She’s whiny, co-dependent, entitled, critical, pretentious, self-conscious yet narcissistic, and she’s gentrifying Brooklyn. She’s a 24-year old Oberlin grad whose parents have just stopped paying her rent. Enter Hannah Horvath, main character of HBO’s Girls and a not-so-thinly-veiled stand-in for her creator, Lena Dunham.

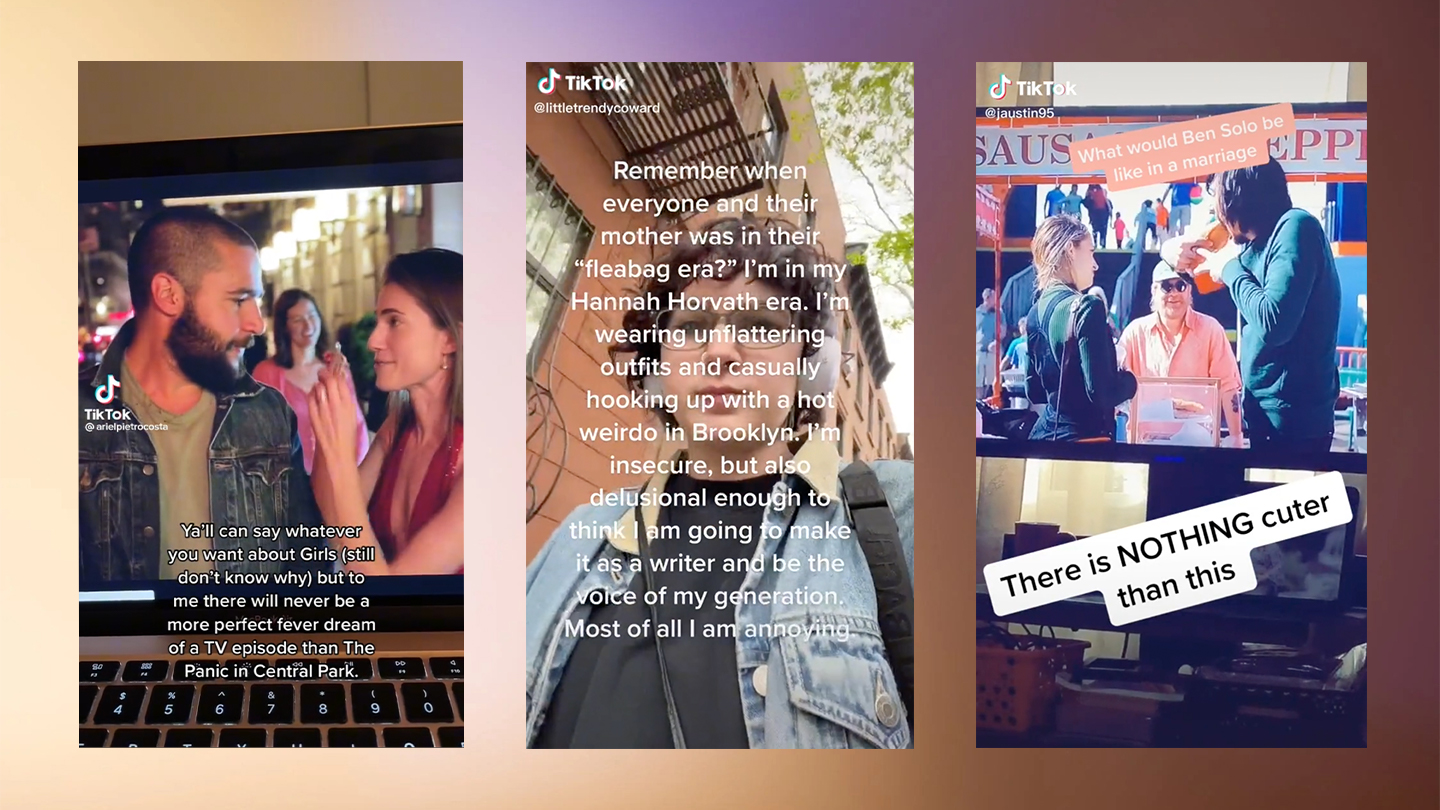

Maybe you’ve seen an uptick in tweets and TikToks, most significantly the Hamptons fight scene and a return to Girls as part of the cultural conversation – not just because of Allison Williams’s role in future cult classic M3GAN. Eleven years after its premiere, it’s not just the perfect time for millennials to revisit the series and look back on their twenties, but for Gen Z to discover the show for the first time, arriving at the same juncture the show explored so cleverly.

