Beyoncé began her Grammys performance last month by flaunting her swollen belly and donning a golden baroque headdress in another Lemonade-era reference to the Yoruba goddess Oshun. Meanwhile, projections of the singer appeared and dissolved according to the numeric rhythms of the Fibonacci series, and the poetry of Somali writer Warsan Shire reverberated in our ears. This disorienting stew of virtual reality and live performance, mythology and art, Western and African references, concluded with a tableau vivant in which Tina Knowles (Beyoncé’s mother), Beyoncé, and Blue Ivy sat together posed like royalty. Here were three generations of black women staring right at us: the past, present, and future of blackness.

Beyoncé’s performance was afrofuturism on steroids. Performed to an audience of 26 million, it was a pivotal moment: afrofuturism, a black aesthetic that has been curated and developed since the 70s through sci-fi films like Space is the Place and Blade, the writings of Octavia Butler, and the jazz of Sun Ra, was entering its largest platform yet.

What is afrofuturism? Even afrofuturists struggle to answer that succinctly. The aesthetic is multicultural, transhistorical, and concerns itself with the past, present, and future effects of the African and black diaspora. Professor John Jennings, co-curator of last year’s New York Public Library exhibition Unveiling Visions: The Alchemy of the Black Imagination, explains the pluralistic aesthetic like this: “Afrofuturism is not science fiction, but about imagining different spaces of creative thought that don’t put your identity in a box.” Still, afrofuturism is better seen than explained. Pop blessings like Solange’s “Cranes in the Sky” music video, Janelle Monáe’s ArchAndroid album cover, and TLC’s “No Scrubs” video could all be listed as “Required Viewings” for an “Afrofuturism 101” course.

As the aesthetic enters the mainstream, here are six artists using afrofuturism to explore the identities and lives of African and black people in 2017.

Olalekan Jeyifous

“Afrofuturism doesn’t exist as prominently in the public imagination as I believe it should and can,” says Olalekan Jeyifous, a Brooklyn-based artist and designer. A graduate of Cornell University, Jeyifous makes work that imagines what the future of Nigeria, his home country, could become. His latest project, Shanty Megastructures (on show at the Museum of Art, Architecture, and Technology in Lisbon this month), features 360° virtual-reality renderings of futuristic African metroplexes. Cars fly in the air, wind turbines spin, yet, despite all the eco-technological advancements, the distinctive shanty buildings found in cities like Lagos remain. Jeyifous firmly believes in the power of afrofuturism. “There’s a slow-evolving tolerance for the different and the weird and a broadening of the acceptable and the possible,” he says. “For instance, look at what artists like André 3000 did for our perceptions of your average menacing and masculine rapper. 10 years later, you have a guy from the Deep South who goes by the moniker Young Thug, wearing a dress on his album cover and the culture by-and-large is cool with that.”

vigilism.com

Awol Erizku

Born in Ethiopia, Awol Erizku primarily concerns himself with photographing people of color. He takes his visuals a step further by replacing figures in classical works — which for the longest time have been predominantly and unapologetically white — with people of color. As he told i-D last year, this aesthetic was birthed out of a lack of representation: “When I was a kid and I went to museums, I saw a lot of art that didn’t represent me, so I’m trying to bring what I find valuable.” Last month, he collaborated with Beyoncé on her much-talked-about photo series I Have Three Hearts, which revealed her second pregnancy. The shoot borrows from both Renaissance iconography and African mythology, mixing two contrasting cultures to create an intriguing gumbo. Water is also a recurring theme in the photo series. Erizku captures Beyoncé twirling around at the bottom of a pool, like the African spirit Mami Wata, a divine mermaid-like figure. While in the next set of images, the singer sits with a veil covering her face, like the Virgin Mary. Like Erizku’s previous projects, the photo series imagines a future in which black people can reconcile their African heritage and Western culture in a harmonious personal history.

