Nishinari, the Yakuza-run flophouse of Osaka, has long scared off tourists. But photographer Chloé Jafé is no stranger to places perceived as sketchy. In fact, she seems to be drawn to them like a moth to a flame. “Life can be so robotic and lonely in Tokyo,” Chloé says. “I felt closer to the outcast.”

The crime-ridden neighbourhood is the setting of Chloé’s latest book, How I Met Jiro. Following I give you my life (2020) and Okinawa Mon Amour (2020), the latest release serves as the final chapter of her stunning trilogy highlighting the subversive, seedy sides of the Japanese archipelago. Meticulously handmade in a limited edition and housed within a fabric pouch, the book documents the back alleys of Nishinari, packed with doyas (cheap inns), local haunts, dingy karaoke bars and pachinko joints. Stitching together Nishinari’s fallen — homeless people, labourers, transvestites, retirees, bandits, anarchists, prostitutes and poets — with a finely-calibrated intimacy, Chloé seems to restore the gagged history of a nonsensical and charismatic place. Here, she speaks about shooting Nishinari, making friends and the value of vulnerability.

Hi Chloé! How long has it been since you returned from Japan?

Hi! I came back just before the pandemic started. Surprisingly, it was harder returning to Paris than it was leaving in the first place. I had to find the French “inner-self” I had dropped over 10 years ago. It was a bit of a schizophrenic experience. Of course, the pandemic didn’t help either…

So, Nishinari… What brought you there?

My tattoo artist friend, Horiren, told me about this place. She thought I would like it. In 2018, while I was travelling around Osaka, I decided to pass by Nishinari. It struck me as another Japan, one I hadn’t seen before. I felt connected to the people I met there and felt a need to tell their stories.

What was your reaction to the neighbourhood?

Even though I had the experience of photographing the mafia, it was the first time I felt “unsafe” in Japan. Like, as if something really unexpected could happen. The neighbourhood has its own laws and people there have nothing to lose. With the added factors of alcohol and sometimes drugs, a bad encounter could bring you to a place you really don’t want to be. It’s a pretty dark place…

How did you find subjects and make friends?

I would hang out in the neighbourhood, and let my instincts guide me. A lot of people are [living on] the streets so it’s not too difficult to find human interaction. Of course, creating a good connection is a different story. I would start conversations, try to find things that could connect us. Vulnerability is always key for me. Even when someone didn’t want to talk much, I valued sharing those simple moments, drinking a beer or grabbing some street food. Understandably, a lot of people there are also very defensive, in which case I wouldn’t force anything.

And Jiro? Can you tell me about Jiro?

