20 years before we first began saying things like “problematic fave,” Great Britain invented the Spice Girls; who, in their own way, invented the chart-topping feminist pop group. They, of course, called it “Girl Power.” Whether or not they invented this — tagging it, so that what once had been politics now felt like bubblegum branding — was unclear. What was clear was that young girls were listening when they said: “We don’t need men to control our lives. We control our lives anyway,” and: “Just because you’ve got a short skirt on and a pair of tits, you can still say what you want to say. We’re still very strong.” No ‘good’ modern feminist pop star would identify Margaret Thatcher as someone to emulate; but to a great many preteen and pre-preteen fans, simply a seeing female or feminine viewpoint as worthwhile seemed radical. “Girl Power” was, in some quarters, still oxymoronic. They were manufactured, but their interview responses rarely seemed especially coached. They were, effectively, working-class. “Let’s face it,” critic Roger Ebert once griped, “the Spice Girls could be duplicated by any five women under the age of 30 standing in line at Dunkin’ Donuts,” as if attainability weren’t the whole point of the group.

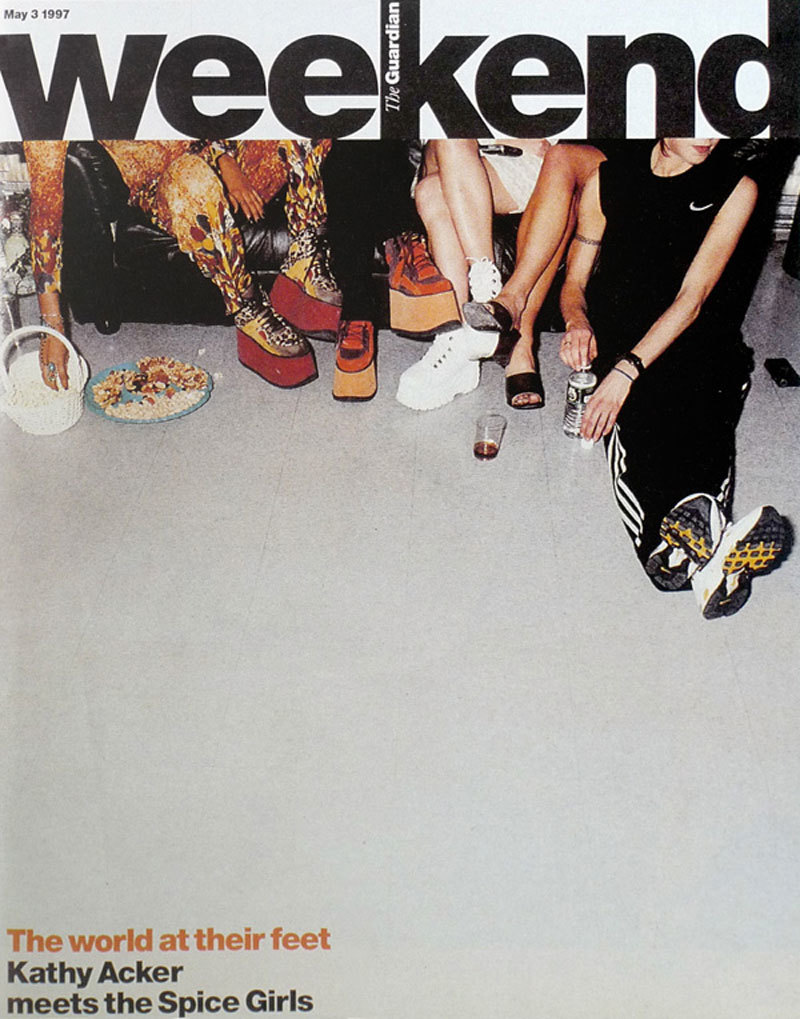

“Feminism!” Mel B exclaims in a screenshot from Spice World: The Movie. She flashes the de rigeur peace sign to show that the statement’s both hip and political; real politicians have done less. “You know what I mean?” Somehow, we do. We understand the spirit of the yell, even if Mel hasn’t yet read the curriculum — and who’s to say that she hasn’t? In May 97, the Guardian sent Kathy Acker, the radical queer writer, playwright, and hell-raiser, to conduct an interview with the Spice Girls shortly before their first televised U.S. performance. I don’t use the word “genius” lightly, but I would use it for Acker, as well as for whoever green-lit this article. Feminism, you know what I mean? The interview’s very first answer is Geri’s, and reads, in full: “Money makes the world what it is today. A world infested with evil. All sorts of wars are going on at the moment. Everyone’s kind of bickering, wanting to better themselves because their next-door neighbor’s got a better lawn. That kind of thing.”

