It is wise, in these times, not to expect artists to live up to the ideals of their work. We know more than we used to about the private lives of our heroes. The reputations of even our greatest idols are not infrequently tainted posthumously, by the reminder or revelation of indiscretions and worse.

Lets be thankful, then, that we had in John Berger, who passed away at 90 years old on January 2, someone of whom we can say: “His life was not the least of his art.”

Berger was of course an astonishingly bright and brilliant mind, a beautiful writer, and a visionary theorist. He changed the way the British public perceive art, and for many was the first person to let them know they might have any perception of art. As well as these achievements, indeed informing them, Berger was a principled man. A lifelong Marxist, his condemnation of the failings of capitalism underpinned the essential compassion with which he approached his work. This compassion is one of the things that defined him as one of the great public intellectual of his age, one who was truly of service to the public and truly interested in it too.

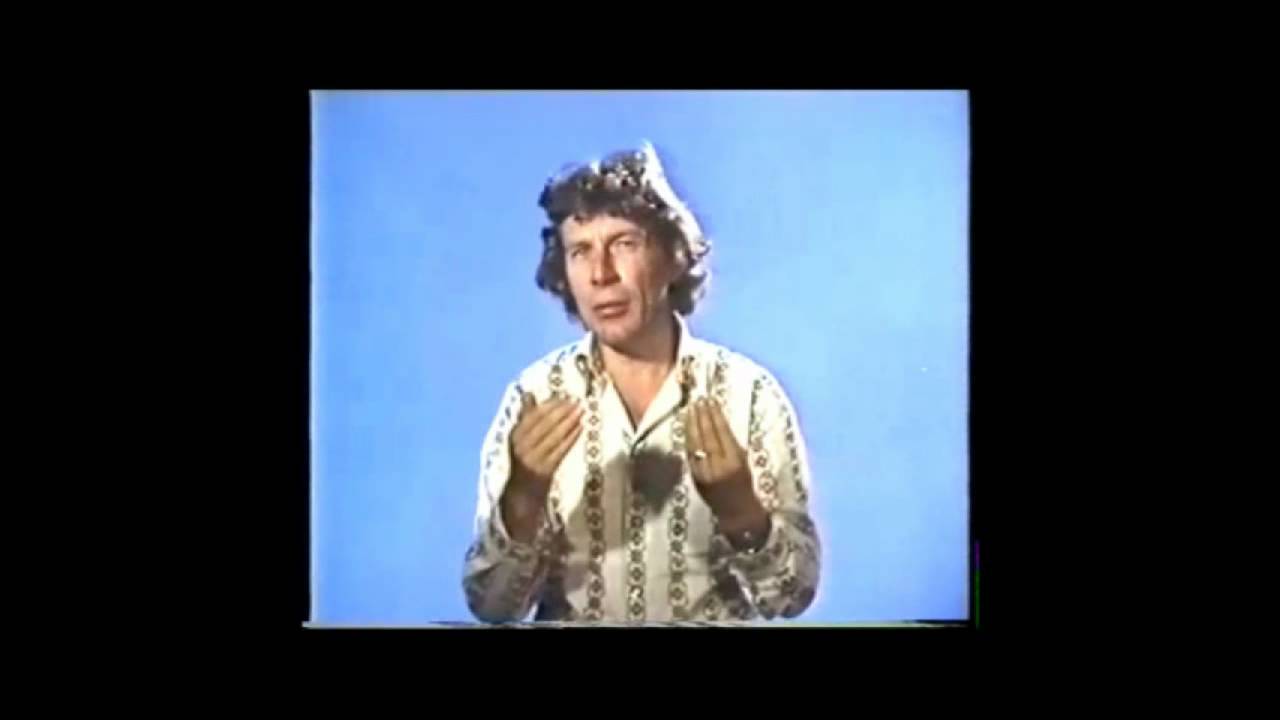

Berger started his career as a painter and teacher, before a series of programs about art on BBC World Service began his life in broadcasting and eventually led to his position as art critic at the New Statesman. He is still best known for the 1972 four-part BBC television series Ways of Seeing he would go on to produce, write, and appear in. On paper Ways of Seeing sounds a doubtful prospect for popular television, but became a gateway for a generation to understand both visual art and cultural theory. The genius of the project, including the resulting book, was in its simplicity. There are few creative pursuits so shrouded in unnecessary mystery as art, and there are fewer still of its critics who do serious work to correct this. Helped by Berger’s gentle and convivial manner, Ways of Seeing managed to invite a whole class and demographic of people into a conversation they had never been part of before.

Ways of Seeing was groundbreaking too for its resistance to the usual limitations of the male art critic. Berger confronted the problems inherent in the representation of women with complete clarity, and elucidated certain ideas that still inform these discussions today. On the female nude, he said “to be naked is to be oneself; to be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself. A nude has to be seen as an object in order to be a nude.”

Berger recognized the inherent farce in pretending that representation of a body could be merely a representation of physical reality, divorced from its context within a sexist culture. He was especially brilliant on this. The first time I came across Berger was reading a quote of his in relation to a critique of selfies. It so perfectly encapsulates how frustrating it is to hear men bully women for being vain, for taking photos of themselves, for presenting themselves. Who after all taught us to face outward like this? Who have we been taught to present to?

