“At a time when there’s so much talk about the end of print, to have people excited to buy a book is a challenge,” Luis Venegas confessed over coffee at the Lower East Side’s Ludlow Hotel, less than an hour before he signed copies of his newest publication at Dashwood Books last night. Of course, he’s not incorrect. It’s difficult for even the world’s most reputable newspapers to generate enthusiasm for five dollar contributions, let alone for an independent publisher to move a 600-page, phonebook-sized monograph off shelves. But if anyone knows how to create buzz for unexpected, informative, inspirational printed works, it’s Venegas — the Madrid-based independent editor and creative director behind titles like Fanzine137, C☆ndy, and EY! Magateen. His newest project, Loewe: Past Present Future, is perhaps his most ambitious, and certainly one of his most exciting.

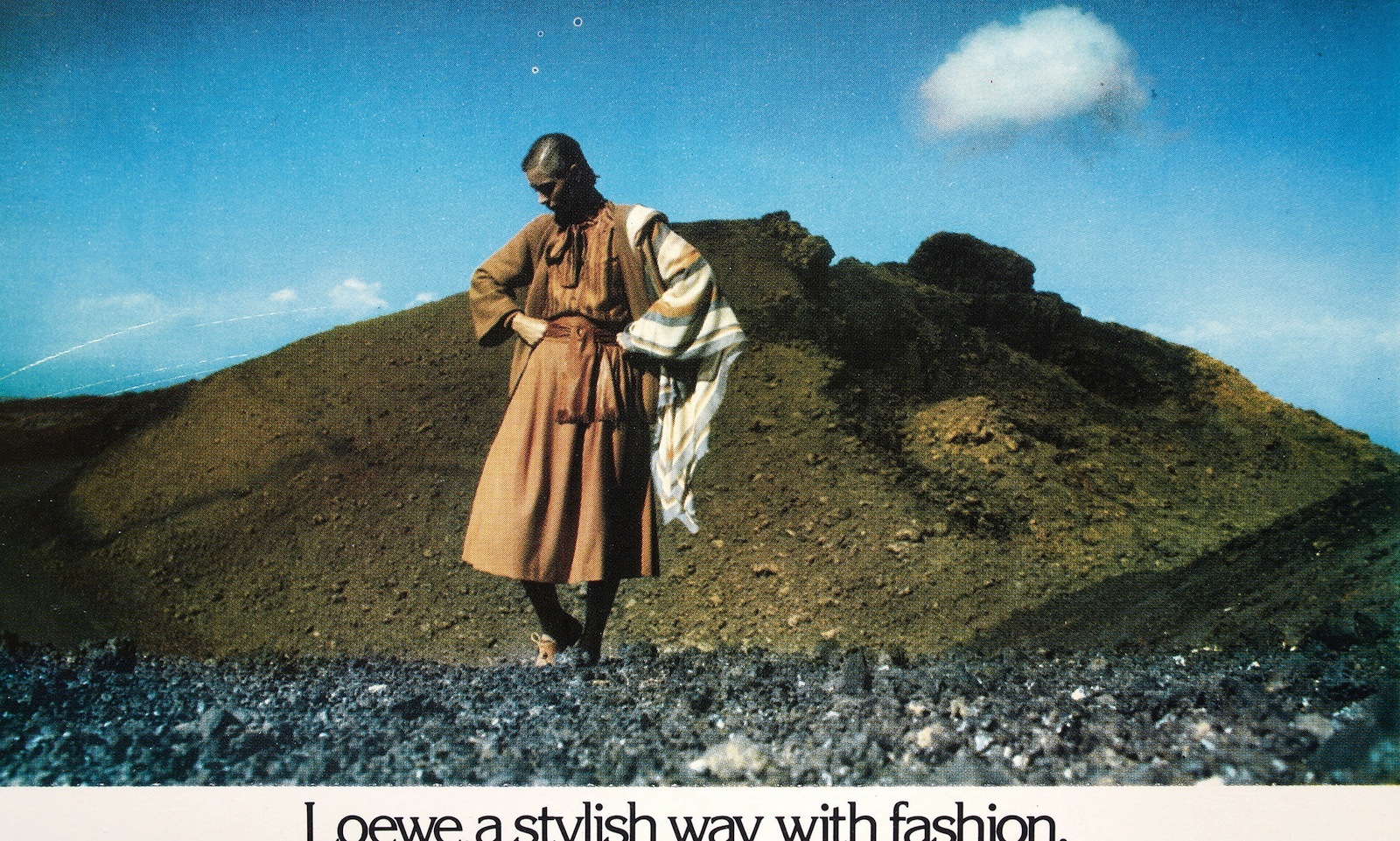

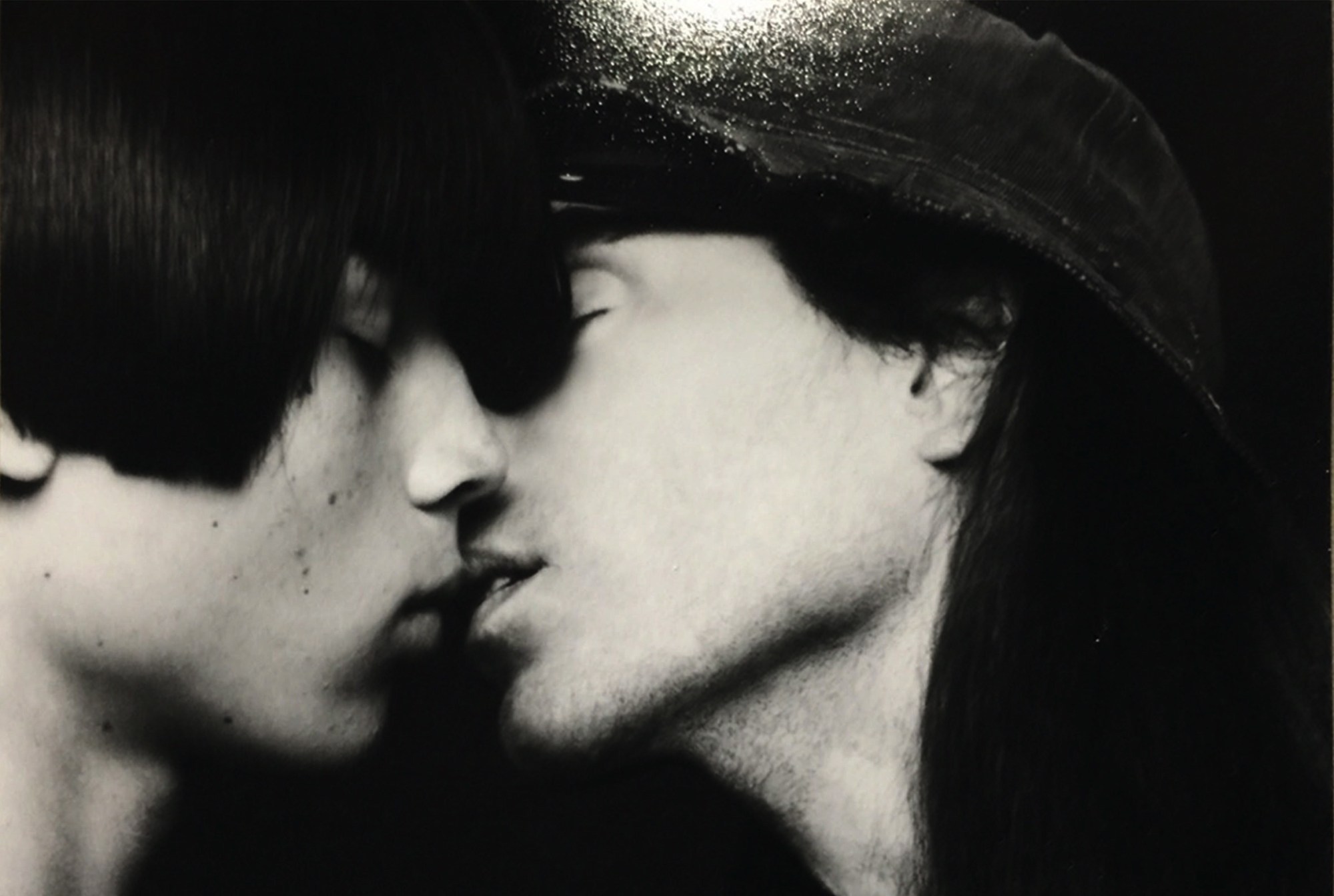

For it, Venegas spent a year and a half inside Loewe’s archives, unearthing hidden treasures from the Spanish brand’s 170 years of history. The book traces its journey from a small leather goods shop to one of the world’s leading luxury houses, currently under the creative direction of Northern Irish wunderkind Jonathan Anderson. But as those familiar with Venegas’s prolific practice would assume, this is anything but a precious linear history of the house’s greatest hits. Loewe: Past Present Future positions Steven Meisel’s iconic campaigns alongside pictures of Venegas’s dog, Perri, draped in Loewe scarves. “I’ve always known Loewe because I grew up in Spain, and there, it’s a brand with real national pride. But at the same time, I’m an outsider, I’m not an employee; I could look at everything with fresher eyes,” Venegas explained. “It was important to me that [the book] was important for Loewe. But it was equally important that I really liked every single little thing inside the book. It was important that it was subjective.”