awolerizku.tumblr.com

Inyegumena Nosegbe

“I believe that afrofuturism is a state of being; it’s simply thriving, unapologetically, in your blackness,” says Inyegumena Nosegbe, a recent graduate of Parsons’s Communication Design program. During her Parsons years, Nosegbe created Curated Culture, a quarterly art publication that spotlights the overlooked works of past and present black artists. In one edition, the work of Jean-Michael Basquiat is displayed alongside work by contemporary afrofuturist artists. In the same issue, the past is brought into the present through an analysis of 70s ads targeted towards black consumers. Nosegbe’s other projects include Dear White America (trigger warning: graphic scenes), a collection of the crime scene photographs of victims of police brutality. Nosegbe hopes her work sparks action within her audience. “The next step is to develop something that moves us away from talking about improving our lives, to actively putting in the work that will take us there,” she says.

inyegumena.com

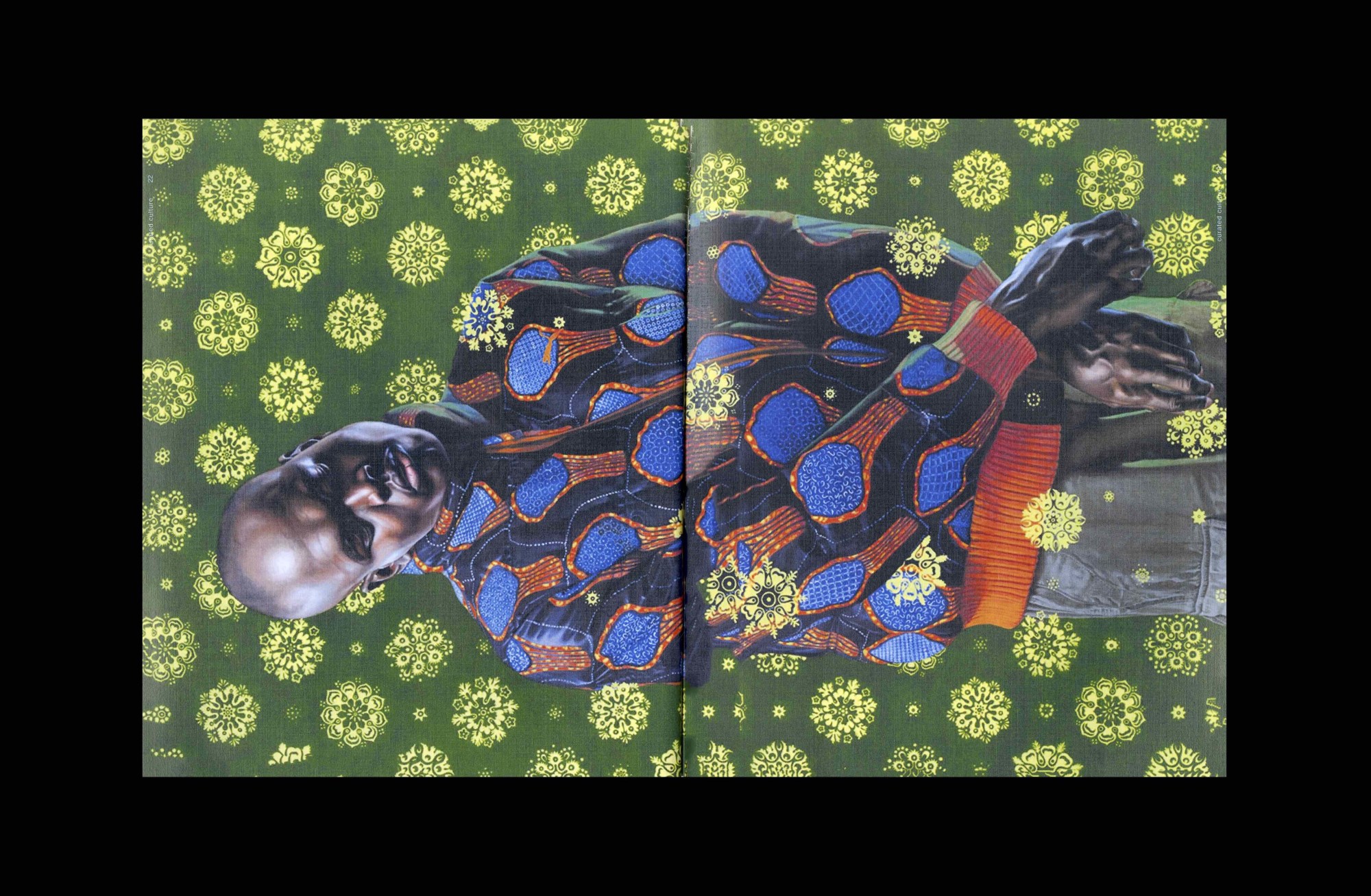

Krista Franklin

Krista Franklin calls her collages a life-long project in disruption. They came about, initially, because she was a “mediocre drawer,” she says. “Out of my frustration I turned to cutting up pictures and reconstructing them,” she says. “Later, it became more intentional and I was using the acts of ‘cutting up,’ deconstruction, and reconstruction in order to decolonize my gaze and the narratives that I’d been indoctrinated with about myself, my community, and my ancestry as an African-American/black woman.” Franklin, who holds an MFA from Columbia College Chicago, first engaged with afrofuturism in the late 90s through a LISTSERV. “A modest number of African diaspora writers, critics, and cultural producers congregated online to discuss and work to define what the term encompassed and included,” says