The fact that this remains as true today as it was 20 years ago means less that Geri’s a seer, and more that humanity’s barely evolved. Still: it’s solemn, astute, fairly serious. It is not, in other words, what you’d expect from the sexiest Spice Girl. Knowing Kathy Acker’s prompt was: “If paradise existed, what would it look like?” makes this answer yet more odd and sinister, since it implies that Ginger Spice is either incapable of imagining paradise, or that she thinks that to do so would be a distraction; a waste of time better spent contemplating horror. Like I said about Lindsay — albeit more seriously — she’s like Sylvia Plath in “diaphanous yellow bell-bottoms and top,” as bright as a Ginger lampshade. She’s a micro-mini-skirted Sartre. “Philosophical Spice” would not make quite as cute a nom de pseud: but these are the ideas that Acker brings out in them.

“I can’t keep up with these Girls,” she writes, after spending an afternoon in their company. She is by turns exhausted and exhilarated by their chatter. Isn’t this always the case with a group of girlfriends, let loose? “My generation, spoon-fed Marx and Hegel, thought we could change the world by altering what was out there — the political and economic configurations, all that seemed to make history. Emotions and personal — especially sexual — relationships were for girls, because girls were unimportant. Feminism changed this landscape; in England, the advent of Margaret Thatcher, sad to say, changed it more. The individual self became more important than the world. To my generation, this signals the rise of selfishness; for the generation of the Spice Girls, self-consideration and self-analysis are political. When the Spices say, ‘We’re five completely separate people,’ they’re talking politically.”

In other words — she takes them utterly seriously. There are moments where she records the duff, dumb things they say (‘”I’d love to go back to the Sixties,’ Emma says in her clear voice. ‘I’d love that. I wouldn’t wear headbands though'”), but quite often, she meets them as equals. It hardly matters that Acker is a brilliant author and they are a girl-band; or if it does matter, then it’s the whole point: “They’re the girls never heard from before this in England; look, there are lots of them; ones who’ve known Thatcherite, post-Thatcherite society and nothing else, and now, thanks to the glory and the strangeness of British rock-pop society, they’ve found a voice. Listen to the voices of those who didn’t go to Oxford or Cambridge, or even to Sussex or to art school…They both are and represent a voice that has too long been repressed.”

Born in NYC in either 1944 or 1948 or 1947, Kathy Acker never felt the need to repress much at all. She died the same year as conducting this interview, leaving an oeuvre as alarming as it was exciting as it was explicit as it was transcendent. I read Blood and Guts in High School maybe ten years after I bought “Wannabe” on cassette tape, and if it did not continue the same work, it certainly fell into some kind of lineage. One of Acker’s early fixations was wanting to be a girl-pirate. Weren’t the Spice Girls, when unchained from their managers and left to mouth off, girl-pirates, too? Didn’t they walk the first few steps of Kathy’s pro-sexual plank? It’s so Acker-perfect that in the story, their manager’s name is “Muff.” It is perfect, too, that the piece has one or two lines of description that verge on lascivious. Somehow, you can forgive Kathy Acker’s objectification more readily than, for instance, a middle-aged man who writes phrases like: “throwback people.” To begin with, Acker admits, “even though I have seen many of their videos and photos, as soon as I’m in front of these women, I am struck by how they look far more remarkable than I had expected.”

“I’m listening to Mel B,” she writes later, dreamily. “But all I can think, at the moment, is how beautiful she is.” It feels good to agree with the author: at eight, and an avid collector of Spice Girls photo-cards, I liked Mel B best for her beauty and, frankly, her cool way with leopard-print; this, and Ginger best for her mouthiness and — in a weird, protosexual manner — her chest. The analysis that Acker has solicited from an unknown, pervy Spice fan (“The brunette is the woman every man wants to date… The blonde is the woman you take home to mother, whereas the redhead is the wild woman, the woman-with-lots-of-evil-powers”) neatly underscores the fact that, for Girls as with regular, lowercase girls, an archetype and a stereotype seldom differ. Feminist Tumblr loves an outtake scene from the Spice World trailer, where the girls are getting ready in a public bathroom. Victoria — who we now know to be smarter and funnier by far than her dour, “Posh” Spice Girl persona — asks: “Is my dress too short?” Consensus is: it isn’t. Rectifying the situation, Victoria hikes the thin slip right up to her ass, and the other girls high-five and nod their approval; “slut-shaming” not having yet been invented, this feels like a radical kind of corrective-rebuttal to anyone stupid enough to think short skirts and “girl power” could not go hand in claw-manicured hand.

“It isn’t only the lads sitting behind babe culture, bless them, who think that babes or beautiful lower and lower-middle class girls are dumb,” Acker outlines in her closing thesis. “It’s also educated women who look down on girls like the Spice Girls, who think that because, for instance, girls like the Spice Girls take their clothes off, there can’t be anything ‘up there.'”

Those very women, I’d guess, are the ones who read this at the time and wondered why anyone ought to be listening to women like this. It’s what makes the very fact of this interview, twenty years later, so wild.

Credits

Text Philippa Snow