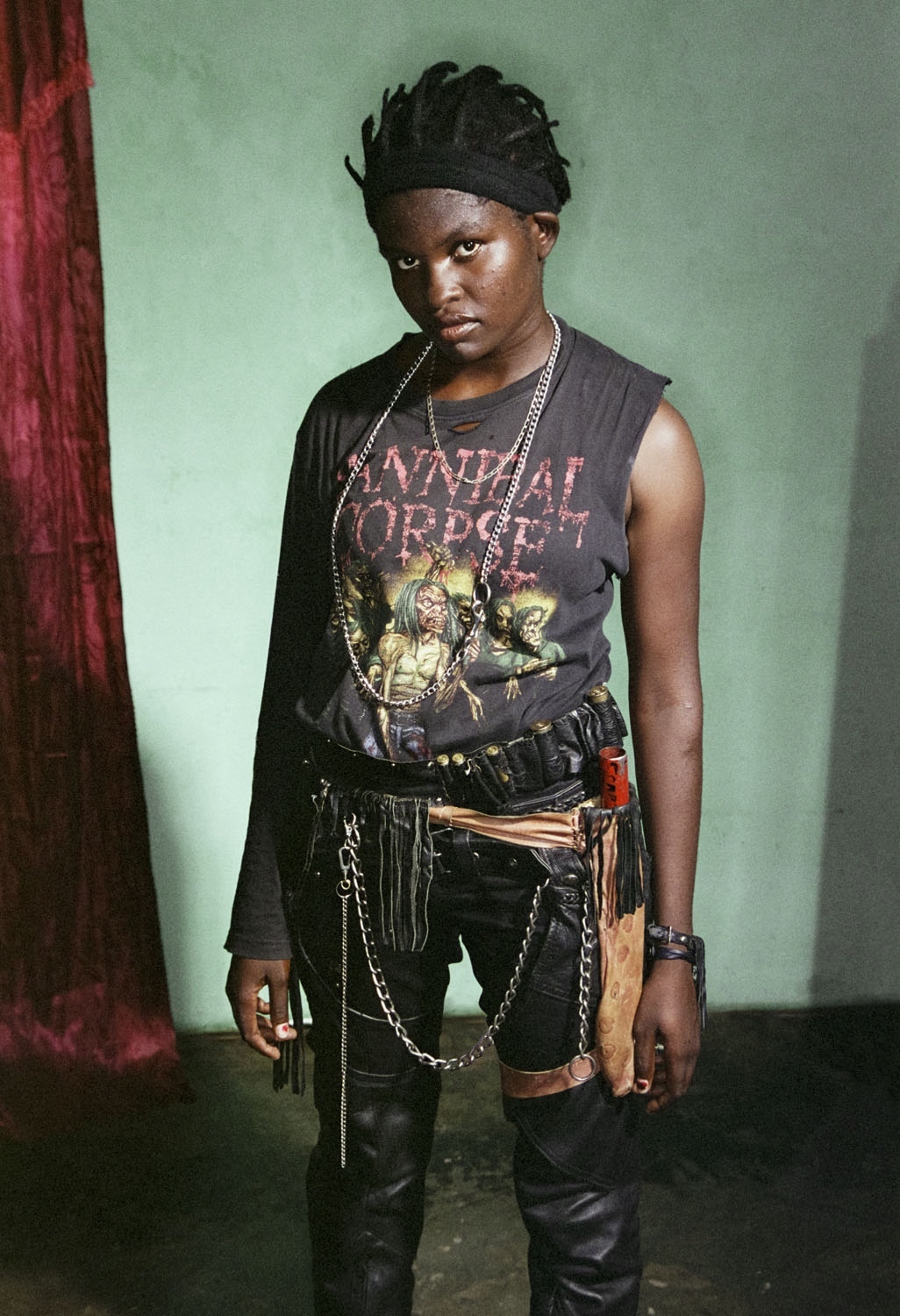

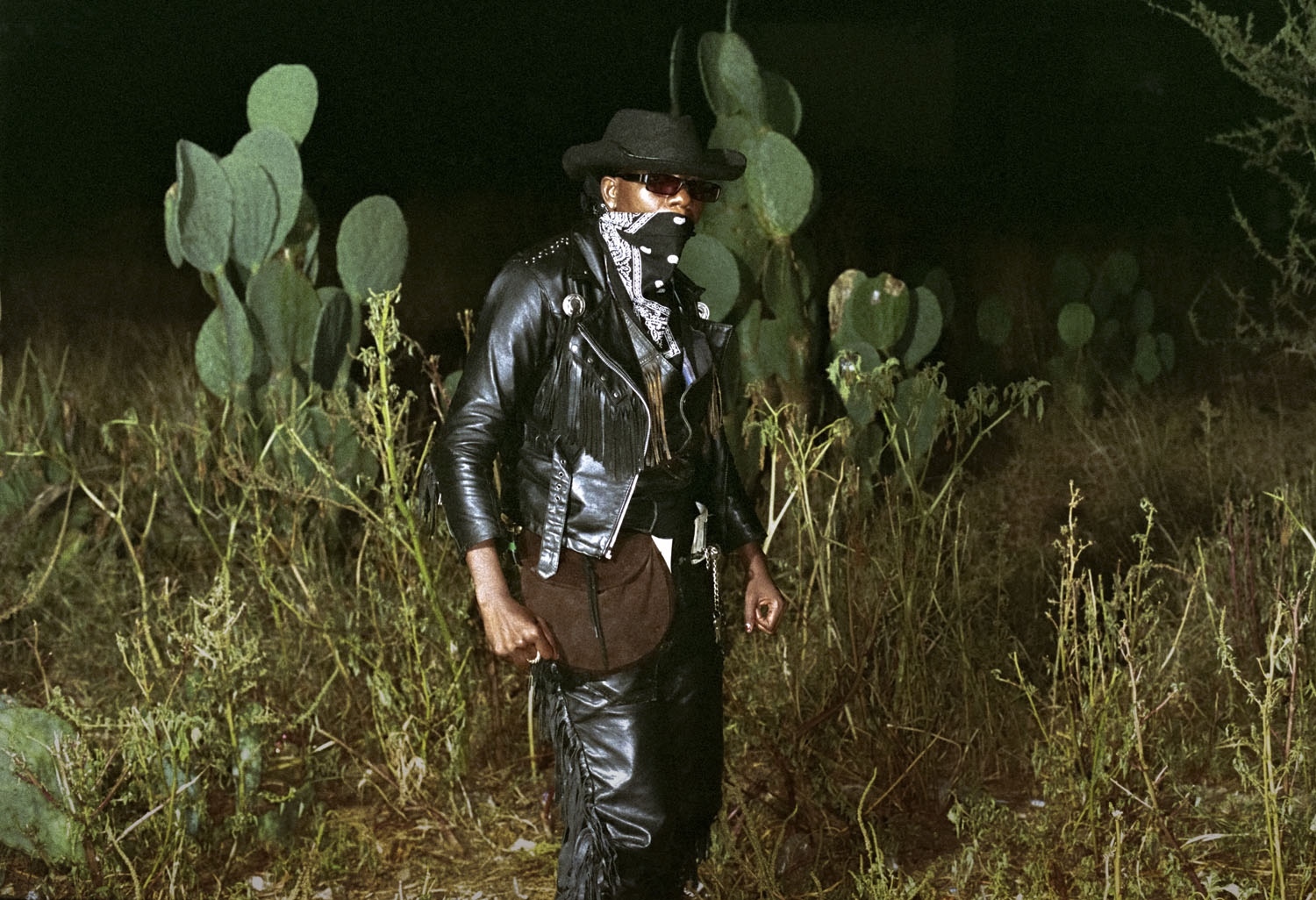

It started at a rock concert in Botswana in 2010: South African photographer Paul Shiakallis noticed a group of black men wearing Mad Max-esque cowboy outfits. Heavy metal T-shirts, studded leather jackets and pants, boots with spurs, and cowboy hats. “I thought they were just dressing up for the hell of it,” Paul recalls. But, at a concert a few years later, he encountered them again—and this time, there were women. “I was instantly attracted to them,” he says. “They were menacing, raucous and very unladylike.” By now, the media had already latched onto the country’s metalheads, known as the “Marok” in the Tswana language, broadcasting bizarre images of African men dressed in post-apocalyptic Hells Angels attire. But, Paul wondered, where were the captivating women he had seen?