An hour later, after walking the few blocks from Ludlow to Dashwood, I couldn’t see Venegas or Anderson’s faces — even after I’d made it past the out-the-door line. The cherished basement bookstore was at capacity, packed with an eager crowd of kids excited to discover something new in nearly 200 years of history. Below, we catch up about his relationship with Jonathan and the importance of creative freedom.

You created another book, The Rain in Spain Stays Mainly in the Plain, using J.W. Anderson pieces earlier this year. Obviously they have critical differences, but let’s discuss the connections between the two projects.

I first started working on the Loewe book of April of last year; it’s been a year and a half in the making. For the J.W. Anderson book, I think they asked me in late October. They just started the Workshops in London and wanted me to be the first person to participate. In a way, it was the same thing — I went into the J.W. Anderson archive and did an anthology of the house. But it’s a house that’s five years old; Loewe is 170 years old. The photographs in the J.W. Anderson book happened in three days; I picked out my favorite pieces from the archive and shot everything with friends in a little studio in Madrid. The Loewe book has been very, very different — the process, approach, and the physical object. Both projects, though, have been very free.

How did you select the images you chose?

Every time I start something — a publication or a new project — of course I always consider what’s expected of me, in this case, what Loewe expected from me. But first, I think about what I want to do. And that’s to make something I haven’t seen before, or to do something in a way I haven’t seen it done before. Every time I make something that’s going to be public, especially a book, it has to inform, entertain, and inspire. Those, for me, are the main goals. I was very interested to see what was relevant for Loewe, but also relevant for me in order to have those three things happen. I made the edit myself in a very subjective way; I’d see something, a little box, and ask what it was. ‘Oh that’s nothing, that’s uninteresting.’ And I’d take a closer look and find it to be really something.

Tell me about what else you discovered in the archive. I was reading another interview with Jonathan, and he talked about finding a box to put kids’ teeth in. Was there anything that really surprised you?