Take one TikTok, cut from season two episode “One Man’s Trash”, in which Hannah spends two intimate and emotional days in a luxury brownstone round the corner from the cafe she works in. “I just feel like I’m too smart and too sensitive and too, like, not crazy,” she says, in typical Hannah fashion: both narcissistic and self-reflective, enough smarm to push people away with enough truth to draw them back in. “I just want to feel it all.” The scene has reached a new audience; one that’s likely too young to have experienced the show’s initial rise to popularity, and Lena’s ensuing fall from grace. “She’s just like me fr” “I hope you mean Hannah and not Lena” “Lena is honest” “Its okay to like Girls without shitting on its creator” “SHE’S JUST LIKE ME FR (derogatory)”.

Just like Sex and the City before it, Girls focuses almost exclusively on an insular, white, privileged New York that ignores the multitude of diversities found in the city. Many people only vaguely familiar with the show know it first and foremost for its controversies, but many of its critiques are not only unfair but downright media illiterate. Are we ready to revisit Girls with a critical lens, taking in both the successes and failures of the program as an accurate depiction of its subjects? Recent reboots of SATC and Gossip Girl faced brutal reviews as they tried to embrace a neutered, politically correct tone; with this in mind, Girls’s candour is retrospectively more refreshing.

The titular Girls are largely unlikeable — so much so that they can barely stand each other. Despite this, they aren’t caricatures or villainous, just run-of-the-mill kind of shitty, the kind of shitty that reminds us of our friends or frenemies or even just ourselves. Few pieces of art before, or since, give the kind of genuine literary and emotional complexity to female friendship that Girls allows. The mumblecore sensibilities of the show – paired with the actors’ dry delivery – give it a unique tone that feels closer to reading a diary entry than experiencing entertainment television; one whose simple premise and limited plot leaves us to ruminate only on its subjects.

Girls was criticised for having characters that made viewers uncomfortable, characters that confronted audiences with their very human failings and behaviour. A decade ago, feminist discourse consisted of lewd selfies to prove that feminists were attractive and Mitt Romney’s “binders full of women” scandal. Ten years before Girls, Sex and the City was considered revolutionary for its depiction of women who were single and sexually active. Lena’s task was to depict women that weren’t anything at all but themselves, including all of their complex, off-putting, and flawed ways.

But it is in this discomfort that Girls is at its most valuable: a mirror for self-reflection as we find ourselves squeamish and sensitive to the things we most wish to change about ourselves. One Tik Tok user, revisiting the series for the first time since their early twenties, repeats that she “literally hates” Hannah for being so selfish and finds her scenes unwatchable. Nonetheless, she continues to watch the show. Users comment that they feel the same way about Marnie or Jessa or Shosh – could it be that the characters we find the most irritating are the ones we see the worst of ourselves in?

Many critiques showed a fundamental misunderstanding of the show’s intention, leaving the program with an undeserved reputation that doesn’t factor in its internal self-awareness. Even the title hints at the tenor of Girls: they are not yet women, not yet adults, not yet fully matured, and not yet done discovering who they are. There are many depictions of unsexy, uncomfortable, and unpleasant sex, a very real and underrepresented part of life, shown with an honesty that is supposed to make viewers uncomfortable. Girls is six seasons of grey area, a groundbreaking level of ambiguity for female auteurs whose legacy can be found in the success of media like Milk Fed, Fleabag, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and Normal People. Characters stumble into opportunities through some talent but lots of privilege and dumb luck, and then destroy them because they are insecure or ignorant or entitled: take Adam’s stint on Broadway, Charlie’s app, or Hannah’s hiring and firing at GQ.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