Berger’s summation of this hypocrisy, characteristically elegant: “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you own pleasure.” Men cannot condemn us for presenting or enjoying ourselves, so long as they continue to insist on consuming us too.

By way of illustrating his prolific and richly varied career, in the same year as he broke through into mainstream culture with Ways of Seeing, he also won the Booker prize for his novel G. His acceptance speech pointed to the compromised history of the prize money he was the recipient of (the Booker Group’s international trade interests having long since exploited the people of the Caribbean amongst others). He accepted the money, then £5000, keeping half to fund his next book, and donating half to the British faction of the Black Panthers.

1972 also saw the publication of his book A Fortunate Man, a joint project with his frequent collaborator the photographer Jean Mohr. A Fortunate Man was an extraordinary documentary account of a village GP in Gloucestershire, where Berger himself lived for a time. Berger had been treated by Dr John Sassall, who he admired and recognized as an increasingly idiosyncratic example of a particular sort of country doctor. Sassall was a sort of Renaissance figure, whose engagement with his patients, by virtue of his lifelong and intimate relationships with them, was necessarily holistic. He emerges from the book a deeply reflective man, whose medical practice is a starting point for an unanswerable contemplation of human suffering and redemption. Leaving aside the usual standard professionalism, there is no pretense that Sassall is left unharmed by his encounters.

At the end of A Fortunate Man, Berger recognizes the futility of trying to sum a man up by his achievements. “What is the value of a life saved?” he asks. “How does the cure of a serious illness compare in value with one of the better poems of a minor poet?”

It’s a deeply sad book in many ways, an analysis not only of the failures of the human body and spirit, but also the long term effects of social and cultural isolation in deprived rural areas. The doctor’s dedication to his vocation is admiringly described, but there is no easy redemption offered to counter these considerations. Sassall’s depressive episodes seem entirely explicable. He is overcome by “the suffering of his own patients and his own sense of inadequacy,” and so are we reading it.

But although it is a fundamentally solemn piece of work, A Fortunate Man seems to me to sum up a large part of what made John Berger as uniquely good as he was. The unflagging interest he had in other people was elevated to the sacred here, his compassion transforms this from a sociological work to a work of art in its own right. True respect for those who are not like ourselves, true humanity, leads to great art. Throughout his career, his beautiful language enabled this egalitarian spirit too, allowing those of us who hadn’t come through the academy to understand what we otherwise would have been excluded from.

Berger knew that art does not exist on a rarefied plane separate to human life, but is a part of all human life, if we are generous enough to find it there; if we live in a society humane enough to give us time to.

Credits

Text Megan Nolan