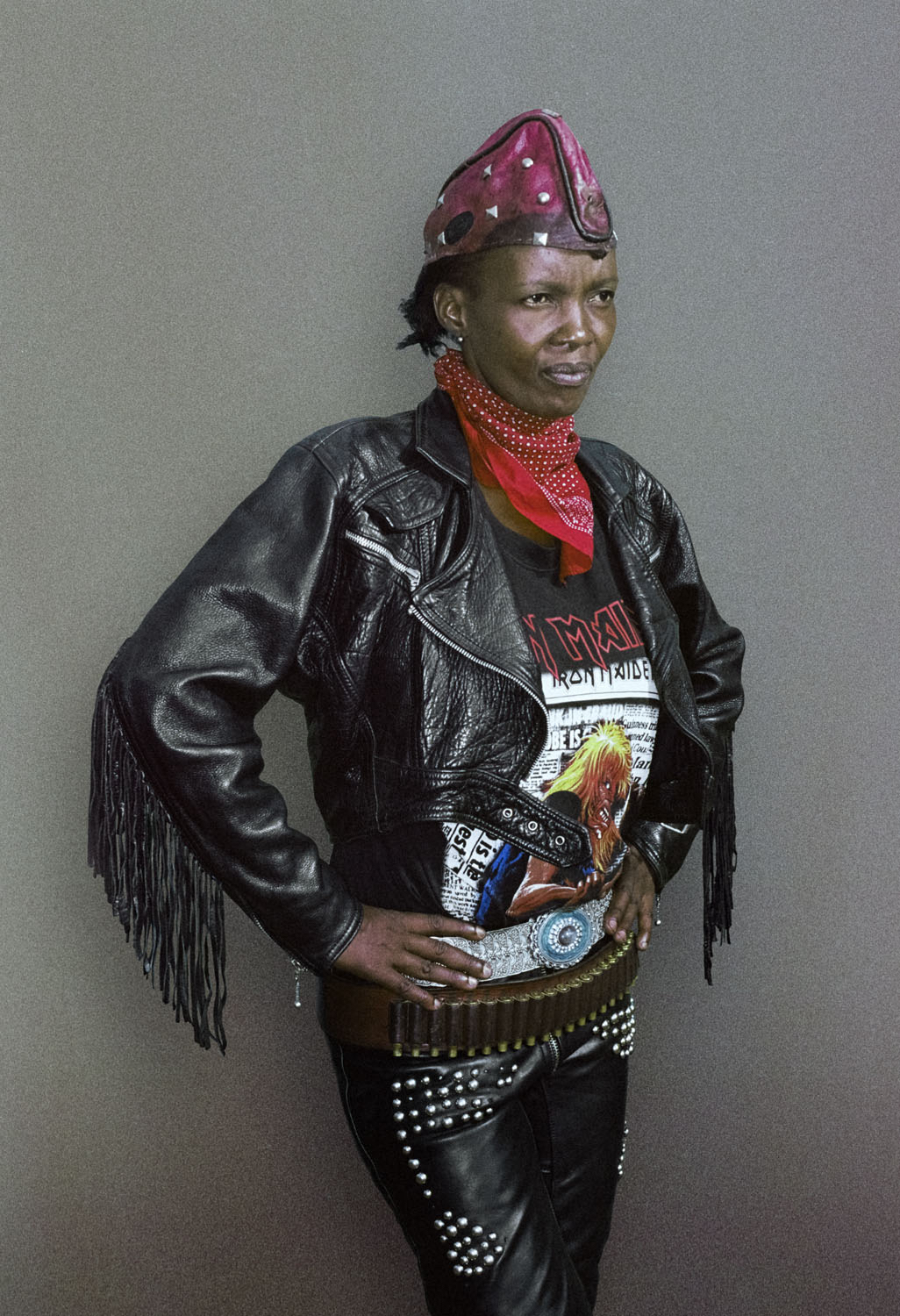

So Paul set out to tell their stories, which, in addition to challenging people’s perceptions of modern African culture, buck gender roles in Botswana. Women there are expected to be polite and submissive. “For a woman to dress up in full black-leather regalia, give herself a vulgar nickname, drink heavily in public and scream and perform to heavy metal music is outright defiance against her man and what society expects from her,” Paul explains. Many of these women are homemakers, though, which makes Paul’s series, Leathered Skins, Unchained Hearts, even more surreal, and also, more intimate. In one of his photographs, for example, a Marok woman dressed in a black leather vest and fringed chaps sits on the bed in her distressed bedroom and holds her naked baby.

For some of the women, who refer to themselves as “Queens,” home is the only place they can dress like this, sharing photos of themselves and their garb on Facebook. The Internet has become the clubhouse for their subculture, and social media its founders’ wall. “I believe girl rockers have a strong voice over a normal society ’cause to be one you got to be outspoken and strong as we are always criticized,” one of the women, nicknamed Phoenix Tonahs Slaughter, told Paul on Facebook. “Only girls who believe in themselves and are not afraid to express themselves can be rockers.”

