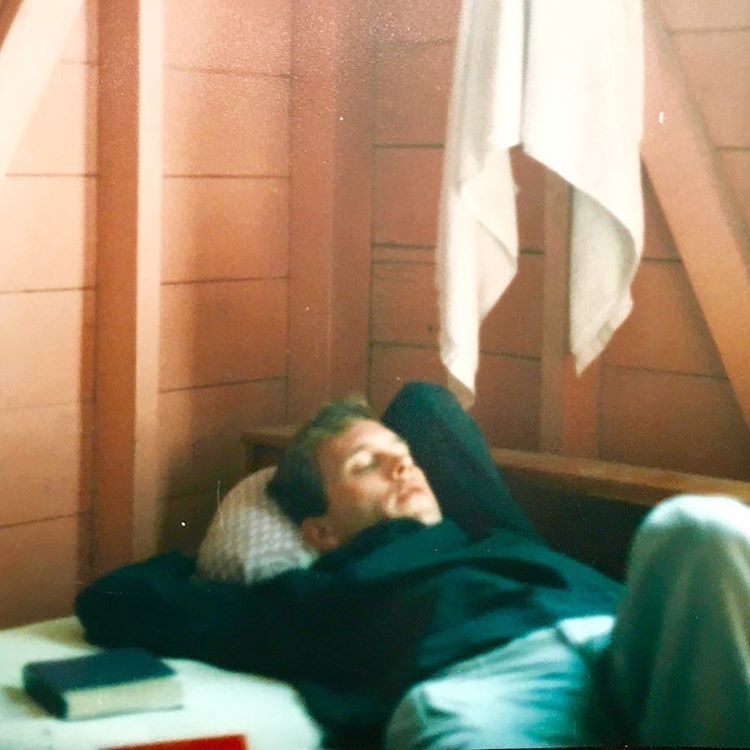

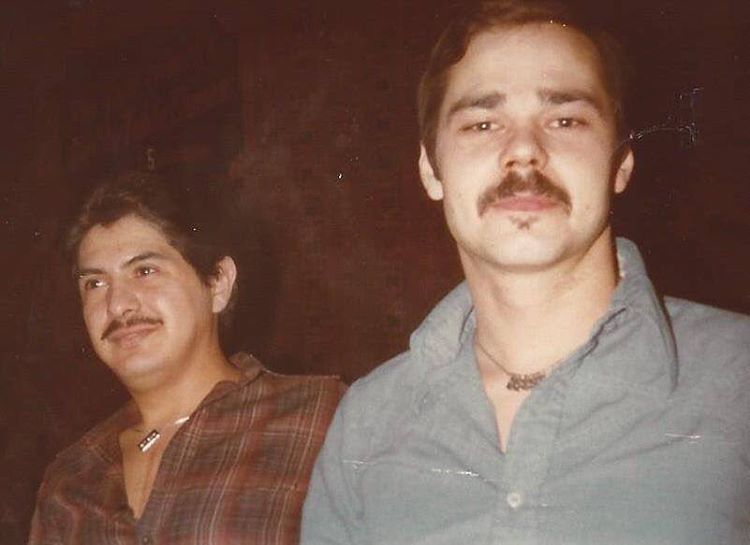

Barb’s on a motorcycle, grinning with her head flung back. Andy, in a cowboy hat, is perched on a sand dune with a cold beer. Anselmo is suited up with his partner, George Michael. The AIDS Memorial isn’t like most Instagram accounts; scrolling isn’t mindless and you don’t envy the lives of others.

The account shares the memories of those killed by AIDS one photograph at a time. Run anonymously by a guy called Stuart who lives in Scotland, it’s snowballed fast, with lovers, friends, nephews, and daughters coming forward to share eulogies of those lost.

There are eulogies for heart-stoppingly beautiful male models, actors, and marriage guidance counsellors — for everyone. Sometimes, the messages are fond, like “Nurses always threatened to throw me out because we were laughing so much we disturbed other patients!” But often, they’re honestly blunt; under a picture of a bunch of mates in a club it just says: “How happy we were before the plague.”

With each scroll, you learn details of lives you might never hear about. Like Mary Rathbun aka “Brownie Mary,” a pensioner who snuck homemade hash cakes to San Francisco AIDS wards for patients who’d lost their appetites. But even with stories of mischievous resistance, there’s little uplifting about the relentlessness of an illness that has killed so many people.

We chatted to Steve about archiving memories, growing up gay in the 1980s, and keeping hope alive when it feels like everything is going to shit.

Read: Flip back through i-D’s 100th issue, devoted to World AIDS Day and activism

Why did you start The AIDS Memorial?

