Atong Atem’s work is interested in identity, and the fingerprints colonialism left on her family’s skin. Born in Ethiopia to South Sudanese parents she spent her first years in a Kenya’s Kakuma refugee camp before moving to Australia as a child. Now based in Melbourne her photos explore the experiences of other young immigrants, and how they knit together the different cultures that surround them.

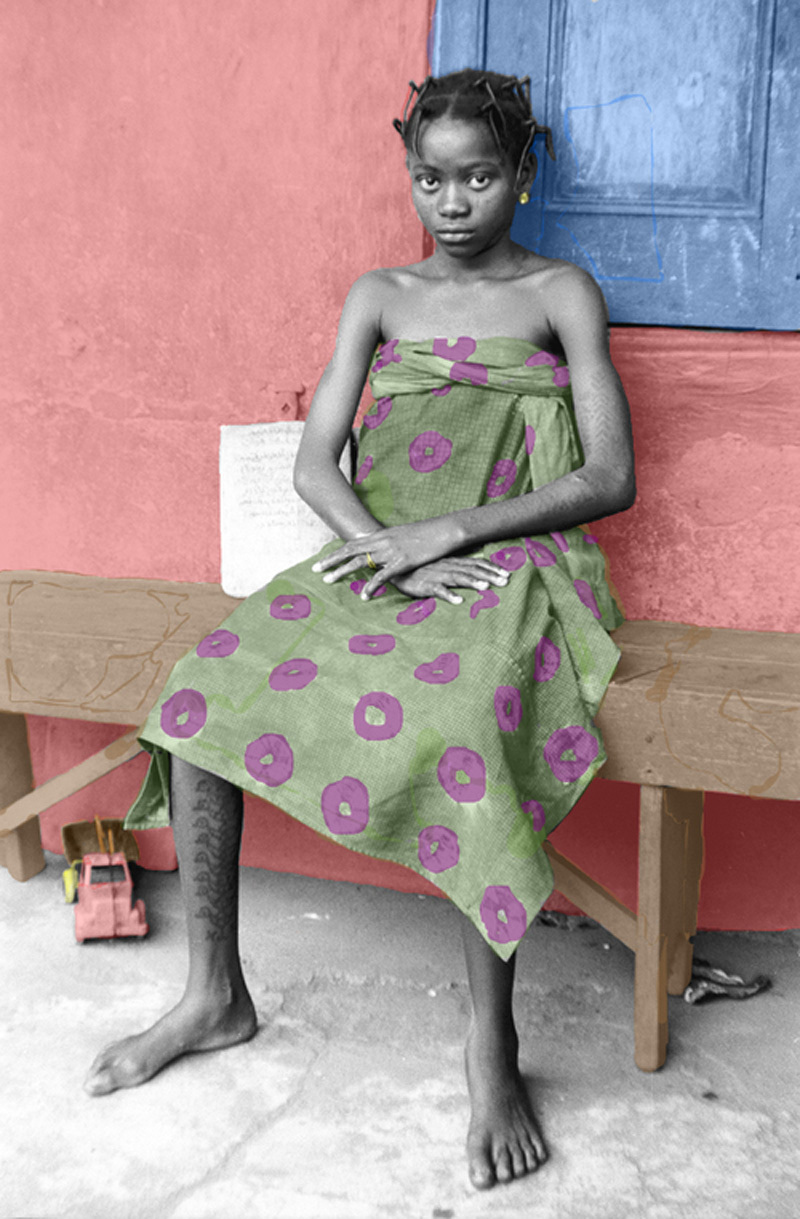

But in her latest work she’s looking to the past, and photography’s role in pillaging communities of their identity. By hand tinting black and white ethnographic photographs from around colonial Africa, she’s meditating on the way we hold and manipulate other people’s histories.

In the original images subjects are posed and photographed like objects; in Atong’s hands they’re given the second thought they missed. But over the course of the project she found herself called to examine her own responsibility as a photographer, and ultimately question how she appropriates and uses the reflections of others.

The last time we spoke to you it was about your series of Third Culture Kids, but your new work is focused on found images. What lead to that shift?

The research I was doing into post-colonial art, colonialism and how that ties into my identity led me to discovering ethnographic photographs of people in the colonies and the introduction of photography into Africa from European colonisers. It was this thing of finding these black and white images and re-appropriating them, of me — being a colonised person — taking photographs made by the colonisers and making my own thing with them. I thought it was interesting for me to connect to that history through art in a very particular way.

Hand colouring photos was a pretty common practice around the turn of the century, but tell me what that process represented to you?

I’ve started leaning towards hand colouring my own work, which feels different. I remember seeing family photo albums where my mum had scribbled out faces with a permanent marker. I said, “You told us not to scribble on things why are you doing it?” And then I found out that this was because when someone has passed away their image is sacred.

These images, in their original form, are very impersonal — the subjects are presented as objects. By reconsidering and reworking them, did you feel you were returning their own narrative?

Yeah I feel like that’s relevant. Also for me it’s interesting because when I take photographs of people I don’t want to recreate that ownership of ethnographic photography. But I’m still appropriating them and their cultures and images — that’s still not my culture and they’re not my people or my family. Even though my motivation for making these photos is completely different to the people who took them there’s still that same ownership happening, which I think is very interesting.

Did interrogating this part of photographic history impact the way you viewed the art form in general?

I was thinking about when I was young and learning about white explorers going to Africa and people being afraid of having their photo taken because they thought it would steal their soul. The people saying this were laughing, but the more I think about history that’s literally what has happened. People’s images have been taken and through that their cultures have been taken.

I find it interesting how powerful photography can be in that way. You can take a photo and make a beautiful image, but you can also take someone’s identity and run the risk of recreating someone’s narrative for your own interest or out of ignorance. It’s this huge puddle of thoughts around ownership and colonialism and taking up space and culture and narratives. For me photography is such a beautiful, simple, neat metaphor to talk about those things.

Previously your work focused on young people, the children of immigrants, the next generation and looking forward. This, by it’s very materials, is anchored in the past. How did that impact your approach to these topics you’ve been exploring for years?

It’s difficult to talk about the future without contextualising myself and my peers in history, which is why it all goes back into colonialism. The way we exist now stems from colonialism and so it felt important to consider the past.

Last year I turned 25, my mum had me at 25. I was thinking about myself as a young person doing my thing and paving my path and imagining mum at this age, wondering what she would have been thinking with this child in the middle of all of the conflict. The logical conclusion is to think about my grandmother and trace colonialism through my blood lines and whatever cellular memories I have of my family’s past.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret

Images Atong Atem