Franklin. “Some of the individuals on that LISTSERV were Alondra Nelson, Tricia Rose, Nalo Hopkinson, Paul D. Miller (aka DJ Spooky), and Greg Tate.” She cites people who may not even know/have known of afrofuturism as major points of inspiration: Aaliyah, Pharrell Williams, Timbaland, Missy Elliott, and Harriet Tubman. “No one ever refers to [Tubman] as an Afrofuturist,” says Franklin, “But she was probably one of the first examples. I mean, she led folks to a future freedom following a star in the sky, and using the technology of a gun.”

kristafranklin.com

Martine Syms

Los Angeles-based conceptual artist Martine Syms is perhaps best known for her 2013 piece “The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto.” A poetic statement written for “whomever will join me in the future of black imagination,” it outlines the purpose and meaning of afrofuturism by waving away concerns with aliens, flying cars, and time travel and forcing the reader to take accountability for the future. Its central question is: “Earth is all we have. What will we do with it?” One of Syms’s other most poignant pieces is the website ReadingTrayvonMartin.com. Described by the artist as a “personal bibliography,” the site is a collection of all the essays, articles, and law documents that Syms read and bookmarked related to the Trayvon Martin murder case. As you scroll through the links, a black hoodie, a can of Arizona tea, and a bag of skittles sit in the center of the screen. The website conveys not only the all-consuming, sometimes confusing, wave of media attention the tragic murder received, but also the personal obsession over facts and news coverage that our 24/7 digital age can foster. As technology (Twitter and the cellphone tapings of police shootings, for example) continues to affect the fast-changing landscape of Black politics, creating an archive of this future-in-progress is a big deal.