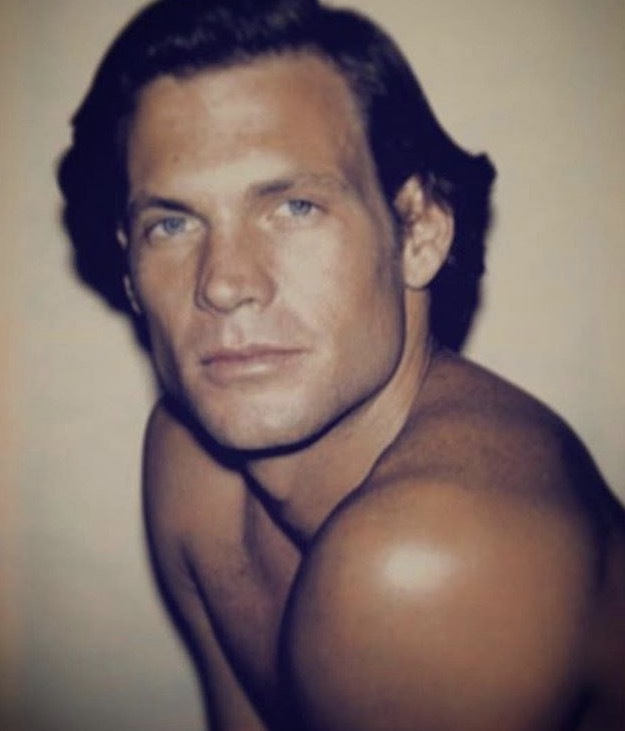

I was always struck by how many talented people passed away and were just forgotten about. People could’ve lived and achieved much more but didn’t get that option. For a long time, lots of people just didn’t want to talk about AIDS, so I started looking for people’s stories. Everyday people. People like Michael Sundin. He was a Blue Peter presenter and a world champion trampolinist but he’s never remembered in those compilations of former Blue Peter presenters, he’s been chopped out. Or Joe Macdonald, the first male supermodel. He was a big art collector and friends with David Hockney. He was one of the first from the fashion world to die of AIDS and it sent shockwaves through the industry. Suddenly models didn’t want to work with gay men anymore.

Was this project something that has been on your mind for a long time before you started it?

I think as a gay man, it’s on your mind from an early age. Whether you want to admit it or not. Growing up in the 1980s when there was so much stigma and hatred surrounding the gay community and anybody dying from AIDS, I tried to block it out.

One of my relatives worked in an AIDS ward, and always banged on to us about wearing a condom. That was odd to hear because my family was Catholic and didn’t talk about sex. But she saw that HIV/AIDS was a death sentence, and that it didn’t just affect gay people. She didn’t think there were gay people in our family!

Hearing those stories, and seeing those terrifying AIDS adverts on the television, and people like Freddie Mercury and Rock Hudson dying, I had this grim realization that I had all this to look forward to when I got older.

Using Instagram seems to be a successful way of making remembering people an everyday act, and reaching people who might not have been exposed to AIDS history.

Someone messaged me saying “Can you slow down with these obituaries? There’s too many of them, it’s really depressing.” And well, I don’t really care, because what about the people that died every single day in the 80s and 90s? They just died and died and died. That was awful. I don’t care if it’s too much for you to bear. The AIDS Memorial isn’t here to make somebody feel good about themselves. It’s not there for it to be easy. People that died of AIDS were ignored at the time, we can’t carry on ignoring them now.

Where do you collect the stories from?

People just started sending me photographs of their their brothers, their sisters, their uncles. I’ve been posting more about everyday people. Share a photograph of Freddie Mercury and suddenly the likes go through the roof. Compared to a guy from Texas, say. People can be a wee bit superficial when it comes to what pulls at their heart.

You say “it’s not here to be easy.” In the age of Trump, It feels like we’re going to have to get better at dealing with difficulty over the next few years. How do you stay hopeful within a political climate that demonizes difference?

I think people need to get over themselves. People say they’re up against it now, but we’ve been up against harder times. Look at what people had to fight through in the era of Reagan and Thatcher, in a society that didn’t accept gay people. Or what organizations like ACT UP — AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, a direct action group — did. They were out there fighting against the grain as gay men and women.

Maybe I’m less sympathetic to people’s complaining, but I think we had it a lot harder back then. They fought and fought and fought. I think we’d be in a worst state today if it wasn’t for them.

Read: You’re HIV positive. Now what?

Do you think there is a way of continuing to fight without burning out?

It’s different if you’re dying and you’ve no other option. I look back now and think “I can’t believe I was so detached from it.” I was young and immature, and just didn’t want to think about what was happening. But a lot of strong people fought because they had nothing left to do.

They fought for access to new drugs, medical attention without insurance, and to get looked after when they’d been put out of their houses. Those people are heroes, and there isn’t enough said about them. There wouldn’t be PrEP (drugs taken before sex to reduce the risk of contracting HIV) or antiretroviral (drugs taken to manage HIV) if it wasn’t for them.

Which films or books would you recommend to younger generations interested in learning more what was happening during the AIDS epidemic of the 80s and 90s?

There are lots of good documentaries. Start with How To Survive A Plague, which is on YouTube. And there’s a BBC Horizon episode, 1982-1983, Killer in the Village about Greenwich Village.

Do you have plans for what you’ll do next with The AIDS Memorial?

I just want more people to hear the stories and remember the people that died. The Memorial gives comfort to those that lost someone. Miss J Alexander sent me a really nice message; he was at Paris Fashion Week and seeing a photo of two of his friends appear on the account suddenly brought back all these memories. Every time a person who died from AIDS appears on a feed, they are remembered and what is remembered lives on.

Read: Meet the fashion student changing the way we look at HIV .

Credits

Text Stevie Mackenzie-Smith