How did you first hear about the Marok? How did you meet these women?

A friend of mine invited me to a rock concert in Gaborone, Botswana, in 2010. Her father and uncle were organizing it; they were co-incidentally the lead singers of the Nosey Road band, who happened to be the forefathers of rock in Botswana from the early 70s. It was a very small-scale concert of about a 100 people, which ran over a couple days. I noticed a group of black men wearing what I would describe as cowboy outfits. It was this strange combination of black leather, heavy metal T-shirts, spur boots, chains and cowboy hats. I thought they were just dressing up for the hell of it, and was not aware of the actual scene at the time.

Then, in October 2014, that same friend invited me to Gaborone for her wedding. The next day, her uncle had organized a show where her cousin’s band, Skinflint, was the headlining act. There were noticeably more women at this show than I had seen before. Where I’m from, it’s rare to see African metal heads, and even more rare to see African female metal heads. It was an absolutely surreal site. I had never seen a group of women letting go like they did at this concert; it was liberating.

Is this level of self-expression rare among women in Botswana?

Of this particular low-income bracket, yes, very much so. You will notice that the Marok is not a youth subculture; this is because the Tswana are heavily family-oriented and are only really afforded free thought once they are able to leave home and fend for themselves. Religion is quite prominent in Botswana; TV channels are littered by church programs. The patriarchal mindset runs fluidly through the household, culture and religious systems; and women in all scenarios are expected to be submissive; they hardly have a voice.

Is this why you wanted to just photograph just the women?

There had been a few news agencies that had covered the Marok scene before me, but their narratives were about the scene in general. In all the coverage they had, the men, as expected, were at the forefront. They were the face and the voice of the Marok. My plan from the start was to tell the women’s stories. It is much harder to become a rocker as a woman than it is as a man. Men, as heads of the household, can do what they please; women, on the other hand, have to ask permission.

Women from this demographic in Botswana [are expected to be] submissive, polite, lady-like and decent. It was the most surreal thing to see them expressing themselves outside of these expectations. The defiance they express is really important in the fight for women’s basic rights, even if some of the Queens don’t realize it. They have made their mark in history, and will hopefully inspire others to challenge such social inequalities.

Did the parents or husbands ever have a problem with you, as a man, taking the photos?

Yes, every portrait I shot almost never happened. There were a few occasions where shoots were confirmed, but when I called to meet up with the model, I was met with, “Who are you? What do you want with my woman?” It was especially the Queens’ male partners that would thwart the shoots. On one occasion, we were shooting at one Queen’s home; her father, who is a pastor, unexpectedly arrived, and he was not impressed. We offered to stop the shoot, but the Queen was adamant she could convince her father to accept it.

How important is social media to this subculture?

Very important. Some Marok live strictly dual lives—one Facebook profile with their real name and another profile with their self-confessed nickname. It’s not easy for women to just outright tell people they are a Marok. This craving to “come out” is evident on their Facebook profiles; it’s the most amazing thing. They will have pictures of family and kids, birthday messages and inspirational quotes, teddy bears and flowers, and then the next post will be of a skeleton up in flames biting the head off a baby. Then the next post is of them in church clothes, and then, in full leather regalia pulling zaps [giving the middle finger] at the camera.

Who was the most memorable woman you met?

Vicky Sinka, Millie Hans and Phoenix Tonahs Slaughter—all three were over 40, stern and very wise. They had been rockers since their teens and had been dedicated to the scene ever since. I found them the most intriguing because they had fully accepted who they were as rockers and as women. They were headstrong and you could just tell through their demeanor that they were the masters of their own decisions.

Are you a metal fan yourself?

I have always loved old-school heavy metal like AC/DC, Iron Maiden and Black Sabbath, but I got a lot more into it through the Marok. Millie Hans introduced me to Manowar. She invited me over one day after work, and while she was preparing supper for her kids, she handed me a page of handwritten lyrics to Manowar’s song “Battle Hymns.” She had it playing on her TV via a USB stick, and we sang along as if we were at a Carols by Candlelight. It was just so surreal, and so warming.

Credits

Text Zio Baritaux

Photography Paul Shiakallis.

Top to bottom: Millie Hans; Debbie Baone Superpower; Queen Bone; Bonolo; Vicky Sinka; Bontle Sodah Ramotsietsane; Katie Dekesu; Sierra.