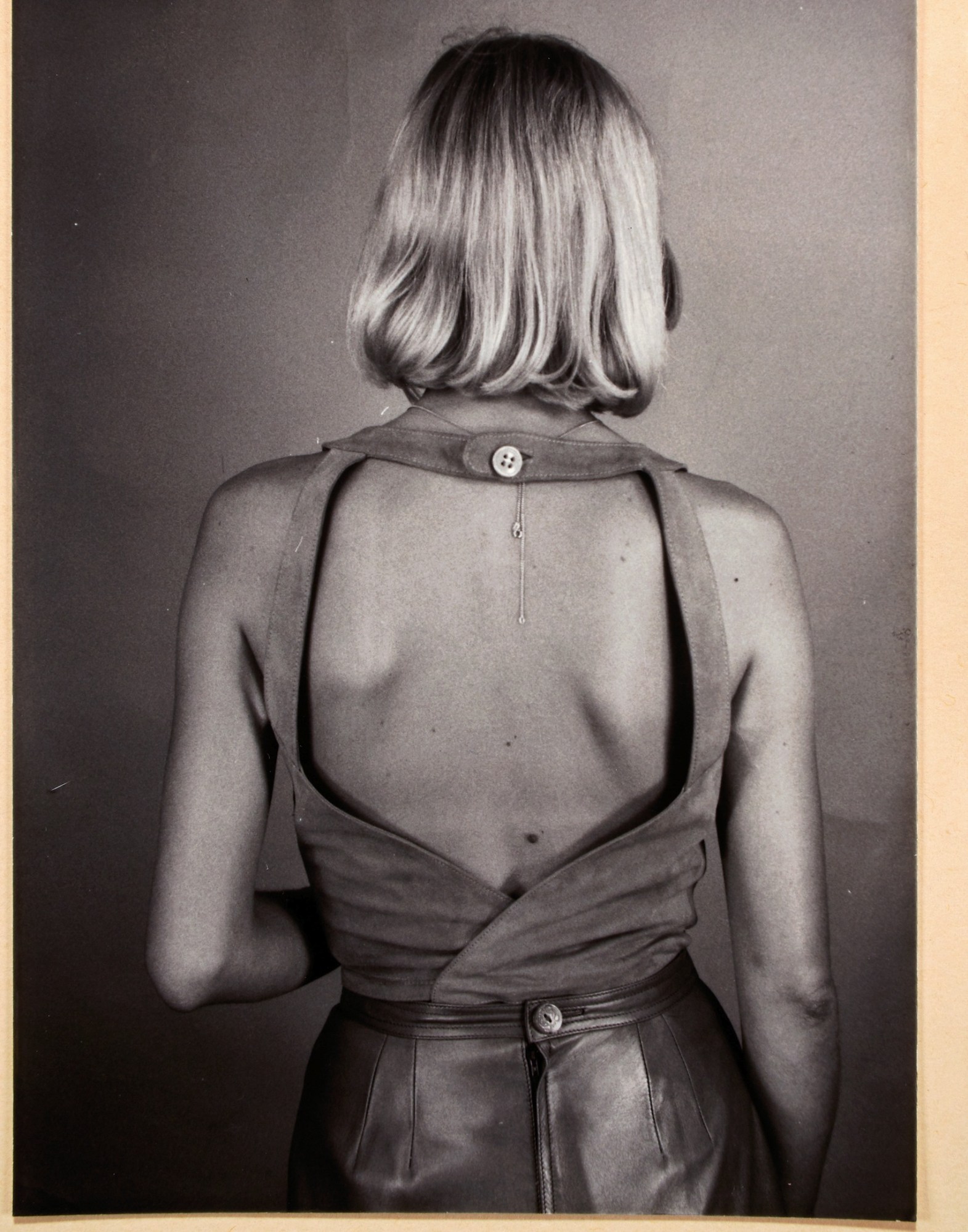

Those photographs with the internal model, definitely. And one thing that I like very much: a photocopy of a drawing of a Karl Lagerfeld design — he used to freelance in the 70s for Loewe. He was working with Chloé at the time, and Loewe had the right to own part of the Chloé collection for shops, before they made pret-a-porter. Armani also used to do things for Loewe. But, what I love especially with that photocopy: there was a little piece of fabric inside a plastic bag — the size of a fingernail. I asked, ‘what is this?’ and they said, ‘it’s a sample of the fabric.’ You could [makes blowing motion from tip of finger] and it’s gone! We had the main Steven Meisel campaigns from right now, but also this tiny little thing that somebody thought it was important to keep. I love that: let’s show the greatest hits, but also the littlest hits.

Being Spanish yourself and having grown up with Loewe, do you feel that there are any elements of the book that draw on that personal connection to the culture?

Yes, because there are also images that aren’t really Loewe, or weren’t shot for Loewe. I put some of my personal photographs in the book, just because I thought they worked well with the narrative. In terms of the emotional link between me, Spain, and Loewe: I shot all the scarves with a naked guy, but also with my dog. It doesn’t matter what happens in 15, 30 years. When I look to this book and I find my dog there, it’ll be really emotional for me. I’m sure of it.

Tell me about the book’s physical form.

It’s a house that’s existed for 170 years; somehow, the object itself had to show that. It has to be something that’s heavy, that has a real presence. But at the same time, I wanted it to be light. I didn’t want it to be like the usual hardcover book; sometimes, when you approach books done by other houses or great artists, there’s a reverence around them — such a reverence that you don’t even want to turn the pages. This was like, yeah, it’s important, but it’s a piece of work. If some student buys it and finds something inspirational, it’s good to have stickers and Post Its available. There are blank pages; I’d love to see someone drawing in them. I preferred this to be an object open to interpretation.

Why did you and Jonathan decide to bring it to New York?

If you can make it here, you can make it anywhere! [Laughs] It’s not only New York, it’s Dashwood Books. Dashwood has been selling my magazines since the beginning. Since I was a child, bookstores have been some of my favorite places in the world; and there are some really great bookstores in New York. I love BookMarc here, and Strand Books. Mike Gallagher used to have a basement, very close to Strand, where he had tons of magazines. The first time I went there, he was picking up all the copies of Italian Vogue he had because Pat McGrath wanted to have the complete collection of all the magazines she’d been involved in. And I want people here in New York to feel it’s an international book — but with a taste of Spain. That was important to me.

Credits

Text Emily Manning