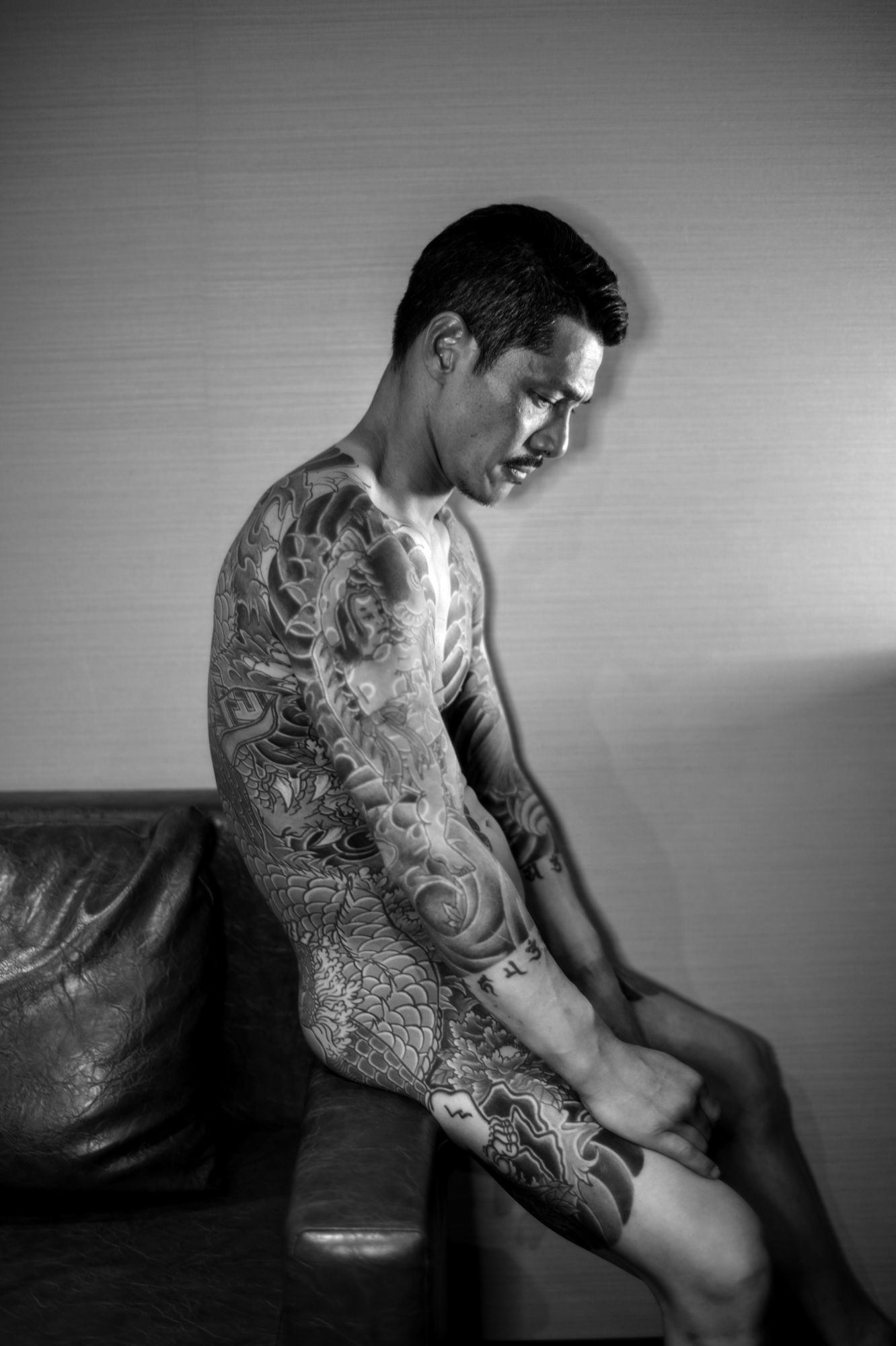

Jiro… Well, he is my very special friend. I can’t find any “title” for him but he is part of my life, and very close to my heart. I met him while walking on the streets of Kamagasaki. I caught a glimpse of his tattoo and mentioned it to him. He grabbed me and took me to a corner, took his T-shirt off, pulled his pants down. Introduction done. Jiro used to work for the “organisation” in the neighbourhood but then decided to retire and opened a yakitori stand (chicken on a stick). From this very first moment, we stuck together. He became my guide and my protector. Even now, there are no two days that pass without us texting.

Sweet! In the book, he’s quoted saying: “Nishinari is a place you eat, a place you drink, a place you have sex… Interesting, funny city.” You seem to have channelled this chaos in an authentic, haphazard way.

I would always start and/or end my day by meeting with Jiro. When I take pictures, there are two components: the information I obtain through my research and the ways I will apprehend it. Across the trilogy of books, the idea of the self has been vital. Authenticity is key, and then you just have to try your luck. I wasn’t sure what I was doing most of the time and just let the night, day or whoever came my way guide me. These are the most precious moments to me. The spontaneous ones.

Have there been any other photobooks on Nishinari?

A few, yes, from different eras. Most show angry homeless men, but it’s not what I saw, nor what I experienced. I wanted to show who else and what else was part of the neighbourhood. I tried to show a different point of view, trying to be more colourful yet stay real.

The vibrancy really comes through.

Coming from Tokyo, meeting these people made me want to make them exist in a more colourful way. When you see how they are outcast from this very tight and organised society, you want to scream!

You always make the most beautiful, intricate books. Why is bookmaking an important part of your practice?

Thank you. I think the photobook is a wonderful medium to disseminate work and explore storytelling. Its possibilities are endless and I like how the book can become an object in and of itself. It can reach a good number of people yet remain intimate. In my opinion, it’s the ultimate step to [making] a work exist.

On reflection, what would you say you’ve learnt from your Japanese adventure?

This seven-year-long adventure turned out to be a big initiatory journey for me. It was mostly fantastic, often lonely, sometimes hard and most definitely memorable. I have learned so much and I don’t know where to start… But if pushed, I guess discipline, patience and respect. All in all, pretty good learning!

‘How I Met Jiro’ by Chloé Jafé is self-published and available here.

Credits

All images courtesy of Chloé Jafé