In contrast to its under-appreciated qualities, we have a much more heightened awareness on the role nepotism played in Girls’ creation. The four lead actors, to varying degrees, all qualify: Lena Dunham, the daughter of photographer Laurie Simmons; Zosia Mamet, the daughter of playwright David Mamet; Allison Williams, daughter of news anchor Brian Williams; and Jemima Kirke, whose famous relatives are too numerous to list in a single sentence, speak to. They’ve all gone on to varying levels of success, with Dunham directing the highly-praised 2022 film Sharp Stick, Mamet starring in the HBO dark comedy The Flight Attendant, Kirke starring in Sally Rooney adaptation Conversations with Friends, and Williams co-staring in Jordan Peele’s Get Out in 2017 (and most recently in M3GAN). Despite this, the show’s breakout star was none other than Adam Driver, who went from Broadway bit parts to indie darling and eventually to Star Wars supervillain thanks, in large part, to his role as love interest Adam Sackler on Girls. Looking at his career now, it’s hard to believe he was introduced to the screen as an explosive, sexually-frustrated Brooklynite.

The treatment of race is one of the more complex aspects of Girls, part of a larger question about representation and aesthetics in media. New York is a diverse place, and people of colour are lawyers and actors and artists and baristas and tattoo artists and should not be relegated to play reductive, stereotypical background roles. In doing so, Girls displays the real-life prejudice of their writers, directors, and casting agents. At the same time, social circles of expensive private school grads tend to be overwhelmingly white, even in diverse environments. The suburbanite transplants in the show would be liberal racists with insular social circles, especially considering how exhausting it would be for anyone else to be friends with them. The show has a real, unintentional racism problem while also having a self-awareness about the racism and out-of-touch-ness in its characters (see: Marnie’s awkward, uninvited performance of “Stronger” by Kanye West).

When Hannah breaks up with her boyfriend Sandy, a Black Republican, she cites “political differences” after attempting to lecture him about the racism of the Republican Party, a lecture prompted when he gently said he didn’t like an essay that she wrote about a young woman’s inner monologue, which was “well written” but “nothing happens” (much like Girls itself). Sandy’s response to her lecture, improvised by Donald, lambasts not only Hannah but white-Brooklynite-transplant hipster-culture as a whole, “This always happens. I don’t even know… This whole, like, ‘Oh, I’m a white girl and I moved to New York and I’m having a great time.’ And, ‘Oh, I’ve got a fixed gear bike and I’m gonna date a black guy and we’re gonna go to a dangerous part of town.’ All that bullshit? Like, yeah, I know this. I’ve seen it happen a million times. And then they can’t deal with who I am.” The scene ends with Hannah telling her friends they broke up because, “I can’t be with someone who’s not an ally to gays and women.”

There are plenty of things that make Girls bad: Lena Dunham’s navel-gazing; moments of privilege written as if they were universal; racial ignorance written out of authorial prejudice. There are plenty of things that make Girls great: a well-crafted, meaningful script; honest depictions of the most uncomfortable and understated parts of life; a human complexity granted to its characters. Their failings are too uncomfortably realistic to earn the “she-is-so-me” Gone Girl treatment, their lives are not aspirational nor are they cautionary tales. The criticisms of Girls don’t exist in spite of its progressive aim, nor do its successes in any way “balance out” its failings, but instead characterise the show’s complex relationship with White Feminism. Girls acts as an archive, a document of the very same politics that would come to define the liberal media of the 2010s and still prevail today. Over a decade after its premiere, perhaps the story of creatively-minded but personally selfish girls looking for their place in the world is overdue for a thoughtful re-examination.

It is this recurring sense of honesty that drives Girls, one that Dunham herself sees as its defining trait. In an Instagram post from 2022, she celebrates the tenth anniversary of the premiere of Girls, which she describes as a “maddening, imperfect but always striving-for-honesty show.” In this way, Girls isn’t really about girls or womanhood or New York City, but about its specific characters and writers. One of the show’s greatest successes is that it never tried to speak for any sort of universal experience, instead focusing on the personal. There is no need to relate to the jobs or the apartments of the characters because they are not written as representations but as individuals, allowing audiences to connect foremost with what they are saying and what they are feeling — their anxieties, their ambitions, their feelings of isolation and failure. It is because Girls is so personal that it feels so uniquely relatable; though we are constantly sold female-driven media with the promise of “representation”, the subjects of these movies and TV shows and books must be Women™ before they are people. Girls is certainly political (what media isn’t?), but it was never written to pander to the general public and it never promised to be more than what it was: dialogue-driven character studies about complicated individuals. Perhaps it is only now, a decade on, that we can finally appreciate how boldly feminist that was.