martinesyms.com

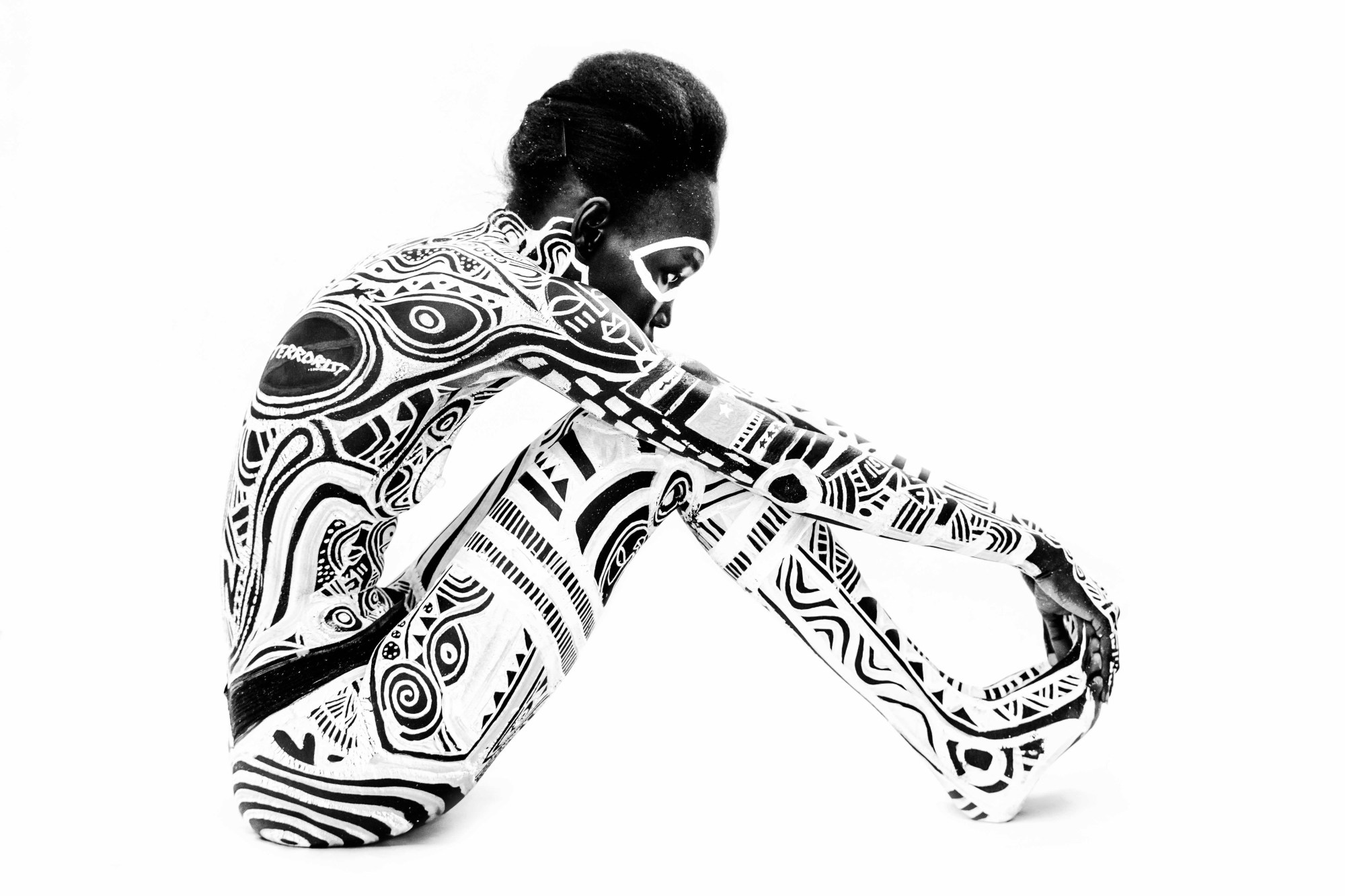

Laolu Senbanjo

Laolu Senbanjo’s intricate designs employ the same spiraled motifs used by the Yoruba people during religious rituals. (The Yoruba have a rich West African history dating all the way back to the 7th century BCE.) At first, his Christian Nigerian parents called the traditional drawings “demonic,” Senbanjo remembers. “There are a lot of neocolonial problems with Yoruba mythology,” he explains. “We took the [Christian] religion from Britain, but not the technology, unfortunately. In school, they would teach us about Greek mythology, but they would not teach Yoruba mythology. Thankfully, my grandmother was very adamant about teaching me.” When he moved to Brooklyn, Senbanjo discovered a welcoming, supportive audience for his art. He collaborated with Nike on pair of special edition Air Max sneakers and was recently called on by Beyoncé. Remember the chalk-white body paint in the “Sorry” music video? That was Senbanjo. “[Beyoncé] is the kind of person that knows exactly what she wants to achieve and looks for people who are in line with the picture she wants to paint,” he says. Seeing Yoruba mythology enter the mainstream brings Senbanjo great joy. Not because Western audiences are appreciating West African culture, but because West Africans are now appreciating West African culture. “Nigerians are embracing this part of our culture that has long been buried,” he says, audibly beaming.

laolu.nyc

Credits

Text André-Naquian Wheeler

Images courtesy of the artists