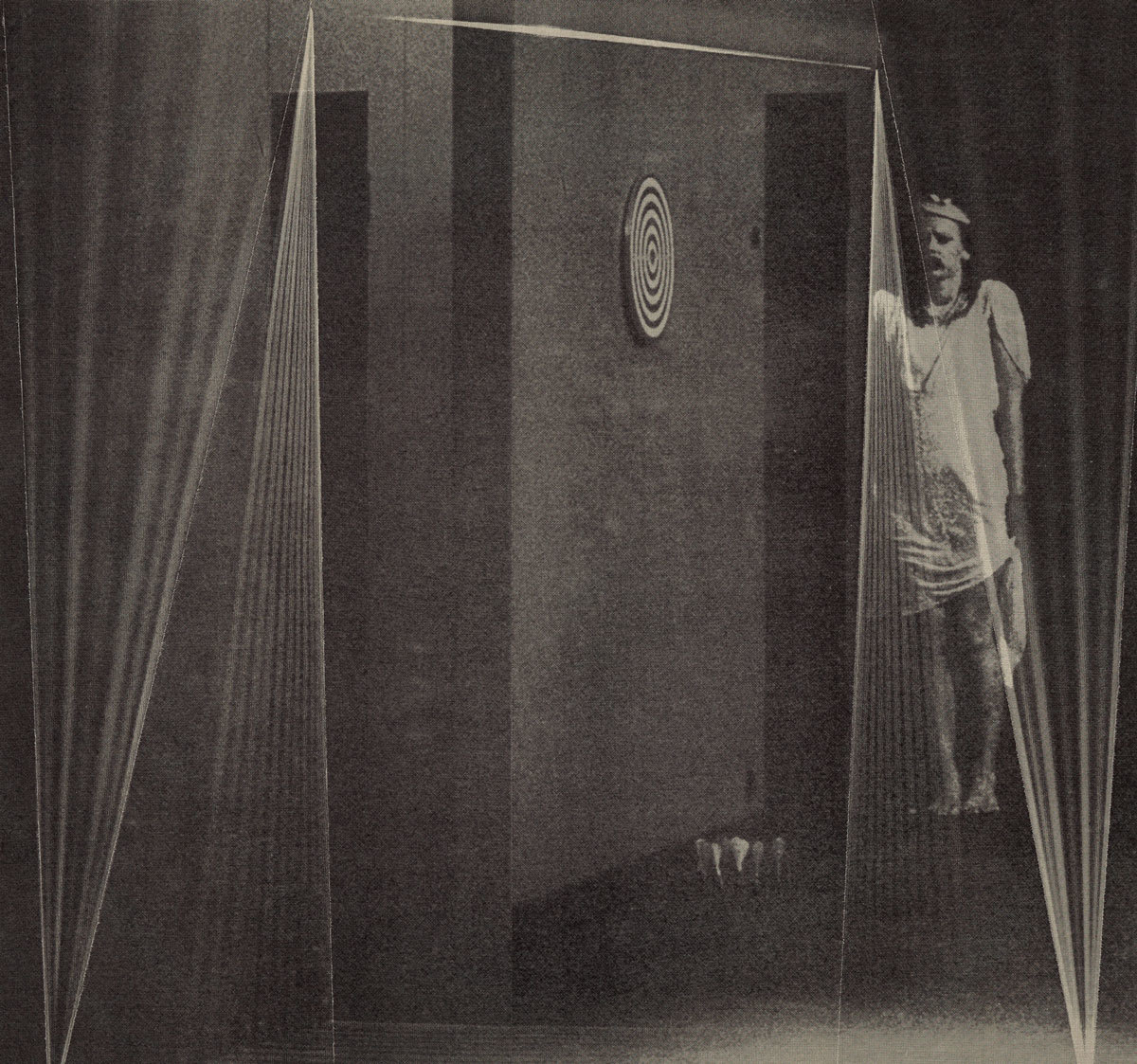

A perfect setting for a show that examines how Lynch secretes the macabre and surreal within the everyday urban or suburban landscape, and also how avant garde visual artists have, for a while, been drawn to the banal. Bourriaud calls this “Fantastic Minimalism”. Some of the “responses” in the exhibition existed decades before the film was even made, such as Wendy Jacob’s The Somnambulist (blue) from 1983, in which forms slowly inflate underneath blankets, as if breathing, strangely prefiguring a moment at the opening of Lynch’s film where sounds of breathing are heard as the camera focuses on a blanket.

But before you can see much of the art, the gallery goer might notice teenage shrieks from around the corner. In this passage there is a dumpster made of canvass by Kaz Oshiro like the one behind Winkie’s diner in the 2001 film. Walking towards it recreates the ominousness of watching the scene, and if you look through a peephole at the end of the passage you will see a topless woman covered in the same sort of dumpster grime as Lynch’s famous monster, advancing towards you, making noises, or painting words like “Heaven” on the wall. The performer is literally inside the wall.

Lynch’s influence has invaded visual culture like one of his murderous spirits. This isn’t just in terms of obvious homages: dream sequences in The Sopranos, Vic and Bob sketches and everything Lana Del Rey has ever done, etc.. Lynch can be felt in anything where a criminal wears a mask; in every soundtrack or song featuring a bowel-releasing synthesiser drone. The Lynchian has almost become normal.

This is doubly true for the French, who have always got Lynch more than most. The financial backing for several of his films since 1997’s Lost Highway has been French, and in 2007 he joined the relatively few foreigners be awarded the Legion d’Honneur. Standing in this exhibition, immersed in a High Art response to a high-art movie, and there being a host of regular gallery goers lead by an enthusiastically pedestrian guide, and teenagers shrieking at the dumpster from Winkie’s diner, and it being not only unpretentious but thoroughly engaging, is a Lynchian experience.

Tala Madani and Back to Mulholland Drive run at La Panacée until the 23rd of April

Credits

Text Jonathan McAloon